Gardar Eide Einarsson

He may be the most unpopular young artist in Norway, but he’s one of the sharpest critics of macho American youth culture. Is this the land of liberty or what? At first, Gardar Eide Einarsson’s work could be mistaken for the kind of art made by a lot of young, white New York guys these days. There’s plenty of graffiti, references to gangs, skateboarders, the police, a couple flags with dark mottos, and even cameos by radicals like the Unabomber. But the 32-year-old native of Norway proves to be a very different artist from his downtown New York peers. Einarsson’s multimedia productions don’t so much celebrate freedom from authority as cleverly demonstrate the painful limits of transgressive acts. As he prepared for his next show in Oslo and started work on a short film about Lee Harvey Oswald, Einarsson took time out to explain why American myths remain so fascinating.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: You made a rotating neon sign that says JESUS SAVES for Art Basel [in Switzerland] this past summer. What was that referencing?

GARDAR EIDE EINARSSON: It’s based on one of the scenes in Dirty Harry. Clint Eastwood is hiding on this rooftop, staking out a serial killer. There’s this decisive moment where it becomes clear just how evil the bad guy is because he shoots up a JESUS SAVES sign.

CB: You’re from Norway, but so much of your work deals specifically with American culture—usually focused on authority or the outlaw.

GEE: I grew up with a lot of American culture. I was interested in stuff like skateboarding and hardcore music. But growing up in Norway, the whole relationship between the individual and society is very different from what it is in America.

CB: Norway is one of the safest places in the world. Does that make its youth more or less rebellious?

GEE: There’s a very different relationship to individualism. It’s almost frowned upon to be excessively individualistic. People are encouraged to have a social frame of mind. I moved to New York seven years ago. To me, the extent to which this cowboy individualism seemed to be present was shocking. That probably comes out of my having moved here the day before 9/11. In my first year, it was armed guards on the subways and Humvees downtown. I can see those experiences in my work. I was just cataloguing all of the repressive imagery.

CB: There’s a lot of young-white-dude stuff in your work—a very stylish downtown rebellion. But you actually take an underhanded stab at that kind of rebellion. Your graffiti wall texts, for example, look like scrawls. But Total Revolution was made on Adobe Illustrator and traced on the wall.

GEE: That’s definitely something I try to set up. I always have this undercurrent that talks about what it means to use that kind of imagery in an art context. I became interested in art through ’70s conceptual art and an institutional critique. If that critique weren’t there, I think a lot of my work would be stupid.

CB: You also go after very specific outsiders, including the Branch Davidians and the Unabomber.

GEE: I became increasingly attracted to the more extreme, tragic versions of rebellion. Part of the Unabomber’s manifesto is halfway likable, but then there’s a point where it tilts into this tragic character. When I staged the play that was written by the Unabomber, the intention was to show the pathetic quality of expressing these ideas.

CB: You’ve done a number of collaborations with artist Matias Faldbakken, who lives in Norway. You met in art school, right?

GEE: Yeah. Then we started doing a gallery together and a couple of projects in Norway-including Norway’s least favorite public arts piece, which was demolished by the people. [laughs]

CB: What was it exactly?

GEE: It was based on this German fairy tale about Schlaraffenland, which I think in English is called Cockaigne. In this fairy-tale land, nobody has to work, and if you do, you’re punished for it. Laziness is rewarded, and they have mountains of mashed potatoes, and pigs walk around already barbecued. We did a big public art project that tried to turn this public square in Bergen, the second-largest city in Norway, into the fairy tale. People got mad. They destroyed it. Old ladies were stepping on our sculptures. One 80-year-old told us it was the worst thing she had ever seen, which means that it was worse than World War II, when the Germans occupied Norway.

CB: Where do you find the images that you use?

GEE: The Internet. It’s usually through this crazy meta-search thing. I start off on one site, and then link from that to the next one to the next one. I get into the really deep, dark corners of the Internet. There’s some crazy shit out there. It’s also a pretty surefire way to get on some bad lists.

CB: I remember for a long time after 9/11, people were afraid to text certain words. Or you couldn’t say assassination or bomb over the phone because some computer was scanning for it.

GEE: I still have a little fear. I always clean up the desktop on my computer before I cross the border. CB: Do you think you’re a little paranoid?

GEE: I’m getting there. Working with all this stuff makes me have paranoia. I’m making a movie about a conversation between Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby. I had all of this research material and I put it all in one of the desktop folders and hid that folder within another folder before I flew back from Basel. That’s not what you want, right? They open up your desktop and there are 40 documents about the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

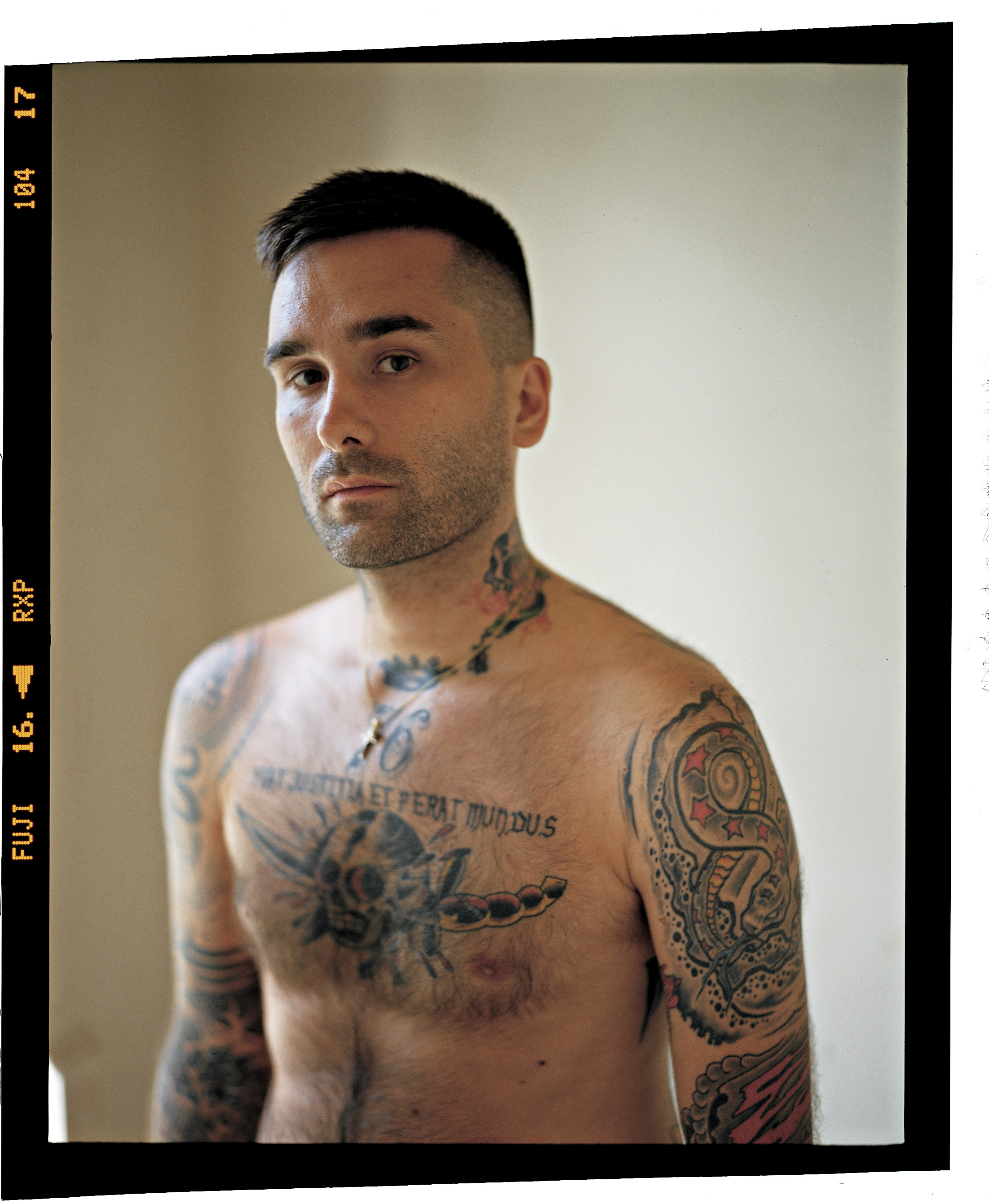

One should never trust someone who has only good tattoos. It’s a really bad sign. You have to have a few bad ones.Gardar Eide Einarsson

CB: What’s the conversation between Ruby and Oswald? There isn’t any evidence that the two met.

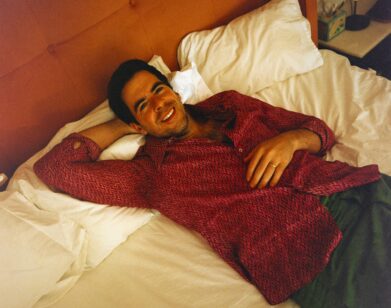

GEE: They recently opened a courthouse safe in Dallas, and there was all this paraphernalia, including the holster that Ruby wore when he shot Oswald. They also found this typed transcript that probably isn’t real. Most people think it’s fake. It’s supposed to be a conversation between Ruby and Oswald in which Ruby orders the hit. I’m making it into this short movie, and Leo Fitzpatrick is playing Oswald.

CB: He’s perfect for Oswald!

GEE: Totally perfect. And my friend Jim Fletcher plays Ruby. I want to shoot it on 8mm, so it has this Zapruder quality. It supposedly takes place in Ruby’s strip club. You can see it having this noir atmosphere, with the two sitting in a red vinyl booth in smoke-filled air.

CB: Do you believe that Jack Ruby ordered the hit?

GEE: No. The transcript seems really cheesy, which is what I like about it. It exists very squarely in this conspiracy theory, but it’s so dramatic.

CB: Like, “Lee Harvey, kill the president!”

GEE: It’s totally like that. And then he says, “Don’t use my name! Just call me Lee!” Then Oswald asks Ruby which person is ordering the hit, and Ruby holds up his palm and says, “Have you ever heard about the black hand of death? The mafia!”

CB: When did you start getting tattoos?

GEE: That’s a long-term project. I got my first one when I was 15. It’s a little one on my back that’s now been incorporated into a much larger one. It’s kind of a crappy tattoo, but one should never trust someone who has only good tattoos. It’s a really bad sign. You have to have a few bad ones.

CB: Otherwise you’re overthinking it. You are working on some new pieces centered around Jackson Pollock, right? He’s perfect for your canon since he’s the ultimate macho American artist.

GEE: He’s hysterically hypermasculine. My image of him has always been this denim-clad, sort of alcoholic, Model T Ford-driving guy. I’m going to keep the show spare, doing remakes of his paintings in ink-jet. Then I’m making a little bronze “scatter” piece on the floor and an ink-jet piece on plywood that is a cutout picture of him as a little boy with a cowboy hat and fake guns.