Father John Misty

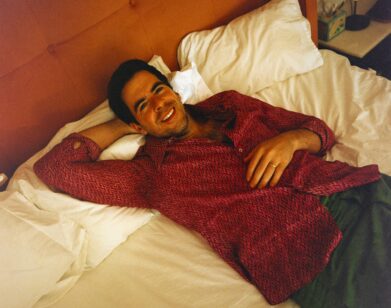

Josh Tillman loves a symbol, loves the variable images and associations they conjure. His first album writing and performing as part of his band Father John Misty, 2012’s Fear Fun, is littered with the iconography of a particular kind of L.A. libertinism. High, low, cliché, sacred, and profane, Tillman makes a menudo of local place names, drug references, and vaguely sinister allusions. But if he shouts out the Hollywood Forever Cemetery or the Chateau Marmont—the Universal CityWalk of Hollywood glamour and debauchery, and a favorite Tillman backdrop—with a weary sort of reverence, it is that of a true Angeleno, which is to say, a transplant from elsewhere.

In the 33-year-old singer-songwriter’s case, elsewhere was suburban Maryland by way of Seattle and a frighteningly religious upbringing (speaking in tongues, casting out the devil), which he escaped to eventually become a drummer in the band Fleet Foxes in 2008. But in 2012, after also releasing seven albums as his soulful solo act, J. Tillman, Tillman quit Foxes, dropped his own name, which had begun to feel like an alter ego, and climbed into a tree on magic mushrooms—maybe not in that order. When he came down, and this now is the traditionally accepted origin story for Father John Misty, Tillman had discovered, to borrow from Borat, his senses of humor.

In this new, plugged-in, psychedelic incarnation, the earlier earnestness of Tillman’s writing exploded into vibrant layers of irony, camp, and sacrilege, as if poured through a postmodernist prism, and expanded into prose (a bizarre, Barthes-ian novel, Mostly Hypothetical Mountains, accompanied Fear Fun, essentially as liner notes). When, on “Funtimes in Babylon,” Tillman-as-Misty sings, “Hollywood, here I come,” it is somehow both sweet and witheringly sarcastic—and wonderfully new, in a found-at-the-Goodwill kind of way. Misty’s early exploits on Fear Fun sound like what might happen if a rhinestone lounge lizard and some Manson girls got marooned on their way to start a commune in the desert. But Tillman processes it through so many layers of meaning and irony that what remains becomes a startlingly intimate communiqué, with reverb. It may be the best album about L.A. in 20 years.

Tillman’s follow up, I Love You, Honeybear (Sub Pop), is 70mm letterbox at the Cinerama Dome to Fear Fun‘s ’70s Kodachrome feel. It is big, elaborate, and sumptuously produced and, a little like Kerouac’s Big Sur, a chaotic, wizened, and burrowing continuation of and reaction to the on-the-road energy and success of its predecessor. As the title suggests, Misty/Tillman is in love, man. But Misty being Misty, his kind of love is … different. So, while he can sing, “People are boring / But you’re something else completely / Damn, let’s take our chances,” it is only after he has promised his betrothed to have “Satanic Christmas Eve,” and tells her he’d like to take her “in the kitchen / Lift up your wedding dress someone was probably murdered in.” Here are the ballads that some polyester Bonnie and Clyde have been waiting to run away to.

But, though he sings wittily and cannily about love and marriage (“How many people rise and think, ‘Oh good, the stranger’s body’s still here / Our arrangement hasn’t changed / Now I’ve got a lifetime to consider all the ways / I grow more disappointing to you as my body warps and fades / And I suspect you feel the same / When I was young I dreamt of a passionate obligation to a roommate’?”), Honeybear is, as all his work has been, principally about Tillman trying to become Tillman—through the panoply of masks he tries on, through the wanton promiscuity, through intoxicants, through failures, and within the crucible of love and marriage (he married filmmaker Emma Elizabeth Tillman in 2013). So even if his stage act sounds like one of Robin Hood’s forgotten merry men, or indeed like the pastor he once aspired to become, the Tillman behind the veils is vividly human—disarmingly candid, funny, cranky, and perhaps unsurprisingly wise on the topic of self-discovery. In January, Tillman called me from L.A. to tell me he’d already moved on (he and Emma now live in New Orleans), and to talk about that mushroom trip, peeling back personas, and the greatest cosmic joke of all.

CHRIS WALLACE: Let’s talk about love. You’ve talked a bit about how, on this album, you’ve gone from the sort of lusty love of Fear Fun into something else, something more—a divine kind of love.

JOSH TILLMAN: I don’t think there’s anything divine happening. I mean, the closer you get to intimacy, the less divine things become. Maybe from a distance, the album is about love, but I think that under closer scrutiny, it’s pretty much about me and my confusion, my lack of clarity. I found myself in this new intimacy, and very quickly you become like a child, and all these traits, like jealousy and neediness, start to manifest. As does this tendency to dehumanize your partner by turning them into, like, a sacred object, deifying them or whatever. I guess a lot of those sacred cows had to die.

WALLACE: It seems to me that there is real tension for you in wanting a sincere, emotionally naked sort of self-expression—who you are and what life feels like to you—and wanting to ironize it, or not take it so seriously. Some of the things you say, about love, about marriage, seem to come out of both sides of your mouth at once. For instance, you got married fairly recently. What are your thoughts on the institution of marriage?

TILLMAN: Well, the institution is irrelevant to me. I give myself the right to make it what I make it. It’s a collaboration between Emma and me. And as far as we’re concerned, we’re the first people ever to have done the thing that we’re doing. Listen to the lyrics in “I Went to the Store One Day.” I’m saying, like, let’s just “put an end to our endless, progressive tendency to scorn provincial concepts.” That’s a prison—you live inside this self-satisfied prison of your intellect and never do anything and never create anything because everything is an institution. For an intellectual, everything is a booby trap, and the only consolation prize is this self-satisfaction that you recognize it. “Holy Shit” is about me waking up from that intellectual dream and saying, like, “Yeah, maybe love is just an institution based on resource scarcity”—these sentiments that sound great and sustained me for a while. But now I’m building this thing with this person, and those ideas just don’t work anymore. They no longer describe the reality as I see it, which is really liberating. And liberation is not typically a trait of institutions. The irony here being that it sounds like I’m intellectualizing all of this.

WALLACE: Right, but you sound a bit freer from the theoretical parentheses around all of these things. Like that cynical old idea that love is a biological trick to seduce the population into reproducing—a seemingly clever take, until you fall in love, and then all the theorizing is complete claptrap.

TILLMAN: Yeah, it’s also bullshit because reproduction is its own thing. Let’s go all the way back to the dawn of man. Why did humans start caring, start providing for one another, forming these bonds that would later on be described as love? It’s because humans, unlike any other mammal on this planet, are completely helpless when they’re born. We have these grotesque, massive brains that are so big that evolution had to make them smaller, just so we could get out of our mother’s birth passage. The price being that we come out completely unprogrammed, with zero innate instructions. We’re immobile for years. We can’t fend for ourselves at all, which means that somebody has to carry us around for a year, two years. We’re completely pathetic. So something has to fill the gap. Talk about love being a trick so that we can propagate. Nature has made it so that we would be extinct without love, without someone. Not in the sense of “love,” because love is a collective project that every generation of humans adds to—a necessary illusion. Love is not a thing that exists out there that you accept; if you don’t make it for yourself, it won’t exist. We’ve become really passive about it as an idea—looking for it, developing this superficial criteria in terms of the kind of love that we want. We approach it like consumers. But it really is something that you have to create. In terms of sex, early on there was this economy where it was, like, women need iron; babies need someone to hold them all the time and give them milk; meat has iron in it; men do nothing innately useful biologically for a baby, so they have to go out and get meat. Anything that they have to offer is external. And out of all of these strictly biological and naturalistic variables, which are cruel and strange and inconvenient, we cobble together something like, “we’re all in this shitty deal together”—so there’s solidarity there. And I think that that solidarity is the spark where love came from. Or something. And talking about this tension in my work, that’s what [the song] “Honeybear” is about, the extent of what love is: “I’m miserable. I can’t control my moods. Most of the time life is grotesque and farcical to me, but you see things the same way, and that decreases my isolation.”

WALLACE: How much does your art feel like it’s personal, and how much do you feel like it’s commentary? Not that those two things can’t coexist.

TILLMAN: They can coexist. And I certainly wouldn’t campaign for anyone else to live like I do. People who are at peace with a lot of these issues wouldn’t need to make music about it. I mean, I’m a person in conflict. And that’s where all of it comes from.

WALLACE: You’ve talked about the sort of expiration date for Father John Misty as a project. And you do seem to already be distancing yourself from the character in Fear Fun, critiquing the lifestyle. And, going back, your sort of famed origin story is about how finding a sense of humor about it kind of unlocked you. So, chicken and egg: Are you having to reinvent yourself for the work, or is the writing a way to push yourself into new domains?

TILLMAN: I don’t know. I could tell you what I’ve said a bazillion times before, and reinforce this narrative and simultaneously undo the reinvention by living in the past.

WALLACE: [laughs] Right. By quoting your former self about reinvention.

TILLMAN: It’s hard because … In all honesty, today I don’t feel like a reinvented person at all. In my music, I’m interested in vitality. And if anything, the name-changing, all of the postmodern metafiction and the pastiche and the intertextuality, all that mumbo-jumbo in the music, that all helps me get closer to the vitality, because I think, on some deep level, I don’t trust myself. On some really, unfortunate, deep level, I think that it’s impossible to be anything other than a fraud in the public eye. So a lot of the talk about reinvention and being particularly harsh about the past is to maybe more and more convince myself that I’m becoming less and less of a fraud, getting closer to something more honest. Bon Iver’s a stage name. St. Vincent. I mean, I don’t really read those guys’ press, but I presume that … Actually, I shouldn’t even bring it up because I don’t even know, and my self-pity would probably rather have me believe that I get more questions about this than other people do. [laughs]

WALLACE: You’ve made your struggle with personae part of your story.

TILLMAN: Absolutely. I did have this realization with the J. Tillman thing—that there was an alter ego there, that [the character represented in the songs] didn’t bear much resemblance to me. And this growing disparity between me and that person made me really interested in the idea of identity. I also read this book called I Am a Strange Loop by Douglas Hofstadter around that time, too, which is all about chaos, mass, identity, and all that jazz—the idea that names are basically just a sequence of phonetic sounds, as arbitrary as that. Father John Misty is—it was—the most patently absurd thing. It came off the top of my head. It had zero significance to me, and that really appealed to me. It appealed to my kind of combative sense of humor to put out such a blatant red herring. On the other hand, it’s a mask. I know that’s a loaded word for people and it implies that I’m lying, but I’m trying to be forthright about the fact that these personas give me a foil. Here’s this bizarre mask. Now I’m going to give you everything about me. I mean, if you listen to this album and think that it’s about some made-up character, then I certainly can’t reach you. But from the first album to this one, I’m getting closer and closer to the beating heart, you know? And, alter egos or personas don’t change, they don’t grow or evolve. They’re like a trademark, they have to stay the same thing in order to maintain their appeal.

WALLACE: Well, that beating heart—selfhood or whatever—and your earnest and chaotic pursuit of it is intriguing. It gives off heat. How did that searching start for you? When you were a kid, did you play characters as a way to better understand who you were?

TILLMAN: I was given such a relentless example of what artifice and dishonesty looked like really early on.

WALLACE: What was that?

TILLMAN: Well, with religion and church. For me, early on, there was always some awareness about this, because I was expected to play a part. I was expected to parrot certain beliefs and to behave in a certain way, to engage in rituals, like Baptism and, later on, speaking in tongues and getting slammed in the spirit and having demons cast out of me—all this stuff that made me sick in my heart, because it just … I was playing a part. Anytime I was doing that, I was playing a part. It just didn’t resonate. And in my poor little brain, I knew that God knew that I was only … that it wasn’t real. And I felt like I was observed all the time. In my private moments, I was being observed. So there was this real conversation, from very early on, about the “real.”

WALLACE: What did you flee to, then? How did you rebel and find comfort?

TILLMAN: It was really with reading. That was my big rebellion. [laughs] “Brackets: laughs bitterly.” [Wallace laughs] It didn’t really take on the sexier characteristics of youthful rebellion. Actually, I don’t really remember much about what was going on in my brain at that time. I have this idea that, at some point, I just held my breath and was like, “I’ll see you in X years when we’re outta here.” That was really my mentality, because I was so paranoid and unsure of how much I could really do other than just survive these insane people with their psychotic ideas.

WALLACE: “They” being your parents?

TILLMAN: I definitely would include them in that.

WALLACE: Was it Pentecostal, your parents’ church?

TILLMAN: It’s a whole pastiche of things. I went to a school that was, yeah.

WALLACE: So your sense of humor, then, was a survival technique?

TILLMAN: Definitely. I mean, anyone could psychoanalyze me. My biggest influences were funny shit. It was when things were funny that I got some oxygen, whether it was The Far Side or Mystery Science Theater 3000 or Monty Python. Stuff like that was how I realized that there were others, so to speak.

WALLACE: More people like you.

TILLMAN: Yeah.

WALLACE: And irony comes in very useful when you hate what you have to obey or perform. When I first became aware of you, you were speaking freely about your self-destruction and nihilism—again, seeming like you were saying it both ways, honestly and taking the piss. You said that, walking around New Orleans, you would see homeless guys drinking behind a dumpster and think to yourself, “I could get down with that. I’m fine with that. That looks good!” And for a lot of people, myself included, that’s fucking terrifying, the bottom falling out like that. But now it totally makes sense that there’s a will to go all the way behind the dumpster if that’s where you need to go to try to survive that.

TILLMAN: Sometimes the vitality is behind the dumpster. [both laugh]

WALLACE: How much of that will catalyzed into ambition? Were you, are you, intensely driven?

TILLMAN: Ambition has certainly always been there. The motivation has changed, several times. Early on it was just to escape. Escape the mundaneness. Which doesn’t, or didn’t, make for particularly great music. When I quit Fleet Foxes, that was pretty much the end. I thought I was definitely on the trajectory to washing dishes.

WALLACE: That must’ve been terrifying to do. Did all your friends go crazy?

TILLMAN: Yeah. It was sort of like, “Well, this is the end.” Being in that band was another dream that I had to wake up from—this idea that, “Well, as long as I’m playing music,” you know? That’s just not me. I’m definitely not that guy. My whole thing is about expression and exploring the conscious, and there’s nothing more unconscious than being a drummer in a successful band. “Laughs bitterly.” So I had to wake up from that. I had this little window of time, which I’ve talked a lot about—the naked-in-the-tree-on-mushrooms stuff, and I won’t diminish the significance of that event just because I’ve talked about it a bazillion times. It was a very singular moment of clarity for me, where, in this deconstructed identity state, unpacking my name and unpacking these abstractions that I had associated myself with, and realizing that I could do whatever I wanted—which you can either view as cliché or as being the most elegant of all realizations.

WALLACE: And also a call to arms, because once you realize that, you have a responsibility to go do that.

TILLMAN: There’s a responsibility, yeah. I’ve always felt like a realization, whether it was that I wasn’t a believer or something as mundane as “I don’t want to be in college” or, like, “I don’t want to be a drummer in a band,” there’s always some collateral. And, for better or worse, the collateral is evidence of the fortitude of your commitment to the realization. So I had this naked-in-this-tree moment, and then writing that novel—a term I use loosely—that comes with Fear Fun, which was just creativity devoid of ambition, I guess the realization was that I figured out how to use my voice. And how to use these things that were so innate to me that they were invisible to me all through my twenties when I was trying to be a writer. It never occurred to me to talk like myself. [Wallace laughs] But part of the problem with searching for realness, and there is some searching involved, is that you have to just end up back where you started. There’s no glory. You think you’re going to be a conquering hero or something, but you just have to be able to live with the cosmic joke that, at the end of it, you just get to be yourself.

CHRIS WALLACE IS INTERVIEW‘S SENIOR EDITOR.