FAME

“We Were Sacrificed”: Fab Morvan on Fame, Regret, and the Milli Vanilli Comeback

For more than three decades, Fab Morvan and the late Rob Pilatus have mostly been remembered as footnotes in the annals of celebrity scandal. Vilified by both the press and the public when it was revealed that their pop duo, Milli Vanilli, was lip-synching their way through two years of meteoric stardom thanks to hits like “Girl You Know It’s True” and “Blame It on the Rain,” the pair were cast as modern-day Cyrano de Bergeracs—hucksters who took our hearts and stomped on them while the real artists hid in the bushes. As is often the case, the truth is much more complicated. Today, Fab is back in Europe, pursuing music and processing a Milli Vanilli renaissance, thanks in part to their song’s appearance on Ryan Murphy’s Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story. To mark the moment, historian of bad behavior Alissa Bennett sat down with Fab to discuss greed, comebacks, and the public’s appetite for sacrificing its stars.

———

MONDAY 4 PM OCT. 21, 2024 MALLORCA, SPAIN

ALISSA BENNETT: Fab, I can’t believe I’m talking to you! I wrote about you in 2016 and was an early believer that we owed you more. You got stuck with a real Charles Dickens story, and I think it’s really important that you have a chance to talk about it now.

FAB MORVAN: It’s important because it’s not just about me. I hope the Milli Vanilli story triggers young artists to learn more about publishing and songwriting and music and producers so that they can protect themselves.

BENNETT: But it’s also a story about fame and a public hunger for celebrity that’s never satisfied.

MORVAN: It’s an insatiable hunger, yes.

BENNETT: I don’t know if people who weren’t alive at the time of the Great Milli Vanilli Crisis can understand how outrageously famous you and Rob Pilatus were from 1988 to 1990.

MORVAN: It was brief, but I feel like I lived the lives of a hundred men during that period, and then after that I lived the lives of a hundred more. I want the name Milli Vanilli to symbolize what happens when you fall and then stand back up, reinvent yourself, and fight for yourself. If you give up on yourself, you are giving up on your life.

BENNETT: How old were you when Milli Vanilli first hit?

MORVAN: I was about 22.

BENNETT: And you were already performing together by the time you met Frank Farian?

MORVAN: Frank Farian found us because we were performing with his studio musician in a band, and we’d done a few shows in a club called P1 where we hung out. I met all kinds of legends there, from Prince and Whitney Houston to Chaka Khan and Rick James. Later in my career, a lot of them were like, “Were you those two guys from Munich?”

BENNETT: When it started happening, did it feel real or did it feel like a dream?

MORVAN: When it happens, you’re not there. There were points when we would try to step out of it, but fame is so powerful.

BENNETT: Tell me how that feels.

MORVAN: It feels like a magnet. Even though you’re not always down for it, it drags you in. At first it was fun, but it turned into a nightmare. We didn’t feel right about what we were doing; we wanted to sing, but we were just walking that line, hoping that at some point we could jump

ship and find someone who really believed in us. Frank Farian never took the time to do that, and by the time we showed up, the music was essentially done.

BENNETT: A big part of what drove your popularity was your style, and the Milli Vanilli aesthetic predated your work with Farian. When everything eventually came out, the public thought your entire identity was manufactured.

MORVAN: It was very confusing for me at first, because we never thought about it and were just

being ourselves.

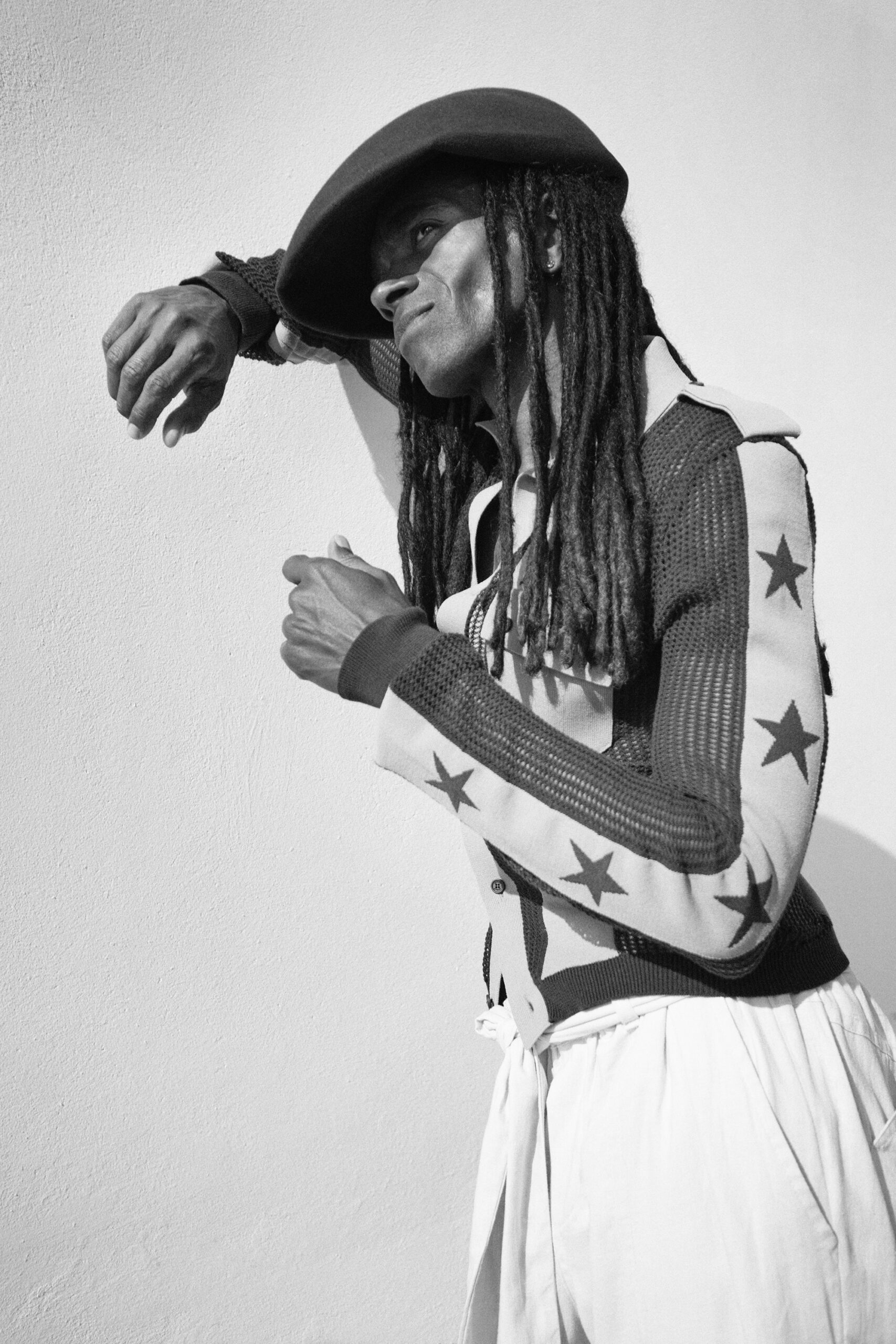

BENNETT: How did you pick your clothes?

MORVAN: We shopped a lot in the women’s section. We would look at the men’s section and think, “Looks kind of boring.” It was just natural back then to say, “Okay, that’s good, even if it’s a woman’s jacket. Looks dope on me.” We were just looking for stuff that looked right; like we’d put on a few blazers, and then we’d be standing together in the dressing room looking at each other like, “Yo man, that’s it.” It especially clicked once we got the hair—

BENNETT: You have a new collection that just came out, right?

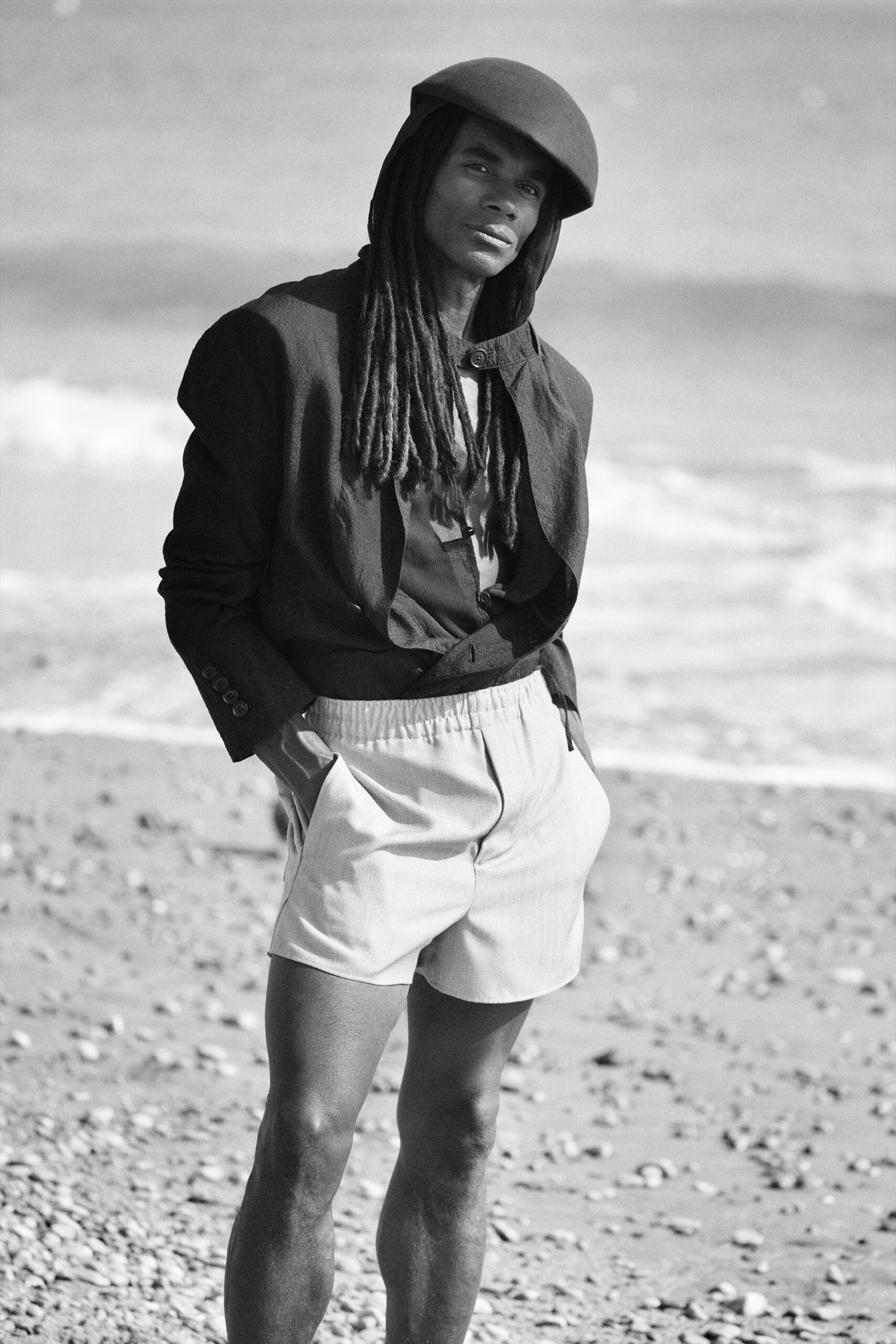

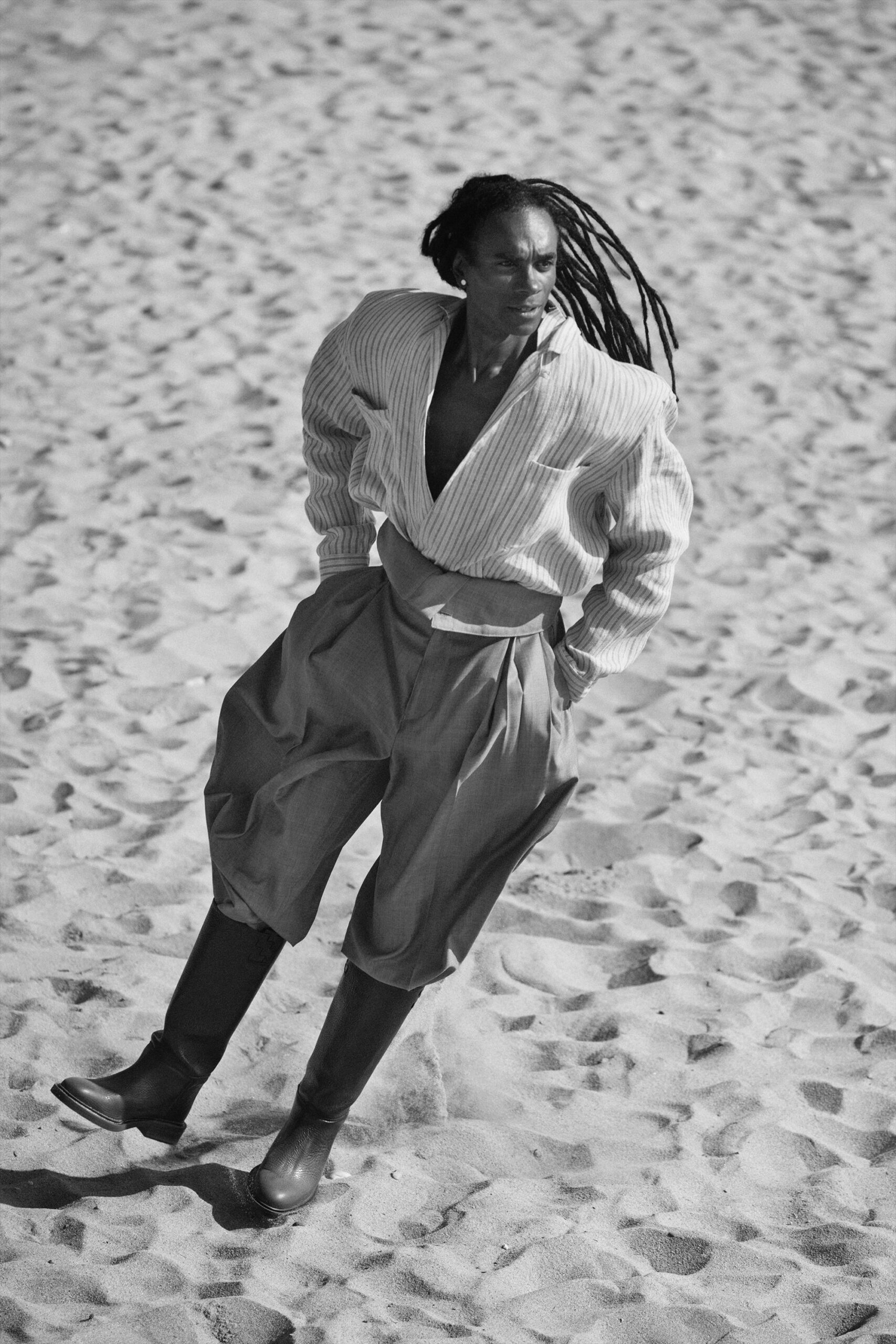

MORVAN: I was approached by Helen López from Lenifro, and she said, “Hey, I just saw your movie [the documentary Milli Vanilli], I’m so inspired. Why don’t you celebrate the Milli Vanilli style?” So we did, and I went to Milan Fashion Week, London Fashion Week, and we debuted the Lenifro x Fab Morvan collaboration. It’s a capsule collection—about eight outfits for women, a couple jackets and pants for guys—and it’s looking good.

BENNETT: It’s such an iconic look.

MORVAN: The Milli Vanilli style is definitely iconic. I see it on a lot of rappers, in their use of the leather and the shredded jeans. It’s refined and modernized now, but when I see it, I’m like, “You guys look like my kids! My stylish children!” If I may say so. [Laughs]

BENNETT: [Laughs] You may. Who were you guys hanging out with from 1988 to 1990? Tell me about Rob and Fab meeting their idols in America.

MORVAN: That was the era of the Roxbury on Sunset. It was Axl Rose and Slash, it was Mickey Rourke, it was Madonna, Sammy Davis Jr.

BENNETT: Everybody.

MORVAN: Yeah. Back then, the VIP rooms were packed with celebrities and there were no phones.

BENNETT: Better for bad behavior.

MORVAN: When phones showed up, it really changed the club scene.

BENNETT: Did you guys ever talk about what would happen when you got caught?

MORVAN: We were so close we didn’t even have to speak it. It was almost telepathic, where we could look at each other and know that we shared the same fear.

BENNETT: How deep was that fear?

MORVAN: We always knew that at the end of that tunnel, people would find out and it wouldn’t be pretty. I looked at our relationship with the public like a relationship between a couple who love each other, where one of them suddenly finds out, “Man, you were cheating on me the

whole time.” It’s like, “Oh, damn,” you know? And maybe the person who gets cheated on is like, “Okay, I’m just gonna walk away. You don’t get any more of my energy,” but maybe they’re the other type who’s going to get in your face and say, “Why would you do that to me? I want an explanation.” I always felt like the fans were going to be divided like that, and they were. But there were also people who wanted to capitalize on the fact that we were being torn down. It was terrible. Really painful.

BENNETT: Made worse by drugs and alcohol?

MORVAN: I think that was the peak of our self-abuse.

BENNETT: Was cocaine your thing?

MORVAN: I was more of an MDMA type, because I’m more into communication and creativity. But Rob, he was the opposite.

BENNETT: You were the good boy, and he was the bad boy.

MORVAN: There was definitely some of that. They used to call us das Gute und das Böse, the good one and the bad one, but I think that energy struck a perfect balance.

BENNETT: People could pick which one of you they loved.

MORVAN: That’s right, and we gave a lot. I would always tell myself I was doing everything I could to give everything I had, every ounce of my sweat. I always thought, “I’m gonna reach you,” and hoped that maybe one day, I’d get another opportunity to come back and live my dream. Onstage, we would forget how nerve-wracking the whole situation was and just kind of split. It was like there were four people onstage: There was us, and there were the voices.

BENNETT: Oh, that’s incredible.

MORVAN: You know when people explain what it’s like to smoke crack? You go up and then boom, you come right back down? That’s how it was. When we got off the stage, it was like, bam! “Okay back to reality.”

BENNETT: It must have made you feel very outside of your body.

MORVAN: Totally. It was an out-of-body experience, but even when we had very little left, we’d hear the roar, and that roar is electric. We would have been out partying all night, but we’d get backstage, have massages and acupuncture, and then once we heard the audience scream, we’d be ready. There would be 25 or 30 thousand people screaming, and we’d forget everything. We forgot who we were, and we became Milli Vanilli. Suddenly, each of us would become this persona and then stay there. Occasionally I would realize, “Oh, yeah. That’s actually not my voice.”

BENNETT: You won a Grammy in 1990, and in your acceptance speech, one of you said, “This is for every artist with a dream. If you’re in this room or not, this is for you.” I think in some way, you were giving this Grammy to the version of yourselves you weren’t allowed to be.

MORVAN: In reality, we could only partially accept it, and that’s why we gave it away to all those dreamers who aspired to become what Milli Vanilli symbolized.

BENNETT: Including yourselves.

MORVAN: Yeah. They were us.

BENNETT: After you won, you went to Frank Farian and said, “It’s time for us to record our own album.” And he was like, “No fucking way.” I don’t know what your relationship ended up being with him later on.

MORVAN: There was no relationship.

BENNETT: It’s like Hansel and Gretel: “Come on into the candy cottage! You’ll love it here!” What you didn’t know was that as soon as he got you inside, he was gonna fucking eat you. Right after you told him he had to let you record an album, he gave a press conference where he basically said, “Guess what? They’re actually total frauds who didn’t sing a note on any of these songs, and isn’t that amusing, haha?” And then he got away without any consequences.

MORVAN: Our plan was to push him to the brink so that he’d say, “Okay, let’s see how you do without me,” but he was so calculating, and he knew that if we went to New York and told the world, that nobody would want to touch us. We were in the process of jumping ship, and I don’t know if he knew about that and it’s whatnprompted him to do it. When that cat came out the bag, it was over. The media knew they had something good, and they were going to milk the hell out of it.

BENNETT: Right, and that’s the full cycle of fame. First someone makes money because everyone wants you, then someone else makes money because no one wants you at all.

MORVAN: That’s right, that’s the tear-down process.

BENNETT: One of the interesting things is that the primary narrative then was that you couldn’t sing, but it’s not true; you actually can.

MORVAN: That was really damaging to me. To this day when people hear me, they’re like, “But I thought you couldn’t sing.” I’m like, “Yo, listen, you swallowed that Kool-Aid really nicely, but it wasn’t true.” That’s part of the narrative that I’m so glad is being rewritten.

BENNETT: And if anyone doubts it, you have new remixes out. They can go listen now and apologize for being wrong.

MORVAN: There’s a new version of “Girl You Know It’s True” and an acoustic version of “Blame It on the Rain.” Definitely more to come.

BENNETT: There’s footage of a press conference the two of you gave in 1990 to a room full of journalists who were circling like vultures and wondering how they were going to get your corpses off the stage.

MORVAN: The weirdest part about that was that some people were so openly racist. It was pure vitriol. The atmosphere was so thick with hate, and people were so angry that they were not refraining from being racist. It was partially by design, to get us to react, but we never stepped out of character. We did it to say, “We know we were wrong, and we came here to let you know, ‘Hey, we want to give this Grammy back.’” That’s what we wanted, because we didn’t think we deserved it, and it didn’t feel like it belonged in our house. But when we informed them that we were going to give it back, the Los Angeles Times told NARAS [the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences] and then they jumped the gun. This is one of the most important misconceptions for me. We actually wanted to give it back, but the press made it seem that the Grammy federation forcibly reclaimed it from us. And now, 30 years later or so, we are on the Grammy ballot again, this time for Best Music Film.

BENNETT: I think we owe that to you. Did you feel like you’d been sacrificed?

MORVAN: Oh, yeah, we were sacrificed, scapegoated, used. Over $300 million was made on Milli Vanilli, and the money that we generated gave birth to other artists in the ’90s. Some people seem to forget that part, but it’s okay. The majority of those labels and the majority of artists that were signed during that time are now either bankrupt, dead, not doing very well, or fighting for themselves. It’s sad, because by design, artists are not supposed to make it. That’s the way contracts are designed: You get your first album, you owe money on it, then you keep going on the second one, and by the third one, you still owe on the first one and the second one.

BENNETT: It’s like a hole you can never dig yourself out of.

MORVAN: Now I feel like I’ve got a chance to go into a new and exciting story. A new chapter, and people are slowly starting to read it. I’ve been working on that chapter for a long time.

BENNETT: I remember the whole thing unfolding, and we really wanted penance from you. I was thinking about the Carefree gum commercial that you did, where they had you pretending to sing opera until the record skips. It’s like you were trying to get in on the joke so that people would forgive you. It’s very Catholic.

MORVAN: There was an article in Vibe, “Milli Vanilli Died for Your Sins.” We paid, and they scapegoated us. The executives and producers and the labels were the ones who were able to put their kids through school, buy houses, go up in business, and remain untouched.

BENNETT: People were so mad. Fans waged class action lawsuits against you!

MORVAN: We were even brought up on criminal charges in one county, because some kid said he couldn’t sleep anymore.

BENNETT: David Stalder was his name.

MORVAN: Oh my god. You know a lot.

BENNETT: I told you, I’m an expert. I know your life very well.

MORVAN: My god. You went through, like an archeologist.

BENNETT: This is what I do, and I did it for Milli Vanilli before anybody else did it. I’m just gonna say that again.

MORVAN: Thank you.

BENNETT: I was thinking about you this week when Liam Payne from One Direction died. I thought there were a lot of similarities between him and Rob.

MORVAN: Well, I think it’s important that we finally opened the conversation and are able to look at mental health. When I went to rehab and I talked to psychiatrists, they told me, “Hey, you see the edge over there? Once you fall, there’s no way you can get back.” The pain of that is very real. There is a void that gets filled by public attention, but that love is not real love.

BENNETT: It probably feels especially real when it’s gone.

MORVAN: It does feel real, but in the end, once you have a relationship—a true relationship—you’re like, “Oh, okay, that’s real love.”

BENNETT: You’re doing all kinds of things again. You have the capsule collection, you’re recording and performing music. What’s the difference between what you thought about being famous when you were young and how you see it now?

MORVAN: I never really think about fame, but I do come from a family of musicians. People don’t know that—traditional Caribbean music. I have a lot of composers in my family, so it was in the DNA. When it comes to what I am musically, you will discover that you haven’t seen anything yet. It’s something I was born with, and when you’re born with something, it stays with you forever.

Tank Top And Belt Isabel Marant. Pants Ami Paris. Hat Javier Guijarro. Cumberbund Stylist’s Own. Socks Falke. Shoes Saint Laurent By Anthony Vaccarello.

Grooming: Itziar Nzang using Kevin Murphy and Dior Cosmetics.

Photography Assistant: Marc De Miguel.

Fashion Assistants: Breno Vasquez and Paula Ferragut.

Production Management: Mariona Calathea.

Post-Production: Giuseppe Fazio at La Cápsula.