Into the Void

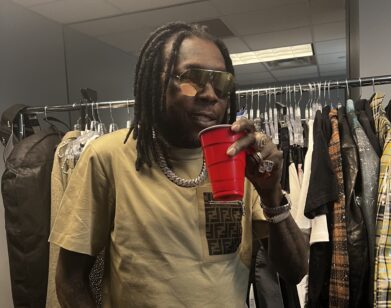

ABOVE: EMA. PHOTOS BY SHOJI VAN KUZUMI

For Erika M. Anderson, writing music is catharsis. “I go into a trance state and write about something, and then I feel lighter and so much freer,” she says. Whereas 2011’s critically adored Past Life Martyred Saints cast its gaze inward, the Portland-based singer’s second album as EMA, The Future’s Void (Matador), out tomorrow, shows grander ambitions in both shape and scope. Over her signature electro-fuzz sound, Anderson, unwavering in her lyrical conviction, tries to make sense of a world drunk on technological evolution, as in her paranoid ranting in “Neuromancer” that “they know more about the things that you do / They know more of it than you do / They know!”

DAN HYMAN: Did your writing process evolve with this album?

ERIKA M. ANDERSON: I think one of the things that happened with this record was that I was kind of bored. Every time I would try to sit down and write a song on the guitar, I would be kind of bored. You want to do something challenging that you don’t know anything about. So I was like, “Okay, let’s bring in a bunch of electronics.” And I wanted to learn how to use these things so I’d have them in my palette for the future.

HYMAN: The lead track, “Satellites,” hits the listener with a blast of that electronic vibe right from the outset.

ANDERSON: That’s harkening back to my West Coast noise days, where I used to go to, like, three shows a week of people playing oscillators in dank warehouses. I feel like that sets a sequence for the record in some ways. It’s a very binary sound, you know? It’s the harsh noise and the deep bass and this faux-human element comes in. It’s supposed to sound like claps, but it’s obviously mechanical claps. That was one of the first ideas that I had for the record, so it made sense that it would go first.

HYMAN: The album is a particularly heavy listen. You seem to throw yourself emotionally into these projects.

ANDERSON: It definitely is. That’s one of the reasons I do it. It helps me. I’m from this stoic Midwest background, and I’m an Aquarius. I don’t even know half the time what I’m feeling; it’s deep in my subconscious. I go into a trance state and write about something and then I feel lighter and so much freer. That’s something I discovered early on with Gowns. After I wrote “White Like Heaven,” I was just completely unparalyzed. So I’ll get in these places where I feel overwhelmed or I feel paralyzed or I feel stuck, and I feel better after I write.

HYMAN: The music you make as EMA is poppier compared to your Gowns days. Though I suspect many will still find it heavy and dark.

ANDERSON: It’s so contextual for me. I spent so long in this kind of West Coast, California experimental and noise scene that I thought Past Life Martyred Saints was like the poppiest thing ever. And then I would actually listen to what is mainstream, not even pop, like indie-pop, and I’d be like, “Okay, wow. I’m totally not making this kind of music.” I try and make things that can be enjoyed on many different levels, because I can get a kick out of things on many different levels—things that will reference other sounds in this fun way. I try to have an element of play in there and say things that maybe take people by surprise. Lately, my inspirations have been trying to see as much contemporary art as I can or read as many weird books as I can—almost more than music.

HYMAN: Is it then about conditioning your senses to be more aware of your surroundings?

ANDERSON: I just let whatever in. Your subconscious mind will come up with these connections. And it’s cool because, all of a sudden, you realize that maybe you are on the same trip as a lot of other people. I feel like if you keep yourself open to things and then take lots of naps and lots of walks, you can get on the trip with others. [laughs] I’ll just pick up books on the side of the road. Portland has a bunch of free libraries. I’ll read anything. Right now I was just finishing the Mike Tyson autobiography.

HYMAN: How was that?

ANDERSON: It’s a trip. It’s pretty long. It’s like 500 or 600 pages. And that’s kind of a long time to spend with Mike Tyson.

HYMAN: It’s impressive the way you’re able to dissect your own songs. Many artists are reluctant to do that.

ANDERSON: I like being able to talk to people and explain my work. It also gives me insight into things. Doing interviews is just another step in that. I don’t mind that. But photos are really difficult. I feel very confident in my ability to make sounds and manipulate sounds to create the message I’m trying to make. But the visual meaning is so different. And it’s so been taken over my advertising that it’s so hard to get a fresh image across that doesn’t look like an ad. How do you be a blonde woman in this world without looking like an advertisement?

HYMAN: That segues perfectly into talking about your song “So Blonde.”

ANDERSON: “So Blonde” to me is funny: it’s like this meta-grunge thing that’s kind of ambivalent about its protagonist. When I see these internet babes go from this real person or this hyperrealistic photograph get degraded down to a line drawing or pixels, at what point does the semiotics of the blonde babe lose its representational power? I don’t know. Maybe they don’t. Maybe as long as you can kind of make out that 36-24-36 and blonde hair, maybe it’s still sexy? I don’t know, but it’s an interesting question.

HYMAN: You incorporated natural noise—a garbage truck in “100 Years”—on the album.

ANDERSON: One thing I definitely have learned on this and keep coming back to is that I try raising the stakes and bringing improvised elements in. That’s so important to make songs be alive. It’s kind of a John Cage thing that I picked up secondhand from art-school kids. But it’s still a pretty cool idea.

THE FUTURE’S VOID IS OUT TOMORROW, APRIL 8. FOR MORE ON EMA, PLEASE VISIT THE ARTIST’S WEBSITE.