IN CONVERSATION

“Do You Own a Jazzmaster?”: Devon Ross and Thurston Moore Geek Out on Vintage Guitars

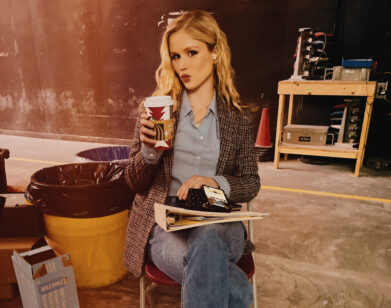

Devon Ross and Thurston Moore, photographed by Phoebe Fox.

When recounting his first face-to-face meeting with his rock and roll protégé Devon Ross, rock legend Thurston Moore, the founding member of Sonic Youth, fired off a joke. “You punched me in the face and I said, ‘Hey, aren’t you that chick in Irma Vep?’” That’s not really how it went down, but it is a testament to how close they’ve become since first being introduced at the Cannes Film Festival, where Ross was on hand for the world premiere of the HBO series which Moore scored. Since then, he signed her to his label, Daydream Library, under which Ross released her debut EP Oxford Gardens earlier this year. Now, it’s Moore who’s gearing up for a record drop: his ninth solo album, Flow Critical Lucidity, comes out today, so he and Ross linked up over Zoom earlier this month to chat about their fashion icons, favorite vintage guitars, and living out of a van.—ARY RUSSELL

———

THURSTON MOORE: Do you remember how we met? It was at that Ramones gig when you jumped off the stage and landed on my size 14 feet and I started yelling at you.

DEVON ROSS: I remember that like it was yesterday.

MOORE: You punched me in the face and I said, “Hey, aren’t you that chick in Irma Vep?”

ROSS: I was like, “Are you that guy in that band?”

MOORE: I guess we met at the Irma Vep screenings at Cannes two years ago. I didn’t know you at all, I just knew your character in that show. I was doing music for it, obviously.

ROSS: Obviously.

MOORE: You came up and introduced yourself, which was really nice. Nobody does that. Then you asked about sending some music for us to listen to, knowing that we had a record label. I listened and loved it, so we put it out as a 12-inch EP, Oxford Gardens, and the rest is history.

ROSS: Yeah, and it’s funny. I didn’t even sing when I met you guys.

MOORE: You weren’t even singing?

ROSS: I wasn’t, I was playing guitar with my friend. But I knew that I was going to at some point. It happened way later.

MOORE: So it wasn’t exactly a dream of yours to start a rock and roll band and put out a rock and roll record, as you did in the last two years?

ROSS: When I was 16 I was obsessed with being in a band, but I couldn’t find anyone to join and I couldn’t find a good name, so I was like, “I’ll just be the best guitar player ever.” I tried that and then decided I wanted to be a singer.

MOORE: You’ve been playing guitar your entire life, haven’t you?

ROSS: I started when I was 14. I mean, they were always around me when I was younger, so I always picked them up.

MOORE: I started kind of late. I always wanted to be a rock and roll guitar player, and I thought it was impossible, because when I was a kid in the early seventies, guitar players were all about having established technique like, Jimmy Page and Hendrix or Johnny Winters. I figured maybe I’d be a drummer instead, but I couldn’t keep a beat. But I thought, “I’m just too tall and dorky to be a singer.” There were no tall dorky singers on the scene. That’s why the Ramones were so important in ’76, they changed my life. But I didn’t start playing real guitar until my later teen years. You probably always had guitars laying around your house, right?

ROSS: Yeah, always. I wanted to learn all the techniques, and I spent pretty much four years in my bedroom playing along to Freddie King and Charlie Christian. That’s why I hadn’t written songs yet. I was like, “I want to be the best guitar player before I do that.” Then I heard Sonic Youth and I was like, “Oh, maybe I could do it now.” That kind of music changed my perspective on what playing guitar meant.

MOORE: When I started playing, I immediately got involved with experimental guitar players where it was cooler not to play in any traditional aspect, but I never lost my respect for that. And that’s what made Sonic Youth, Sonic Youth. We actually were a rock-and-roll band, much to the chagrin of the noise purists who thought at first that we were their trophy band. You seem to have a pretty wide knowledge base of real classic, heady, heavy rock and roll music. Where does that come from?

ROSS: My dad’s a classic rock nut. That’s what was played in the house. There’s music on from when he wakes up to when he goes to sleep. He’s also just a purist who was like, “This is good music. That’s bad.” I remember when I was in middle school, my friends were finding out about The Smiths—no disrespect to the Smiths—but I was playing it in my room and my dad came in and was like, “No Smiths in this house,” and just closed the door. It kind of fucked me in the end because when I was in my early twenties, I was like, “Pavement’s bad, but I like them. Is this wrong? ”

MOORE: Well, it’s not like you were playing Throbbing Gristle in your bedroom.

ROSS: No, I was pretty well-behaved.

MOORE: When did you start modeling?

ROSS: I started modeling when I was 15, which is also when I dropped out of school.

MOORE: Did you have some sense of designers who you thought are more connected to the rock and roll that you loved?

ROSS: I always watched Gossip Girl and The OC and those teen 2000s shows, which are very fashion-based. I also always loved Vivienne Westwood, and I was really into what the Sex Pistols wore. I was always more into what musicians were wearing than in fashion catalogs.

MOORE: Have you ever been to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland?

ROSS: No.

MOORE: You guys should go there. I was taken aback because it has so much to do with the clothing that rock and roll people wore throughout history. There’s instruments, guitars, drums, and sometimes a car or two, but a lot of it is the clothing that Hendrix wore or Janis Joplin wore, or even Joan Jett. At some point I was really cynical about it. I was like, “God, they should just change the name of this building to the ‘Rock & Roll Hall of Clothes.'” But in a way, it goes hand in hand. The clothing is as vibrational as the music, which is just purely sensual in a way. When Sonic Youth was coming up, it was about muting a lot of what was expected for a rock and roll band to present, which is the color and the flash and the glamor. We came out with ripped jeans that had paint splatters on—that’s what you wore that morning and you wore it that night on stage. It was its own sort of aesthetic presentation as opposed to dressing up in Malcolm McLaren, Vivian Westwood, or in bondage or leather and lace. Even Bowie glam feather boa stuff. To actually just dress in a T-shirt and jeans and a pair of trainers was our conscious decision–it wasn’t just us wanting to look like non-rock, but being non-rock was a statement.

ROSS: The first few shows I played, I didn’t even know that people changed into other outfits. I was like, “I’m just wearing my jeans.” But there’s always been people like Susie Quatro and Joan Jett with the leather suit or the space suit, that I always thought were so cool. I feel both ways about it.

MOORE: I never was really inspired to dress a certain way, even in punk rock. I always felt like it was a little too premeditated. But it got really extreme at some point in our scene where all of a sudden you had a lot of musicians and bands on stage who basically looked like they wanted to be anywhere except for there. They had their backs turned to the audiences, staring at their amps while they were like, “Why?”

ROSS: I would love to do that sometimes.

MOORE: There’s something really alluring and seductive about that: The “No Wave” artist who doesn’t acknowledge the audience. Are you writing any new songs? Because you should be.

ROSS: I was just writing one before you called.We’re chilling out now after traveling and stuff.

MOORE: After that arduous summer tour schedule.

ROSS: Yeah, that was a grueling tour we just did.

MOORE: We just did that tour with you guys playing all the Rough Trade record shops throughout England, which was fun. Would you get in a van and crisscross the USA for two years and live off fumes?

ROSS: No, because I grew up going on tour my whole life, but in such a different way. I’ve had experience traveling and being on the road for months, and when I put music out, I don’t think I understood that it would create separate fan bases or separate entities. There’s people that are fans of my music that don’t know that I act or just found me on Spotify.

MOORE: If I do anything on social media where I talk about anything that has nothing to do with music, I always get comments saying, “Stick to the guitar, buddy.”

ROSS: No one ever wants you to do other stuff.

MOORE: I’ve always been attracted to people who are interdisciplinary. I wanted to ask you about your acting career. I know that you have this new film that is out that’s called My First Film. How did you get involved with Zia Anger?

ROSS: Zia is the best. I auditioned for that film in 2021, right before I went to the premiere for Irma Vep. I did two auditions with her and I did a chem read with Odessa [Young], who’s a lead in the film. We filmed it in upstate New York, and it was a female director, female DP. It was the best vibe. It felt like summer camp.

MOORE: Is this actually her first film?

ROSS: This is her first feature film, but it’s about the process of her trying to make her first feature. It’s like a hybrid documentary-film.

MOORE: It looks kind of meta, from the little bit I’ve seen.

ROSS: It’s pretty meta, which is funny because I did it right after Irma Vep. I was just doing this film about making other films, so there’s crew guys standing around that are the “film crew guys,” and there’s the actual one. It gets a little confusing.

MOORE: Well, even the few times I was on set for Irma Vep, I remember Alicia saying she got confused about who was actually in the film and who wasn’t.

ROSS: It was my first time on a big set, so I was already confused. But I was like, “Who do I ask for water?” I was like, “Can I go to the bathroom?”

MOORE: But you were astounding. Everybody was talking more about your character than anyone else in that film. You’re the assistant to the Hollywood actress who’s trying to do the hip European film. You’re along for the ride, but you’re also kind of a cynic, and you’re reading Jonas Mekas and film theory, and you also have this real young riot grrrl vibe where you’ve already figured out the foolishness of the patriarchal world. It’s such a great character and you pull it off so magically. Has it helped you in finding other film work?

ROSS: It definitely helped. I literally never acted before that. I was so scared. I think the first scene in the film is maybe the first scene that I filmed and I didn’t know what I was doing. When I was doing press and they’d ask me about film, I was just like, “Keith Richards is cool.”

MOORE: Do you think you would ever get involved with getting on the other side of the camera?

ROSS: I would love to. I mean, my god-sister Zoe Kravitz just directed her first film and it’s amazing.

MOORE: Yes. I know that you can just pick up a camera and make a film, but in some ways, you really need to be on set and see how a film is made. It’s like people who play free improvised music or free jazz or noise music; it has less to do with the strictures of structure and has more to do with making a statement. You can really tell who is genuinely devoted to it in a way where they’ve studied that vocabulary and those who just sort of jump in raw to it.

ROSS: I’ve worked with a few first-time directors and with some you can tell they don’t know what they’re doing. Obviously you’re freaking out if you’re doing something for the first time, and it’s doable, but it also definitely helps to know how stuff works first.

MOORE: I’ve only seen it a little bit, being on certain sets here and there through the years. Just seeing how actors contend with the relationships they have with each other and with their directors and cinematographers, it is such a curious world. There’s so many cooks in the kitchen. Being in a band, you still have some sense of your own sort of solitude, where you can do what you do in a room with a guitar and the door closed.

ROSS: Yeah, but with acting, you’re so lucky to get one role in a year, you know what I mean? That’s why I love doing more than one thing. I love having something else to do when I maybe can’t do the other.

MOORE: I guess it’s a matter of control. Even somebody like Zia Anger making My First Film, she’s just like, “I’m making my film.”

ROSS: It’s fucking hard, too. She’s tried to make that film for so long and it didn’t work out. And she’s making a documentary about her trying to make it, you know what I mean?

MOORE: Yeah.

ROSS: It can take so long sometimes. I’ll do an audition that I’ll hear back from two years later, and they’re like, “We’re still trying to make this.” It’s so hard, especially now, to make anything.

MOORE: When I want to watch a film, I’ll go online and 99% of the films I have no knowledge of. I would say 90% of those are just rehashed zombie comedies or all these weird sort of horror grade Z films. So many of them are being made.

ROSS: There’s so much bullshit these days it’s insane. But honestly, that just goes with streaming, which is the same with music to a certain extent. People are so starving that they just need to pump out anything that anyone thinks of.

MOORE: And I suppose there’s people who are funding it. What guitar do you have? What’s your go-to?

ROSS: I have a few. My Mustang is probably my go-to, I bought it last summer. This is the first guitar I ever bought myself. But I have my gold top Les Paul at home in L.A., which I love.

MOORE: A Les Paul and a Fender Mustang are quite different from each other.

ROSS: Well see, my dad is a purist again. He only has Les Pauls and Strats. When I was like, “I want a Jazzmaster,” he’s like, “I’ve got no Jazzmaster. I got Strats and Telecaster.”

MOORE: Has he ever tried playing a Jazzmaster?

ROSS: He told me never to get a Jazzmaster, and then I got one. I think I got a fucked-up one. I was like, “This thing sucks.” He was like, “I told you. It’s the worst guitar I ever met.” I love this man, but he has very, very strict opinions.

MOORE: Dude, you need a Signature Thurston Moore’s Jazzmaster.

ROSS: I know. I don’t think he’s ever played a good Jazzmaster. I bet he’s never even tried it.

MOORE: There’s nothing like a good pre CBS-era Jazzmaster, like between ’58 and ’68, when they’re set up correctly. That was the guitar that Tom Verlaine was playing for Television.

ROSS: That’s why I just got the first white one that I saw. And it’s horrible.

MOORE: Yeah, the Japanese-produced Jazzmasters in the nineties are pretty plasticky sounding. You have to get a really good classic pre-CBS production one.

ROSS: I know. They’re so expensive these days. It’s impossible.

MOORE: Who’s we? Oh, you and Marlon.

ROSS: He’s right there.

MOORE: Does Marlon have a Jazzmaster?

ROSS: Marlon, do you want to be interviewed by Thurston Moore?

MARLON SEXTON: Boy, do I.

MOORE: Do you own a Jazzmaster?

SEXTON: Yeah, but it’s not a Fender.

MOORE: Well, I don’t mean to imply that you guys need Jazzmasters.

ROSS: We want them, don’t get us wrong.

MOORE: We can talk to Fender about this. If I talk to Fender, you can talk to Louis Vuitton and get me some rock and roll guitar cases.

ROSS: I’ll get you a truck that the bed comes out of. You can get a little chair with it.

MOORE: I like that. Or give me some Miu Miu luggage. Does Miu Miu make luggage?

ROSS: Yeah. We love Miu Miu.

MOORE: That would be a great trade.

ROSS: Deal, dude.