DJ Harvey’s Tables Keep Turning

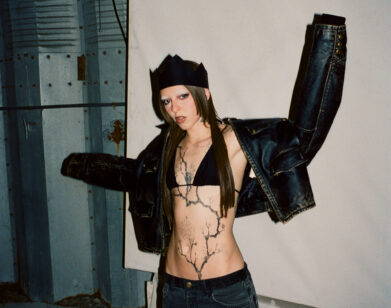

DJ HARVEY. PHOTO COURTESY OF NATE BRESSLER

With a career that spans across an impressive array of genres, continents, and decades, Cambridge-born Harvey Bassett (aka DJ Harvey) has been called a musical ambassador: his eclectic mix of disco, garage, and house is now a staple in DJ culture. Starting off young as a drummer, Harvey bought his first pair of decks and joined up with the Tonka Deaf Crew, an art collective that threw warehouse parties throughout London. Harvey’s star continued to rise, and the DJ started his own party, “Moist,” at London’s Gardening Club to much acclaim. A number of residencies soon followed, and Harvey became the first British DJ ever invited to The Ministry Of Sound, a London club devoted to America’s house music scene, where he began a residency and released a compilation mix of his sessions.

Harvey’s kept his cult-like legend alive throughout the years, still constantly touring and releasing new projects, including his recent rock project Map Of Africa, a collaboration with fellow former Tonka crew member Thomas Bullock. We spoke to Harvey, whose new record Locussolus is available now, about his punk-band upbringing, his first trip to America, and how the nightlife scene has changed (or hasn’t) over time.

ALEX CHAPMAN: Hi, Harvey. Where are you?

HARVEY: I’m in my new Venice “pleasure palace.”

CHAPMAN: [laughs] In Venice Beach?

HARVEY: It’s on the canals of Venice Beach, on what’s known as the “silver triangle.”

CHAPMAN: Very nice. So you got your start in punk when you were a kid, right?

HARVEY: I was very young at the time—anything my parents didn’t like [I liked]. A classic teen-angst type rebellion. If it wasn’t punk, it would’ve been rock and roll or some other similar movement of the time. As far as being in a band is concerned, it seems like when I was in school, that’s what you did. We’d get together and practice and jam along together, get little gigs, and that was basically it. I was in a couple of bands at school, and then joined a band with some older guys. I was maybe 12 or 13, and some of the other guys were in their late teens, which isn’t a big difference, but it was kinda hip to have a baby drummer at that point.

CHAPMAN: What was that band called?

HARVEY: That band was called Ersatz—we started doing some quite serious gigs and got some singles out. John Peel, the famous Radio 1 DJ, was championing our music on the radio, which was very exciting. I thought I’d arrived at that point, until I discovered that the bass player’s bathroom was full of all the records we hadn’t sold. [laughs]

CHAPMAN: And so it goes. How did you go from there to DJing?

HARVEY: I’ve always played in bands—to this day; I’ll still play session drums and stuff. But the full transition into DJing was probably a few years after Ersatz, just with the discovery of hip-hop culture, beat manipulation, or turntablism, as it’s called these days.

CHAPMAN: Did you see things you liked more in DJing, or different things it had to offer that a band didn’t?

HARVEY: Well, if you are in a band, it’s like having four girlfriends. And then your girlfriends get girlfriends, and it gets very complicated. As a DJ, you can actually determine everything that’s going on as a one-man band. So when I started hearing the early hip-hop records coming through, [I heard] DJs manipulating beats, and as a drummer, that’s kind of what I already did. So I thought, “I can still manipulate beats, be the master of ceremonies at the same time and be an entertainer.” I sort of slipped into DJing like that, and then really got to understand more about providing an atmosphere and doing it for a long period of time. It wasn’t an overnight sensation, as it were.

CHAPMAN: So then when did you have your first interaction with America? I know that had a big influence on your DJing.

HARVEY: My good friend Chocky—which is short for Chocolate—used to DJ as apart of the Tonka crew back in the day. His father was killed in an accident in a slaughterhouse, and, being America, the family sued, and off his inheritance Chocky bought me a ticket to New York City. He visited once before and came back with some hip-hop records, Adidas shoes with wide laces, and all these weird fashions and phrases, like “chilling out” and “def.” I came over in 1985, basically on a voyage of discovery, to find hip-hop in many respects. We hung out in Washington Square Park and hung out with the Rock Steady Crew, and ended up going to the reopened Studio 54—we went to every major hip-hop nightclub in New York City at that time. Everywhere: Latin Quarter, Devil’s Nest, Save The Robots, Area, The Roxy, Reggae Lounge—even places like The Saint. But then we went to Paradise Garage, which was interesting….but I wasn’t looking for gay disco, I was very much looking for straight hip-hop. [laughs] I remember The Saint was a big sleaze hall at the time. You had the big planetarium projectors, and the balcony with like 1000 guys orgying away up there. [laughs]

CHAPMAN: That sounds pretty wild. I feel like the drama and “glamour” of nightlife has dissipated over the years, which obviously is something people argue about from time to time.

HARVEY: In some respects. It’s from night to night, depending where you go. The ’90s—I’ve spoken in many respects about the tenures of disco in the ’90s. I was playing three parties a week for 10 years, but it was good and bad. We were complaining about the commercialism of dance music and the “super clubs” and stuff like that, and now that’s gone. We’re looking back and saying, “Hmm… that actually wasn’t so bad.”

But it’s very difficult with the “back in the day” thing; I’m not really one for looking back and going, “Oh, that was the greatest time.” I think right now is sort of back in the day. I just DJ’d this past weekend at Santos Party House, which was as good as it’s ever been—a beautiful, big nightclub in New York City with a fantastic sound system and a really wonderful, intelligent, interesting, dramatic, glamorous crowd. It was fantastic. Playing great big records to a great, big club—it reminded me of, in many respects, something like the Roxy or the Sound Factory or any of those larger New York venues that do have the genre, and do have the reverent and do have the history. People were asking me what the ’90s were like in the ’80s and what the ’80s were like in the ’70s. I was very young in the ’70s, but I did dance my first 24-hour session, so I suppose I’ve been dancing for a long time.

CHAPMAN: 24 hours?

HARVEY: I don’t think it was the first time I stayed awake for 24 hours, but I danced for 24 hours to raise money for my local youth club. My mother had a little clipping from the newspaper [about the event] and it said something like “They Could’ve Danced All Night—And They Did.” [laughs]

CHAPMAN: So tell me about your new record. It’s being called your “debut” by some.

HARVEY: My project before this was “The Map Of Africa,” and that was an exercise in songwriting for Thomas Bullock and me. The music was more designed for a bar, whereas the new project is more dance-based. As far as this being my “debut album,” I think that’s just silly marketing, really. I’ve been making records for years—this isn’t my debut anything. But I think the main thing about this record is the focus on the dance floor. And [International Feel label boss known only as] Mark basically came to me and said, “Here’s the production budget, now go and make some music,” and that’s basically what we did, and the project is a result of that.

CHAPMAN: I look forward to hearing it. I’m assuming you’re going to tour for the album?

HARVEY: I’m just about to embark on an amazing European tour—12 or 13 dates in a month or so, including gay pride weekend at the Berghain/Panorama Bar, which I’m very excited for.

DJ HARVEY’S LOCUSSOLUS IS OUT NOW. HE WILL CONTINUE TO TOUR THROUGHOUT THE SUMMER.