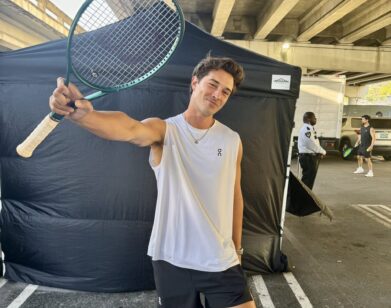

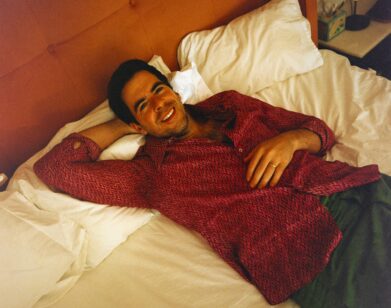

Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah

CHRISTIAN SCOTT IN NEW YORK, MAY 2017. PHOTOS: DAVID NEEDLEMAN/JONES MANAGEMENT.STYLING: JOSHUA LIEBMAN/HONEY ARTISTS. GROOMING: NATE ROSENKRANZ FOR HONEY ARTISTS USING YSL TOUCHÉ ÉCLAT. RETOUCHING: FEATHER CREATIVE.

Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah wants to change the world through music. He might even be in a position to do so. Born and raised in New Orleans, Scott started playing the trumpet when he was 11 years old. A year later, he was studying with his uncle, the great saxophonist Donald Harrison, Jr. By his early teens, he was touring the world, living the life of a much older jazz professional.

Now 34, Scott has released a dozen albums and has received two Edison Awards. He has his own label, Stretch Music, and his own app, also titled Stretch Music, which serves as an “interactive album” allowing listeners to customize Scott’s 2015 LP as they play along. He has his own selection of horns, which he designed with the help of his identical twin filmmaker brother, Kiel Adrian Scott, and is currently touring Europe. He is also in the midst releasing a trilogy of records to celebrate the centennial of the first jazz recordings. The first one, Ruler Rebel, came out March 31, and was followed by the release of Diaspora last week. This autumn, the trilogy will conclude with The Emancipation Procrastination. But most of all, Scott is passionate and erudite: when he plays, you listen. When he talks, you want to listen too.

EMMA BROWN: You’re from Louisiana originally and studied at Berklee College of Music. What made you decide on Berklee?

CHRISTIAN SCOTT aTUNDE ADJUAH: I was really excited about having the opportunity to go to school with people from a myriad of musical contexts, that wanted to share and that weren’t interested in the conservatory model. I went to the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts [before that], where most of the notable New Orleans musicians went to school. It’s a very specific path that they put you on to learn this music, and I was interested in having an alternative way of thinking. I liked the idea of being in a class with someone from Osaka, Japan, and at the time they might have been dressed from head to toe in FUBU and liked the Wu Tang Clan. Then there’d be a person from Bogota who likes blues and you’re like, “How does this even happen?” But to have the opportunity to make music with those people, to learn and grow with people from different cultures of music, and not to have the conservatory-style judgment about what it is that you’re doing was something I was highly interested in. That’s why I chose Berklee. They also gave me a full scholarship.

BROWN: How old were you when you got your first horn?

SCOTT: I started playing trumpet when I was 11. My mom and my grandmother bought me Bach TR300 trumpet, and then I started to study with my uncle Donald [Harrison, Jr.], who is a legendary saxophonist. He played with Miles Davis, County Basie’s orchestra when that was winding down after Bacie died, Lena Horne, Roy Haynes, Eddie Palmieri. You name it. I started to apprentice with him when I was 12 and I started travelling and going on the road when I was about 13. I’ve been doing that for about 21 years now.

BROWN: Did you ask for a trumpet when you were 11?

SCOTT: Yeah. I actually wanted to play the saxophone, but my uncle played the saxophone, and I realized that if I played an instrument that was related to his instrument, it would probably be easier for me to apprentice with him and go on the road. If I played the same instrument, it would be redundant to take me on the road. So I picked the instrument because of its relationship to my uncle Donald. But I hate the sound. Part of the reason why I create my own line of trumpets and all these different types of B-flat instruments is because I fucking hate the sound of the trumpet. It’s terrible!

BROWN: What are the horns you created called?

SCOTT: They have different names. There’s a siren trumpet, a sirenette—which is closer to a cornet—a tilted bell trumpet and the reverse flugelhorn. I have four different prototypes.

BROWN: How did you develop them? Did it start with you literally hammering out the horns you had?

SCOTT: [laughs] No. I started as a little kid; I would take my horns and break them and bend the bells up. I had a big dent in my bell and my mother made me play with it. I was always interested in changing the sound up, but when you don’t have the tools to do that effectively, you can just break the instrument. I learned pretty early on that I shouldn’t do that.

Once I started making my own records, a lot of different horn companies were interested in me playing their trumpets. The first one that I ever created, I made with an American company called Edwards of Getzen Instruments. I was maybe 19. Then there’s a guy that I consider the best horn maker in the world, Miel Adams, and he came to me saying, “It’s really rare to find people who have fresh ideas about what to do with these instruments.” I don’t believe that the guy who created the general shape of the trumpet 200 years ago has a better idea of what sound can do than I do, so I’m like, “Let’s try to figure out a way to create the future with these instruments.”

So yes, I have hammered bells before, I have soft-soldered horns and all of these things, but generally what happens is I will come up with a concept of what I want the shape to be, because I know what certain turns will do—what will darken the sound or brighten the sound or make it more pinched. I’ll sketch what I want, and then my identical twin brother Kiel [Adrian Scott] will sketch them out and make them completely accurate. We’ll send that to Miel, and then he’ll start to put the hammer to the metal and try to build them.

BROWN: What made you decide to pick up an instrument at 11?

SCOTT: I boxed. I was a really good youth boxer, and I enjoyed the sport very much. Once I actually started to play the trumpet, it is very similar to boxing. Most of the great trumpet players boxed: Miles Davis was a boxer, Wallace Roney is a boxer, Terrence Blanchard is a boxer. In a boxing ring, no one can help you. It’s just you and the other guy, and your job is to get him out of there, to outscore him in the best sense of it. When you learn to box, the first thing they teach you is to protect yourself at all times, and some people also learn that they like being hit.

The trumpet is a very violent instrument—probably one of the most archaic of all the modern instruments. It’s physically really demanding: you have to stay in pretty good shape. Historically, some trumpet players get what we call “trumpeter’s belly,” so it seems as though they are out of shape, but they’re not, it’s just because their diaphragmatic muscles have to be able to expand to really play the instrument. So I have to work out all the time. I have a regimen where I’m in the gym every day and I jump-rope at least 45 minutes to keep my air up. It also hurts a lot: it cuts you, it bites you. The better you get, the more it hurts, and no one can help you manage it. It’s just you against the machine, essentially, and that facet of it I really liked.

I liked it because it’s related to boxing, but also it has a capacity to create a different type of beauty. There are fight fans, people who want to see that, but what they’re really there to see is pretty rough. They’re there for blood, which is fine. It’s part of it. I enjoyed having the same type of internal, mental, physical fight, but enduring that sort of trauma or pain to send a message of love. I can still have the fight, but what I’m fighting for is more a reality that I want to create.

BROWN: Do you ever play to relax?

SCOTT: It doesn’t relax me. When I play, my mind turns on. If I touch that instrument, everything starts.

BROWN: What was it like growing up in New Orleans?

SCOTT: In New Orleans, a large part of the populus considers themselves Afro-Native American—Black Indian—and my grandfather is the only guy to be the chief of four different tribes of Black Indians. I actually became Chief this year. It happened a few months ago. My tribe is called the Yamasee or the Brave. In New Orleans, you don’t use the old tribal affiliations. It’s kind of a complicated story, but they adopted new names in English, so my grandfather was the chief of the Brave, the Creole Wild West, the White Eagles, and the Guardians of the Flame. That’s the one I was born into.

BROWN: What does being Chief mean?

SCOTT: It’s a lot. The first charge is for you to create an environment and a space of welcome for the community. In the older system, sometimes you settled accounts for the neighborhood and that type of stuff. But my family has a non-profit for culture retention where we have programs that teach children everything from West-African rhythmic retention to fiscal literacy. We have a standard literacy program, and last year we gave away 44,000 books to kids in the 9th Ward. It really becomes about being immersed in the community and being a presence—letting the people in the neighborhood know that there is someone there that will do whatever they need done, essentially. Whether it’s sitting in a city council meeting and starting fires in that way, or rubbing elbows and shoulders with people that are elected officials in the municipality.

BROWN: Young professional horn players seem like quite a rare thing to me, but was it very different growing up in New Orleans?

SCOTT: Oh, yeah. In New Orleans, you can pitch a rock and hit a great trumpeter. [laughs] But it’s also one of the few ways that a lot of people from the inner city, historically, can build resources. Louis Armstrong is from New Orleans and the airport in New Orleans is Louis Armstrong International. If you come up in New Orleans, the captain of the football team is not popular; it’s the bandleader or the drum major or the section leader. They know that these kids have access to resources when they grow up, whereas if you play football, what are the chances of that?

BROWN: When did you realize that you were a good enough musician to pursue it professionally?

SCOTT: To me, music is always about communicating first. What we do at Stretch Music is really more of reevaluation of what we communicate in this culture of music. When you say “good enough,” there’s different layers to that. Someone can be really proficient on an instrument and play pretty much most of the things that you can play on an instrument, but not be a good communicator, so to me they’re not very good. It becomes, “Why are you practicing? Why did you practice 10,000 hours if when you play something no one can relate to it?”

To me, trying to achieve the balance is when you become good: when you have enough technique to be able to play what is that you want, but also when you can refine what you want to communicate to people. As a younger person, it wasn’t something I thought about so much. I practiced so much and my environment was telling me that people who could do it at a high level respected me as a young person and wanted me to be in an environment where I could get better. I kind of concluded that I could play. I would never have said that, but when you’re 13 years old and the Preservation Hall [Jazz Band] is like, “Come to play,” you probably can play. [laughs]

BROWN: What was it like when you started touring professionally? Where did you go?

SCOTT: The first band I played in was my uncle’s band. He has a concept of music called “Nouveau Swing,” which, at the time in the ’90s, was a completely new approach to rhythms. A lot of what we’re doing now is derived from that, and that’s how I learned to play. It was an incredibly popular band, and he was an arrestingly handsome guy, so my introduction to the road was with him. We’d go to Japan, Portugal, Brazil, Colombia, Australia—all over.

BROWN: Were you the youngest person in the band?

SCOTT: I was always the youngest person. Now I’m starting to be the old guy. It’s cool; I like it. But I was the youngest person for like the first 15 years of my career. I was in an environment of 40-year-olds.

BROWN: Would you go out with them after shows? Or did you have to go home?

SCOTT: Sometimes. Sometimes it turned into a completely different thing where they’d be trying to teach me things. [laughs] Some of the things that I learned on the road were helpful and some of them were terrible things that I would never, ever teach that to younger people. The road’s a rough place for kids, but I did learn a lot. I became everyone’s favorite pet thing, because it would make it easier for [the other players] to get girls if I was there. They knew that. I didn’t know that. I was just trying to get information about music. [laughs]

BROWN: When did you start making the music your own?

SCOTT: I think that happened pretty early on for me. They call what we do “stretch music.” This is our style, and one of the newer, in vogue ways of playing creative, improvised music. It really grew out of me trying to address something that I saw in my everyday life in my neighborhood—trying to develop that and refine that and excavate exactly what that was in a way that, when I communicated it, it was palpable and easily read. That started really early. Why it started was from something that I was really angry about.

I’m from New Orleans, I grew up in the 9th Ward, and across the street from my house is William Frantz Elementary School. William Frantz is the first desegregated school in the Deep South; it was desegregated by a little girl named Ruby Bridges. There’s this beautiful Norman Rockwell painting [“The Problem We All Live With”] of her walking, and someone wrote “nigger” on the wall and people are throwing tomatoes at this baby… It was interesting neighborhood, even in the ’80s, when I got there. First it was a white neighborhood, then once she desegregated the school, it became inundated with blacks. There was a certain flight, but some people that were there preceding blacks coming in didn’t leave. So then they had blacks and whites in the same space that viewed each other as nemesis, but were essentially going through the same realities.

As a kid, this was very fracturing and confusing to me. I would see black families that were food insecure and white families that were food insecure; black families raising children that were being undereducated so they could be in the labor class, and white families going through that. They were having the same experiences and living in the same spaces, but because of these old-world notions, it was an adversarial thing. As a young person, this bothered me a lot because I could feel there was no merit for it.

I’m sure that you and I will agree that, insofar as it is a social construct, race exists, but it doesn’t exist—there is no “homosapien Afrikaans.” At some point we were all together. Your ancestors may have taken a different route to get to where you are now than mine did, and you look a little different, but that doesn’t mean we’re two completely different species. When I was a kid, I was looking at this and trying to figure out a way to musically address this fracturing. I was seeing my friends that have profound love for each other, once they were 13 years old, not really fuck with each other because they look different. Part of I wanted to do as a young person, and what we’re doing now, is to try to eradicate this limited notion of how people are interacting with each other through hyper-racialized ideas. A lot of it dealt with, as an example, genre. If I ask you to visualize a trap musician or a hip-hop musician, you’ll see one thing. If I say visualize a western classical musician, you’ll see a very different thing. A lot of how music is disseminated to us is hyper-racialized. It’s not something that we think about all the time, but if you take a minute to look back, it’s why you get this argument when there’s a white rapper—

BROWN: And why you say “white rapper” in the first place.

SCOTT: Exactly. In a nutshell. To me, these ideas are really limiting. Anyone should be able to express themselves in any context. Obviously, there are arguments against appropriation, but it’s one thing when someone is doing something for satire or making fun of a culture, but if they respects the tenets of the culture and they want to be a part of that, what could be more beautiful than that? If you look at music and say, “All of these different genres are hyper-racialized,” then one of the ways I can creatively address the problem is if I can show that I can marry seemingly disparate cultures of music. If I can take traditional Japanese music and mix it with the tenets of Polish folk songs, and mix that with rhythms from Senegal or Mali, and then mix that with the sonic palette that you might hear in trap music, then what am I saying about all those people? Creating an environment musically that shows that we all belong together is what I’m interested in doing, and that happened really early on.

BROWN: And it’s still your driving force?

SCOTT: I don’t think it’ll ever change, until this changes. I think there are a lot of people that consider themselves fusionists, but they hold pejorative and belittling ideas about other cultures of music. I genuinely respect the other forms of music and the people that make it.

FOR MORE ON SCOTT, HIS TOUR DATES, RULER REBEL, DIASPORA, AND THE FORTHCOMING EMANCIPATION PROCRASTINATION, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.