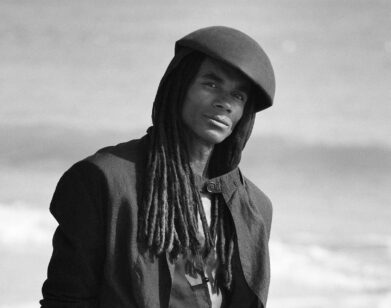

Chet Faker, Behind Glass

ABOVE: CHET FAKER IN NEW YORK, APRIL 2014. PHOTO: CHRISTOPHER GABELLO.

Tomorrow, Nick Murphy, or “Chet Faker,” will release his first solo album, Built on Glass. Thanks to a viral cover of Blackstreet’s “No Diggity,” however, the Australian musician has been a public entity for over two years. He’s released an EP and an album with fellow Aussie Flume, had his “No Diggity” play in a Super Bowl commercial, and is about to move from Melbourne to Brooklyn. In demeanor, he is far from the green, excitable newcomer we met on the day of his eighth-ever show in March of 2012. As Murphy notes, “a lot” has changed. ” I’ve done more than eight shows now,” he laughs. “I stopped counting sometime last year.”

“There’s a lesson I’m learning right now,” Murphy continues, “which is, if you write really personal songs, people are going to ask you even more personal questions about them. Some person was like, ‘What’s the story behind “To Me.”‘ It’s the most fucking personal song on the record—I’m not answering that. I’m not a jukebox.”

Influenced equally by his mother’s Motown favorites and his father’s “chilled-out Ibiza CDs,” the strength of Murphy’s songs lies in their restraint; a subtle beat anchoring soulful lyrics. In “To Me,” Murphy’s voice feels like it’s constantly on the verge of breaking—there is so much emotion as he sings “When you curl up in bed/And it’s you in your head” and ends with a clipped “Are you livin’?”—but you have to choose to engage with it.

EMMA BROWN: Built on Glass features a song with with Kilo Kish, “Melt,” and you’ve worked a lot with Flume in the past. When you’re collaborating, do you generally work via email or are you in the same room as the other person?

NICK MURPHY: It changes. It depends on how accessible they are. I’ve never actually hung out with Kilo in the flesh—I’ve spoken to her on Twitter and stuff. But with Flume, we’ve done both: we went away and spent time in the studio, and we’ve done via email as well. You can’t always get studio time. [Our first collaboration] was all via correspondence, and then we met.

BROWN: Is it awkward to meet someone in person whom you already have this email relationship with?

MURPHY: I guess so, but this whole industry is awkward; I just met you and I’m telling you personal things about my life. But that’s my life: “Hey, how you doing?” [laughs] There are not a lot of people that you can relate some of these things to, so it’s nice when you meet someone who is going through similar stuff—not “going through,” but that “gets” stuff like that. With Harley [Streten, Flume], we both started around the same time. We’ve had a reasonably similar trajectory; obviously he’s a bit bigger.

BROWN: Have you ever tried to work with someone and you like their music, and they like your music, but for some reason, it just doesn’t work?

MURPHY: Yeah, totally. That happens a lot. That’s why I think it’s really important to not talk about how you’re going to release something until you’ve finished it. People are like, “What are we going to make? What are we going to do with it?” and it’s just like, “I don’t know, we’re just making music. Then we’ll talk.” You can’t always write something you’re happy with; you can’t force it. I’ve done a bunch of collaborations [where] it goes well and you finish it, but then you’re kind of like, “I just don’t like it.” And it sits there. It can be awkward, but a real musician understands that you’re not always going to make what you want it to be. You can’t just polish everything into perfection. So sometimes you’ll make something and you’re just like, “That didn’t work, we’ll try again.”

BROWN: And the other musician generally feels the same way?

MURPHY: They should if they’re professionals. Sometimes people can get shitty, but you won’t last in that industry by taking things personally. It gets awkward when you’ve done three or four things and it still isn’t working—then it’s like, “Oh, maybe we just shouldn’t work together.”

BROWN: Is it hard for you to choose between edits of a song?

MURPHY: It’s not hard; I do lots of different ones, though. That was one of the best things I ever did with my work process: you save two versions of it. Sometimes you can be afraid to touch your own artwork because you don’t want to fuck it up, which is so dumb, but it happens when you put lots of work into it. So because it was on the computer, I could save a project and then open another one and just fuck with it. I’ll often have four or five different alternate versions of a song. It’s usually obvious which one is the best one, but sometimes they just become totally different songs. Like “To Me” used to be way, way faster; it wasn’t a slow ballad at all. It actually reminded me of MJ’s “The Way You Make Me Feel.” But it didn’t fit the record, so I slowed it right down.

BROWN: How much time do have to celebrate releasing your first album before you start thinking about what’s next?

MURPHY: No time at all, really. I had maybe a week last year when I finished it. Because this is a production studio project, I have to learn how to pay it live. I’m not sitting there writing it with a band—I’m writing it myself. So it’s like, “Yeah, I finished!” and then, “Fuck, now I have to build a live show.” Then I have to go on tour, but I’m not complaining. It’s what I want.

Today, technically, the album came out for the first day somewhere in the world. That’s pretty cool. I try really hard to not get excited about anything these days, because you never know if something will happen. But it is cool that my album is coming out now. You only put one first album out, so I’m trying to enjoy that.

BROWN: Are you going to go to a shop and buy a copy?

MURPHY: Buy it? No. [laughs] I’ll buy the vinyl, but then what if someone recognizes you? “What are you doing? Doesn’t your label give you one?” and you’re like, “Oh… I don’t know.”

BROWN: Just tell them you wanted the experience.

MURPHY: Well, my mum texted me yesterday with a picture and she said she bought four of my CDs.

BROWN: That’s sweet. What was the hardest song to translate live?

MURPHY: I haven’t done them all yet, so I don’t know. [laughs] I do lots of backing vocals, and I can’t do that, obviously.

BROWN: Are you going to get back up vocalists?

MURPHY: I can’t afford back up vocalists; they’re so expensive. Because I’m independent—I’m not signed to a major label, which a lot of people don’t know, and it doesn’t matter anyway. I can’t just have an eight-piece band touring. One day—definitely. That’s like a goal. It’s my first album, I’m trying to do a slow build. If you do all the bells and whistles straight off it’s like, “Where do you go from there?”

BROWN: Cost affects art in ways you would never think of. I’ve talked to playwrights who will cut down the number of characters in their play because of the cost of hiring another actor.

MURPHY: Seriously. I produced the record, I engineered the record, I performed every part, I wrote every song. Yeah, “I did it myself and that was important to me,” but I didn’t have an alternative. It took me two years; people would have no idea how much it would cost to spend the amount of time I spent in my studio in a real studio for two years. The whole record kind of talks about it. The metaphor of glass has a bunch of references, but one is a glass frame: taking something that might be mundane and normal but, by placing a glass frame in front of it, you direct attention to it. You can turn something into art just because of the way you tell people to look at it. This album is my life, and my life’s really not that interesting. It’s not “not interesting,” but I’m just some dude just like everyone else. But by recording it in an album format, it becomes a product. [That’s] the idea of Built on Glass; it’s the relationship between my personal life and the music I make. It’s obviously very personal, but it becomes this product at some point, but, at the same time, it has nothing to do with anyone else.

BROWN: When does your work start to detach from you?

MURPHY: Usually, as soon as it gets released. Really, when anyone else listens to it has nothing to do with me. My album to me is something, but anyone who buys it, it’s whatever it is to them. I don’t like telling people what specifics are of the record, because that could ruin it as an experience for someone else.

BROWN: Is it something that you learned through releasing music?

MURPHY: I definitely learned over the last couple of years. You don’t even think about it—well, I never thought about it.

BROWN: Can you dance?

MURPHY: I’m totally getting into dance at the moment, but no, I can’t dance.

BROWN: Why are you getting into dance? Aside from the amazing dancing in your “Drop the Game” video with Flume.

MURPHY: Yeah, Storyboard P? He’s the man. That actually had a lot to do with it. All of my friends are really good dancers, which was initially why I never danced—we’d go out and they would kill it and I’d be like, “Yeah, I’m just gonna sit at the bar.” I broke my foot a year and a half ago now and I couldn’t run for a year, but I realized I could kind of dance. It reminded me how amazing dance is; it’s so in tune with music—it is music. It’s a physical expression of whatever music is. I spend so much more time on stage now and so much more time physically interacting with music. When you’re in the studio, it’s all in my head; I wouldn’t even know if I move or dance when I’m recording because it’s just me in there. But on stage, you’re interacting with things—physical things. So I’ve really started to like and notice the way people move with music.

BROWN: Do you think all music is danceable?

MURPHY: No way! I think you can move to everything, but with some music you just want to sit still. That’s me anyway. Like Debussy—I couldn’t dance to that… [laughs]

BROWN: Do people ever recognize you?

MURPHY: Yeah. Absolutely. The beard is a curse.

BROWN: Really? Everyone has a beard in Brooklyn.

MURPHY: It makes me think about how many people get mistaken for me. On my Instagram, lots of people tag me in photos of just dudes with beards and they’re like, “Oh my god, I met Chet Faker” and I’m like, “That doesn’t even look like me.” I posted one the other day. I feel like I’m experiencing beardism or something. [shows picture] Not even close. But look how happy they are.

If people come up to me, I’m going to be nice to them. Essentially, the assumption is that they support what I do. If I met someone I’d be like, “Hey, I respect your art or your work,” and then that’s it—let’s not go beyond that. But sometimes people are like, “What’s going on, man?” “I’m on the street, and we’ve never met before.” [laughs]

BROWN: I never go up to people at all because I feel like they must hear it all the time.

MURPHY: I rarely do. I think the only person was Four Tet and Caribou, and that was the most awkward shit ever. I had to tour with Bonobo and I love his shit—I’ve loved it for ages—but then we’re hanging out and he’s asking me about music and we’re just chatting as equals. That’s one of the weirdest things I’ve had to do: reassess someone that I looked up to [and], all of a sudden, have to look at as a peer. They’re the weird moments where I pinch myself.

BUILT ON GLASS COMES OUT TOMORROW, APRIL 15. FOR MORE ON CHET FAKER, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.