Charlotte OC Comes of Age

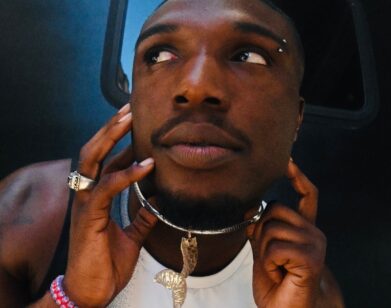

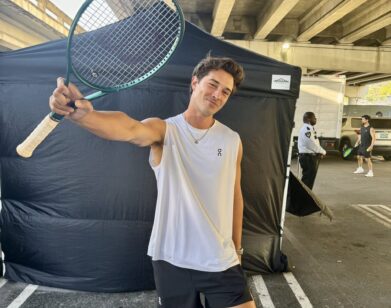

CHARLOTTE OC AT THE ROOST COFFEE & SPIRITS IN NEW YORK, FEBRUARY 2017. PHOTOS: MICHAEL SCHWARTZ FOR ATELIER MANAGEMENT. STYLING: OLGA YANUL. HAIR: MARTIN-CHRISTOPHER HARPER FOR PLATFORM|NYC USING GHD. MAKEUP: HOLLY GOWERS FOR ATELIER MANAGEMENT USING CHARLOTTE TILBURY. PHOTO ASSISTANT: AMANDA YANEZ. STYLING ASSISTANT: MARINA DYMNICH.

“I was definitely turning into a young woman from a girl,” says Charlotte O’Connor of the two years she spent working on Careless People (Harvest). Released on Friday under her moniker Charlotte OC, it’s the first full-length album from the 26-year-old British artist, who has matured as both a songwriter and musician since her 2014 EP Strange. She shifts seamlessly through an array of genres, including electronic, R&B, and gospel, using her soulful voice to carry the listener through what she considers her “own little time lapse.”

“I’m still in touch with how I felt,” she says, reflecting on the emotions that fueled her writing. The songs on Careless People mean more to her now than when her pen first hit the page, but O’Connor is already looking ahead, and sees them as a “stepping stone” in a new direction. When we speak to her by phone, she is at home in London, recovering from the flu and preparing for the album’s release. As she explains, completing her debut frees her to move forward.

HALEY WEISS: I’d like to talk about the title of the album, Careless People, and how you arrived at it.

CHARLOTTE O’CONNOR: I was watching The Great Gatsby and it hit home. I’ve read the book, but when I was watching it, I got really pissed off at Tom and Daisy because they just whooshed Gatsby along in this massive whirlwind, and then, in the end, when it all just got a bit too much for them, they ran away, and Gatsby ended up being left to cope, and then he died. I feel like that happens so much in life, where if you get whooshed up into this certain situation, it can feel so good to you, and could mislead you into thinking that the other person is amazing, and then they all disappear, and you’re left to pick up the pieces. You’re left to process it. I think when I was making the record, I was doing that to somebody and then somebody did it to me. I feel like that’s where I was at and I connected with it. It annoyed me because I was like, “I know exactly how that feels.” I just fucking hated them for it, and I hate myself for making anyone else feel like that. The album is a portfolio, if you will, of moments where I was carrying a bit too much bad stuff; moments where I probably should have cared less about some things; and moments where I was careless with myself, with other people, and their emotions. That’s why I named it Careless People.

WEISS: When we interviewed you back in 2014, you talked about wanting to make music that’s “more live, organic, and timeless.” Is that something you think you achieved in making this record?

O’CONNOR: Definitely. The end of the record, with songs like “In Paris,” “Where It Stays,” “I Want Your Love,” and “Higher”—that was all done in Sunset Sound [recording studio] and all full band, live vocals, and stuff like that. In the beginning, I wanted it to be a transition. I didn’t want it to be too far away from what I’ve been doing. I feel like I did get that in the end.

WEISS: If you see this album as a “stepping stone” to other sides of you, do you feel like after releasing it you’ll have the freedom to step further into a different direction?

O’CONNOR: Oh, yeah, I can’t wait. I’ve already started. I think about it non-stop. I don’t know where I could go, but I know that lyrically, I have a lot more to say. I think that’s what’s exciting about getting the first one out of the way, but it’s also really scary and daunting—trying something new.

WEISS: You’ve said that you think you grew from writing “Darkest Hour.” What about it was challenging and affected you?

O’CONNOR: The lyrics, the story behind it is quite delicate, and it’s still a delicate subject. It was about putting that across without it pissing off the person I wrote it about, and it being done in a sensitive way and in a way that’s not aggressive. I didn’t want it to be giving the listeners exactly what they wanted, either. Leonard Cohen was a massive influence in lyrics and the way that he tells a story, and I wanted it to be like that, because he really gets that haunting, gothic vibe. He’s got it down to a tee. I took inspiration from that, but it was like treading on eggshells with the subject matter.

WEISS: Is that something that’s important to you generally when you’re making music, that you’re being sensitive to the subjects you’re writing about?

O’CONNOR: Not really. I don’t really give a shit. [laughs] But with that one especially, it’s my sister and it’s family. It’s got to be real, and I didn’t want it to only be one side of the story where it would make her feel uncomfortable and people think, “Well, that’s your side of the story.” I needed it to be honest. I didn’t want it to come across like I was saying, “You’ve been a dick. You put yourself through shit. What an idiot.” So it was challenging, but of course I [still] felt like that.

WEISS: In terms of the Leonard Cohen influence, he also wrote poetry. Do you write poems that you don’t intend on making into songs or are they always written as lyrics?

O’CONNOR: I never write poetry. Somebody asked me a question the other day: “If you would like to learn how to do something, what would it be?” And I said, “I’d love to write poetry or paint.” They’re two things that I don’t do at all and find really difficult to do. I do write stuff down—mostly on planes. I’m really emotional on planes. I think most people are. I usually end up writing while crying over a glass of gin and tonic or wine. [both laugh] I watched this girl watching Toy Story 3 on the plane. It was the biggest faux pas I’ve ever seen—she was hysterical. She was all alone and it was so cute. She couldn’t stop crying because of the altitude. I get like that on planes, but I still doubt I’m writing poetry if I’m doing that.

WEISS: Are you self-critical?

O’CONNOR: Yes, very much so.

WEISS: How do you get past that to allow the creative process to happen?

O’CONNOR: I find it quite difficult, but that’s why I have people around me that are supportive or can see when my things start working in times when I don’t. Which is annoying, because I shouldn’t feel like that. I get shouted at for feeling like that, but I just do.

WEISS: You’ve talked about how some of the songs on this record are quite personal and emotional, but you don’t always write from your own perspective; you’ll write when you overhear something or if you’re told a story. You also, at one point, said you worked at your mom’s beauty salon washing hair. I wonder if there are any stories from that time that you heard and made into songs.

O’CONNOR: Yes, totally. I remember when I was younger, it wasn’t necessarily that I used to write songs, but I used to see these clients come in, and whenever you get your hair done, they always open up to the hairdresser—because you’re touching them, so they feel like there’s a maternal instinct, you feel like you’re being mothered. My mum would hear all these stories and as a kid, I used to be like, “Oh my god, I can’t wait till I’m older and I can feel stuff and be heartbroken so I can actually write something about it.” I loved listening to all of these stories and I’d be mesmerized by it, about pain, about boys, and about heartbreak, and I’d think, “Oh my god, how could they even like boys? Boys are gross.” I was fascinated by it, and I think I still am a little bit. I keep getting reminded in interviews that I said I couldn’t wait to get my heart broken so I could write about it, or something like that, and I still feel like that. Well, maybe not so much—I know what it feels like to get your heart broken now, and it’s fucking horrific, I wouldn’t [want] to do that again. But to make really fine art, I think you’ve got to feel horrific stuff, and I couldn’t wait to feel that.

WEISS: How old were you when you were working at the salon?

O’CONNOR: That was when I was about 15. I only lasted a week. My mum fired me because I was rude to everybody. [laughs] But when I used to listen to clients, I used to go there after school every night, that was when I was six or seven. I used to love listening to all of the problems. But yeah, I got fired. I was rude to everyone. I was talking to my mum about it. I’m quite a social person to a certain point, and then all of a sudden I want to run away and I don’t want to talk to anybody, and I’m still like that now. I’d become really quite introverted, and I suppose that’s not good when you’re a hairdresser or working anywhere dealing with the general public, because you’ve got to be on it constantly. I wasn’t the best.

WEISS: You were dropped from your old label Columbia as a teen, and they basically told you that they didn’t know what to do with you. Now, looking back, how do you feel about that time? Was it that you were still finding yourself?

O’CONNOR: Totally. I didn’t know what to do with myself. I think that’s the whole thing. If I don’t know what to do with myself, why would anybody know what to do with me? I guess I knew that when I was 18. I was so young. It was crazy. I don’t think you should be in the music industry that young. It’s mental that I would even be doing it at that age, and that I would be deciding what things should be and deciding who I am at that point. I’ve only just figured out who I am, and I’m still learning, and it feels much more beautiful now than it would have when I was younger. It’s so nice to do these interviews and feel like I’m saying what I’m saying with some conviction, because I’ve worked hard at it and I know what I want to say. Back then, doing interviews, even doing photoshoots and stuff like that, there was no identity. I just didn’t believe it. I was on a bit of a holiday and thanking my lucky stars I didn’t have to go to uni. [laughs]

I don’t look back on it and regret it because it’s almost like an apprenticeship. I was learning, and I was lucky enough to be signed and realize what it’s like to be on a label that you don’t want to be with, and what it’s like to be with a label that’s telling you to be a certain thing. If that ever happened to me now, I’d be like, “You can go fuck yourself.” I know not to stand for that. But at that age? I was at the right age to be told what to do, because I did not know what was going on. When you turn 25, I feel like you’re more present and you’re more alive, and I feel like that’s just happened. I was freaking out being on TV not long ago, when I did the Seth Meyers show [Late Night with Seth Meyers]. That freaked me out because I was like, “Oh my god, people. I’ve got nothing to hide behind.” People saw me for who I was. I had no control over that. Imagine doing that when you’re 18 and not knowing who you are.

WEISS: Does that feel freeing? Knowing who you are and that there is no barrier?

O’CONNOR: Yes—very vulnerable, but very freeing, because it just is what it is. Deal with it. [laughs]

CARELESS PEOPLE (HARVEST) IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON CHARLOTTE OC, VISIT HER WEBSITE.