in conversation

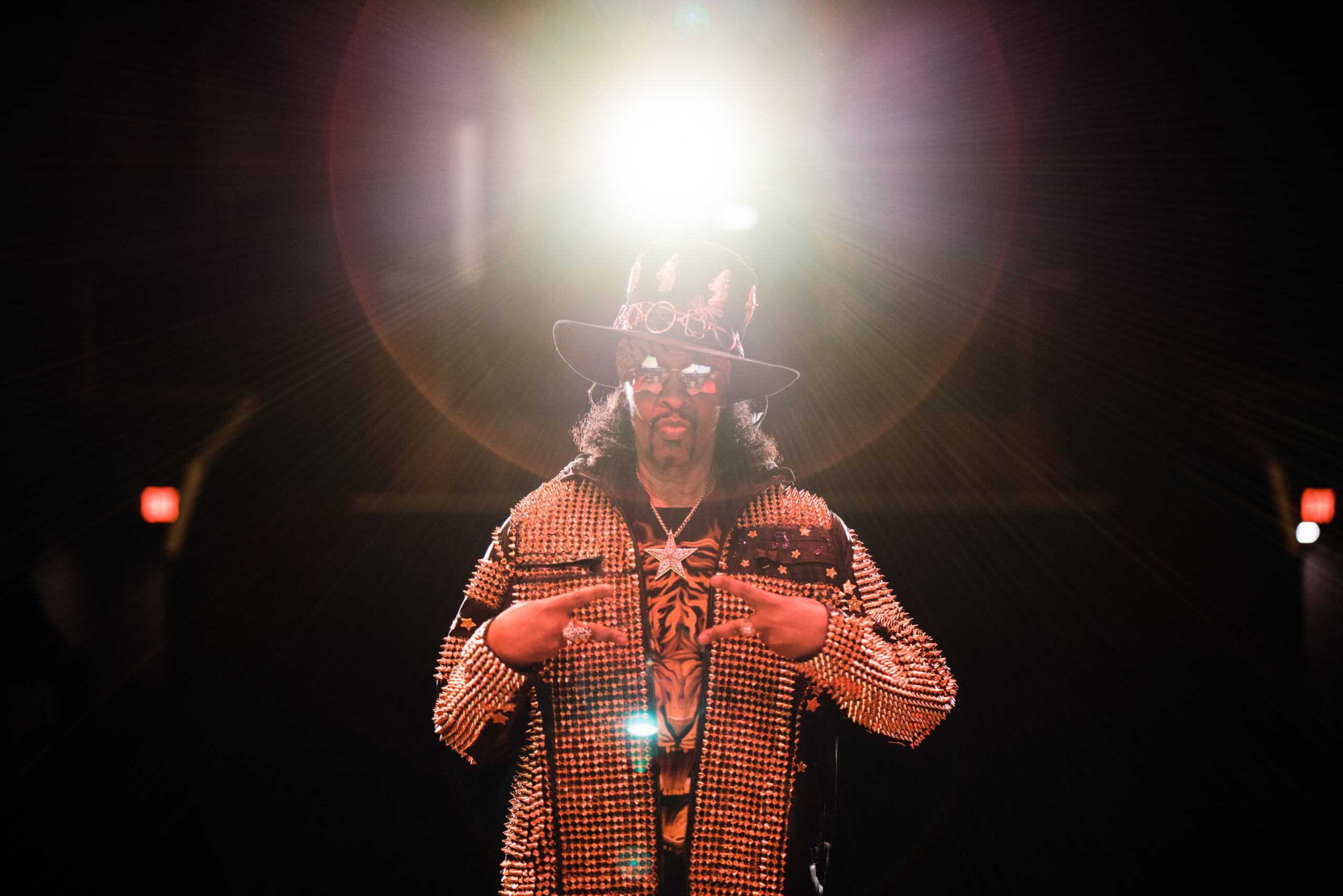

“I Don’t Ever Want to Grow Up”: Bootsy Collins and Matt Berninger on Freedom and Legacy

Photo by Michael Weintrob.

Bootsy Collins puts the “fun” in funk. His music consistently infuses pulpy melodies with infectious charisma that just make you want to move. With a career spanning nearly five decades, Collins continues to sound fresh and innovative. He defies categorization; over the years, he’s worked with everyone from James Brown to Kali Uchis. His influence is most noticeably seen in Childish Gambino’s “Redbone,” which pays homage to Collins’s 70s hit “I’d Rather Be with You.” In keeping with his habit of surprising collaborations, his latest album, titled The Power of the One, brings together artists and thinkers such as Snoop Dogg and Dr. Cornel West. In honor of his new project, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame legend hopped on the phone with fellow Cincinnatian Matt Berninger, the lead singer of The National, who also has a new album out titled Serpentine Prison. The pair discussed Ohio’s musical legacy, James Brown, and why growing up isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. —JULIANA UKIOMOGBE

———

MATT BERNINGER: Hi, Bootsy.

BOOTSY COLLINS: How you doing today?

BERNINGER: I’m actually pretty good. I’m in California. It’s sunny and nice. Where are you?

COLLINS: I’m in Cincinnati, Ohio. You know, one of your homies.

BERNINGER: I miss it. I haven’t been there in a little while. What’s the vibe in Cincinnati?

COLLINS: As far as the weather, you just never know from day to day. It’s cold then it’s hot. As far as musically speaking, you know how Cincinnati is. It’s very conservative. But downtown was opening up pretty good before COVID hit. People had started to come back down, but everybody’s struggling now.

BERNINGER: I wanted to talk to you about Cincinnati as a place and as a really healthy musical place. I did leave the city to pursue things in New York and now here in L.A., but I always thought Cincinnati was incredibly fertile. There were so many venues and bands.

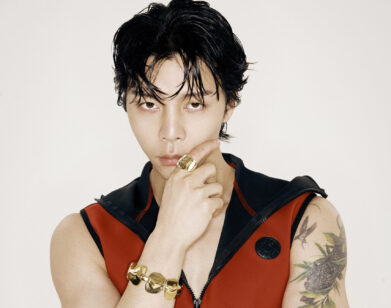

Photo by Chantal Anderson.

COLLINS: To me, it was probably one of the best places to grow up, especially if you were into music, because you had just about every kind of music there was. You had all the clubs. Coming up back in the day, everything was pretty much available and everybody was into it. We were out there going to different places and getting gigs. It was a great experience musically, and we had fun doing it. That’s the reputation of Cincinnati. King Records, which we’re involved with now, is the blueprint of Cincinnati because it engaged and embraced all genres of music. Everybody just did their thing. That’s how the city developed musically.

BERNINGER: My band The National is from there, but I know so many different bands like The Breeders and Guided by Voices around that area—Southern Ohio and Cincinnati specifically. There’s a really fertile cross-pollination of lots of different music genres. It was there when I was first dipping my feet into going to see stuff at Bogart’s and Sudsy Malone’s. But I was always wondering, how did Cincinnati get such fertile soil? I know with traveling bands going from Chicago, to this place, to New York, it’s a stop-off. It’s geographically a spot where you got to try to pick up a gig on your way to New York or Chicago or Detroit, so that’s how it kind of started, right?

COLLINS: Yeah. You had all kinds, all breeds. Everybody stopped through here, and a lot of people stayed. Starting off, it was just no limits. Nobody could tell you that you couldn’t put jazz with funk or you couldn’t put rock with blues. People just took chances and did things. It’s real difficult to explain it, but it happened. I’m just glad to be a part of it, and I’m glad I had a chance to experience that side of it, because if you don’t get a chance to experience it, it’s like watching a movie as opposed to being in it.

BERNINGER: Yeah, I feel you. It’s a conservative city, but there is a really healthy, progressive, artsy, strange side. If you want to, you can find a group of people that are up for anything artistically.

COLLINS: It was a lot of what I call “inside rebellion” going on. It was a really conservative city and everything, but I think inside, there was a whole lot of rebellion. It just wasn’t as loud as other places. Now everybody’s like, “Wow, we didn’t know Cincinnati was like that.” They’re getting a look for the first time, but it’s been like that.

BERNINGER: I wanted to talk to you about when you started a band with your brother in the late ’60s, and then the two of you worked with James Brown and then eventually with Parliament. When you left Cincinnati, you started broadening your horizons. How did you evolve into what you are now?

COLLINS: Wow, I think for me it really started when I got my wish of playing with my brother Phelps. That was the biggest hurdle at that time. How do I get to play with my older brother? Older treat younger brothers like dirt. He didn’t want to have me around, but the band that he always rehearsed with loved to have me around because I was always excited to watch them play. I didn’t ask for nothing. I just wanted to watch rehearsal. My brother didn’t like when I was around until one day he needed a bass player. Of course, I didn’t have a bass. I had a guitar. But I explained to him that if he got me four bass strings that I would put the bass strings on this guitar and I would be the bass player for that night. That was the night that started everything. The thing that got me wanting to be a musician was when I had to play at King Records and we became studio musicians. We met Gene Redd who was one of the top A&R engineers over there. Henry Glover, who produced all the bluegrass, the country, the R&B, gospel, was producing everything over there. He got us to do all these records. Out on the road with Hank Ballard was the first hooked-up gig that we did with James Brown. I guess at the time James Brown was trying us. He was testing. We had no idea he was testing, because maybe later on like, “Yeah, we might be in his band,” but we had no idea it was in his mind. Sure enough, as a year went by, a year or two, next thing we know, we get a call from Bobby Byrd and, “James Brown want y’all to come on down to Augusta and play the gig.” We thought we were going down to open the show, because that’s what we were doing, playing behind his opening acts. But little did we know, he wanted us to be his band. We didn’t find that out until we went. He sent his jet to Cincinnati, Ohio with Bobby Byrd. They picked us up at a club. We went from the limo to the Learjet. Man, explaining that whole story in sentences, you really can’t do it.

Photo by Nick Presniakov.

BERNINGER: I know. You reinvented yourself so many times. One learning experience, one opportunity, one Learjet leads to something else. All along the way, you’ve been in so many different bands and collaborated with so many different artists.

COLLINS: Part of the process was was not getting hooked on any one of them. It was more about the experience and the learning process. Like, if I had got hooked on Learjets, I wouldn’t have been able to come from James Brown and go to riding in cars with Funkadelic. I wasn’t stuck on none of the stuff which artists usually get stuck on. Even the really bad stuff musicians go through, I went through it and got through it. You just keep moving. If I’d got stuck on, “Okay, funk music is what got me recognized,” but that don’t mean I don’t love jazz, I don’t love rock, I don’t love heavy metal, I don’t love country. I tip my hat to the experiences and not me, per se. It was about learning this process. “Where’s this going to take me?” That is what was more important to me. That’s what kept it more interesting and fun.

BERNINGER: I love that. When you talk about being stuck and then the process, I think that is what is the central motivating thing for any artistic soul. When someone feels like they can define you, that still can quickly feel like a leash or a box. That makes it hard to learn a new process. When you’re stuck with the same box, you don’t discover anything new, because you’re not in any new water, meaning you’re not with new people challenging yourself. And so, I think with art, everything you just said made it really resonate. If you’re scared of what kind of art you’re making, that’s such an invigorating feeling because at least you’re not on a leash, you know?

COLLINS: To me, it means as much as the music… to have that kind of freedom. I never take that for granted. I was put here to give what I got. I didn’t make what I got. That was a gift to me. Musicians didn’t make what they are given. They’re given that talent. It was given to you, so you give that to people, and the people reward you for it. It’s not rocket science. It just feels so good. It makes you want to keep doing it. That’s the magic of what happened in my whole story.

BERNINGER: I’ve gone off and talked about people being water. It’s this idea that if you’re blue water and somebody else is yellow water, you’re going to be a little bit green. You’re both going to be new colors. That’s collaboration. When I say water, you talk about light in a similar way.

COLLINS: Yeah, it’s the same concept. The good thing is they both are one. We are the same thing. For me, that’s invigorating.

BERNINGER: That’s so interesting. I was raised Catholic. I don’t know if I believe in an interventionist god, but I believe in interventionist art, and I believe in interventionist people who are good. I guess I’m like a polytheist or an omnitheist, meaning we are the collective force of wonder and goodness and god and all that stuff. When I started thinking that way, it made me feel more responsible for my actions and more engaged. Somehow, it made me feel like it’s not about getting to the pearly gates, it’s living heaven now and trying to spread heaven now.

COLLINS: To me, it’s very uplifting. Every time I talk to someone or see someone or interact with someone, I know it’s a give and a take. I’m always on the giving side and I’ll always listen. Most people miss the listening part. You’ve got to learn something.

BERNINGER: People keep asking me if music make a difference politically. There have been times where I’ve thought maybe it doesn’t because of how politically disconnected we are. But then I think, well, what if there hasn’t been any of this music? Where would we be without it? I grew up on the west side of Cincinnati. There were very few people that didn’t look exactly like me around me, but it was just about connection. I went to UC. I moved to the campus there. And then I moved to Brooklyn and lived there for 18 years. When you’re just with people, like you say, on the subway or in a studio or in a rock club, all these boxes or ways that we define each other just dissolve. On this record, The Power of the One, you’ve got so many people on it. Your music and your whole personality are always about fun. You just can’t not move your body to your music. It’s so infectious.

COLLINS: Well, I think it stems from all of the stuff that you go through, and you take it out on people or you take it out on the world. The way I made it through was such a blessing, mainly because of my mother. I grew up in a household with no father in it. I grew up wanting to be the guy that takes care of my mother. I learned because there wasn’t nobody volunteering. I just wanted to learn from every source I could. This is not a past-tense thing. I still want to learn. I feel like I’ve been to that mountain when we were peaking as Bootsy’s Rubber Band. I never want to go there again by myself. That world, that fame, that stardom, I never want to be that ever again. If I can be a platform for others, I prefer to do that. I always wanted to be in the band, but never wanted to front the band. For some reason, I always knew that that was the mug that had the target on his back, on his face, and on everything else. It was a curse and a blessing at the same time. That’s something I don’t ever want to be again. I’d rather have people and learn from people. I can learn from a drunk or a person on the corner. It don’t matter. To me, that was my savior—listening and learning. I want to keep that openness. When I stop being a kid is when I die. I don’t ever want to grow up, because I see what happens to grownups. I’m supposed to be one myself, but you ain’t heard it from me.