SOUNDCHECK

“The Internet Is Basically One Giant Cop”: Backstage at MSG With Jack Antonoff

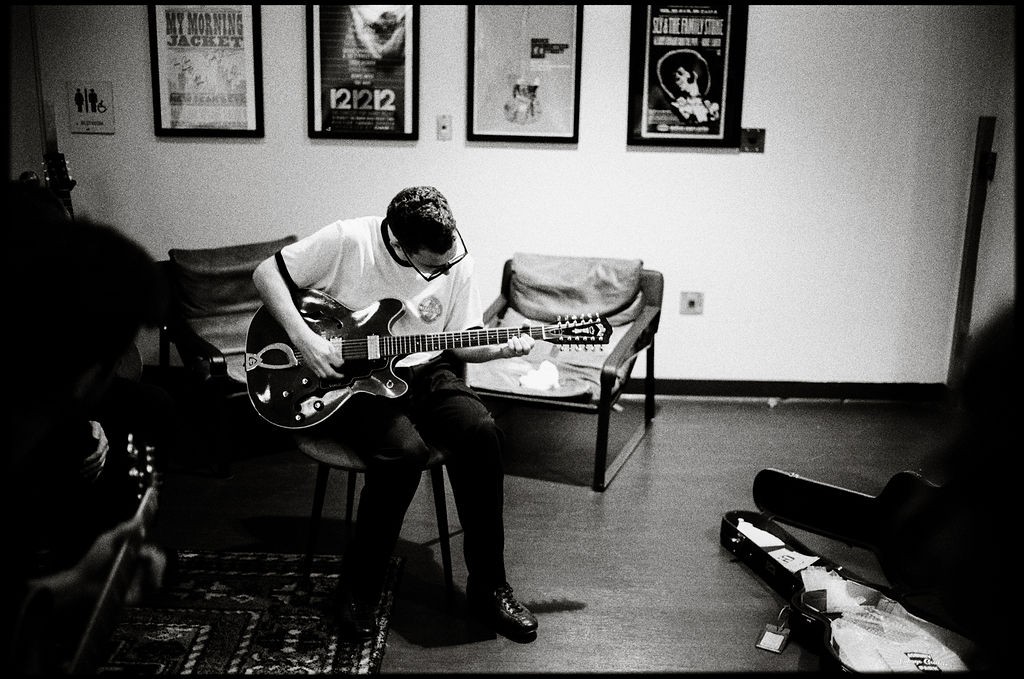

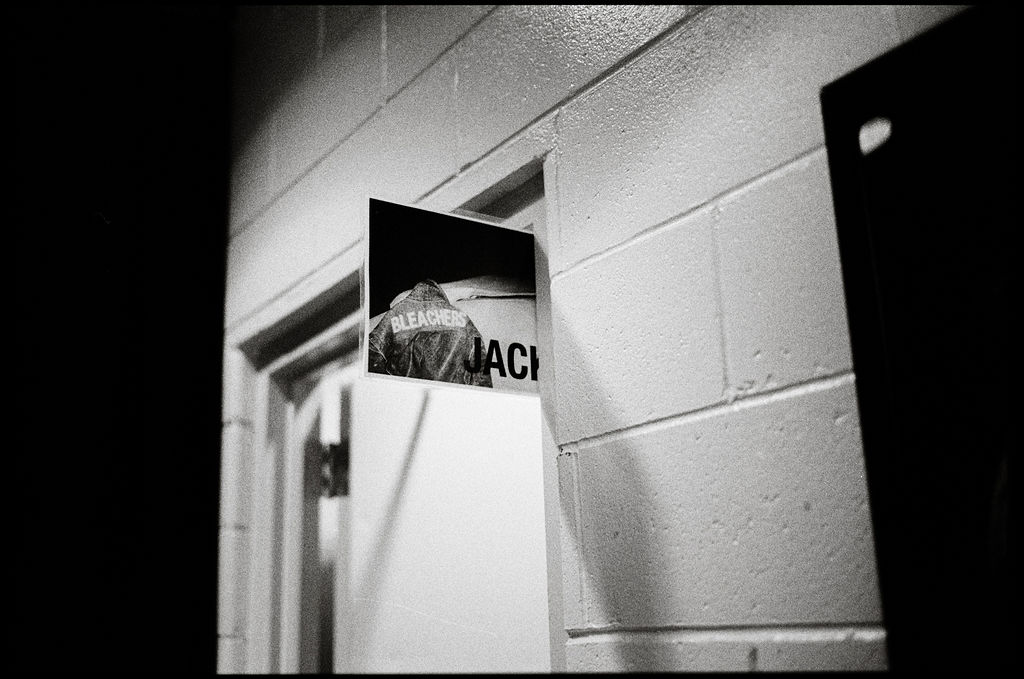

When 11-time Grammy winner Jack Antonoff arrives backstage at Madison Square Garden, he’s calm, cool, and collected, sprawled out on a red velvet couch as he fiddles with the cap of his water bottle. You would never guess from his demeanor that in just six hours he’s about to play the biggest show of his already illustrious career. “We’re in a really rare zone, and it’s not lost on me”, says the Bleachers frontman as he adjusts his signature chunky round glasses. Some of music’s biggest pop girls and frequent Antonoff collaborators like Taylor Swift, Florence Welch, and Sabrina Carpenter have sat in this very same room, but now it’s Antonoff’s turn as he and his bandmates prepare to play for 18,000 screaming fans for a special “One Night Only” show at the Garden. A few hours later, he trades his laidback, pre-show attitude for that of a swaggering, leather-jacket-wearing rockstar, but first we sat down with New Jersey’s finest export to talk about his band’s new self-titled album, what he’s learned playing alongside T-Swift, and why he isn’t listening to “bots and shitheads” on the internet.

———

ARY RUSSELL: Testing, testing. There we go.

JACK ANTONOFF: Testing.

RUSSELL: What’s going through your head?

ANTONOFF: I get pretty relaxed on show days.

RUSSELL: Oh, really?

ANTONOFF: Yeah.

RUSSELL: I’d be so nervous.

ANTONOFF: No, I like it. Because you know how on a normal day there’s so many things you want to do? There’s something really relaxing about the fact that there’s one goal for the whole day. It’s just the show. I think one of the reasons why I love touring so much is it doesn’t stress me out. It actually makes me feel the opposite.

RUSSELL: So it’s cathartic, almost ritualistic?

ANTONOFF: Yeah. I like the sameness of the day and how different the show is every night. It’s just sweet for me.

RUSSELL: On your last tour, you played Radio City [Music Hall]. That’s a really iconic venue. How does it feel to upgrade to an even more iconic venue?

ANTONOFF: It’s crazy. We’re in a really rare zone, and it’s not lost on me. It’s crazy.

RUSSELL: Growing up in Jersey, did you have any memories of coming to the city for concerts?

ANTONOFF: Oh, yeah. We didn’t go to the city that often, even though we lived so close. Maybe just a few times a year. But I think my first show ever here was Green Day and Weezer. And Hole played that, too.

RUSSELL: That’s sick.

ANTONOFF: The Smashing Pumpkins, too. Yeah, so this is the craziest. But I get very specific about our shows. With our shows, there’s nothing before and nothing after for me. I don’t want it to be like anything else. I don’t want it to draw from something I saw as a kid or something I’ve imagined here or there. Even if it’s in a space that means so much to me, it makes me want to do our thing even more, but that just came from years and years and years of touring. I just started pushing deeper and deeper into it being our thing. So that’s the only thing on my mind.

RUSSELL: Creating a unique experience that’s really specific to you.

ANTONOFF: The Bleachers are out here. Where are you from?

RUSSELL: I’m from Jersey.

ANTONOFF: Where?

RUSSELL: I was born in Bloomfield, Essex County. But my family, we moved to the Bronx pretty fast. I also relate to you in a different way because I know that you went to art school and I went to art school. So I wanted to ask you, do you have any art school horror stories that shaped you as a musician?

ANTONOFF: My art school was very sweet and I liked being around people who all had very different interests. I went to public high school for two years and that was like a teen movie, practically. It was still jocks and cheerleaders. There was a very small group of people who I thought were interesting. And then once I went to art school, I found everyone really interesting for different reasons. But at that point, I started getting high a lot and wasn’t going to school a ton.

RUSSELL: Real.

ANTONOFF: Yeah. [Laughs] So I don’t really remember too much.

RUSSELL: You mentioned the jocks and cheerleaders at your public school. Did that inform the “Bleachers” name, that high school nostalgia?

ANTONOFF: I always think the music is coming from a corner. It doesn’t feel like it’s coming from the center. It feels like it’s vibrating from somewhere else, so the word “bleachers” just spoke to me in that sense. But it was weird because I graduated high school in 2002 and it still felt like the ’50s. It was fucking bizarre. It was just like, “This is what everyone does, this is how everyone does it, and anyone who doesn’t is sitting at that table.”

RUSSELL: And I’m sure in Jersey, even though it’s right next door to New York, you might have felt stuck.

ANTONOFF: It’s another world. And if anything, how close it is makes it even more apparent what another world the city is, because you’re right there. But so many people just don’t come into the city or don’t enjoy the culture of the city. And over the years I came to just obsess over the culture of New Jersey, which is funny because when I was growing up, all I wanted to do was get out.

RUSSELL: I was going to ask you how you saw the city growing up.

ANTONOFF: I wanted in so bad. All the concerts, everything was happening there. And then as I got older, The Strokes were happening, and then the whole Brooklyn thing was happening. I always wanted to be a part of it and I just wasn’t. Then at some point later in your 20s, you start to get a deeper sense of who you are, hopefully, and I realized what a power that was, ao I started writing more from that perspective and it just led me to sound more and more like myself.

RUSSELL: What would you say is the most Jersey thing about you?

ANTONOFF: Wanting to leave Jersey.

RUSSELL: [laughs] Let’s go back a little bit to talk about your 2014 debut album, because you did a re-release for the 10-year anniversary. 2014 has a very specific vibe, Tumblr, indie sleaze. So now that you’ve reimagined that album, how do you feel about the recent resurgence of that aesthetic?

ANTONOFF: I never think too much about that stuff because I feel like there’s never a time that I can remember where something wasn’t coming back. [Trends] move so quickly that I find myself pretty unfocused on all of them. I feel like if something is happening, it’s already over. Not too long ago, the ’90s came back and then morphed into more early 2000s, re-contextualizing things that were lame at that point. And then it jumped all the way to this Tumblr aesthetic. I notice them like cars passing by. And also, I don’t like it when people were like, “I lived through that and let me tell you…”

RUSSELL: “Back in my day.”

ANTONOFF: Yeah, exactly. I notice it and then I’ve committed myself to not having any thoughts. At the end of the day, you go through modern history, the jeans get bigger, the jeans get smaller, the jeans get higher. You can see people’s hip bones, then you can’t. So obviously, this is a metaphor for everything. And anyway, anything that I want to be a part of is outside of that.

RUSSELL: Let’s move onto Bleachers self-titled album. Lana [Del Rey] appears on “Alma Mater”, and Florence [Welch] on “Self Respect.” What, in your opinion, makes them valuable contributors to your work, as opposed to your contributions to their music?

ANTONOFF: It speaks to me, ‘cause a lot of these records were all happening at the same time, so the cast of characters that end up on things is just a reflection of my life at that point in time. It’s a nice way of tying my production work to who’s around me at that moment, because in one studio day I’ll be doing a Bleachers thing and someone will come by and I’ll do something else, so I like to signal to the audience that these are all happening in real time.

RUSSELL: On “Self Respect,” you make references to specific pop culture moments like Kobe’s [Bryant] death, the Kendall [Jenner] Pepsi incident. I’m curious if you’re looking to create a snapshot of a specific moment in time.

ANTONOFF: In that song, I reference things that are real, but they happened a while ago, so I felt comfortable referencing them because it didn’t feel like I was dating it to the second I was reflecting on it. I don’t set too many rules for myself about what I do or don’t want to say. It’s more of a feeling. Everything changes so quickly that all you really have is trying to express what it’s like to be inside of you and what you sound like and what you think. So I really run from anything that doesn’t feel or sound like the words in my head. And then if the words in my head feel overly attached to a specific time or moment, I just forgive myself and use them.

RUSSELL: On the subject of forgiving yourself, I see “Self Respect” as your messy girl anthem, because you talk about doing things that you’re probably not supposed to. So I wanted to ask you, do you have a time where you did something that you weren’t supposed to but you were just like, fuck it.

ANTONOFF: Oh, many times. Part of the joy of being a human being and changing and growing is finding the edges. That song is really about rejecting other people’s version of self-respect. So if you think about the tenor of the entire internet, the internet is basically one giant cop just telling you what you can and can’t do at any given time. And I’m not interested in the post-woke “be disgusting” movement, because that’s not me either. But I do retain this personal right to not be perfect and to be messy with my emotions and thoughts. And so I wrote that song because I was like, “I don’t want to have anyone else’s definition of self-respect. I’m so tired of seeing self-respect in terms of this culturally specific version of self-respect that changes every five minutes.” So, “Kobe fell from the sky” is someone I didn’t know dying, and it was tragic. “Kendall Pepsi-smiled,” like some goofy advertisement, “The day that I had held her last,” talking about the death of someone in my family.” I was trying to paint a picture of the whole spectrum of life: personal things, silly things. What’s the next line? “These days of our lives are rough and they’re fast and unfair.” It’s all moving quickly and it’s all tough and not everyone’s a total piece of shit. And the cultural, collective version of what self-respect is is usually defined by bots and shitheads. I don’t know, I just felt like writing a song that was defiant against it. At the same time, I don’t want to have some giant baby reaction and say a bunch of awful shit just to break culture. That’s so stupid and so embarrassing. Like, “What? Are you having a tantrum?”

RUSSELL: “Grow up.”

ANTONOFF: Nazis have never been cool. You know what I mean? Being a fucking asshole or being a racist has never been cool, so that embarrasses me also. Are you that black and white in your head that you’re either a perfect internet pawn or you go full incel? Jesus Christ, just be a human being. And I know too many people who I saw that happen to and I was just like, “Everyone complains that there’s no nuance in the internet, so then write a song with nuance in it.” It’s just complicated.

RUSSELL: So we’re backstage and you’re about to go into your soundcheck. Your longtime collaborator, Taylor [Swift] has obviously played huge stadiums, and you’ve often joined her on stage. Are there any lessons that you’ve learned from her?

ANTONOFF: I learn lessons from everyone constantly. The last time I saw her was in London and I played, too. I feel like anytime I see a show, whether it’s someone I know or not, I’m so wrapped up in that moment that I’m learning so much, But also, I don’t know, Bleachers is such a specific protected space that comes from the six of us. It’s not buzzing around anything but what we’re going to do. The shows are an explosion of what the six of us are feeling and what our audience is feeling, so I don’t think beyond that ever.

RUSSELL: I know you have to get ready soon, but I wanted to touch on your recent efforts to put music studios at LGBT youth centers. What kind of impact have your LGBT fans had on you?

ANTONOFF: It’s a sad fact that a lot of times some of the most incredible work comes from people who are mistreated in society. It shouldn’t be that way, but often those stories cut through in an amazing way. So I’m very shaped by a lot of work through the years that come from the LGBT community. And I started a non-profit over a decade ago called The Ally Coalition because I grew up going to shows and everything was like, “Show is $5, or $3 worth a can of food. This is a Food Not Bombs benefit. ” If you’re going to gather people, it’s pretty easy to make a small difference and it seems like a missed opportunity not to. So yeah, I think that I’ve learned how to build studios and create these spaces and I just thought to myself, “How could it be something that society values?” When you’re on a plane, sometimes you think to yourself, “Do we need another baseball diamond?” So I just started thinking, “Oh, think about how much people in government spend on parks and basketball courts and all this stuff all over the city. There should be a place where people can go and spend time in a recording studio and see if it’s something that is interesting to them.” It’s going to be cool.

RUSSELL: Any plans for after the show?

ANTONOFF: I want a burger after the show.

RUSSELL: Oh, okay. A burger.

ANTONOFF: I don’t eat a lot before the show. I like to feel light. So after the show is an at-risk time for me where I could easily eat everything.