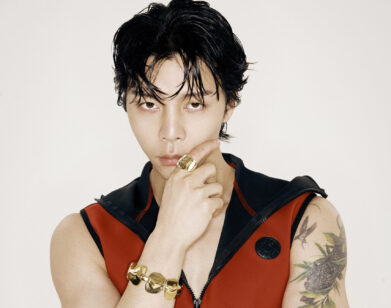

Re-Introducing: A.A. Bondy

PHOTO COURTESY OF A.A. BONDY

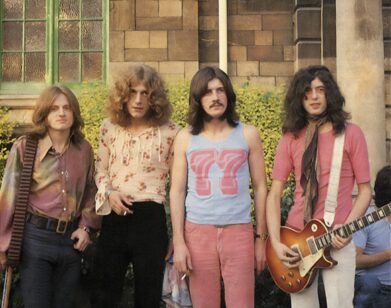

Once upon a time, A.A. Bondy played in a loud band called Verbena. When they broke up in 2003, he ran off to the Catskill Mountains to duck out of the music business for a while. But, in 2007, he re-emerged with a record called American Hearts. While his previous band had garnered comparisons to Nirvana with their aggressive, gritty guitar-rock, Bondy’s solo work is seriously lovelorn and melancholy, an effort that sounds like it could have been recorded 40 years ago on someone’s far-away back porch. In 2009, he released another great record, When The Devil’s Loose, which found its way into many of that year’s “Best Of” lists, including mine. I spoke to him from the road in southern California.

T. COLE RACHEL: You’re out in California now. Do you like touring?

A.A. BONDY: It changes all the time, because the circumstances are always different. It’s just so weird–the things you can get used to–the perception of where you are changes over time. When I put out that first record, I would go out and tour with anybody–play play play play play–and now it’s like, “Work smarter, not harder.” You know, we saw a double rainbow like ten minutes ago with the Pacific Ocean to our right–I don’t get to do that everyday. Then you’re just on some highway in the middle of Colorado for miles and miles and miles of nothing, and you go lay in a bath tub. Peaks and valleys.

RACHEL: You played in a much different kind of band before, and then you stopped for a while. Was there a point at which you thought you’d quit music forever?

BONDY: I never stopped playing instruments, and going to my friends house and playing Rolling Stones covers in the woods by bonfires. It was those things that got me used to playing with people again. And just what its supposed to be about, for me. Which is just whatever that moment is, whatever joy can be wrung from it. But when I first decamped in New york, I just forgot that there were other ways to do thing in the course of those years. It just took a while. My friend and I have this joke that we never learn anything except the hard way, I have to grab the electric fence four or five times before I’m sure it’s going to shock me.

RACHEL: At least you learn it eventually.

BONDY: Exactly.

RACHEL: There must be freedom and autonomy to doing things on our own that you don’t really get when you are in a band.

BONDY: I think it’s easier psychologically for everyone. Bands–ones I’ve been in or ones I’ve been close or seen how they work–they just maintain this air of adolescence forever. Most relationships, band or otherwise, are a lot of work. But in this situation, we have the illusion that we’re not a band, even though I’ve had these guys with me coming up on a year now, and it’s a joy to play with them. Everyone can have an idea, but it’s not all this other stuff about splitting money, as long as I take care of you and we’re enjoying it, we’ll do it. It’s not band that turns into family and family gets weird.

RACHEL: These two records have a heavy classic American blues influence. Was that what you grew up listening to?

BONDY: Not really. I always come to things late. Whether it’s movies, or music, or sushi, whatever, it takes me a lot of time to come around to things. In Los Angeles, a friend Sean Brown had put together this video of Reverend Gary Davis and Mississippi John Hurt playing on Pete Seeger’s show ,and I had heard John Fahey and I had the Robert Johnson record, of course. I enjoyed them but I didn’t ever realize what was taking place musically, specifically the right hand of those guys when they played, until when I saw it, and I was transfixed by it. I got really into finger-picking–a lot of those songs are me doing my take on that stuff. The ones that are just like that, they are pretty traditional forms, but I had to do that to get somewhere else–an arsenal of technique.