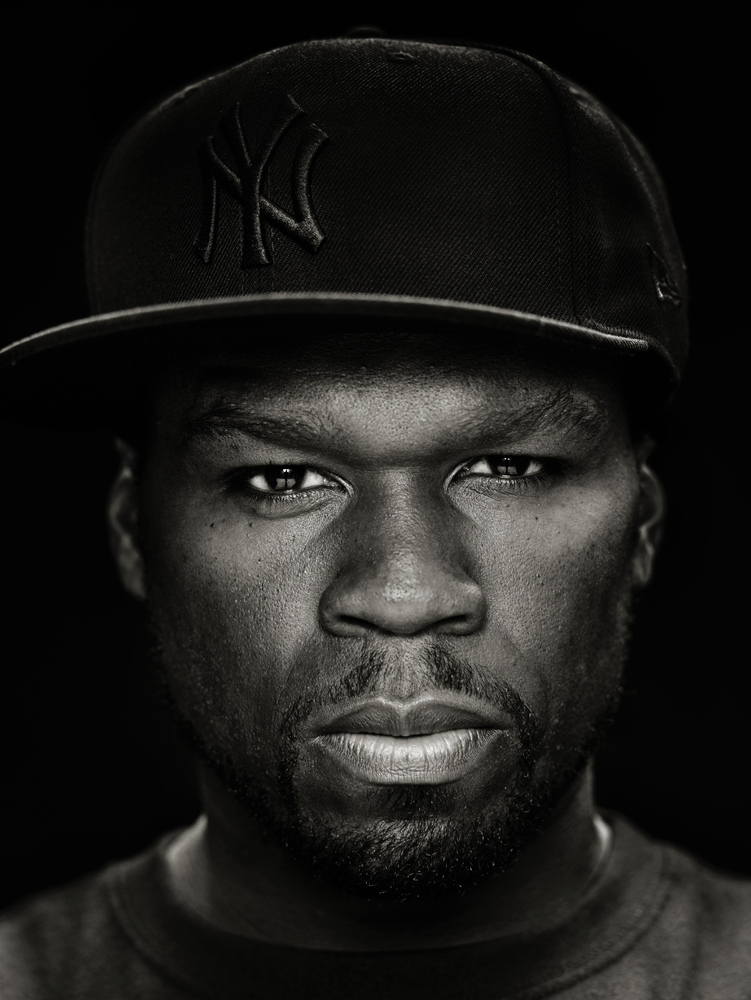

50 Cent

The story of how Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson survived the streets of South Jamaica, Queens, and took nine bullets on his way to becoming one of the most successful hip-hop artists of all time is by now the stuff of music lore (and movie lore too, dutifully reenacted by 50 himself in Jim Sheridan’s 2005 film, Get Rich or Die Tryin’). But as 50’s list of hit records (his albums have sold 36 million copies) and prime-time feuds (with Kanye West and The Game, to name two) have mounted, another -narrative has emerged: that of 50 Cent the multimedia, multihyphenate, multibusiness mogul. Between his music and his various interests in clothes, sneakers, films, books, video games, television shows, fragrances, cars, and sports drinks, the fortune he has amassed over the past seven years is estimated to be northward of $400 million. In fact, in September, Jackson even released a book titled The 50th Law (HarperStudio), written with motivational guru Robert Greene, which offers instruction on subjects such as how to turn an idea into a viable business model and tips on organizational management for budding street-bred CEOs. Lately, though, 50 has been doing more than just -watching CNBC: His recently released new album, Before I Self Destruct (Interscope), features guest spots by Eminem, R. Kelly, and Ne-Yo, and of course, his trademark mix of hyperaggressive wit, testosterone, and ferocious swagger.

DIMITRI EHRLICH: I’m struck by how much your career has diversified beyond music during the past few years. You now have a record label, a book imprint, the 50 Cent video games, the G-Unit fashion label, the G-Unit sneakers, your own fragrance; you designed a car for Pontiac—it’s even been reported you made $100 million from your stake in Glacéau. And on top of all that, you got to act alongside Robert DeNiro and Al Pacino [in Jon Avnet’s 2008 film Righteous Kill]. I assume that now you’re probably earning more money as a business mogul than as a rapper. Is that a correct assessment?

50 CENT: Absolutely. I’ve already exceeded what I’ve earned from music with my other ventures. I always had what I thought were good ideas, but I didn’t have the finances to support them. The interest generated through the success of my music on a broad scale—like being able to sell 19 million copies of my first record [Get Rich or Die Tryin’, 2003] worldwide, and then following up with the 13 million that sold of The Massacre [2005]—has allowed that to happen. The last album, Curtis [2007], didn’t sell as many records as the other ones, but obviously the climate in the music business is changing. I mean, when Curtis came out, collectively me and Kanye were able to create the biggest-selling week for hip-hop music in that time frame. But all of these projects have created a new energy for me when I’m working, and

I taste it—I’m more feverish.

EHRLICH: Do you know what you’re worth today? I’ve read that it’s somewhere in the area of $400 million. Is that accurate?

50 CENT: [pauses] I’m not sure, but that sounds great.

EHRLICH: [laughs] When you have that much money that you’re set for life, how does it change your feeling about yourself? Or is it just never enough?

50 CENT: I don’t really think it’ll ever be enough. I used to equate success with my finances because I didn’t have anything, and when you don’t have any money, it seems money is the answer to all your problems. Then you get money, and you realize that you’ve got a whole new set of problems.

EHRLICH: Your first two albums sold 32 million copies combined, and then Curtis sold one million. Do you feel like with the new one, Before I Self Destruct, you still have a lot to prove?

50 CENT: What? One million records?

EHRLICH: Domestically—wasn’t that the total sales figure for Curtis?

50 CENT: It was more than a million records. I’ve never had an album that sold just a million records. I’d be devastated if I sold one million records.

EHRLICH: Okay, so how many copies did Curtis sell?

50 CENT: I don’t even know. Hold on. [asks someone off phone for sales figures]

EHRLICH: Anyway, we can look it up, but my point was not to belittle the album. No one is selling 20 million records anymore.

50 CENT: Yeah. And I understand that the music itself determines whether you’re generating interest, so whether you actually sold the copies or the kids are sitting in front of the computer and downloading the music that way, it still determines how relevant you are.

EHRLICH: You’ve had a lot of high-profile beefs in the past, but less so lately. Do you feel like you have too much at stake now, or are just you feeling less confrontational?

50 CENT: I mean, it just has to make sense to me. You know, like, when I’m getting into it with an artist who wants to be in the position I’m in. It’s just a fact—it’s based on him wanting to be in the position I’m in.

EHRLICH: Hip-hop is interesting to me because it doesn’t allow you to be very vulnerable. Do you feel like it limits the reality of you as a human being when you can’t express the full realm of your feelings sometimes?

50 CENT: Well, that’s when you can go off and be a part of those film projects and be vulnerable and everything else that you want to be as an artist. They’ll say you’re weak if you’re out crying on the stage while performing as a rapper, and they’ll say you’re amazing if you do it on cue in a movie scene. But you’re only human. You have emotions. It’s just that some of us know how to suppress them better.EHRLICH: Do you get annoyed that people are afraid to say no to you?

50 CENT: Well, I have friends that treat me the same way they did before I was the boss. They don’t actually want anything from me.

EHRLICH: Like who? Who’s your best friend?

50 CENT: My best friend? Damn. Probably Eminem. We don’t get a chance to hang out much, but we use the telephone. When I was in Detroit, I stayed at his house. He provided an opportunity for me, for all of these things to happen.

EHRLICH: Do you still only communicate with your ex-wife, the mother of your son, via lawyers?

50 CENT: I don’t have any communications with her.

EHRLICH: Do you ever think, with all this wealth and success, there are some things money can’t buy, like a happy marriage?

50 CENT: Yeah, but then you have people who don’t have any wealth and find themselves in spaces where relationships don’t work. People are like plants: They grow; they change every day. When a person completely has nothing but negative interest in you and would like nothing more than to see you in the worst situation possible, then why would you consistently go toward that energy?

EHRLICH: I would assume that one of the most difficult things you’ve had to negotiate in life was the loss of your mother, who was murdered when you were eight years old.

50 CENT: Exactly.

EHRLICH: Do you remember that moment—getting the news? How has that loss continued to affect you to this day?

50 CENT: Well, I was a baby—I was eight when my mom passed. The reason my mom made the choice of going into the lifestyle she went into . . . I was the motivation for her going into that. She had me when she was 15, and teenage pregnancy wasn’t as common as it is now. And at that point, there’s no blue card. Your options were either to go on welfare or to go into the lifestyle that she went into, hustling to get what she could provide. So I remember my mom and associate her with everything good because every time she showed up, she had something for me. I never knew my father, so she was everything, you know? After I lost my mom, I can remember feeling like I wanted to go into a park but it was raining outside, and I felt like it was raining because my mom was dead. Literally, I used to feel like everything that was going wrong was going wrong because my mom wasn’t there. I remember when she passed and my grandparents told me that she was going away, that she was going to be in a better place—I didn’t understand that. Went to her funeral and everything and still didn’t understand what was going on. Just knew that everything that was good went away. And then all of the people that I ran into who appeared to have a nice lifestyle, the things that I wanted, like nice cars and nice jewelry—people who were well-kept and looked like they was living good—they were all from my mom’s life. They said, “Hey, what’s up, little Sabrina?” They used to call me my mother’s name because they knew me as Sabrina’s little boy. They’d look down and be like, “Why your shoes look like that?” And then they’d buy me shoes. And afterward, they’d take me aside and say, “Hey, if anyone bothers you, then you tell ’em you got those shoes from me.” And that’s giving you a license to actually sell the shit in the neighborhood. But even when I was selling, I had to do it between 3 P.M. and 6 P.M., when my grandmother thought I was in the after-school program.

EHRLICH: Did you ever sample the goods when you were dealing drugs?

50 CENT: Nah. As far as getting high was concerned, it was easy: Do I spend $10 on some weed and smoke it, or do I hold on to $10 that I need to live?

EHRLICH: What would you say is the art of a true hustler?

50 CENT: True hustlers are prepared to get hustled and know when to change positions and move to something different and aren’t afraid. Even the toughest guys are afraid to be anything outside of the toughest guys.

EHRLICH: Your charity, the G-Unity Foundation, gives grants to low-income kids to get through school, which makes perfect sense, but explain why when you opened the Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson Community Garden [in Jamaica, Queens], you partnered with Bette Midler, whose core audience is, well, very different from yours.

50 CENT: Yeah, her core audience is different from mine, but we had the same intentions at that point: We were working together to do something positive for the youth in that area. Bette is probably one of the top 100 philanthropists in New York City, and to get with her and do something positive in my actual neighborhood made perfect sense. Following that, we’ve been a part of other projects together. I don’t actually promote what I do for charity—you shouldn’t even be doing it if you’re doing it to promote it. But what’s troubling is that I sometimes feel like I’m being held to standards that they don’t usually hold other people to. Like, we did this event called Family Day in Queens, and they made me have licensed vendors for food, but they didn’t give me the sound permit. And then Mayor Bloomberg and the governor—it’s on the Web now—they were talking about how they reached out to me and I told them that I wasn’t going to perform, that I was just going to attend it. But one of their stipulations was for me not to actually perform at the event. The New York Post wrote negative articles about it; they said I’m a “bullet magnet”! They printed a two-page story showing the distance from where I got shot to the location where I was trying to throw the event. I don’t think they realized that the event was for kids. You see what I’m saying?

EHRLICH: Right, you’re just trying to help kids, and they’re being insulting.

50 CENT: Right. So it’s interesting. I got my ass kicked for trying to do something cool, you know what I mean?

EHRLICH: I read that you don’t mind flying coach. Is that true? How do folks react when they find themselves sitting next to you in economy?

50 CENT: Well, I really don’t mind flying coach if I have to. If the front of the plane is sold out, I’ll sit in the back. Some people are like, “Oh, first class is sold out. I can’t go.” I guess they care about people seeing that they’re not sitting in first class. But I’m clear with my financial space—I don’t need to get any validation by someone else who sits next to me in first class. If you think a seat in first class makes you a star, then you’re not one.

Photo: 50 Cent in New York, July 2009. Fragrance: Power by 50 Cent. Styling: Mia Quinn. Grooming: Lionel “Lite” Jones. Production: Larry McCrudden for THECUSTOMFAMILY.COM. Special Thanks: Root Brooklyn.

Dimitri Ehrlich is a contributing music editor for Interview.