IN CONVERSATION

Why Kathleen Alcott and A. Savage Said Goodbye to All That

Coursing through the fiction in Kathleen Alcott’s marvelous debut short story collection Emergency are familiar anxieties about class and privilege, men and violence, about striving and its literal and psychic limitations. The protagonists in these seven stories are often women, and though many of them have found ways to transcend impecunious origins, they struggle nonetheless with their friendships, husbands, boyfriends and the dark underbelly of upward mobility.

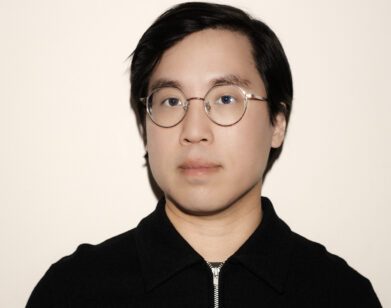

Class—and Americans’ queasiness with the topic—came up again when Alcott got on Zoom earlier this month with her friend A. Savage, the frontman for the rock band Parquet Courts. “The myth of this country is inherently neoliberal, that there are no social classes, that ascension is easy,” Alcott said. “It’s very comforting to us up until a certain point, and then it’s corrosive.” Savage, who today announced the October 6th release of his second solo album Several Songs About Fire, had just recently moved from Brooklyn to Paris, a decision compelled in part by the lure of solitude and the strain of being a creative in America. “I want to be somewhere where I’m just a little bit better taken care of as an artist,” he told Alcott. Over one hour, and an ocean apart, the two discussed Emergency, Savage’s forthcoming album, the use of nostalgia in art, the vitality of close friendship, and saying goodbye to New York City.

———

KATHLEEN ALCOTT: How are you doing?

A. SAVAGE: Hey, I’m doing good, Kathleen. What’s up? Where are you?

ALCOTT: I’m in California doing some swimming. I don’t know, it’s publication week, which always feels like a [Luis] Buñuel movie or something kind of hallucinatory, like something strange might happen at any moment. How are you?

SAVAGE: I’ve only seen, what is it? The Exterminating Angel?

ALCOTT: I’m thinking of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, where there’s this amazing scene where there are a bunch of people around a dinner table and they’re sitting on toilets, shitting in public, and they’re like, “There are people eating in the other room,” and they’re ashamed by it.

SAVAGE: Right, right, right. It’s funny because, in the movie I just mentioned, The Exterminating Angel—it’s about people who are also at a dinner party, but they can’t physically leave it.

ALCOTT: Oh, that’s my nightmare.

SAVAGE: Oh, that’s interesting.

ALCOTT: You were emailing me about dinner parties the other day.

SAVAGE: I think Helen and her ex [characters in the title story of Alcott’s collection] probably threw a good one.

ALCOTT: What was your experience of reading that story, given that it’s narrated by a bunch of people who aren’t the character?

SAVAGE: That’s a question that I was going to ask you, actually, because I think one of the most fascinating characters is Helen. I think one of the things that makes her the most interesting is the way she’s narrated by this Greek chorus of her friends, and the perception of Helen is this kind of streamlined thing that’s been eroded into shape by the collective voice of the group. And sometimes I narrate my own life that way, as if all my friends are watching what I’m doing, and what they would think. But we really never know that, I guess. So that was my experience reading it. Why did you think the reader needed to know about Helen that way?

ALCOTT: First of all, I just think that it’s interesting that that’s a universal experience of the ego, which is that we imagine there’s a little newspaper that is managed and printed by all the people who love us, or maybe don’t love us anymore, and that these articles are constantly being written.

SAVAGE: It’s not just me? Okay, good.

ALCOTT: I felt that it was a much more interesting story if the voice telling it was a kind of insidious and internalized misogyny. All of those narrators are women, and I think they’re probably more evil and judgmental [together] than they would be on their own. When it comes down to their generosity, it’s always diminished by their need to be a part of a consensus. I should say very explicitly that the character in that story is not me. But there was this summer where I went through what felt like a very public breakup. I was living alone, I was swimming a lot, I was traveling a lot. But I felt like I was experiencing judgment from people who were on a more traditional path. And I kind of thought, “What if I just narrated my fears about what people are thinking about me, the vilest things they could possibly be imagining about my life?” And it was extremely painful and meaningful, and I’m glad that I did it. In short fiction, I think there’s always a kernel of my life, which is triangulated against, “What if this happened to someone who is very different from me, and how would they have responded?”

SAVAGE: Well, I thought that your use of collective narration was a really interesting device that I would use. It seems to me that I can relate to that character because she’s moving away from a group. I’m living on my own for the first time ever in my life.

ALCOTT: I’m so happy for you. How has that changed your routine?

SAVAGE: Well, because I’ve always lived with other people, I’ve been programmed to do my dishes because I hate those roommate talks, giving them and receiving them, when somebody’s disappointed with the other person’s roommate etiquette. And so I still hear that voice, even though there’s nobody there to give it to me. I rarely leave the dishes in the sink, but I did it the other night, and—

ALCOTT: Did you leave yourself an aggressive Post-It note?

SAVAGE: No, I wouldn’t do that. But when I saw them, I was kind of two minds. One mind was like, “Ah, you pig.” And then the other part was like, “Hell yeah, I’ll leave my fucking dishes in the sink. Nobody’s here to tell me otherwise.” So I guess there was an imposed narration of this phantom roommate.

ALCOTT: Look, I love to talk about house chores, but I do have a question. I’m thinking about your record and there’s that lyric about the gods who held your heels and then, two songs later or something, the gods who don’t exist or care. You’re such a poet. I don’t know what my question is about that—are you aware of these threads that are broken and re-strung, the thematic unity of that?

SAVAGE: I guess I’m aware of it insofar as anyone is kind of aware of their own lexicon. I think as either songwriters or fiction writers, you have these archetypes. That is kind of what attracts me to the classics. But oftentimes, with specific things like you just pointed out, it’s not as intentional as you might think. As an artist of any sort, there’s just some things that you don’t even see in you that come out.

ALCOTT: That’s always astonishing to me. I’m glad because I prize control above all else, but it’s always comforting to be reminded that your subconscious is as culpable for what you create. I was promoting an Italian translation and this interviewer pointed out that in my last novel there was no physical description of a female protagonist. And it had never occurred to me that I’d done that, but it was obviously a lacuna that was intentional because like, all of my fucking work is about misogyny, and I wanted there to be an appraisal of her that was purely psychic, or purely spiritual.

SAVAGE: Right. You have an English character in there, too. And we’re not so different, us and them, they just talk a little bit funny. But one thing that they always do is point out and identify class in themselves and others, and people’s public behavior and the way people talk. And we don’t do that as Americans, really. In fact, we avoid it, we sweep it under the rug. But it doesn’t have to be, necessarily.

ALCOTT: Yeah, the myth of this country is inherently neoliberal, that there are no social classes, that ascension is easy. It’s very comforting to us up until a certain point, and then it’s corrosive. Do you want to talk about the fact that you just left the country—

SAVAGE: Sure, we can talk about it.

ALCOTT: How’s that feeling for what you’re working on now?

SAVAGE: Well, given the brutal decisions that the Supreme Court made shortly after I left, it kind of made me think, “Okay, maybe I’ve done the right thing here.” But I’m also living in a really problematic country, it seems. So I’m not in a Shangri-La or anything.

ALCOTT: Where in Paris are you? So we know.

SAVAGE: I am in Barbès.

ALCOTT: Okay, beautiful.

SAVAGE: It actually I guess reminds me a lot of Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, where I lived for 12 years in one apartment, so I guess there’s a comforting element to that. But yeah, I got to a point where being an artist, at least the type I’m at and the world that I’m in, became incongruent with surviving in America, having healthcare. Which is a deep shame. The things that make me proud of being from America are that we invented so much music that the world loves. But I can’t really afford to take care of myself in America because of this really bizarre death cult idea they have in that country that if you’re not doing everything you can to survive, then you deserve to die. I forget which fucking Republican debate it was, where someone was like, “What should happen if a cancer patient can’t afford treatment, and under our current system, they don’t have access to treatment, what should they do?” and then someone from the audience shouts, “Let them die.” And that’s such a dark piece of the American psyche, this idea that, “If you’re not busting your ass the way I am, then fuck you. Get out of here.” So I don’t know if I’m going to stay here specifically in Paris, but I want to be somewhere where I’m just a little bit better taken care of as an artist.

ALCOTT: I think about this a lot as a novelist, and I wonder if you do as a musician. To enjoy a book, or to really enjoy a record, I think one needs a certain amount of concentration and stability. I need to understand it and value it and let it rub against me as the listener or the reader. So as an artist, you’re kind of creating this middle class object insofar as the people that you’re reaching have probably attained a certain amount of stability. It’s probably less true for those attending a rock show. But how do you feel about that, about producing things that are received by people in that demographic?

SAVAGE: Yeah, I guess it’s people in that demographic that buy tickets to concerts, and buy T-shirts, records, et cetera, and allow me to do what I do. I guess the difference between music and novels is that there’s the radio. You hear music in bodegas, you don’t often walk down the street and hear someone reciting a novel. It’s a very active type of consumption, you have to go buy the book. Anybody can listen to my stuff for free, so it really has to be someone with disposable income who buys something they could have for free.

ALCOTT: We were talking about antiquity and the Greek chorus and about money, and I was thinking about the timelessness of your record. There’s so much of the natural world, and then there’s so much modernity, there’s a lot of money and debt, just a lot of clutter that I love. There’s the detritus of life. And I don’t know what my question is there, except how you feel about swinging between those two poles. I see you as being a very sensuous person and also a very cerebral person, and I wonder how you think about those two parts of yourself interacting as an artist, particularly on that record.

SAVAGE: First of all, I think that trying to articulate a hyper nowness can be a bit obnoxious sometimes.

ALCOTT: A hyper nowness?

SAVAGE: Yeah, nowness.

ALCOTT: Oh, I see.

SAVAGE: But also, so can focusing on the past, this sort of nostalgia thing. To me, as an artist, it doesn’t make sense not to address things like texting, or any of the very relatable things, because that’s just part of rock music or pop music, really. But also, when you put too much emphasis on nowness, it makes it kind of disposable. And I think that’s one of the things I like about hip-hop, that it’s very self-aware in how disposable it is. It’s all about nowness, it’s all about the most up-to-date slang. Rock is always somewhat tethered to this kind of origin point, to Little Richard, and you always have to be able to pull your rope back to him. I guess there are people who do pure nostalgia things and tribute kind of stuff, and that’s fine. [But] if you want to be relatable to an audience, and make them see themselves in you, then there’s got to be a mix of both. Because if you just lean on one, it becomes corny.

ALCOTT: Is that temptation for atavism or nostalgia is so particularly strong in rock and roll in a way that it isn’t in other genres? It isn’t bad in painting, I don’t think. I certainly don’t think it’s like that in literature.

SAVAGE: I think because it started becoming that very quickly. It became that very early on in its defining moment, when the first few [Rolling] Stones records are a lot of covers. A lot of the British invasion started doing covers of American music. So I think maybe there’s an alternate history where it evolved differently, but it just wouldn’t be what it is. It’s the thing that I think puts people off about rock and roll. Sometimes you hear things like, “It’s all been done,” which I think is a really pessimistic way of thinking. Because when you’re writing a song, what you’re essentially making is kind of like a time capsule, so you want it to be true to your moment. That’s why we’re still captivated with songs about the Vietnam War, because it takes us there.

ALCOTT: That’s so interesting to me. You’re a person who technology hasn’t perforated in this same way it has almost everybody that I know. When I talk to you, I don’t know if this is a weird thing to say, but you’re like, “Oh, I went to this place, and I sat there and could hear this tree and this animal and this that.” There’s an aspect of that which is shocking to me. I don’t know, there’s just kind of a rejection of the Anthropocene.

SAVAGE: I think as an artist, you have to put up boundaries because it really is kind of like the siren song. If you really dive in, you’ll get stuck there. And I know people that are stuck there, and I see evidence of artists who are stuck there. Maybe this is going to make me sound old and bitter, but a lot of [art] feels like homework that’s done at the last minute because people live so online. I think being an artist is a lifestyle, and that can include technology, but it also really has to include being present. It has to include, to use a cringey neologism, being “in your day” and absorbing things outside of the internet. Or else, what you have to say isn’t going to be all that interesting because the internet is just this echo chamber where ideas are repeated. But when you look out into the world, it’s infinite. It’s getting harder to be an artist because of that. You have to choose a different path, really.

ALCOTT: I also feel like I have to choose people who are that way. I have to be around people who are choosing to have a sensorial experience all the time because otherwise I feel sucked into this very surface-level life on a screen, which I think was a part of leaving New York.

SAVAGE: I mean, that’s one thing about New York. It’s a bit cheesy, but I do consider it the greatest city in the world. But also you’re just forced to live in the marketplace, you’re forced to be in capitalism. I need to have another experience. You’ve moved around a lot more than I have, so maybe you can relate to this, but I just realized that I needed to shake it up and find another new way to identify, or a new thing to attach myself to that’s not necessarily a place.

ALCOTT: Many people in my life are a little scornful of the extremes of solitude I’ve taken, but I think there’s something very important that happens when you don’t hear your own name for a while.

SAVAGE: I find huge value in that.

ALCOTT: Living in New York, it kept happening to me that I would go for a jog and run into someone and be like, “Hey, how’s your job at Vulture?” or whatever. It’s like, “It’s not going to work anymore.”

SAVAGE: I think there’s a freedom in being a stranger somewhere, and I’m really relishing that freedom right now. In a way, I had too many friends. There’s really only a finite amount of relationships you can really have and put-

ALCOTT: I don’t want to ask how many.

SAVAGE: Well, I don’t know the answer to that. You can have a bunch of names on your phone, but you can’t really have too many real active-

ALCOTT: Well, if it’s the same number as the amount of phone numbers you can remember, it’s like seven. Or the first MySpace, “Choose your top eight.”

SAVAGE: Yeah, eight. That’s what you get, it’s eight.

ALCOTT: Eight seems fine, eight wonderful friends. I was just complaining to someone, a friend of mine sent me a screenshot, and it was someone he had texted who was talking about my book, and they said, “I really liked it.” And I said, “Oh, who is that?” And my friend said, “Just a friend.” And I was like, “Just a friend?” This is the cruelest invention capitalism has given us. What’s more precious than a friend? And the only reason that they’re debased that way is that they’re not going to augment your wealth or your social capital that much. It’s wild.

SAVAGE: But if you’ve made out with a stranger at a bar once, you’re more than friends.

ALCOTT: Can you tell me which five songs you would play on stage over and over again until you died?

SAVAGE: Of my own?

ALCOTT: I don’t know how this works in this situation. Maybe they’re not allowing you that. I think it’s other people’s songs. It’s all covers, and you’re a hack now.

SAVAGE: I bet I could answer this. Let me see. Maybe “Bobby Jean” by Bruce Springsteen, I can take it home with that. “You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me.” If I had a slightly higher range, maybe “Total Eclipse of the Heart.” Maybe “Like a Prayer,” that’s a song I easily get lost in and don’t often get tired of.

ALCOTT: I think that’s five. I don’t know. I’m a writer, I’m not a counter. But the gig is yours, you’re hired.

SAVAGE: Great. Glad to be here.

ALCOTT: There are no benefits though.

SAVAGE: The adoration of the crowd that night, that’s the ultimate benefit. Maybe this is the worst question ever, but do you think if these characters, these women, were at a dinner party—

ALCOTT: The characters in the first story or all of them in the collection?

SAVAGE: The collection. Certainly, there’s a lot they would have in common, there’s certainly things that they could talk about. But do you think it’d be a good conversation? Do you think they’d get on?

ALCOTT: I’m not sure. I think there’s something that’s fairly sinister that unites them, which is a bit of an Athena myth. They’re born of a male god’s forehead and they don’t need other people, particularly other women. It’s funny because it’s an ancient myth, obviously, but it also feels particularly American. I think there’s that line about Helen, “To any rule she would prove the brilliant exception,” and I think that it could probably be said for any of them. So I don’t know if they would be kind towards each other. It might be uncomfortable to be recognized.

SAVAGE: Right. I was thinking about it. They might not, but that would be a shame. So there’s three instances I can think of in the collection of someone finding a photo that they weren’t intended to see, but they’re all physical photos. They’re not stumbled on in a phone or a computer. That seems to be a conscious decision on your part. Do you think there’s something more to seeing the physical photo than seeing a digital photo?

ALCOTT: Well, let me think about that. There’s certainly something more talismanic about a physical object, which has been created by various processes and touched by various hands.

SAVAGE: The labor in it, yeah.

ALCOTT: So the idea that anything intimate would ever be captured and then developed in a dark room and sort of vouchsafed on a photo counter seems so completely at odds with how we’re living now. It’s funny, the critics who love and hate my work love and hate it for the same reason, which is just like, “Too many images.” And I think at a certain point I just realized that I wanted to think about a moment in time in a way that is tantamount to thinking about a photograph. I have a certain amount of native anxiety, and anxiety is very comforted by the idea that there’s a moment I can turn over and see from every angle. And you can’t in a photograph, but there’s an illusion that you can. The question is, what would you do if this is all the information you had? And that’s a question that could be posed about coming across a photograph or a certain remark that someone makes to you.

SAVAGE: Isn’t it wild that at one point, in regards to kinky photos, some people needed them so badly that they would submit them to a lab where they knew someone was going to have to process them?

ALCOTT: Maybe they liked that though. Maybe that was part of it.

SAVAGE: Yeah, maybe that’s part of it because they could have had a Polaroid.

ALCOTT: Andrew, these were such wonderful questions. Did we talk about your record enough?

SAVAGE: You’re way better at talking about your own work than I am, so I’m always happy to be the question-asker. When I talk about my own work, I’m just like, “Well, I play guitar and it’s fun and my songs are cool.”

ALCOTT: No, I don’t think that’s true at all. When does it come out, the record?

SAVAGE: It comes out in October. I want to say the 6th, but let’s just say October.

ALCOTT: And you’re doing the first show in Paris?

SAVAGE: No. In fact, I’m doing the first show in Portland, Maine.

ALCOTT: I love Portland, Maine. One of my favorite used bookstores is there.

SAVAGE: What’s it called? Let’s give them a shout out.

ALCOTT: I think it’s called Yes Books. I love everything about Portland, Maine. It makes me think of Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, where she talks a lot about visual scope and scale and how the best cities keep secrets. And Portland is a lot like that. You turn a corner and then there’s the bay, and you turn it again and there’s something else entirely. The architectural diversity is so astonishing.

SAVAGE: Yeah, I’ve always been fond of it. When I was 20, I hitchhiked there just because it was like, the furthest I could go from Texas, in my mind. I’ve loved it ever since then.

ALCOTT: There’s so many record stores there. I don’t know why. Their preservation of media is at a high.

SAVAGE: There are some good record stores there. And there’s one that’s been there for a long time and it’s on Congress Street, and I forget what it’s called. Anyway, Interview readers, come see me in Portland, Maine on October 20th at Space.

ALCOTT: I can’t wait to see it. Bye, Andrew.

SAVAGE: Bye.