FACTORY GIRL

Nicole Flattery is Writing Novels for the Losers and Freaks

There is no writer working today whose work makes me feel like Nicole Flattery’s does. I first came to her fiction a few years ago through her collection of short stories, Show Them a Good Time. I was in bed for a week after an abortion which had been a little medically complicated, trying to read. I was angry about the way I had been treated and I wasn’t able to focus on more than a page of anything. I’d bought Show Them a Good Time a few months earlier because I liked the cover, a photo of multi-colored balls, which I felt conveyed a funny, faintly manic energy. I didn’t know anything about Nicole, but that was my ignorance. She had already made a name for herself in the literary world, winning accolades like the White Review’s buzzy short story prize. Anyway, I picked it up and it was the first thing I could read. It was beautiful and funny; she is an extraordinary prose stylist. But what struck me was the way the characters she writes, typically female protagonists in slightly surreal situations, interact with the world. Sure, they are a little unhinged, but the world around them is far crazier, and they aren’t simply going along with it. This doesn’t make their lives better. If anything, it makes them worse. They are deadbeats and losers. But Nicole’s work questions the value of playing a stupid game. What she does is not realism, but to me it feels somehow more honest and true. And that’s what brought me back to life.

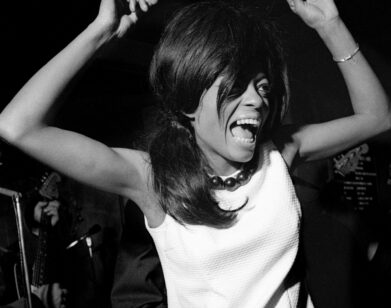

Her first novel Nothing Special, to be published by Bloomsbury next week, is about a pair of teenage typists in Andy Warhol’s factory who transcribed the material for his book a, A Novel and never got any credit. It has a lot to say about art, the deranging effects of fame and celebrity culture, and what social media has done to us all, without being a book in which the characters all sit around on their computers. Because of the setting, I thought this was the perfect place to talk to Nicole about my obsession with her work, and some of her obsessions: fame, ugliness (the word appears 25 times in the book), style, and the often strained relationships between women.

———

RACHEL CONNOLLY: Here we are in the perfect place to talk about your book.

NICOLE FLATTERY: The weather is so good, Rachel, that I could actually talk about the weather for 40 minutes.

CONNOLLY: I was back in Belfast where the nights are even longer and there’s this stretch of five hours where everyone just goes crazy, like on a Tuesday when it’s hot. Everyone’s teeming in the streets.

FLATTERY: Yeah. I just need to stop going into town and drinking four or five rosés every single night. It’s not good for me.

CONNOLLY: Let’s start with the obvious question. Why does Andy Warhol feel interesting specifically now?

FLATTERY: I was initially drawn to the idea of working on a piece of art and your name not being on it, which I read about in The Lonely City. Mae [the protagonist of Nothing Special] is a transcriber, like the women who worked for Warhol. But then obviously, they did get an attachment to the text. And I’m interested in all that work that goes into the idea of a genius. And that’s initially where the idea came from.

CONNOLLY: I like the way the book explores the idea of doing work that you’re never really rewarded for, which is a thing most people have experienced.

FLATTERY: That’s been the predominant experience of my adult life. When I did that event at the London Review bookshop, someone asked about this essay I wrote when I was 25 about working for a literary agent. And she was like, “Did that influence the book?” And I hadn’t thought about that essay in years, but then I was like, “Of course it did.” That’s why I like to write characters who are quite young. You’re just figuring out the world. And that first job, or second job out of college is your first encounter with power and how it operates in the world. I almost think I believe that writers only have one or two topics—

CONNOLLY: Yeah. I literally write the same piece every time.

FLATTERY: I think my obsessions are celebrity, power, what goes on behind the scenes, and the performance of a personality.

CONNOLLY: I love that any way you describe your book, it’s not what you expect. So you could say to people “It’s a book about Warhol and the factory,” but he’s barely in it. Or you could say, “Oh, it’s actually about a female typist,” and that makes it sound like it’s trying to be empowering. I read the book as a subversive critique of this idea of taking back the female artist and giving women their rightful place. There’s that line where Mae’s going around the gallery, and she’s like, “Oh forgotten female artists where they have to wheel out certain books by women, certain paintings.”

FLATTERY: I hate that. And I really didn’t want the book to be positioned as a reclaiming of Warhol or a feminist text or whatever.

CONNOLLY: Yeah, because you could write a really corny book that had Valerie Solanas in it. You could write a version of your book that was so cheesy, like the world if she was Warhol for the day or something. That would be so awful.

FLATTERY: Someone said to me, “I’m surprised it’s not a bitter book.” Because Mae could be quite bitter about this experience, but I didn’t really want her to be. She grows up, and it’s an experience she had, and she put it to the side. But I just find that idea devastating. I think we’re living through a unique period where creative work is being completely dismissed in some ways. Everything creative has to be made using a factory kind of method, and I just found that the saddest thing, the saddest thing I could write a book about.

CONNOLLY: She’s not bitter and I almost read that as the source of her power. That’s what I get from your short stories, too. There’s a thing in your short stories and the novel where the characters are very disenfranchised and they can’t interact with the world really in a positive way. But the lack of bitterness is their source of power, as I see it, because they really don’t care. They’re just like, “I don’t fit in with the world, but that’s not my problem.” It’s not a system they want to succeed in.

FLATTERY: Yeah, totally. And it’s not like they’ve entered the game and lost. They just haven’t entered. It’s not like Mae went into the factory and tried to be this actress or whatever. She’s not riding on Warhol’s coattails.

CONNOLLY: Your work reminds me of Mary Gaitskill’s work in that way that it’s characterized as dark and sinister, but actually there’s such a soft understanding of human beings underneath that. There are parallels between Nothing Special and her book Veronica. But I really like that scene in your book where Mae meets her old friend from school, Maud, who very much played the game and got a rich husband and ascended to this status that society tells you is good. But actually she’s as unhappy as Mae is, and she sees her life as fake, too. And I think your book says something really big about the human condition in terms of how all of the furnishings that you’re supposed to surround yourself with won’t actually give you any more than an alienated person.

FLATTERY: One of my favorite writers is Edith Wharton. but I don’t think anyone would compare our work. But I think what she does brilliantly is she shows how class and certain things in society just hold everyone back. And I love how subtly she does that. I really wanted to include that chapter you mentioned but I wasn’t sure at what point to show Mae as her older self. And that was one that, up until the very end, I was going to cut. I love cutting things. That’s the short story writer in me.

CONNOLLY: That’s actually a really striking element of your writing, especially in the current climate where there’s a death of good sentences. Me and my friends are always talking about this. A lot of work is just very stylistically bland. Sally Rooney gets accused of being bland but I don’t think she actually does it. Your sentences are really striking in that landscape, because they’re so surprising. It’s so rare for me to read a page of your work and not laugh, because there’s always a sentence that starts going in one direction and then ends up going the opposite way. And you have this absurdist way of putting the sublime and the ridiculous together. On a sentence level, do you spend a lot of time thinking about specific words? Do you rewrite sentences, or do you just get a sentence in your head and know that’s the one?

FLATTERY: I think style is everything, isn’t it?

CONNOLLY: People have forgotten that. Books aren’t supposed to have style at the minute. They’re supposed to have morals.

FLATTERY: See, this is the other thing. People have been like, “Mae’s unlikable,” or “she’s frustrating.” But what is frustrating about her? I’m really curious.

CONNOLLY: I think she sits at odds with the current publishing landscape, because the current publishing landscape loves trauma and maligned figures and all of that. [But] I think when people say “unlikeable,” they probably mean that Mae does not go through the journey that they expect her to go through. She doesn’t make her situation any better, she doesn’t emerge triumphant. And she’s a bit deadbeat and never moves beyond that plane. I think that’s the thing that people would presently find frustrating. But that’s what I find very refreshing about her.

FLATTERY: I think it really speaks to people’s relationships with failure. People are so terrified of the idea of failure. To me, Mae isn’t a failure at the end of this book just because she didn’t grow up and have some exciting artistic career. She retained her sense of self, and that is what I wanted for her. She lived through something, and she maintained a sense of humor about it. I don’t know what else is an achievement.

CONNOLLY: You write losers very well. There are people who are unattractive, unappealing, and they behave weirdly. But you’re not a loser. So, it’s interesting to me that—

FLATTERY: I love appropriating losers.

CONNOLLY: Yeah, you’re appropriating losers, exactly. I think when we talk about privilege discourse and so on, we tend to talk about it in identity terms. But there’s other metrics of privilege, like attractiveness, charisma, charm, the stuff that we don’t really talk so much about. But I think everyone understands that that is a form of privilege in the world, and most people see it very clearly in the sense of how they’re disadvantaged by it. Your book reminds me of Star by Yukio Mishima, which is a great book, he’s one of my favorite novelists. [Yes] all of his characters are beautiful—it’ll be a dashing young man who’s terrifically handsome and a genius or whatever. Mae is dumpy and frumpy, and most people would not write a character like that. They just don’t think to do it.

FLATTERY: I met Mary Gaitskill recently. And we were talking about unlikable characters, and she said something that was so profound in such a casual way. She was like, “I don’t know what it means to be likable.” She’s like, “I meet people who are likable by any standards all the time. They’re nice. They’re kind. And I don’t always like them.” I feel the exact same way. There is no “likable” character. I feel like I encounter these characters in fiction all the time that are exactly that. Very handsome, striving, intelligent, thoughtful, all these things. And I hate them. When people talk about likable characters, I lose all interest. If I feel like I’m reading someone trying to that on the page, I’m gone. That’s something I really liked about your book. You weren’t working towards that. Is that something that you deliberately went against?

CONNOLLY: Yeah. A couple of editors who didn’t click with my book said that they wanted my character to have a big emotional breakdown. But she just wouldn’t do that. She has quite a dysfunctional family life, but she’s never really been in an environment where she’s allowed to have a breakdown. I didn’t want to spell out the way that she is.

FLATTERY: Yeah, no. And I don’t think you do. You don’t absolve your main character of anything. That was something I was aiming to do. And I was thinking of books that do that, where you’re with the first-person character and you’re like, “They’re my way in.” Like cousin Greg in Succession. You’re like, “That’s me. That’s what I’d be like.” And then he gets worse, as anyone does as they become more ambitious. But people are very uncomfortable with that. They’re very uncomfortable with someone they once identified with doing something wrong.

CONNOLLY: I think some people sit comfortably with their own badness and some people absolutely do not. At the moment, people are having a hard time accepting that both things exist in every person. It’s funny. I actually never interacted with Mae as an unlikable character. I liked her, actually. So much of what she does is so recognizable to anyone who’s been a teenage girl. She’s buying lipstick because lipstick is what the girls she wants to look like would wear. And she’s a real person who reads magazines. I think many have more Mae in them than they probably want to acknowledge. I think the ugliness in a character who’s not just purely ugly is something people find extremely weird at the minute and discombobulating.

FLATTERY: Someone pointed out how many times the word “ugly” is used in the book. I’m sort of into ugliness. I didn’t want the book to look like the 1960’s fucking Instagram filter.

CONNOLLY: One of my favorite lines in the book was when it’s New York in the present and she’s going to chain restaurants. She’s looking around in this restaurant and all the servers are really beautiful. And she’s like, “It was like there was nobody ugly left in New York.” And I think the book strains against that. Ugliness is celebrated because beauty is conformity.

FLATTERY: With beauty now, I feel that there’s a certain look that’s everywhere. It’s bland handsomeness. But you would never be attracted to that person because they’re not sexy, somehow.

CONNOLLY: Or they’re an Armie Hammer type person. Nobody fancies that guy.

FLATTERY: And then you watch a film from the ’60s and you see the weirdest face you’ve ever seen and you’re like, “I think I love that person.” You’re watching The Sopranos, and James Gandolfini is so charismatic that you’re like, “This is an attractive person.”

CONNOLLY: The book never speaks explicitly about social media. There’s a line I really liked where the main character is sending deranged emails to try and obtain this book she read in childhood. And she’s like, “Nobody wanted to read some deranged person’s thoughts on the computer back then. But that was then.” And that was kind of sly. But I thought, aside from that, the book managed to say much bigger things about social media and fame and attention without directly referring to them, which I really appreciated. I want to read a book that deals with the reality that we live with, but I don’t want to read a book where everyone’s sitting around on the computer. It’s boring to read.

FLATTERY: I was thinking that this book was a great way to explore the way everyone feels about celebrities now, which is deranged. You can feel ownership of someone you follow on Instagram that has 10,000 followers. And then they do something you dislike, or they do something that you perceive to be out of character, and you feel wounded. It’s an incredibly weird dynamic, but I think it is only going to get more interesting to write about, because it’s a bit new. I feel like [the 60s] is an interesting time to set this book in, because the factory feels like the beginning of that type of celebrity. And now it’s just getting more and more intense. I quite like the chaos of the real world. Did you write something about it? The therapy-speak and stuff people use? Like, “You need to remove toxic people.” It’s just like, “Get rid of this toxic person. Get rid of that.” Every relationship is going to have something difficult and messy you have to work through if you actually want to preserve it. I find that kind of relationship to the world really strange and frightening. And the idea of someone sitting in their room trying to control every interaction and every difficult moment that they’re going to experience is so dark.

CONNOLLY: There’s a type of person I always vibe with who’s a bit of a loose cannon, but you know where you stand with them. You know that they’re basically loyal. Whereas I think the type of person that really creeps me out is a very manipulative, controlled person. And that is a type of person that I’m much more wary of.

FLATTERY: That really feeds back into what we were saying about fiction. I think people are unwilling to accept the rough edges of people and characters in fiction. I think sometimes I write these controlling characters, and then things collapse when they lose control. That’s what I’m really interested in. But I wanted to ask you, what are you trying to get at with your fiction that you don’t think you can approach with your nonfiction?

CONNOLLY: With fiction, I get characters in my head, and I want to put them on the page and create them as I can see them. I’m not someone who’s like, “I want to say this specific thing.” I’m more like, “This is a dynamic that I want to push.” I’ll imagine a situation or an interaction will come into my head, and then I’m like, “I want to think about that more. How would those people know each other? How did that start?” But how does your fiction work?

FLATTERY: It’s usually just a character or an idea that I want to explore. And like we were saying, I’m really tired of this victim trauma narrative. I want to get closer to the characters that I find slightly uncomfortable. I’m writing this story now, and I’m really uncomfortable writing it. And I think that’s good, that’s where I should be. Because one of the things fiction can do for me is try and help me understand someone I wouldn’t normally understand. I want to keep pushing myself to do that. All my little losers and freaks, I love them.