in conversation

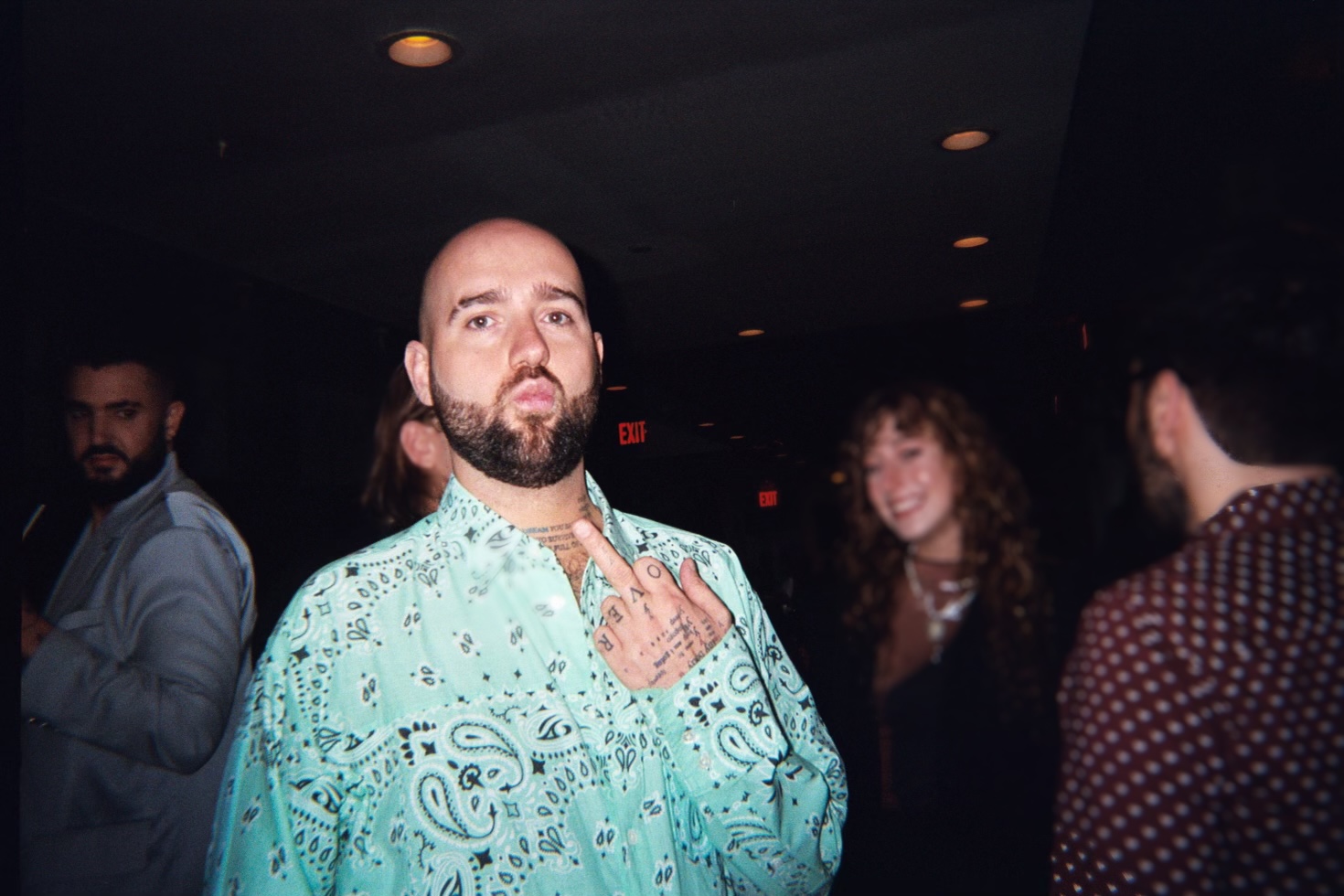

Kyle Dillon Hertz on MFAs, Trauma Plots, and His Novel The Lookback Window

Talking to Kyle Dillon Hertz is a truly astonishing experience, a plunge into a roiling stream of bracing insight, reckless shit-talk, hilarious one-liners, virtuosic profanity, cutting-edge slang, Grade A gossip and heart-rending confession that more often than not leaves you stunned and wondering to yourself what the fuck just happened? When I first met Kyle at the idyllic upstate artist retreat of Yaddo last summer, where we were both doing a residency, I felt the urge to write down practically every other sentence that came out of his mouth in our many after-dinner hangouts, but never got around to it because I was laughing too hard or had had a few too many drinks, or both. Which is why I was very glad to have the opportunity to talk to him for Interview on the occasion of the release of The Lookback Window, his debut novel.

The Lookback Window is also astonishing, but in a different way than talking to Kyle is. It can be shocking in its frank depictions of the abuse older men inflicted on Dylan, the novel’s protagonist, when he was a teenager. But the prose tends to be spare and controlled, humming with a tension that echoes Dylan’s ambivalence as he struggles to decide whether to take advantage of a new New York state law which opens a so-called “lookback window,” allowing victims of sexual crimes to pursue financial restitution from their abusers after the statute of limitation has expired. This a serious book about a serious subject, yet The Lookback Window manages never to feel too heavy. It moves deftly from a remote beach resort to the streets of Manhattan to a dimly lit gay bar to the fluorescence of a psychologist’s office to a clothing-optional Fire Island hotel to a police interview room, revealing new and destabilizing facets of Dylan’s pain and his struggle to heal at each step. It shows Dylan’s trauma in the fullness of his life as a young gay man at the center of a shimmering web of relationships and institutions which simultaneously lift him up and hold him down, and in its sensitive portrayal of the profoundly social nature of recovery and justice, The Lookback Window asks us to consider in all its complexity the question of how we might be able to make a better world together.

———

ADRIAN CHEN: I haven’t seen you in a while.

KYLE DILLON HERTZ: Hey.

CHEN: How’s it going?

HERTZ: It’s so warm it’s shocking. We have two air conditioners running and I still have that nasty fucking New York feeling. What about you?

CHEN: It’s actually beautiful here in California. We had some really hot weather but it’s sort of cooled off. I definitely don’t miss the humidity there. Your book is about to come out and that’s what I’m talking to you about. You were adopted like Dylan, the narrator, right?

HERTZ: Yes. I was adopted, which has all come crazily to a head recently because of the book. My biological family found me.

CHEN: Wow.

HERTZ: It was a long, crazy ordeal. I’d been on Ancestry for a decade, so I knew the names on there because I had reached out like, “Hey, know the missing baby?” But no response. Then because of the book, I got this random follow on Twitter and I knew the man’s name from Ancestry and he messages me with the final sentence, “So you have a book coming out,” which of course turns my stomach.

CHEN: Do you think that’s why he wanted to do it?

HERTZ: I don’t know. It’s hard not to be pessimistic about this stuff. To me, the only thing that’s different is that if you search my name, a product comes up as well as a picture. I talked to him for six months. He basically found out that my biological father was also given up for adoption. Basically they’re a fucking messy Texan family. Literally, what is the probability that as an adopted person, my father was also given up for adoption? That seems pretty fucking rare and weird and bizarre.

CHEN: Well, that’s the thing with all these ancestry tools. People that maybe shouldn’t meet are meeting?

HERTZ: [Laughs]. Long story short, I grew up in Rochelle, you know where that is, obviously. Jewish family, Survivor-themed Bar Mitzvah. I didn’t know any gay people growing up. That’s how I ended up getting into trouble. But all these stupid book bans, it’s been triggering—that response of this world that I’d forgotten existed. The homophobic world that I grew up in still fucking exists and it’s bizarre. Time feels very strange these days because, I don’t know, you feel like a kid again.

CHEN: I also grew up in a small town which was pretty homophobic and I didn’t know any out gay people either. Did you know you were gay at that point?

HERTZ: Oh, yeah. I mean, forever. It feels more bizarre in contrast to today, where every single person I know is queer. You forget just how fundamentally bizarre it is that the world was, allegedly, so different 17 years ago. People were truly closeted. You felt you had to go to these lengths to see other gay things, to feel any kind of connection. But I also didn’t feel bullied for being gay. I feel like a lot of the people that got bullied for being gay were not actually the gay people, but the feminine guys who the world just took a fucking mallet to their souls as teenagers. I fucking hate this world. I’m in a real angry place these days, Adrian.

CHEN: Well, that’s an interesting time for your book to come out, which is also a lot about anger, so maybe it’s appropriate. I read an interview with you where you said you didn’t even really show it to people in your writing workshop, and now all of a sudden it’s out there.

HERTZ: I was definitely right for doing that. People have such shitty opinions, specifically on books. I’ve watched a lot of my friends from grad school never ever get published because they rely so much on the adoration of people they respect, and it’s not good. The weirdest part about the whole thing is that I wrote this book while I was in treatment at the Crime Victims Treatment Center. So I wrote this book in therapy with a therapist who specialized in trauma. So in some ways, yes, I did completely write it when I was alone. I feel like I had this extraordinary experience of getting to work through not only my violent sexual trauma with a therapist, but then the process of creating art with it. I sent him the book, we met, and we talked about the book. He read it and he talked about his experience with the book. So, really, I had a perfect experience writing it. I feel like I’ve made my peace with it. I had a moment of real fucking shock and terror when I saw this person from Publishers whatever.

CHEN: Publishers Weekly?

HERTZ: Thank you. There’s something fundamentally fucking bizarre about seeing your life spit out through someone else’s words in a way that feels trippy, weird, and uncomfortable as fuck. Do you know what I’m talking about?

CHEN: Well, I’m a journalist, so that is often my job—to do that for other people. I know how bizarre it can be. It’s a bargain. It’s a trade. You’re saying, “Well, you’re going to print my words to people that I would never reach otherwise or help me sell my book. I’m going to give this up to you and you get to do whatever you want with it, really.” Which is sort of the opposite process of the novel, where you’re trying to shape your own story in the most direct, immediate way possible. I was reading an essay by Jonathan Franzen a while ago, and he was sort of poo-pooing the idea of literature as therapy. He was like, “I don’t want my books to be therapeutic.” But in your case, it seems like it was part of your therapeutic process to write this book. Would you say that’s true?

HERTZ: Yeah. I think I was reading that same essay yesterday because I went on a Franzen kick—first I was listening to his podcast talking about characters as objects. Was it part of my therapy process? Yes, it was because I was going through that program when I was in grad school, when I was writing the book, while I myself was fucking tracking down the men who raped me. So yes, it was absolutely a part of it. I think for me, the character of Dylan and myself are very different. It was therapy in the sense of giving me a comparison point for my own experiences. It gave me this unvarnished psychological object that I could essentially just scream into, because you can’t go around screaming through the streets. That was a great place to create art and a great place to put some of the things that I’ve been thinking of somewhere else rather than just my own shitty little mind.

CHEN: Mm-hmm. At the end of the book, the character is saying what they wanted with the book, which is to show a path towards healing and also to talk about how to say the unspeakable. Do you have a similar sort of hope that this will pass on that same kind of healing to other people?

HERTZ: I do hope that, of course. I’ve met a lot of other cis, straight men who were molested, assaulted— gay and trans men, anything. I’ve met a lot of people in rehabs and facilities who really have no language for this. And that’s terrifying to me because I know the feeling of not having a language for what’s bothering me. It almost ended my life many times. When you don’t know what to say, you have to act. And I think it was important for me to be able to be as honest as I possibly could as a writer. And also to allow Dylan to be as free to say whatever he wanted to say because that can be very liberating. The book does position different pathologies for healing or methods for healing. There’s like five or six different ways that the men in the book try to deal with what they went through, whether it’s Moans or Alexander or James. I wanted the characters in the book to say whatever they wanted no matter how uncomfortable it was. Because that is truthfully, I think, what liberates other people.

CHEN: Were you always a writer?

HERTZ: No. You know damn well I went to fucking massage school. My plan was, honestly, to get into porn because I bombed high school. I went through horribly violent sexual abuse as a teenager for years. I moved to California the day that I graduated high school, which for me was summer school because obviously I failed the regular one. I would’ve killed myself in weeks because of the psychic pain that I was in. Again, I didn’t have the language. Now I can say, “Okay, well, between the ages of 14 and 17, I was pimped out, trafficked, and people took child porn of me, which they paid for in drugs.” That language I have now is very freeing because it means I can let it out. It means I know where to point my anger. And when you don’t have the words for it, you point that anger almost at yourself because you don’t know where it goes. I would’ve made a horrible massage therapist. It’s literally the world’s worst A24 kind of gay PTSD movie.

CHEN: Did you read at the time?

HERTZ: Yes, always. I actually don’t think I’ve ever talked about this before, but when I would be in the specific person’s house waiting for the bad thing to happen, I would read. This is going to choke me up, but I can remember the books I read back then so clearly because I was so fucking afraid of what would happen to me. There was a stack of books, some of them were just dark-sided stuff that I’m not getting into that I was given in order to groom me, and some of them were just things to escape.

CHEN: What was one book that made an impact on you back then?

HERTZ: I honestly hate that I’m going to say this, but Into the Wild made such a huge impact on back then, which makes sense if you think about it. I was obsessed, of course.

CHEN: It’s like a fundamental adolescent fantasy, right? Even if you’re not being abused.

HERTZ: Literally. I mean, I love that fucking book. That was a great one.

CHEN: That’s a great book. Did you read the New Yorker article where [Jon] Krakauer had this new theory about what happened to him?

HERTZ: No. What is it?

CHEN: I’m going to get this wrong. He basically thinks what happened to him was that during the winter he was eating some sort of berry or something to subsist. This particular berry can cause your nerves to seize up. Basically, he has this whole theory that he was subsisting on this berry that slowly poisoned him—he couldn’t walk anymore, and then he just was too weak and died. I love that book as well.

HERTZ: Did you have a book when you were a teenager that just…

CHEN: Really hooked me? Let’s see. I feel like I was really into The Great Gatsby, weirdly. When we read that in high school, I was obsessed with New York and I thought that it created such a mystical but sort of sinister portrait of it. I grew up in Vermont, which is this very idyllic place. So I think we had that sort of dual fascination and fear, but it was never really presented as anything but just a foreign land. That sort of grounded that fear. I liked that a lot. What was San Diego like to live?

HERTZ: It was honestly great. The nude beach—I mean to go from feeling like you didn’t know any gay people to being hot and 18 at a gay nude beach, it was amazing. To work a restaurant job, this place called Extraordinary Desserts, where we would get high in the parking lot and then end up at the beach.

CHEN: That’s such a San Diego name.

HERTZ: It’s so good. I’m trying to drag my husband there when we go next month because we’ll be in California. It was great. It was different than New York. I got to restart my life completely. For a while, I felt like I could do anything I wanted. And that, honestly, is what got me here.

CHEN: How old were you when you started writing?

HERTZ: I was 19 and I took adult education classes through UCLA extension because that was the only option. I was just like, “I don’t love massaging these men. I don’t want to do porn, that doesn’t seem like restarting my life.” I wrote some story, and like everyone else, sent it to the New Yorker, who wrote back and said, I’m paraphrasing, “You’re talented, go to school for writing.” Which is literally what I did after that. I was like, “Okay, fuck it.” That brought me back to New York, and I had enough adult and community education classes to transfer to The New School.

CHEN: That’s very old school, getting the encouraging New Yorker rejection. What did you study at The New School?

HERTZ: The one and only thing I can do, which is writing. The truth is a lot of people joke about being only good at one thing. I was probably in high school for 120 days over four years. I failed everything. Whatever fucking nasty awards they give you for not showing up, that was me. I can’t do math. I can’t do science. I have no brain for anything other than writing because the only thing I did was read.

CHEN: How did you end up in an MFA at NYU—that’s where you went?

HERTZ: Yeah, I got in and I needed money and they gave me a good scholarship. The truth is, once I made that decision to start writing this, I was going to make it happen. I just had to make it happen because I was so behind other peoples’ paths. I had an older husband, we were not meant to be together. The thing that NYU granted me was the money, which also allowed me to get divorced.

CHEN: And what was NYU like? In the novel, Dylan is pretty negative on his program and classmates.

HERTZ: I had a great time there because I like to have fun, so I made friends. Some of my closest friends are from there. The teachers, like John Freeman, are extraordinary. But there were such unbelievable assholes. It was my first time ever encountering naked, full-blown fucking money. It was the first time someone has ever said to me, “Oh, I don’t ever have to work in my life if I don’t want to.” And I guess it was also one of the times that I started getting lied to about money. I recently discovered this friend from the NYU MFA program, who’s been pretending to be kind of poor for years, is actually fucking loaded. In some ways, it was my first adult experience with being swindled by people you would otherwise call your friends. I hated about half of them. I think I only hate about a quarter now. Time has made a few of them nicer to me. But there were also barely any gay people.

CHEN: Tell me a little more about the process of writing the book. How long did it take?

HERTZ: Truthfully, about a year. A draft took about a year. I wrote a shitty book my first year, and was kind of talking to agents, but nobody really liked it. I’d been wanting to work on this other thing. Once I started going to treatment at the Crime Victims Treatment Center, I really started going in on the book, which basically landed my second year at NYU. Because in my own life, I have the Child Victims Act structure of, “Kyle, you have one year here to decide whether or not to bring a civil case against your abusers,” the people who raped me when I was a kid. Adrian, my life immediately fell into just this kind of organized situation.

CHEN: So the Child Victims Act was the sort of motivation for you to start this second book?

HERTZ: Yeah, I think it gave me a structure. Not that I wanted to write about myself, but I’d wanted to write about things I liked, violence, sex, drugs, gay people, drama, humor, stuff like that. But the structure came with the law because it’s hard to write a novel, but once you have a structure, you can fly through it.

CHEN: I mean, it’s a very dramatic thing to all of a sudden be like, “Okay, you have to now decide if you’re going to confront this horrible thing that happened in your past.” I felt like it really grounded the book in the social and political context of the time, right? This is a new way of approaching victims and abuse, realizing the complexities of that process. The other thing that I appreciate about the book is that, while it’s obviously about trauma and the psychological impacts of it, it’s also about the social world of what that means. Dylan has to go through all these institutions, the police, the therapists, the lawyers, so you sort of see this larger world and it’s very even-handedly depicted. It’s not super critical, even though it’s failing all the time and absurd in other ways. But it does seem like Dylan gets real help and care. I’m curious about your own experience with the institutions that have been set up to care and find justice for victims.

HERTZ: With CVTC, I had an extremely positive experience. I gave one interview for this book early on where someone asked me a similar question. I realized that I was quite ignorant outside of my own experience. So I reached out to the Crime Victims Treatment Center and said, “Look, I was asked this question that I don’t have a good answer for because I had such an extraordinary experience where I got to be treated for childhood sexual trauma for men.” When you hear people talk about PTSD, it kind of feels like eye-rollingly permanent. It feels like culture likes to talk about PTSD, violence, and sexual abuse in these ways that aren’t that helpful or real. It turns out, actually, that the country as a whole has programs in every state where, if you are the victim of a violent crime, you can call up the rape center and ask, “Okay, where can I go?” And within two hours driving distance there is a trauma treatment center where you will be treated for free if you are the victim of violent crime. That, to me, is extraordinary. I was surprised that I hadn’t heard of it until I was 29-years-old. That would help a lot of people I really care about, and the fact that it’s not part of our culture makes me pissed. What are we doing? It’s annoying. It’s frustrating.

CHEN: Your book is about trauma and that has become sort of a cliché in literature and culture. Is there another depiction of trauma in fiction or in movies that actually resonate with you?

HERTZ: There’s this book Post Traumatic that’s pretty good. The Recovering, by Leslie Jamison. That’s not really about trauma, per se, but that is a really interesting book that gives 100 different ways to deal with alcoholism or drug abuse. I will say, I absolutely hate most books about stuff like this. I mean, the way that people use trauma as a plot device is disgusting. It’s so whack.

CHEN: I’ve had a realization reading a lot more contemporary literary fiction in coming to understand literary fiction as a genre, just like crime, fiction, or horror. There is a pretense around that, and I think trauma is often used to give literary fiction a heft and seriousness.

HERTZ: I think you’re 100% right. That’s so smart. I think you’re dead right.

CHEN: Well, I’m glad you think I’m right. I just wanted to ask you this. One of the things I took away from our experience at Yaddo was your Lana Del Rey fandom. Actually, today, I walked by this bumper sticker on the street where my office is, and I wanted you to react to it. This is a real bumper sticker. It says, “There are two kinds of people in this neo-feudal free fall: those who realize Lana Del Rey’s recent There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Boulevard is the single greatest piece of American art since Steinbeck’s East of Eden, and those who are living in oblivion or denial and must be baptized in the sonic founding of truth immediately.”

HERTZ: I think that might be my friend Michael’s bumper sticker. I’m pretty sure.

CHEN: I have not listened to that or read the book, so I can’t really say if it’s true or not.

HERTZ: Let’s be clear. Lana Del Rey is America’s greatest living writer. Even the great writers, she makes them look like shit.

CHEN: What is the source of her greatness?

HERTZ: I have no idea. Sometimes, people are able to take all of culture and put it into one thing, which is actually what I tried to do in my book, honestly. I think that is what she does very, very successfully, and which I hope to do as well.