IN CONVERSATION

Johanna Hedva and Maggie Nelson on Kink, Capitalism, and the Hope-Doom Binary

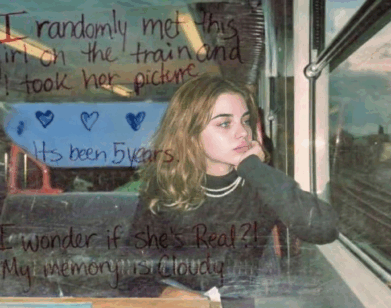

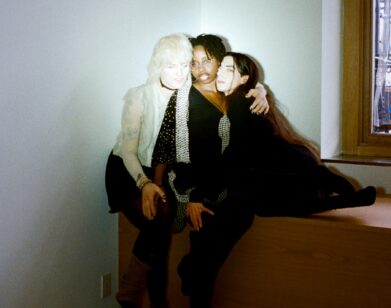

Johanna Hedva has conquered many disciplines: they’re a multimedia artist, a writer, a musician, an activist and, sometimes, a dominatrix. But perhaps their greatest achievement is bringing a polyphonic “we” to the often inadequate discourse about ableism. Their latest essay collection, How to Tell When We Will Die, published earlier this month, invites the reader into an ecstatic circle dance in order to generate expansive approaches to talking about disability, illness, care, sex, and community. “I’ve started to say that in some ways my project is very simple,” Hedva told fellow writer Maggie Nelson over Zoom earlier this month. “It’s just that I wanted disability to be complex.” Coincidentally, Nelson taught at CalArts while Hedva was a student, though Hedva confesses that they could never wake up quite early enough to officially sit in one of her morning workshops. In conversation, the two made up for the lost time, careening passionately between subjects from literary daddies and disability archetypes to the erasure of kink and BDSM in the history of revolutionary movements and, finally, the necessarily performative nature of the essay form.—LILY KWAK

———

JOHANNA HEDVA: Thank you for doing this with me.

MAGGIE NELSON: I am totally delighted. I love this book and I love you. This is a book of individual essays, and I’m fascinated by how you’re able to both introduce and explain concepts to the reader in a very accessible fashion without the book feeling dumbed down in any shape or form. I was curious how the process was for you.

HEDVA: Thank you. That’s definitely something that I thought about a lot. I started writing Sick Woman Theory in 2014, and it was the first time that I had not only really thought about some of these topics, but written an essay in a classic form. It was so astonishing when it was published in 2016 and had a viral online moment because, for so long, it got rejected outright everywhere for about a year. I was like, “This is not really a subject that people relate to or want to read about.” And then when it finally did come out, a ton of people were like, “Oh my god, I really relate to this.” There wasn’t a huge response from the publishing world, but I knew I wanted to write a book someday. I do remember feeling very strongly that what I was doing was not an illness memoir, but an analysis of ableism. I was like, “Maybe it’s like an Anne Carson book on ableism, or maybe it’s like a Sylvia Wynter chapter here, and then Jacqueline Rose chapter here,” in terms of voice and style. When it started to proliferate into possibilities, I was like, “Oh my god, I can have all these different approaches and topics.”

NELSON: There’s this exciting moment in the essay on P. Staff, and also the Sontag essay, where I was like, “Oh, these are just essays about rad people and totally fascinating thoughts.” I wondered if you chose the topics because of the frame, or whether you’d written different pieces for different reasons and then saw the frame as a principle of inclusion?

HEDVA: It was more the latter—I would start to feel antsy and a little claustrophobic, and then I would put the piece aside for years and write about something else. I got commissioned to review the Sontag biography and, as I was getting into it, I thought, “Oh my god, this is a set of topics that is really in line with some of this thinking.” I’ve started to say that, in some ways, my project is very simple: I wanted disability writing to be complex, to find ways to give it more space, more meaning, more range. At some point while talking to my editor, I was like, “There has to be an entire section on sex and kink; multiple pieces, multiple scenes, multiple characters,” because I wanted a book on disability to have a section like that. There were so many essay collections I’ve been influenced by and return to often, and a lot of them are like this. Elizabeth Hardwick’s Seduction and Betrayal is a major influence with what she was able to do in terms of range. She’s one of my all-time favorites. Also Jacqueline Rose’s collections. I was so happy to see your piece on her in Like Love.

NELSON: It was really special to get to talk to her. I felt like this when I was putting together Like Love. As a younger writer, you write about and towards these people who have meant so much to you. And then, if they’re still alive, your writing takes you towards them in this really amazing way.

HEDVA: Your work has definitely been squatting on my shoulders for so many years. What I love about writing and why I’ve always identified as a writer, even though I move in a lot of different genres or have a cloven hoof in the art and music worlds, is that I just love watching a writer do stuff on the page: think and feel and live on the page. I read you as a very young person. And then I was at CalArts over 13 years ago when you were teaching there. It was so funny because when you came to my birthday and you gave me that stack of books you were like, “I don’t know if you have these,” and I was like, “Of course I have these, and they’re underlined multiple times.”

NELSON: That’s so funny. But you were never in a workshop of mine.

HEDVA: No, because they always happened too early. I tried to sign up for one, but it was at 9:00 AM and I couldn’t wake up early. It was such a funny reason to miss a legendary class. But anyway…

NELSON: Oh, I sincerely doubt that you missed any legendary classes. But it’s a weird thing, this nexus of art and literature. They don’t know each other all that well. There are some people who do a lot of crossing, but there is definitely a critical mass in the literary world who don’t really traffic with the art world. I remember when The Art of Cruelty came out, The New York Times put a picture of Chris Burden in the crucifixion piece on his VW bug on the cover, which was weird because I never wrote about that piece in the book.

HEDVA: I feel the same way. The art world’s got all of this chicanery and nefarious ethics and fucked up capitalist exploitation and blah, blah, blah. But then there’s just a bunch of really interesting genius freaks in there that are some of the most open people.

NELSON: I have a lot of notes on this, but I’m going to keep it to myself.

HEDVA: I do, too.

NELSON: I also have a lot of thoughts on neurodiversity, and the literary world’s relationship to it, reading and writing being the main modalities by which it shows us up, which are also very normative skills that the world demands of you. I have mixed feelings. I feel like the literary world has a harder time assimilating the fact that there can be a wildness that doesn’t come from its most normative structures. In art, we know that already.

HEDVA: Yes, I totally agree. I can say at this point in my trajectory that I’m really happy that I’ve not been accepted anywhere. I kind of prefer it. I realized at some point that I would like to have enough fluency in the language of a particular land to order what I want at the restaurant, but I don’t necessarily want to live there. The literary world, the art world, the music world: these are places I quite like to travel in, but I don’t want to belong. And I feel like all of my favorites are like that. This is one of the reasons why I love Deborah Levy so much and why I devote so many pages to her at the end. She’s somebody who we’re watching get better with every book, and she’s been publishing since she was in her twenties.

NELSON: I hear you when you say you feel you are not accepted, but I also want to say, “Watch out.” Because there’s this weird thing where what you think of yourself and what’s made of you by other people is sometimes synonymous and sometimes not.

HEDVA: You said something to me last year that I think about all the time. It’s some of the best bit of advice I ever got. On the day that my novel was published, I went to your and Harry [Dodge’s, Nelson’s partner] house. You guys were like, “Take some seltzer for the road, you’re going to get dehydrated.” I was about to embark on the book tour and you said, “The public is very good at beholding you, but it cannot hold you.” I’ve thought about that so often since. I feel like with some of the topics I’m tackling in this book, like illness and vulnerability and disability and death and all of this stuff, it’s like I’m reaching into some of the readers’ most raw places and I’m like, “Hey, let’s go here together.”

NELSON: I can imagine that you’re pushing a lot of the conversation in ways that would probably make some people feel ecstatic and other people feel uncomfortable. And you do have an affinity for the “we” and a kind of rousing communal language that I’ve never tried on. I’m curious about how all that goes for you.

HEDVA: This is a question that I think about all the time because it’s almost paradoxical, like two opposing facts I have to contend with. On the one hand, yes, I was totally isolated, I didn’t belong to any kind of disability community at all when I was writing. And then they literally came and got me. They sent me DMs and emails being like, “Hey bitch, why don’t you show up at our meeting?” And these were all people that had been disabled for much longer than I had and were active in disability justice activism for years. And then on the other hand, there were all of the worst parts of having a little bit of visibility where I was getting trauma-dumped on by strangers and it felt awful and I couldn’t handle it, so I kind of disappeared. That’s one of the things that is really at the heart of a lot of the questions and ideas I’m trying to deal with in this book, how community is a really thorny thing. As you too have written, care is a really messy task; it’s something one does, and it’s full of ethical conundrums and ways that it goes wrong and ways that it feels bad. So the “we” that you’re talking about in the book, it felt fantastical. It felt like, “This isn’t here yet, but what if it was?” There was always an imaginative speculation of, “What would happen if we were all working toward a sort of world where care was supported and prioritized, where bodies that were malfunctioning or deviant in some way were not punished for it?” In meetings with my publisher, I would say, “I would like us to be prepared for this book to piss people off,” because what I hope is that we can get to a place where there are multiple disabled voices that people are thinking about and listening to and engaging with, and some are in agreement with each other and some are like, “Actually, there’s this other thing to consider.” I would like there to be more complexity. I’m hoping that if I’m pissing some people off, it furthers or makes more room for discourse.

NELSON: I think it really, really will. When I grew up in the ’80s in San Francisco, then the ’90s in New York, it was the age of AIDS, and issues around kink and safe sex and self-care in the community were the fire in which we were all forged. I have noticed that BDSM and kink has always been a third rail for certain writers or thinkers, like Andrea Dworkin. There’s a long history of it. But watching this really interesting and messy last 10 to 15 years, and trying to kind of stay oriented around some of the lessons that I felt weren’t important to me, I believe that they actually were true lessons. Those lessons had to do with what you talk about, the well-built care networks that usually make constellations around criminalized activity or so-called deviant activity. We really lose a lot by not focusing there. These are the kind of things that are really hard to do in a tone that expresses no condescension and no snark and keeps our eyes on the prize.The prize might be a really messy prize, but I really feel like your book does that. The world is full of people who get off on bad faith disagreement, but your book does not in any way set the stage for that. It sets the stage for us all to think and talk and wonder and remember and project into the future and think about our lives.

HEDVA: Oh, I love that. It’s been funny, because in some of the very first pre-publication reviews, the writers said that my book is a hard read in some of the kink essays because I’m making this connection between the physical abuse that I suffered as a child at the hands of my mother and then now, as an adult, my preference for masochistic sex. And I was like, “Excuse me?” I like to punch men, but this is different. It’s a very important difference. That’s not the same as a masochistic sex kink. And also, I’m the top, I’m a dom, and I used to be a professional dom. Maybe it’s hard to reconcile, having a figure that starts the book as a sick woman and later, that character is in a position of committing consensual violence upon someone for pleasure when just a few chapters ago they were taken as fragile and vulnerable and couldn’t do anything. And I feel like kink has been erased or not talked about as being something we should include when we’re talking about our revolution. But in disability, kink is really important precisely because of this discussion around consent and the body and what one can do with the body, what states of extreme pain and duress it can be put in.

NELSON: Totally. And you really take the top off the pressure cooker of all these narratives and let us be in these places without these narratives that discipline our experience and make us think that we have to know where it’s going.

HEDVA: Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore is fucking great at this, where she’ll build an entire paragraph and then at the end she’ll just be like, “Or not, or both, or more,” where there’s this capacity that just keeps getting bigger. I really do believe that the point of meaning is that it can change. As a writer, I want to find all these ways to consolidate meaning in some way and then see what happens if I change this word or punctuation mark, or make this period into a question mark, because then you really start to see what language creates.

NELSON: You and Eileen [Myles] are really great at this. I think it has to do with a certain trust that the writing is performative and not set in stone. You can really believe what you’re saying in the moment, but you might not believe it in the next paragraph or in 10 years. And there’s no problem with that, but it doesn’t stop you from making some real sailing statements. I really admire that sensibility because it feels like the writer is alive with us. I was moved to tears in the first essay when you say, “I don’t know how to do this,” and then you say, “Let’s do this together.” I felt like that was the utopian aspiration. And in my case I was like, “Okay, I’ll join you.”

HEDVA: Well, some years ago I didn’t believe in hope. I thought there was a hope/doom binary that we were oscillating between as a society, and I started to be like, “I don’t know how much use hope is here.” So I started to be like, “Okay, what would happen if we started with doom? If it’s not a place to end, if it’s not looming on the horizon as the worst thing that could possibly ever befall us?” What if we’re like, “No, we’re doomed, and the end is already happening, and for some people, it’s been happening for decades and centuries,” right? In all these years of activism, it’s helped to come at it from that place. This is a bell hooks idea: start where you are, right? My Korean grandmother was Buddhist and she had a Buddha statue in the room and it was one of the religions of my childhood. Also on her side of the family was Korean shamanism, which uses a lot in Buddhism to talk about how we work with the suffering of our ancestors.

NELSON: It’s interesting to me because I do think that there are many different registers for talking about the same thing. But in many, many cases, they converge on similar things. A Christian frame would be, in a way, resurrection is hope, the afterlife is a hope. But it’s still kind of putting on this frame. So in that way, I was really moved by your introductory essay about what ableism gives us. Your tone is more curious, and it’s a little bit pissed.

HEDVA: I love that you called me “pissed.”

NELSON: It’s not angry. “Pissed,” to me, is more performative; it’s a willingness to let yourself kind of channel your rage.

HEDVA: In my experience, ableism is much worse than the actual disability, even though the disability can really suck. It’s the way that ableism makes you feel about it. I tried to say this in one of the pieces: I’m not trying to tell you that if you’re disabled but you just love yourself enough, it’ll be alright. I’m trying to say that you can think about how your disability is actually different than ableism saying you should hate yourself because of it. But I completely understand why it’s hard to get out from under that value system, because it’s in everything.

NELSON: Fred Moten has this line,”Don’t let the document be more important than the practice,” which I love in many, many ways.” But to be honest, I’m a realist about the document and I don’t have a “practice.” I mean, I have my life, you know what I mean? I remember Carolee Schneemann, when I was writing the profile on her, she was just like, “Why does everyone in art call what they do a practice?” She was like, “I hate that word. If you ever say that word, my head blows off.” And if anyone had a life practice, it would certainly be her, but she just couldn’t stand that word.

HEDVA: I adored your profile of Carolee Schneemann. I love so many paragraphs that you have about how close art can be to garbage.

NELSON: Yes, a very underrated and constant thing, especially if you live with a sculptor, as I do.

HEDVA: I mean, I’m just up to my goddamn tits right now in shit like that, because we had to move everything to London to do this show.

NELSON: It’s like, you put the art in a galley and then the minute it comes home, it’s potentially garbage because… where the hell do we put it?

HEDVA: Yeah. My gallerist is literally emailing me like, “Okay, so the hair from that one piece?”

NELSON: Exactly.

HEDVA: I was just very lucky to have this brief window of time with Fred Moten while I was working on the follow-up to Sick Woman Theory, which is In Defense of De-persons. When Sick Woman Theory got published, I suddenly started to critique the manifesto as a form at all. And Fred just really lovingly eviscerated this sort of idea. He was just like, “You made a new cruel optimism with everyone now feeling like, oh, but I’m a sick woman, so that consolidates my identity somehow.”

NELSON: All consolidated identities are like an illusionary, momentary thing anyway. It’s really a gift of the book, too. It has a mental value that isn’t the end-all be-all, or a stopping point. And on a literary note, the writing about your trip to Greece, the essay on Sontag, they’re absolutely phenomenal. They’re some of the most enjoyable and interesting and unusual pieces that I’ve read.

HEDVA: Thank you so much.