ONLINE

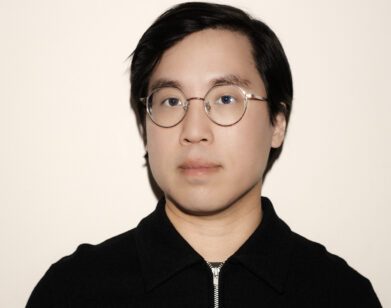

Jeremy Gordon on Media Jobs, Male Loneliness, and Modern Malaise

Is there anything more embarrassing than starting a podcast? Maybe just promoting your own—rate, review, and subscribe to Limousine wherever you get your podcasts!—but I digress. In Jeremy Gordon’s excellent debut, See Friendship, cringe provides ample fodder for a satire of work and life in media right now. After years of writing and editing for culture publications like The Outline, Pitchfork, and Spin, Gordon has turned his talents to the form of the novel, chronicling the misadventures of Jacob Goldberg, a disaffected millennial media worker with a mild nicotine addiction trying to save his career by launching a podcast investigating the tragic death of a dazzling high school friend named Seth.

It’s not all a cynical ploy to make his name; Jacob really wants to know how his friend died so suddenly and so young. Was there foul play involved? And were they even as close as Jacob remembers, or does everything just glitter gold in memory? Along the way, he excavates the days of Julian Casablancas and Facebook albums with red Solo cups, taking stock of the false promises of the post-9/11 era and the hope-y, change-y years that followed. Try as he might to play the witty, detached punk or objective, responsible reporter, Jacob wears his heart on his sleeve, reconnecting with old flames and revisiting old assumptions in his quest to tell Seth’s story. Maybe, it turns out, the real podcast is the friends we make along the way.

———

LEAH ABRAMS: First, I love the book. It’s so funny. I read it on my phone because I got a PDF, and I hate reading on my phone. But I was able to do it with your book because it almost felt like—you know when you get in a Wikipedia hole, reading the digital archive of a stranger’s life? So I wondered if you could share how you approached writing this book about the digital archive of our lives.

JEREMY GORDON: Well, I came of age, so to speak, when social media was just really taking off. I was in high school when Facebook started. I was in college when Twitter started. I used LiveJournal and Xanga as a teenager, and then sort of graduated to using Tumblr as a young adult. At some point, I turned around and sort of realized that I had informally chronicled a lot of what was going on in my life through these digital mediums. It was a lingua franca at the time. You had to adopt it. It’s not like it is today, where you don’t know a world without it. I remember being in high school and starting to use some of these platforms. They were a little janky, for lack of a better word. When I was starting to write the book, I was very conscious of the fact that familiarity with a digital world is second-hand nature to so many people in my generation and the younger generation. In particular, I was thinking about the so-called phenomenon of the “internet novel,” which can be quite wonderful, but goes into the very microscopic, granular nuances of how people use social media. What I was thinking about, in fact, was sort of the opposite thing: people’s relationship to the internet when they don’t think about it at all. There is an obsessiveness to it, the modern conception of being online. It’s not that I wasn’t interested in that, but I was really trying to capture someone who doesn’t think about it.

ABRAMS: In a lot of the so-called internet novels from the past few years, you go into a tunnel of the internet and memes, but your book is almost the opposite. The internet funnels the reader out into the rest of the world. I thought that was really well-done.

GORDON: Thank you.

ABRAMS: The book’s in first-person, which plays a part. It’s easy to fall into navel-gazing territory, but you take it in a much more expansive direction.

GORDON: Yeah, I often enjoy novels where you’re charmed by the voice of the narrator and yet you have reason to doubt him. I think my protagonist is a funny, charming guy, or at least he presents that way. He seemingly has these deep thoughts, but he’s also fallible. It’s not a coincidence that throughout most of the novel, he’s just sucking on a vape pen. This guy is just kind of obsessed with his thoughts, and that is certainly something about a writer who is friends with other writers, many of whom are on social media. It’s very easy to fall in love with your own thoughts.

ABRAMS: 100%. You brought up the narrator’s fallibility, and without giving any spoilers, this is a book that’s very much about substance abuse. It plays a role in the narrator’s personal journey—whether he acknowledges it or not. How do you approach writing about substances, and how did they play into your characterizations of different people?

GORDON: Well, similarly, I’ve known many people who’ve had different relationships to substances in a very casual manner. Something that’s difficult to articulate when you’re a teenager and young adult is, you don’t know when you have a relationship to substances. It’s sort of couched in the language of going out and having a good time. I think sometimes you need the distance of not being inside of the thing to realize that you were, in fact, inside of the thing. I never want to be judgmental of how someone spends their time, but that sort of informed some of these characters and their casual relationships to drugs.

ABRAMS: Absolutely. One of the other things I really loved about the novel is the way it speaks to the male urge to start a podcast. Here’s this protagonist who’s struggling to find connection, but also has a lot of really rich friendships. And when he reaches out, he’s met with support and love.

GORDON: Well, it’s funny, ‘cause at the start I didn’t think I was writing about friendship, which is ironic given the title of the novel and where it ultimately goes. I was just thinking about people in my life who meant a lot to me. I’ve been very fortunate to have some very strong male friendships with people who encourage a sense of openness. I think simply being honest about where you are is half the battle in terms of the so-called male loneliness crisis. And believe me, I’ve had plenty of male friends with whom it is a thinly veiled competition, as opposed to a more charitable exchange of ideas.

ABRAMS: There are examples of both in the book, but I especially love the ones that are genuine relationships. That brings me to Seth, a character who makes up the heart of the book and is the impetus for the protagonist to start the podcast in the first place. Could you talk more about how you came to that?

GORDON: It’s crucial that Jacob meets Seth when he is a freshman because Jacob looks up to Seth as someone who has everything figured out and knows the lay of the land—which is, in fact, the tragedy of their relationship. He has a very partial view of what is ailing his friend. There’s a whole world that he’s just not privy to, whether that’s because their relationship isn’t that close or they’re not good at talking about these things. You’re at this age when you don’t have as many experiences, and even just one positive interaction could literally change the trajectory of your life. Sometimes it takes the distance, the literal passage of time, to be aware that it’s almost a miracle you interacted with this person. But you also try not to write about them in a gauzy way because the flip side of that is, it’s very sad to only see the part of someone’s identity that they’re comfortable showing you. There’s a tragedy in being repressed or secretive, to not have the luxury of self-expression.

ABRAMS: One of the things that really draws them to one another is being biracial. I wanted to hear a little bit more about why that came through for you for these two characters and how you approach writing about identity more broadly.

GORDON: Well, it’s true that there’s so much media about being biracial that is extremely corny and extremely uncool and very literal. Being biracial myself was not something that I interrogated too deeply until I was older. I certainly had experience existing in two worlds—as I say it, it is very hard to avoid the cliché of “one foot in one world, one foot in the other world.” I thought about the casual way of writing about it—acknowledging it but not lingering on it too much. The book is set in Chicago, where I was very lucky to have an upbringing that was a truly diverse environment, racially and socioeconomically. It wasn’t really remarked upon, it was just kind of a fact of life, particularly when it came to racial identity.

ABRAMS: Perfect segue to Chicago, which is the hometown of all of our main cast of characters. Why did you decide to set it in your own hometown?

GORDON: To me, it felt like a place where the problem certainly hadn’t been solved, but there was a sense of the hope and change of the Obama era. I went to a high school that was, racially speaking, 30% of everything, and everyone more or less got along. There was a sense that this is what a multiracial city governed by progressive social politics could look like. Then you get a little bit older and you realize it’s not. But everyone I know who’s from Chicago fucking loves it, and it’s not because they love the Bears or The Wieners Circle. I think it’s because they had the wonderful experience of growing up in a cultured city that was not governed by status or social positioning. Of course, I’m saying this with a lot of fondness, but I do think it is true that there was something idyllic about the upbringing I had but which now seems so very far away. I saw it as the breeding ground for a lot of my ideas, particularly how these characters move through the world. They’re very comfortable being in a room with people of all stripes, and I’m very grateful for it. When it came to recreating how Chicago felt in that era, a lot of it came back to me the minute I needed to think about it. We’re now able to easily recapture things by going on Facebook to remember how people were dressed or the bands from that period that you can just queue up instantly.

ABRAMS: Obviously, the process of writing a novel is very different from your day job as an editor. How did you take off the journalist hat and start writing fiction?

GORDON: This will sound very stupid, but I’m a long time fan of books, and my reading diet has never been particular, one way or the other. I got into journalism almost off of a whim. I had done it in high school, and then I applied to journalism school, not because I was obsessed with being a great journalist but because it was just the most relevant major of the school that I got into. I knew I wanted to write, but I wasn’t particular about the format. There was a moment where I thought I wanted to write comic books, god forbid. Writing fiction was always in the back of my head, and I think I believed that one day I would have read enough books to be able to do it myself. Then I just woke up and was like…

ABRAMS: “Today’s the day.”

GORDON: It was like, “There will never be a moment in which I am somehow totally perfectly prepared. You just have to do it.” The moment I started to do it, everything flowed. But I had other attempts at novels. I would write tremendous chunks of something and then one day I would wake up and be like, “I don’t like the way this sounds, it doesn’t feel honest to me. I feel like I’m kind of putting on a voice. I’m trying to mimic George Saunders or Don DeLillo or whoever it is.”

ABRAMS: Many such cases.

GORDON: Then I was kind of in the midst of a professional crisis, so to speak, which is not exactly like the one that Jacob has. I was wondering what the future was going to look like. Journalism is not a stable business. I’ve known so many people who just stop doing it because the conditions are impossible. For a moment—and this still may come to pass—I was very much thinking that this could be it. When I started writing down these feelings and thoughts, I kind of had this breakthrough like, “Oh, this is the tone.” I locked in on something, which then took many different shapes and revisions and smudgings until it became See Friendship.

ABRAMS: There’s a nice parallel in that Jacob is also like, “What the fuck am I supposed to do to keep existing in media?” Was it important to you to include some commentary on what it’s like to work in this instability?

GORDON: Well, I imagine this is similar in a lot of creative fields, but almost everyone I know begins to over-identify with their job. It sounds so quaint, now that these businesses like VICE and BuzzFeed are all but done, but there was a sense when I was coming out of college that you could work for a cool place and you would meet cool people. It didn’t matter that you were only making $35,000 a year because you got to go to parties and hang out with people. Then, all of a sudden, all of these jobs stopped existing, and a lot of people realized that this job had become the basis for their identity. That’s a destabilizing thing, to come out of that into a world in which that just doesn’t exist anymore. I mean, what is a cool, digital-oriented publication that a young person of sound mind would think to themselves, “I’m putting my whole ego and identity into this”?

ABRAMS: Have you heard of Truth Social?

GORDON: Exactly. In the wake of him becoming president for the first time I and certainly a lot of people I know felt a sense of humility and shame because they thought the world could be one way and it’s really another. It’s very “millennial cringe,” as they say. But when you’re inside of something, it feels feasible. As time goes on, it feels not only implausible, but totally fucking foolish that you could have ever thought that. But then, what do you do as you go forward? What do you do when you have to find some new identity? In these moments of transitions, that failed middle class of the millennial generation was certainly on my mind. There is a character in the book who sort of realizes that the career she’s living is bullshit, and it’s not like someone who worked at a factory for 50 years that retires them. It’s people who just spent their twenties and some of their early thirties in a situation that collapsed instantaneously or almost overnight.

ABRAMS: It’s like, “I didn’t imagine I could buy a house, but at least I thought I could keep working at VICE.”

GORDON: I genuinely did not think that all these companies would just blow up.

ABRAMS: Well, your novel contends with the harsh realities of being a millennial. without falling prey to the kind of sardonic, detached voice that can be just as exhausting as blind optimism, frankly. You settle at a place in the book that is both true to these political realities, but also hopeful. What do you make of autofiction, and do you reject that label for this book?

GORDON: I would reject it, not because there’s anything wrong with it. I love autofiction. I love Karl Ove [Knausgård]. I love Sheila [Heti]. That said, I’m very genre agnostic. The classification is just not interesting to me. So while there’s unavoidable similarities to Jacob’s life and mine, the book is strongly fictional. But because there are these real world parallels, I would be a fool and a liar to claim that it wasn’t inspired by real things. I am a biracial Chicagoan who works in media and likes indie rock and has opinions about podcasts. At the same time, it is a character—a version of me who’s more of a shithead.

ABRAMS: I think that’s a beautiful place to end.