LIT

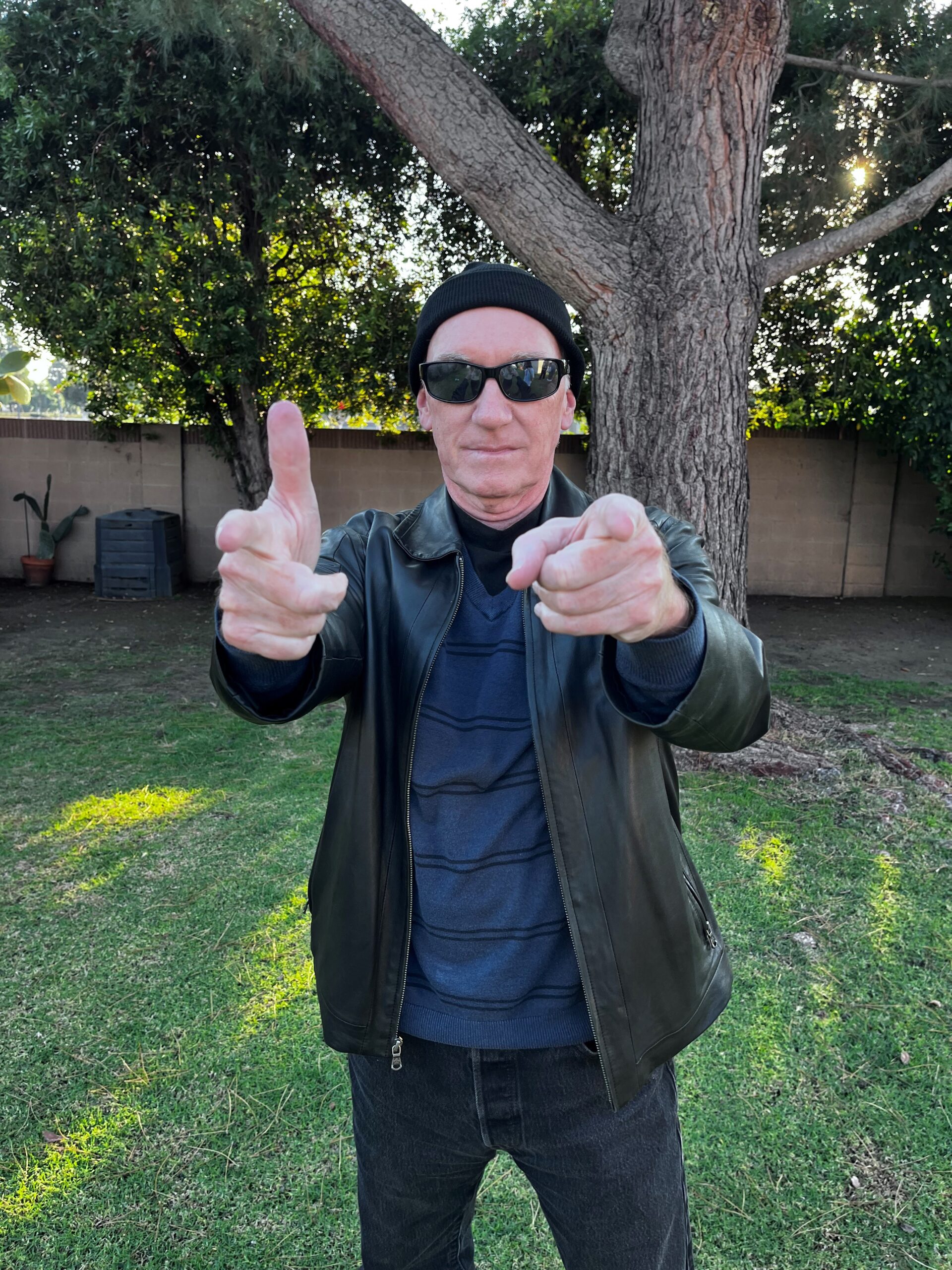

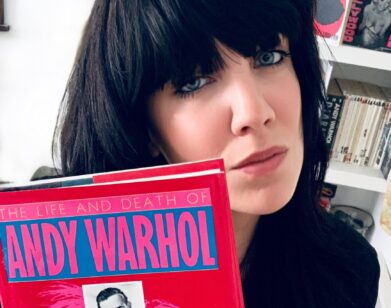

Jack Skelley on Hot Girls, Jungian Symbols, and the Naughty Algorithm

Jack Skelley’s new novel Myth Lab is horny and weird. It’s a sci-fi sexual romp that forays into both cultural criticism and hallucinatory worship of Kim Kardashian. As Whitney Mallett, the founding editor of The Whitney Review, so keenly pointed out in her conversation with Skelley below, it seems like every hot girl on both coasts has been part of the book’s rollout. Maybe that’s because Myth Lab explores a lot of the things hot girls love: elaborate nails, male fantasies, Jungian archetypes, Camille Paglia, high-low culture and, of course, romance itself. Skelley truly “loves love,” he told Mallett earlier this month. The Los Angeles native’s previous books include the cult classic The Complete Fear of Kathy Acker, which chronicles Skelley’s own adventures in the city’s counter-cultural underground, so it’s no wonder he’s amassed legions of loyal readers. Shortly after Myth Lab hit shelves, and just before the author’s wild launch party in Los Angeles, Skelley and Mallett got on Zoom to discuss Shakespeare, Love Island, his Instagram explore page, and what he describes as his “wellspring of genuine affection towards women.” —JULIETTE JEFFERS

———

WHITNEY MALLETT: What are you up to today?

JACK SKELLEY: I’m just excited and stressing about the big launch for Myth Lab on Saturday here in L.A.

MALLETT: I saw the beautiful and glamorous Mehlan [Cristalle] is your emcee.

SKELLEY: How do you know her?

MALLETT: I spent some time in L.A. during the pandemic.

SKELLEY: Oh, okay. Yes, she’s going to be our emcee. I’m really excited.

MALLETT: Every hot, bi-costal girl is a part of your book launch rollout.

SKELLEY: Is that good marketing, you think?

MALLETT: No, but I think it actually connects to the book itself. I think your writing does speak to hot girls. If I can be so bold as to say that I’m a hot girl, then you speak to our experiences.

SKELLEY: You’re definitely a hot girl. I don’t know how to explain it either, but I’m just going with it. It was not a conscious strategy.

MALLETT: I was talking with my boyfriend the other day about how there’s a lot of depth in superficial things. In your books it’s clear you love a certain type of shoe or a type of lingerie, these performative elements that people write off as superficial, but they’re really not. Maybe that’s why hot girls feel seen by them.

SKELLEY: Thank you. When you and I had our conversation at POWERHOUSE Arena for one of the New York launches of Myth Lab, I really liked how you zeroed in on a couple sections in one of the stories about nails and manicures. Because there is a deeper meaning to these superficial fashion trends, so I’m glad you picked up on that. Plus, I just think they’re hot. Nails are hot.

MALLETT: Yeah.

SKELLEY: And shoes.

MALLETT: Yeah. Shoes, nails…

SKELLEY: And Fear of Kathy Acker did explore that a little bit. I think there is a connection between Fear of Kathy Acker and this new book in terms of the fetishization of commodity culture.

MALLETT: Yeah.

SKELLEY: [There’s a] sort of self-mocking approach towards it, but also, it’s celebratory.

MALLETT: You always have a bit of that self-mocking, but at the same time, you make a stew with a lot of serious stuff. It doesn’t take itself too seriously, but it’s not also unserious either. There’s a flickering between that, and it gives it a velocity. Your writing is a pleasure to read.

SKELLEY: Oh my gosh, that is so nice to hear.

MALLETT: I’m being too nice.

SKELLEY: You’re very much too nice. I think this sexual fetishization and fetishization of commodity culture and trends is a subset of a larger fetish that I have for pop culture. Pop culture is tenuous, but I’m also interested in a real connection to high culture or deep culture, and trying to capture the arc. I use the term archetypical, as opposed to archetypal, because there are archetypes in our subconscious and in our world of symbols that we live in. Our entire language is symbols. These archetypes can filter down into our everyday experience, even on the most mundane, superficial level in terms of advertising, pop culture, TV, movies, pop stars, et cetera.

MALLETT: Yeah. There’s depressing aspects of “trashy culture.” Like all the Reagan stuff in The Complete Fear of Kathy Acker, the sickness of the society we live in.

SKELLEY: Yeah.

MALLETT: It’s like, why be a serious person in this world? Politics is stupider than Love Island. Do you watch Love Island?

SKELLEY: No, but I’ve been wanting to. I feel like I would like it.

MALLETT: I think so, too. But I guess the point is, it’s trash. It’s like the Democratic Party… It’s so vacant.

SKELLEY: You know, there’s a great Elvis Costello line from one of his very first songs, “I used to be disgusted. Now, I try to be amused.” Whatever character arc I went through a long time ago, it was a reaction against my own reaction, my own political and/or cultural annoyance with what is really a sick society. Perhaps, people like you and me, we have some kind of consciousness of how we are a product of society and language and all these symbols. We can be aware of that, while still critiquing it.

MALLETT: Yeah, having some self-reflexivity. Can I ask you a personal question?

SKELLEY: Sure.

MALLETT: How old are you?

SKELLEY: A lady never tells. Let’s just say I’m a late-blooming boomer.

MALLETT: You’re old enough to be my father.

SKELLEY: Yes, I am.

MALLETT: Not to be so gossipy and bottom of the barrel, but I am kind of curious. You’re hanging out with all the girl writers. We talked about how with Myth Lab, there’s this tease, we don’t know if it’s your life or not your life. I do wonder if you engage in age gap relationships.

SKELLEY: Oh my gosh, you are really getting into it here.

MALLETT: I mean, I have to ask. You don’t have to answer.

SKELLEY: I can’t get too specific about that. And we covered this in our last conversation, when we were talking about autofiction, right? I think you and I share an impatience with that term, but also an understanding that when it’s done in a fun or effective way, autofiction can inspire questions like the one you just asked.

MALLETT: Yeah.

SKELLEY: Readers really want to know, “Did that really happen?”

MALLETT: Exactly. And I say it because I feel like I just have to get it out of the way. It’s a question that one cannot help but wonder when you read, you know?

SKELLEY: I can’t help but not answer it. You know what I mean?

MALLETT: That’s your prerogative. But I also wanted to just bring it up to almost deflect the criticism before it’s there. Because it could sound cringe, an old guy writing about cuties and pleasure dom, but it isn’t. You’re not writing about dick and pussy and being horny for no reason. There is a generative quality.

SKELLEY: Hopefully it’s not too creepy. And it springs from another thing that more or less happened unconsciously in Fear of Kathy Acker, which is to write from this wellspring of genuine affection towards women. And a love of women’s writing, especially. Some of the stories in Myth Lab create preposterous theories about women inventing time and space travel. There’s a chapter called “Rendezvous with God-MILF,” which has a lot of sub-chapters about transgenderism and the exploding of sexual types and tropes. Again, it all springs from a genuine love and interest in care and happiness.

MALLETT: I mean, you love love.

SKELLEY: Oh my gosh, that reminds me of an epigraph from Julia Kristeva: “Souls that love see all the way into atoms.”

MALLETT: Let’s talk about craft for a minute. Your writing is so loose, but I also know that it must be very worked over. It’s not an accident, so how do you do it?

SKELLEY: Thank you. I like that question, too. Just recently, I did an interview with Dennis Cooper in Write or Die Magazine where we got into sentence structure and our exacting approach towards prose. Both Dennis and I are really into working over sentences, swapping out synonyms, balancing short clauses with long, long passages. Finding a balance between musicality and content within the prose, to the point where, ideally, it even approaches poetry. I guess the standard trope of prose versus verse is that, in prose, the language is transparent. The reader sees through the language into the meaning. Whereas in poetry, the effect is very much on the surface with wordplay and sounds and alliteration and rhyming. So, it is a thing I really love to play with.

MALLETT: Do you write every day?

SKELLEY: Pretty much.

MALLETT: Are you a morning pages kind of person?

SKELLEY: Totally. I get up very early, by 5:00 or 6:00, and there’s that special hour before the rest of the house wakes up and I can put on some ambient music and just zone in. How about you?

MALLETT: I’m a writing on deadline person.

SKELLEY: Yeah. I love your critical writing and your nonfiction, but do you also write fiction or verse?

MALLETT: A little bit. I like readings because they give me a deadline to write something more experimental. I wrote this really short thing for the Paris Review, which was supposed to be a review of a porn, but I basically just described surfaces of the McMansion it was filmed in. And I just did something similar about the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader reality TV show.

SKELLEY: I’m writing that down.

MALLETT: People want something jagged or spiky. You want to be startled. When you read a sentence, you want there to be a little bit of surprise. But it needs to have tension. It has to have some smoothness. You have the crunchy and the smooth at the same time.

SKELLEY: I like “spiky.”

MALLETT: I wrote some words you’ve used: “Crummy” and “sleazy” and “scummy.”

SKELLEY: Crummy, sleazy and what?

MALLETT: Scummy.

SKELLEY: You know, I do use “crummy” a lot in my regular discourse. Camille Paglia gave a talk on Hamlet. Hamlet has just killed Polonius and says, “I’ll lug the guts into the neighbor room”.

MALLETT: “Lug guts.” I guess you got it from Shakespeare.

SKELLEY: Everything comes from Shakespeare.

MALLETT: I also have to say that I kind of hate L.A., but I think it has great narrative potential. I love books and movies set in L.A., but…

SKELLEY: What do you hate about L.A.?

MALLETT: I don’t want to live there, but I want to read about it.

SKELLEY: Have you spent much time in LA?

MALLETT: During the pandemic.

SKELLEY: Oh, that’s right.

MALLETT: I was dating someone who was kind of like a little bitch, which might have soured my impression of it. I was staying in the Flower District, kind of like Skid Row adjacent.

SKELLEY: Oh, downtown. I know that area.

MALLETT: There’s some passages in Fear of Kathy Acker that described like, the hemorrhoids of the warehouse district. It is really fascinating to walk around down there. It gets so dead and it’s very lonely.

SKELLEY: “The downtown warehouse district is the hemorrhoidal periphery of the downtown shopping district, which is the butthole of the city.” That’s from Fear of Kathy Acker. I think you probably were spending a lot of time in Koreatown. They have these crazy names for stores. In fact, going way back to my ancient pedigree as a literary person in the olden times of L.A., I had a band with Bob Flanagan. And the name of that band was Planet of Toys. And Planet of Toys was the name of a toy store in the Toy District. That’s where I got the name for a poem that became the name of the band, too.

MALLETT: Was the music scene and the alt-lit scene more connected than it is now? I saw a Sonic Youth flyer and then it said, “Reading by Jack Skelley.” I feel like that’s different, the bands and the poets being one interconnected scene.

SKELLEY: I think that particular gig was a gig in a punk club. My band, Lawndale, played with Sonic Youth. We ended up being on the same label together. Whoever set up that gig knew that I was in a band, so I was asked to perform a literary thing as well as perform with my band. Maybe it was a little unusual, and I still try to do that today.

MALLETT: What is your Instagram explore page like?

SKELLEY: Oh my god. Is that the one where you…

MALLETT: Yeah, it suggests things they think you’d like to watch.

SKELLEY: I’m really ashamed of it. Obviously, they know your algorithm too well, and it’s a freaking naughty page.

MALLETT: I wondered if you follow foot accounts.

SKELLEY: No, I’m not really into feet that much.

MALLETT: You’re more into shoes than feet.

SKELLEY: Yeah. And nails, for sure.

MALLETT: Yeah. Well, I feel like I’ve asked you a lot of personal questions. Is there anything you want to ask me?

SKELLEY: I mean, what the heck? Tell me what brought you to this place where you’ve got The Whitney Review. The Whitney Review is this rainbow-type confetti of amazing voices and literary interactions. Can you give us the shorthand bio of how that happens?

MALLETT: I worked with so many writers at different magazines. But that’s not a good answer. I know a lot of people, and I knew a lot of people would have a book they wanted to write about. There’s not enough places to write about books, or they have to be interviews, or they have to be [written] by a person that has a certain kind of persona to be in a general culture magazine. I always said I would never start a magazine because it’s so much work, but here I am.

SKELLEY: How do you network? It seems like you network quite a bit.

MALLETT: I went out like, five or six nights a week for 10 years.

SKELLEY: Right.

MALLETT: If anything, I go out a lot less than I used to. But I’m compulsive. I would go to everything. Now, there seems to be this more interesting resurgence of alt-lit, but I was going out a bunch. Everything I went to was music, performance art. It has an interdisciplinary spirit. There’s great writing in some of these publications, but I feel like there’s a stereotype that’s kind of true about some of these lit magazines where everyone went to Harvard and only socializes with other writers. They have a lot of blinders on about what else is going on.

SKELLEY: It feels to me like there is a pretty hard divide between alt-lit and underground lit and more academic or large press lit. Is that fair to say?

MALLETT: Maybe socially or business-wise, but I think that these things are in interaction with each other. There’s this wave of writers getting picked up by bigger presses that come from this energy. Everyone has to market themselves. Even when you’re on a big press, they’re like, “Oh, we’ll sign you because you already have an Instagram following.” More and more should be done to put things in conversation, because the influences are always ping-ponging back and forth.

SKELLEY: I’ve just found I don’t have enough of that. I’ve done readings where I’m definitely in the smaller camp, the indie lit world. But I’ve done events or readings where there was another person who had a big novel and had “made it”, so to speak. I’m feeling a little ghettoized or something like that, and I don’t know why. I wish it was more like how you described.

MALLETT: Yeah, it’s interesting. I’m writing for Document Journal right now about Semiotext(e). Every Semiotext(e) author has a very different trajectory. Some will do a book with Semiotext(e) and then a book on a bigger press. There’s no rule or real trajectory.

SKELLEY: Right. I think Semiotext(e) occupies a very valuable demilitarized zone between those two worlds. It’s definitely a smaller press, but it has an avid following and its able to get its books into wide circulation. The distribution is very good, and the quality of the authors is tremendous. There’s an automatic cachet that comes with them.

MALLETT: I mean, they say that Colleen Hoover is the only one who makes any money.

SKELLEY: See, I don’t even know who that is. Who’s that?

MALLETT: It’s like, really bad writing. They’re romance novels for millennial girls that are like, “I want him to open the door for me, but I don’t.” But, she also self-published for a while. It’s depressing when you’re like, “Oh, that’s what the masses want to read.” But maybe the masses are smarter than people give them credit for.

SKELLEY: Correct. And it’s even more depressing when you realize that the authors that “make it” are so few and far between. I think even the successful “novelists” still have to struggle quite a bit.

MALLETT: Most still have their jobs, teaching or working in advertising or whatever it is. Did you ever do genre?

SKELLEY: No, I don’t do genre. People have said that this Myth Lab has science fiction in it, which it kind of does, but not…

MALLETT: Not in a plot way.

SKELLEY: No. And it’s not narrative at all.

MALLETT: Well, maybe you have to try to get them to make Myth Lab the movie, then you can sell out and make the big bucks.

SKELLEY: I would like to. I wrote this book that came out three or four years ago about the Manson family and the dead Beach Boy, Dennis Wilson, and it did get optioned for a TV show. My fingers are still crossed.