LIT

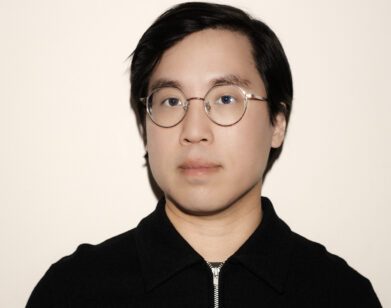

“It’s a Bit of a Puzzle”: Justin Torres on His Sophomore Novel, Blackouts

Eleven years ago, Justin Torres published his debut novel We the Animals. For those of us who fell in love with Torres’s tough-edged lyrical prose, it’s been a long wait for Blackouts, his second novel, which has all the precocious energy of his first book, but also the clarity and wisdom of someone who’s spent a serious bit of time reflecting on the intricacies and histories of the known and unknown queer world. You could think of Blackouts, which has been shortlisted for the National Book Award, as a folio, or a scrapbook of personal reflections, painful histories, an album of photographs and illustrations, love stories, sex stories, loss stories, and redacted case testimonies from a real-life early study on homosexuality called, Sexual Variants: A Study in Homosexual Patterns. That all makes Torres’s accomplishment sound artful and experimental, which it is, but Blackouts soars because it’s a profoundly moving story about a young gay man, our narrator, who travels across a desert to spend time with an old gay man named Juan on his deathbed. It’s these two characters, the intimacy of their voices, and their willingness to hear each other out, that makes Blackouts a rare masterpiece. But as you can tell, I’m a fan. I spoke with him at the end of September and didn’t expect to find him in a parking garage.

———

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: Where are you?

JUSTIN TORRES: I’m in a parking garage. I had to take my friend to the doctor all of a sudden, but everything is going to be fine. Is this quiet enough?

BOLLEN: Yeah, I can hear you fine. But the way you’re lingering in the parking garage might look ominous to people walking to their cars. But it’s a hospital parking lot, so who would be that cruel? Anyway, congratulations. Finished the novel last week and haven’t stopped thinking about it. I usually don’t like to ask writers about the mechanics of writing, but I feel Blackouts a special case because of the sheer number of different ingredients that you manage to snap together—visual images, dueling narratives, redacted case studies, movie-script briefs, flashbacks, personal and public histories, basically a bag of jigsaw pieces that you can’t imagine making one cohesive picture.

TORRES: Yes, there’s so much that went into it. First, there’s the Sex Variants book that I always wanted to write about.

BOLLEN: How did you first come across that book?

TORRES: I was working in a bookstore, and somebody brought in a box of books. And it was kind of clear that whoever owned the books was queer and dead. It just had that vibe. Like it had Jean Genet and The Well of Loneliness and a lot of literary stuff that I knew. And then this random study. I was so taken by the voices in it. I knew I wanted to write about that, and I had been carrying it around that with me for years. I tinkered in various ways, and started to think about Jan Gay [a gay researcher whose work was coopted by the study] and her history. And I’d also been writing these stories about a sex worker, and I kind of lost this manuscript. I called them my whore stories.

BOLLEN: How did you lose them?

TORRES: I was in a train. And I left it in the backseat. On my laptop. I left my laptop in the backseat of the train. It was before the Cloud, or at least before I knew about it.

BOLLEN: It’s like a modern Hemingway crisis. His wife left the manuscript for his first book on a train. Their relationship never recovered.

TORRES: The few stories I had left I’d either published, or had emailed to somebody, or something. So there are these residual bits that become the backstory of the narrator who’s making his journey to visit Juan in Blackouts. But it took me a long time to realize how I wanted to pull these pieces together and how they were speaking to each other. I also started rereading a lot of books, like Kiss of the Spider Woman. I reread it just on a whim, and I was like, “Oh, holy shit. Two people in a room talking to each other.” Two people from very different life experiences telling their narratives. I mean, in the case of Molina [the gay hairdresser who shares the prison cell in Kiss of the Spiderwoman] telling his narratives in the form of films. It was like, that was the missing thing, because I had the two people in the room. I thought, “I’m going to pay homage to [Manuel] Puig and marry these film plots.” It felt like the final piece of the puzzle.

BOLLEN: A topic very dear to my heart is the relationship between gay men of different generations, and the sharing of experiences between people of radically different ages. And in Blackouts, between the narrator and Juan, you tackle it so beautifully, with this young man coming to spend time with this dying, old man.

TORRES: I think what happened was that for my first book, I was very much borrowing things from my own life, even though it’s fiction. And it’s about this one family. It’s a very claustrophobic book in a sense. And I wanted to become a different kind of writer. One of the things that I did was, I just started rereading things I hadn’t read in a long time. I was kind of rereading the queer canon. So I felt like I was in dialogue with these other generations, a literary dialogue. And personally, I wanted to kind of get outside of myself a little bit and get more of the world in there. As far as the narrator and the book is concerned, I think it’s very much the same thing where Juan is trying to get him out of his own self-importance and pessimistic narcissism. He’s in his 20s. He’s kind of lost. He’s wandering through his life. And Juan is saying, there’s a whole lineage, and heritage, and so much out there, so much history that you should want to know about. I’ve had those experiences in my own life where mentors, where you’re just like, “Tell me about the queer world.”

BOLLEN: Me too. Absolutely. It’s an education you can’t get anywhere else, and you don’t get it growing up, so you’re thirsty for it when you find someone who can speak to it. One of the things I thought was perfect about Juan was his wit and humor. This is a melancholic, mournful book in many ways, but there are moments in their banter where the humor comes through.

TORRES: I’m 43, about to be 44. The generation right above me is kind of a lost generation, wiped out by the pandemic, but not entirely wiped out, right? There are a lot of people from that generation that I’m friends with. And then, the generation above that is leaving the Earth all the time right now. But one thing that works as a through line down to my generation, is this idea that you laugh at yourself. It’s something in the queer sensibility, something about camp, a part of the lesson: Don’t take it too seriously. The world’s going to give you fucking shit. You’ve got to be able to laugh at yourself. I teach as well, and I’m really enamored with this new generation. I think that they’re doing a lot of interesting political work. They’re really dedicated to changing the world. But I sometimes worry about—

BOLLEN: Their self-seriousness.

TORRES: Yeah. The seriousness of it all. There’s something about just wit and humor. That’s the legacy.

BOLLEN: The older I get, the more I have no patience for the humorless. You want the humorless to help you in an emergency or when you’re at the DMV. But otherwise…

TORRES: It’s how you learn, right? When someone says something so cutting and funny, you pay attention, you’re asking yourself why it’s funny.

BOLLEN: When you were working on this book and battling all of the competing elements, did you have a lot of support? Or was there a chorus of, “Justin, can’t you just write We the Animals Part 2?”

TORRES: Everybody thought that I was crazy. There were definitely a few people who were like, “You wrote a book that people liked and want more of that.” My agent, I didn’t show her a lot until it was kind of done, said, “Don’t take this the wrong way. It’s not an insult, but it seems like it wasn’t written by an American.” And I thought that was the highest compliment.

BOLLEN: I see what she means. It has such an unconventional structure and it doesn’t conform to American storytelling arcs. Like Sebald style.

TORRES: You said a puzzle. It’s a bit of a puzzle. It’s a little bit challenging. And you’ve got to slow down a little bit. It felt risky. But I couldn’t write a sequel to We the Animals. As much as this book is very much aligned with that, and you could even say the narrators are similar personas. But for my own personal development, as somebody who’s interested in literature, I’d rather fail.

BOLLEN: I remember when your first novel came out in 2012, and then following book announcements over the years expecting a follow-up from you. It’s eleven years. Did you feel a pressure to come out with someone that equaled the success of the first? I’m not accusing you of playing video games for the past eleven years.

TORRES: I was getting a job and becoming a professor. And also, things were so precarious before We the Animals. My whole life had just been precarity. And then suddenly to have stability. I was kind of catching up with myself. I also I felt like I was thrust into the world and people. Literally, the book comes out, and people are like, “Tell us your thoughts on contemporary Latinx literature.” I always feel like I was thrust into the world to be a public figure in a way that I wasn’t. I was very aware of the gaps in my own knowledge and education. It takes time.

BOLLEN: You live in L.A. Is that where you wrote most of this book?

TORRES: A lot in L.A. and a lot in Oxford because my boyfriend was living in Oxford until very recently. I spent all of Covid in Oxford, and that’s really where I finished the book.

BOLLEN: Did the National Book Award longlist surprise you?

TORRES: I was shocked.

BOLLEN: A little part of you wasn’t like, “exactly”?

TORRES: No. I wasn’t expecting at all. I think all you ever see is the gigantic space between what you’re trying to achieve and what you’re actually capable of. As it went out to the world, I was trying to pull it back. I was calling my editor being like, “I can’t. It’s not there.” I wanted to pull it.

BOLLEN: You felt like you had more to add?

TORRES: Yeah. I don’t know. One day I would read it and I would be like, “Okay, it’s done.” And then, the next day I would read it, and be like, “Oh, my God. It doesn’t work at all.”

BOLLEN: I love the title. Was the idea of “Blackouts” an early or late piece of the puzzle?

TORRES: Pretty early on. It helped me, because when I realized I didn’t want to write an historical fiction and bring to life all of these anonymous participants in the study, I was like, “Well, what do I want to do?” And that’s when I started blacking out this text, just kind of playing. When I did that, I started thinking about the idea of erasure and blacking out. And the idea that it sometimes can be a protective act. I also have a terrible memory, and sometimes there are black spots because you’re overwhelmed. It helped as an organizing principle in the book.

BOLLEN: I don’t want to keep you. I’m worried your friends need you in the hospital.

TORRES: Don’t worry. I’m here. They’ll be fine.