REAPPRAISAL

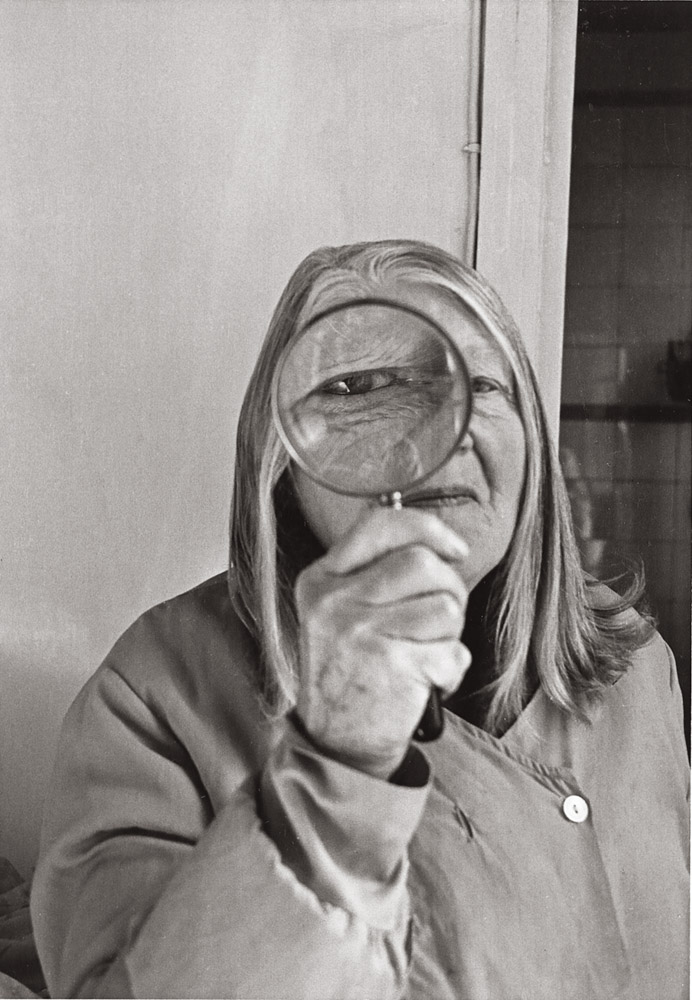

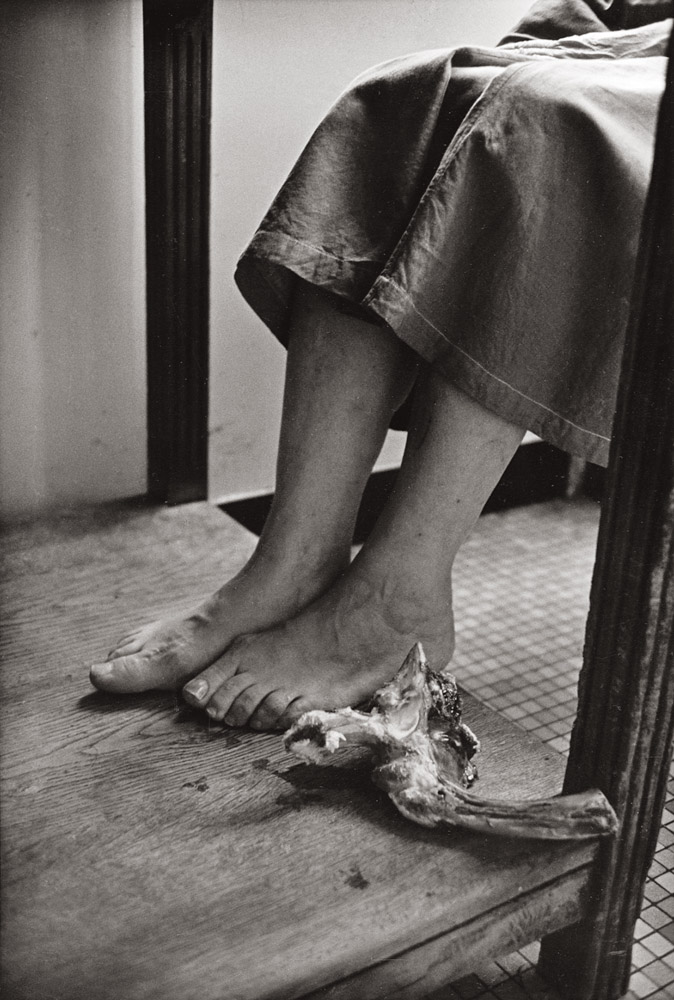

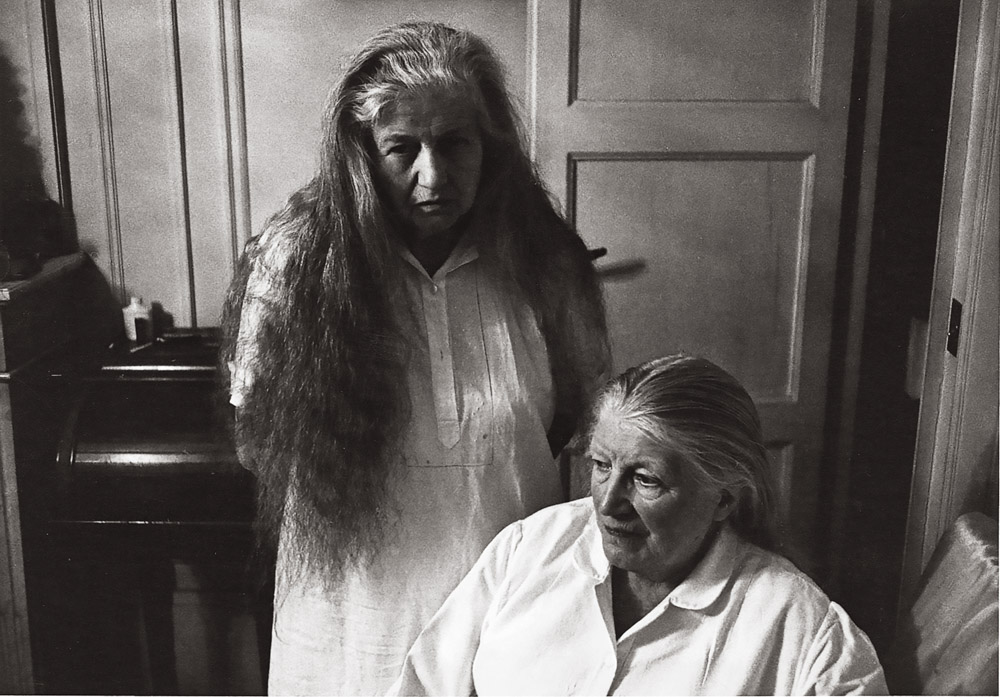

“It’s Intimate, But Also Perverse”: Inside Suzanne and Louise, Hervé Guibert’s Lost Photo Novel

By the time I was introduced to Hervé Guibert, he had already been dead for 24 years. Gracing this planet with incessant wrath from 1955 to 1991, the French writer, photographer, and filmmaker pioneered autofiction and then passed away in unsheathed honesty, documenting his dying days with AIDS. But since 2014, Guibert has gone through a process of resurrection.

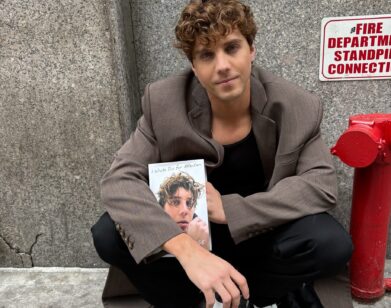

The only way I can explain the mixture of admiration and jealousy I feel when reading Guibert is by disclosing my own grandiose secret: I believe parts of him—during that inevitable scattering of psycho-matter called death—got mixed up in my mother’s womb. For years, I’ve searched for anyone this fixated on Guibert, though none left me with the impression that they too would sell off their unborn child in exchange for just one night with him. Then, I met my match in Jordan Weitzman.

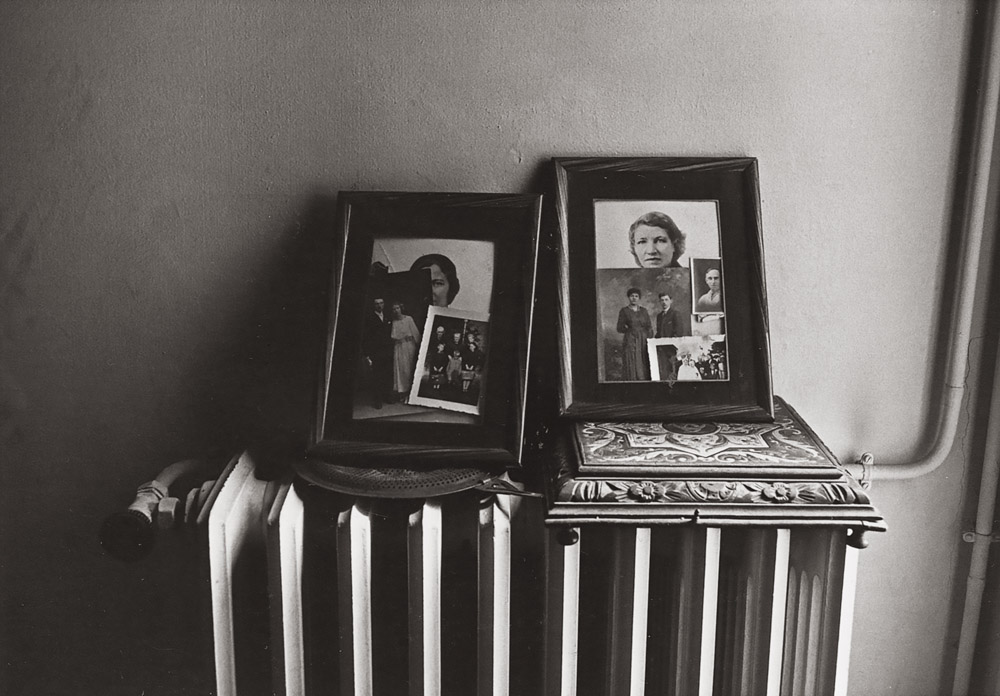

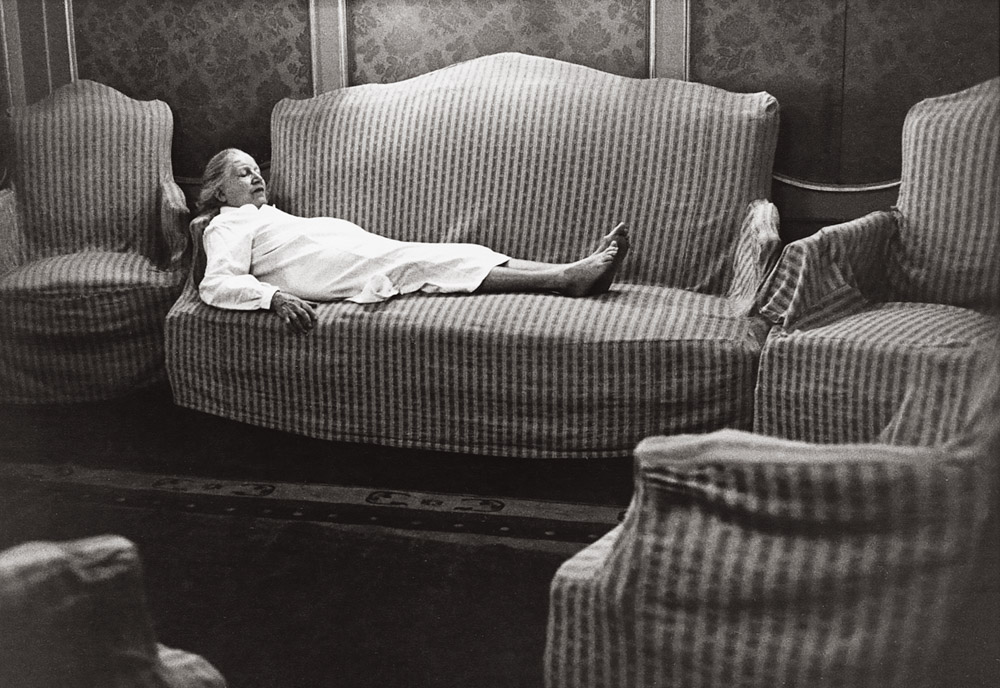

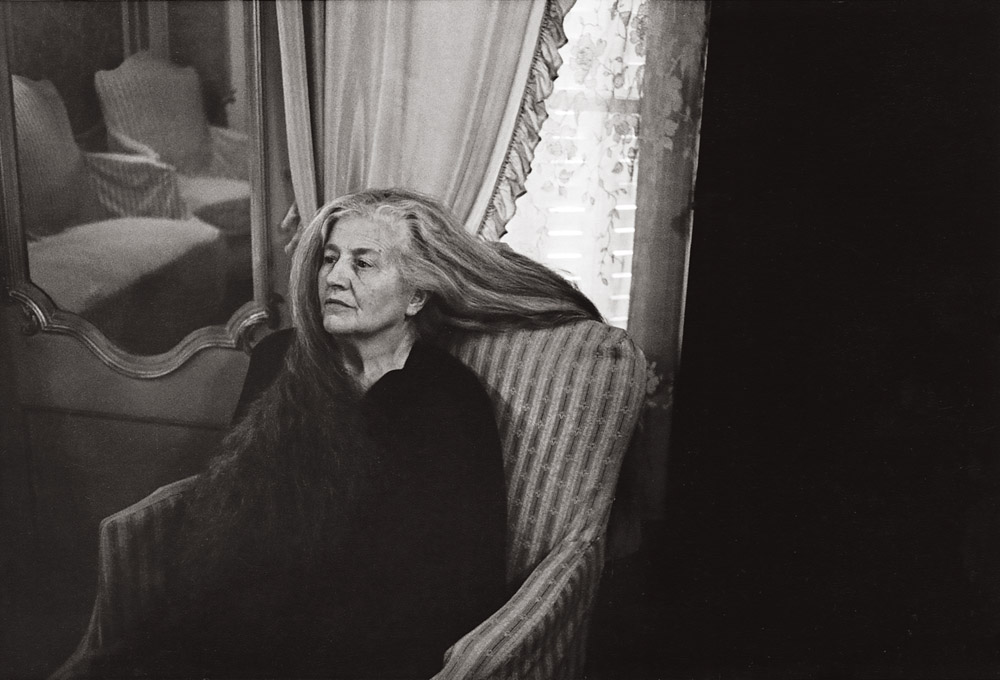

In 2016, he founded Magic Hour as a platform for discourse on contemporary photography that eventually became a small press publishing books on Corita Kent, Peter Hujar, and Ian Lewandowski. Its sixth publication is the English translation of Guibert’s 1980 photo-novel Suzanne and Louise, a destabilizing and merciful view into the relationship with his two reclusive aunts, who lived hermit-like in a Parisian hôtel particulier, seemingly only interacting with the outside world through their nephew. Earlier this fall, ahead of the book’s reissue, I joined Weitzman in his kitchen in the Lower East Side to discuss his hopes as Suzanne and Louise joins the Guibert English-oeuvre and the uncertainty of intuiting wishes of someone far gone.

———

JACKSUN BEIN: Okay, we’re rolling. What initially brought you to doing a project on Guibert’s work?

WEITZMAN: I came to this through Moyra Davey. She introduced me to the book and she said, “I know someone who’s been working on an English translation of it, you guys should meet.” So I met Philo Cohen who had conceived of this project, and I was totally into it. I had already gotten really into Guibert, so she put me in touch with Gallimard, the big French publisher who originally published the book, and I ended up negotiating the rights to do an English translation. It was a bit of a drawn-out negotiation, but once we actually got it done, I was super excited to work on it.

BEIN: Do you read French?

WEITZMAN: I read French, yeah.

BEIN: So was the first copy that you read the French version or was it the translation?

WEITZMAN: I’m bilingual, but Guibert writes in a difficult French. It’s not so easy to understand. Even sometimes with French movies, if I have the option to read subtitles in English, I’ll default to my mother tongue. So at first I read the French and then I read the English.

BEIN: What do you mean that his French is difficult?

WEITZMAN: He writes in a particular way. There’s a baroqueness to his writing that’s sometimes a bit difficult. Even when you read the translation with the flow of his sentences and his use of language, sometimes you have to go back and reread a sentence or something. It’s just a bit dense.

BEIN: Yeah. Well, I think something I have always been really drawn to in his writing is that he utilizes past and present and future tense in a really strange way where he starts to make you go into these loop cycles. For example, the moment where he’s talking about putting down the dog, you expect to turn the page and see the image, but actually before you even get to the point of turning the page, he says that the image never was taken because she hadn’t contacted him. There’s this repetition of a phrase that he does that changes whether it happened or didn’t happen, which is something that he’s played with in a lot of his work.

WEITZMAN: For sure.

BEIN: You mentioned that you had already been really interested in other writings of his before this. What was drawing you to the previous stuff?

WEITZMAN: It was a combination of a bunch of different things. I think it had to do with reading some of his writing, seeing his photos, learning about him as a person, and also seeing pictures of him. it was almost like falling in love with him in a way. I’ve often felt like that in the past year. You can fall in love with someone through their work, and it became something that just kept on building and building. I say that because it’s like this feeling where there’s someone that you want to keep on going back to, you want to know more about, and that doesn’t stop. You know? You keep on wanting to return to this person.

BEIN: Yeah.

WEITZMAN: And it continues to unfold because he died of AIDS at 36 years old in 1991, but he had been super prolific in his life. He published 25 books. He was a photographer. I mean, he called himself an amateur, but he was really serious about photography. He was the photo critic for Le Monde in Paris, so he was a journalist and an interviewer. He just did a lot. It’s like you just keep on discovering things.

BEIN: Were there moments of working on this book that unsurfaced parts of him as an artist or as a person that you hadn’t seen before?

WEITZMAN: For sure. First of all, he’s really young when he publishes Suzanne and Louise. When the book was published, I think he was 25. He had been working on this, and at first, it was a play, then he wanted it to be a movie. Finally it finds this form as a book. So even thinking of this dynamic of this young guy who is really interested in these two older women and visits them, photographs them, writes about them, there’s just something really interesting in that. And then there’s this experiment of the photo novel. Moyra says this in her intro, and she’s totally right, that this is the only example of a book of his where his talents as a writer and as a photographer combined. So it’s really unique.

BEIN: Yeah.

WEITZMAN: There’s also a really sophisticated quality to it, especially for someone who’s so young. It’s intimate, but also perverse. It’s about them, but it’s also about portraiture and photography and performance. There’s the section about the dog and where he asks one of the aunts to put on the dog’s muzzle, which he then photographs her in. You can look at it as a metaphor for performing in front of the camera and the different power dynamics between a photographer and a subject. So there’s a lot in there.

BEIN: Right. And as the only photo novel he did, the images aren’t supplementary and the text isn’t supplementary. They really do somehow bleed into each other in this way that I don’t think I’ve ever really seen before. He’s not overzealous in either of them. Both of them are restrained in a way that I think makes the whole thing so perverse because you’re also wondering what letters may have been sent or what things were happening before the images that we’re seeing. I mean, I think the thing that is shocking to me about how young he was is how he was so persistent in all of these other experiments before the novel itself, returning again and again to them. It’s really shocking that there had already been such a deep investment that is so sprawling. You probably know a lot more about their relationship before the book.

WEITZMAN: Well, this is one of the first books that he publishes. And talking about that investment, he returns to them over and over. One of the last books that he wrote before he passed away, in the late ’80s, was called The Gangsters, which stars them. And then the last film before he dies, La Pudeur ou l’impudeur. Have you seen it yet?

BEIN: I haven’t. I want to see it so bad.

WEITZMAN: I have a copy. I’ll send it to you. I mean, it’s a pretty remarkable film because it’s the last thing that he makes. He’s literally on his deathbed, dying of AIDS, and he has the energy and the desire to make something else, let alone a film. And it’s crazy. They’re by each other’s side and they’re talking about death in this very matter of fact kind of way. He’s asking them how they feel about suicide and him killing himself. They’re also dying. So it’s this extremely intense, crazy thing.

BEIN: Yeah.

WEITZMAN: It’s so multilayered. I mean, he loved these two great aunts of his and they were really important to him. He finds his voice pretty young. He finds the thing that he keeps on exploring in his writing and his photos very, very early on. All of his work is what would become to be known as autofiction, so Hervé’s the main character and his friends, usually in initials, are the other characters in the book. And his photography is all about the people in his life that he loves and cares about. So Suzanne and Louise is an example of that. It’s one of two books of photos that he did in his life, and next year, I’m actually going to be publishing the other photo book, which is called Le Seul Visage, “The Only Face” in English, and it’s an exhibition catalog of a show that he had in 1984 at this gallery called Agathe Gaillard in Paris. It’s the book that I’ve returned to the most in the past year. It’s a really thin book made up of double-page spreads, but it’s just edited and sequenced in such a brilliant way. It also has a piece of text, which is being translated, which is almost like a treatise on photography. I feel that it’s really ahead of its time.

BEIN: The book also starts out with this passage where he talks about photography being unable to really do something on its own, and that the thing that makes a photograph a “good photograph” is something like “the order of love or of the soul forces that pass through and inscribe themselves fatally”. So there’s a sense already that what he’s doing is in relation to photography and not just the great aunts. Do you feel like the way that he writes in this treatise on photography is in correspondence with this?

WEITZMAN: Totally. His ideas are very confident. He makes the argument for photographing based on love or desire, and the people who matter to you. Now, it doesn’t seem as wild of an idea because a lot of people work in that vein, but if you think about the context of when he says that, this predates Nan Goldin and The Ballad of Sexual Dependency in its book form and that whole movement in photography which she really established.

BEIN: Yeah. And reading it, the first thing I thought about was that it’s the first work of his that I’ve read that is just so incredibly tender. He’s so full of admiration and love and desire, and that supplies this counter to the vulgar transgressive tendency of a lot of his other work. I feel like in the past couple years people have been reprinting more of the more transgressive work of his.

WEITZMAN: But this is why I think he’s so interesting, the range.

BEIN: I’m also wondering how the experience of working on the book was after already having fallen in love with him. I feel like a lot of times when people are resurfacing work by artists, it’s the process of resurfacing that makes you fall in love with the person, but you said that it was before.

WEITZMAN: I think so. I mean, it was just a big honor. I felt really proud of it and wanted to do it justice. I’m happy to make this thing accessible to different people.

WEITZMAN: I’ve done a couple books with artists who are not with us anymore and you feel like you’re in dialogue with them a little bit. Another thing with Guibert, you’re never sure whether he’s telling the truth or if it’s fantasy. I have to find this exact quote, but I loved hearing Mathieu Lindon tell this story. Mathieu Lindon was one of his good friends and the son of the great French publisher, Jérôme Lindon, who ran Les Éditions Minuit, who was also Hervé’s publisher.

BEIN: Wow, okay.

WEITZMAN: Mathieu was also one of Foucault’s young, cute intelligentsia. But he said that Hervé told this story and he tells Foucault about it like, “I was there. This didn’t happen at all.” And Foucault says something like, “Yeah, leave it to Hervé for false things to always be happening to him.” It was much more eloquently put, but he totally felt a freedom to just play with his life, to write whatever he wanted. And he even touches upon that in the book. At one point, I think one of them says, “What you’re writing is too close to home.” And all photos look real, because photos are in fact of real things, which makes the believability of his writing that much more potent.

BEIN: Yeah. Even with the letter, at that point, another sister comes into play. And you’re like, “Wait, where was this other sister the whole time?” Or “Is she in one of these pictures because they were twins?” There is an incessant uncertainty around who is who and what happens. Maybe that has something to do with why people are getting so interested in him again. Because he had so much success during his lifetime and then it was quiet after he passed away.

WEITZMAN: I mean, he was successful, but in this small Parisian intelligentsia. He only really became more famous, and this mainly in France at that time,, with To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, which is about his and Foucault’s experience living with AIDS and Foucault dying of AIDS. That made him the spokesperson for the subject. In Paris, all of a sudden, he starts to appear on talk shows and he’s on posters around the city. But it’s hard to know how well-known he was outside the literary or photo world.

BEIN: Right.

WEITZMAN: Edmund White wrote this amazing piece on Guibert. I think they reprinted it in To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life. He knew Guibert, he lived in Paris, and he said something like, “In France, there’s this culture where you could put out a book every year and it’s not a big deal.” It’s not like in the States with these big celebrations and events when books come out. And White argues that maybe writers could be a bit more experimental because of that. You could just write something and put it out into the world.

BEIN: This is a question that I am continuously coming back to, but his work has been translated and printed in America since 2014. Why do you think that’s happening now?

WEITZMAN: I don’t know. The Mausoleum of Lovers was put out in 2014 by NIghtboat. Do you have a copy of that, by the way?

BEIN: I do. I love that book.

WEITZMAN: Me, too. It’s so good. And then Semiotext(e) has put out a bunch of them. I think it’s been almost like this trickle of things getting put out that add to the whole narrative. Suzanne and Louise is coming up this fall, and then next year, The Only Face. And I also got the rights to The Gangsters, which I was just talking about. And there’s even something else that I don’t even want to mention yet, but for me as a publisher, the impulse is just excitement.

BEIN: Well, you’re in love with him, so you have to.

WEITZMAN: Yeah. I wonder what else it is that’s contributed to his resurgence.

BEIN: Well, this isn’t the first time that you’re working as a publisher with the work of somebody who’s passed away. What is that experience like? I assume you have to make a lot of decisions without the person and place yourself inside of them to an extent.

WEITZMAN: I think you feel a certain responsibility to do the thing justice. For them and for you as a publisher. I think a lot about books in general and how they look and feel, and you’re always in dialogue with the work itself, so you want the design and everything to reflect the work. There’s just a lot of care that goes into it. The Sister Corita book had a very similar feeling, or the Peter Hujar book. You’re also working with estates. So in this case, Christine Guibert has been running the estate since he passed away. She inherited it. And Gallimard, the publisher.

BEIN: It’s like getting to hold the person. That also feels like the piece about having been in love with them, is just getting to hold them.

WEITZMAN: Yeah. Here’s an interesting story. There’s this photo over here by Duane Michals that was the last piece of the book that came together. Duane told me years ago that he had met Hervé and they got on really well together and he photographed Hervé, but he never printed the photo. So he looked for it and he never found it and then years went by. And when I started working on this, I was like, “Wouldn’t it be great to have a Duane Michals author’s photo?” So I asked him again, and he described the photo, “It’s Hervé in Venice, and he’s on a bridge,” and the description is very vivid. And then he said, “I’m going to look for it again.” Time went by and I realized, “Okay, I guess he’s not going to find it.” I mean, it’s okay. Duane is in his early 90’s. But a few weeks before we went to print the book, I got an email from him like, “I found it.” And he sent the photo and it was just amazing to see. I realized he’s around the same age he was when he actually was working on Suzanne and Louise. And the handwriting in the original must’ve totally been influenced by Duane because he was one of the original people to use handwriting along with photos. So I think Hervé really looked up to Duane. It felt fitting.

BEIN: Yeah, that’s really special. Wow. I really wonder what all of his contact sheets looked like.

WEITZMAN: I know.

BEIN: It’s been really lovely getting to hear about this book.

WEITZMAN: Yeah. I can tell you’re into it.

BEIN: He was so prolific, but there is a finite amount of his work available, so I want to take it slowly. Suzanne and Louise fills a really big gap his biography for me.

WEITZMAN: It’s true. It gives this other side of him.

BEIN: I mean, I also feel like I’ve fallen in love with him.