GAY

How Marwan Kaabour Wrote the Definitive Guide to Queer Arab Slang

When Marwan Kaabour was growing up in Lebanon, a mean kid called him “foofoo”—the English equivalent of “sissy”—a word he had never heard before and didn’t understand. Even at the age of five, he could sense it was negative, intended to pass judgment. At the time, he was confused and hurt, but that insult opened a door to another world, sparking in Kaabour a lifelong interest in queer terminology specific to different Arab regions.

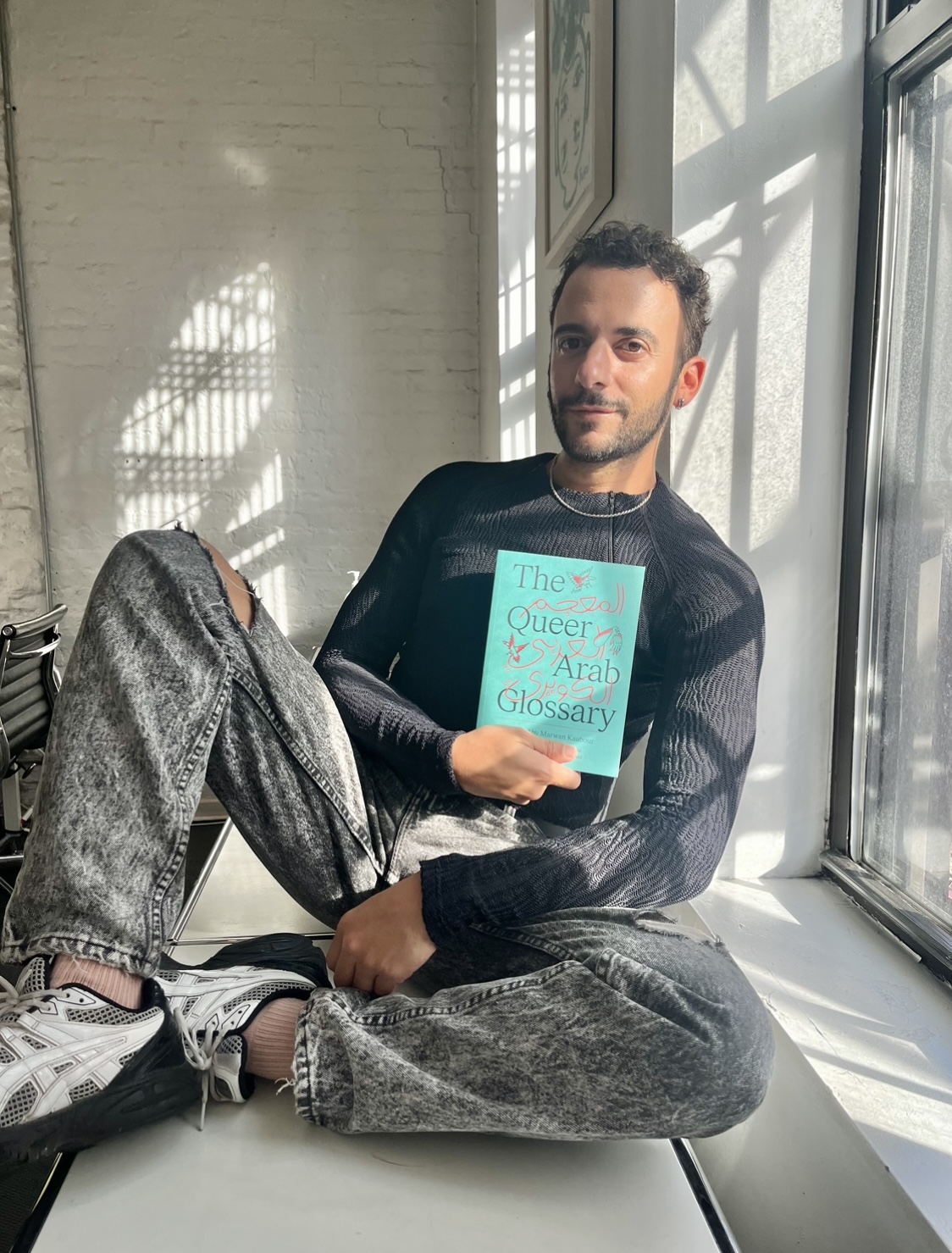

Fast forward to today and Kaabour, now London-based, is an accomplished graphic designer, best known for Phaidon’s oversized 504-page tome, The Rihanna Book. On the side, he’s also a passionate queer linguist and historian. In 2019, he founded Takweer, an Instagram account used to gather and share LGBTQ+ information and history. Recently, his professional skills and personal interests came together in his first book, The Queer Arab Glossary, a groundbreaking anthropological work that celebrates the diverse queer cultures of the Middle East in all their sleazy glory.

When Kaabour arrived at my office dressed in a sleek GmbH sweater, the handsome flirt was brimming with enthusiasm. He’s in the U.S. for a month-long book tour, with stops at New York University, the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, and Harvard. Everywhere he goes, he’s receiving joyful affirmation, especially from young Arab queers delighted to finally see their specific style of gay culture reflected back at them.

———

MICHAEL BULLOCK: How long have you been in New York?

MARWAN KAABOUR: Just under a week. It’s been busy. New York is the first stop of my month-long North American book tour, which started last week at the Leslie-Lohman Museum here in Manhattan.

BULLOCK: How’d it go?

KAABOUR: It was amazing. It was really filled with people. We had a panel discussion that was really good. Hussein Omar, the Egyptian writer and historian, was moderating. I’m sure you know him well.

BULLOCK: Yeah. Hussein told me he wanted to do a queer Arab art history book.

KAABOUR: Yeah, our fields of research overlap a lot. We’ve been conversing virtually, but this was the first time we had an in-person engagement with our works. And then the panel included Suneela Mubayi, who’s the Glossary‘s editor; Maya Mikdashi, a Lebanese scholar at Rutgers University at the Women and Gender Studies Department; and Andrew Makadsi, an art director of Lebanese origin, most known for being Beyoncé’s art director. Since we’re doing the event in the States, it was interesting to bring all of these different voices in.

BULLOCK: And it was oversubscribed by double?

KAABOUR: It was. I come from Beirut. I have very big ambitions, but when you put something out in the world, to know that it’s traveled so far and can still have a moment is really special. I’m new to this world. I don’t know how these things work.

BULLOCK: But you’re not new to designing books. You’re just new to launching books?

KAABOUR: To publishing myself, yeah. I’ve worked on very popular books, but this is a book with my name on the cover. It’s research I did for a very, very niche subject matter, so I did not anticipate how the rest of the world would deal with it, especially people who are not queer or Arab.

BULLOCK: The book is groundbreaking. Nothing like this has ever existed before, and there’s thousands of years of gay culture to be unpacked.

KAABOUR: Discussing queer identities has come to the surface, I would say, in the last few decades. So historically, it’s been neglected. And add the Arab element, where our identities have been flattened to two quite boring, lame narratives of either being a victim or a Western import. My job was to provide the more nuanced, multifaceted story that I know has always been there.

BULLOCK: Who were some icons that you have shined a light on that I would not know, as an American?

KAABOUR: I highlighted Bassem Feghali, who is Lebanese. People refer to him as a female celebrity impersonator to get away with things, but he’s basically a drag queen, and he’s been doing it since the early ’90s. I would argue he’s more prolific than RuPaul.

BULLOCK: Wow.

KAABOUR: He entered the mainstream from the beginning and fooled the entire Arab population into adoring him just by switching up the terminology. He’s like, “Oh, I just impersonate celebrities. It’s a form of entertainment. I’m not trying to challenge your understanding of gender and sexuality here.” So he can get away with whatever he wants. I would also like to pay tribute to Hanan El Tawil, who is an Egyptian trans actress who was in several films in the early ’90s and then tragically died in a mental health facility, and they don’t know the exact circumstances. But the film industry in Egypt embraced her, and she appeared in many films. Obviously, she would always have this comedic streak to her roles as a trans woman, but this was the early 2000s. I don’t think you were getting nuanced representation of trans actresses in the States at that time.

BULLOCK: No, definitely not. There was The Crying Game. That was actually the most positive trans representation. And also Silence of the Lambs.

KAABOUR: Of course. That was my first encounter with a trans person on TV. I loved that, though.

BULLOCK: Is this book dangerous for you to put out in the Arab world?

KAABOUR: No.

BULLOCK: I guess it’s different in every country, right?

KAABOUR: It varies across countries, but it is not dangerous. When I put out a work like this, and I’m being vocal and public about it, it’s because I know I have nothing to lose. My family is down with it. My friends are down with it. I feel secure and independent. I live in London. I have enough of a safety net to confidently put out a project like this. It’s available in Lebanon in mainstream bookstores like Barnes and Noble or whatever.

BULLOCK: Have you done a book launch in Lebanon?

KAABOUR: I did, and my parents were there. It was incredible.

BULLOCK: What was their reaction to the book?

KAABOUR: It’s funny because I guess a lot of our parents are like, “I don’t really know what you do, but I’m happy for you.” But then when they came to the book launch and I could see the transformation in their eyes. It was really beautiful. They’re like, “We get it now.” And they’re very proud.

BULLOCK: You started with an open call for people to send in their own terms, right?

KAABOUR: Yeah, that’s how the process began. I put out a call asking people to submit words and terms in their own dialects referring to queer people in any way, good or bad. Arabic is not one thing to everyone. So as you move from one country to another, the way we express ourselves in dialects varies massively. And in the end, we have 330 in the book.

BULLOCK: In the foreword, the writer [Rabih Alameddine] said, “One of the first things any group does when forming an identity is play with language […] They will change dialects, invent words, introduce new meanings to them.” I think every group of people can relate to the process of making language their own.

KAABOUR: Exactly. Language is like this. I draw a lot of parallels between queerness and language as these fluid, boundless, limitless concepts that are always changing and being redefined over and over again. We shape language like Play-Doh rather than it shaping us. We are the ones who decide. Even you and your family might have your own lingo. It’s a way of emboldening the social ties between a specific group of people who choose to be together. That’s why I think it’s universal in its reach. Any group of people can reflect on what that means to whatever group they belong to.

BULLOCK: Absolutely. And in your foreword, you said the first word you heard was foofoo?

KAABOUR: Foofoo.

BULLOCK: And it means—

KAABOUR: Sissy. That word was popular at the time, and that was said to me as a kid.

BULLOCK: Kids called you Foofoowhen you were five and you didn’t know what it meant.

KAABOUR: Now I don’t mind it at all, but at the time I was like, “What do they mean?” As more people would mention that word, I would see the way they’re saying that word to me, and it kind of clicked in my mind. I was like, “Oh, it’s not a compliment.”

BULLOCK: Was this your first experience of gay lingo?

KAABOUR: Basically.

BULLOCK: And from there, you would ask your father the meaning of words in context.

KAABOUR: And the etymology. My father is a musician but also used to teach Arabic in school. He was obsessed with Arabic. So whenever I’d ask him about a word, not only would he tell me what it means, but he told me the whole historical background of every word and the etymological roots. In that way, this is very much a continuation.

BULLOCK: So this project combines all the factors of your life.

KAABOUR: Book-making is about storytelling to me. It’s like, “What’s the rhythm? How do you build a crescendo? What are the graphic components?” It’s like making a song or a movie or a poem. The only difference is usually I receive material from people and I spit out a book for them. But this is the first time I was also the conductor of the material.

BULLOCK: How does it feel?

KAABOUR: It feels fucking incredible. I worked four years on it. I poured so much love and time into it. Every moment working on this book was absolute joy. I knew it would resonate with people, but especially with the queer Arab community. What I did not expect is such a broad appeal. And for that, I’m very grateful.

BULLOCK: Well, I think we’re at a point in American gay culture where it feels a bit burnt out, and we’re starting to look to other places to gain a better understanding of different cultures.

KAABOUR: Absolutely. I think one of the first things I learned when I began engaging with people about this book is that queer discourse has been co-opted and commercialized and removed from any sense of radical or revolutionary energy that originally came with it. Stonewall was the heart of it.

BULLOCK: In New York, they started a counter parade because so many people thought the mainstream Gay Pride Parade was too commercial. The first year, the alternative parade had a banner over their stage that said, “No one’s free until we’re all free.” And the banner over the stage for the mainstream Pride parade said, “Acceptance Matters, MasterCard.”

KAABOUR: Oh my.

BULLOCK: I was like, “This is it in a nutshell.”

KAABOUR: Basically. But I’m sure in two years the counter parade is going to become co-opted too, so you have to continuously push against it and start looking outside of the Western bubble, because other places have such different trajectories to their queer liberation and there are lessons to be learned.

BULLOCK: On a side note, I was in Bogotá yesterday and I went to their sauna called Cómplices.

KAABOUR: Cómplices?

BULLOCK: I mean, major. Such a good name. And to enter Cómplices, you have to go through the Stonewall Museum.

KAABOUR: Wow. It’s like the gift shop is a sauna. I fucking love that.

BULLOCK: Education and pleasure going hand in hand. I highly recommend it.

KAABOUR: I need to go.

BULLOCK: I’ll show you pictures after we finish. I want to ask about the dirtiest terms. My favorite is khor.

KAABOUR: It comes from Kuwait and Oman, and it’s part of the Gulf dialects. Khor means a creek, and it’s a euphemism for the anus. It refers to a bottom who is so hypersexual, his hole is just constantly wet, like there’s a creek in it. There’s something quite raw about that word, so he’s basically just a hole.

BULLOCK: Unbelievable. I found some of these terms dirtier than English slang. . I wonder if the repression of gay culture in these areas created dirtier language.

KAABOUR: Maybe. I don’t know if it’s repression. I want to say that historically the Arabic language is so widely poetic and sassy and tongue-in-cheek, filled with metaphor and analogy. They just have a way of painting a picture with a word.

BULLOCK: That certainly paints the picture. That’s a nice segue into the visuals you chose for this book?

KAABOUR: I worked with a Palestinian illustrator, Haitham Haddar, who’s also an incredible tattoo artist. We’d go through the words, and we’d find the ones that would conjure up an image. The general idea was to create these queer mythological creatures, superheroes or villains, to allow young queer people reading the book to kind of dream of these stories. So khor, for example, is a scene that involves a very enraged looking orifice, which takes the shape of a swimming pool, and there’s a queue of very athletic-looking men just waiting to dive in.

BULLOCK: You’ve illustrated something very graphically, but in a way where your mother could still look at this book and not be offended.

KAABOUR: Exactly. Although, she did look at one picture of muntahin, which basically means the one who has been pounded to a crisp.

BULLOCK: What country is that word from?

KAABOUR: Also Oman, actually. And she looked at it and she’s like, “Why does he look so much like your father?” And I was like, “Oh my god,”.It does look like my father. We had to close the book.

BULLOCK: Is that Freudian?

KAABOUR: To her, maybe. To me, it’s purely coincidental. But it harkens back to an illustrated glossary, like in the old days. The idea is to take the sometimes very dark or grim meanings of these words and add a sense of humanity and complexity to it—

BULLOCK: And cuteness and humor.

KAABOUR: Yeah.

BULLOCK: Were there any outcomes from the book that surprised you?

KAABOUR: The amount of messages from young queer people who tell me that for the first time they have a record of their experience that seems in line with how they feel about themselves, rather than how the world is telling them they’re supposed to feel. The sense of belonging and the sense of community for them has been the most incredible thing. Just to know that something you did can make someone feel this way.

BULLOCK: Beautiful. And what’s the next book?

KAABOUR: God, I don’t know. This came out in June. I’m starting to toy with the idea of a more personal book, maybe a memoir of sorts.

BULLOCK: Is there anything else you want to say that hasn’t been said in other interviews?

KAABOUR: Free Palestine. As queer people, our very existence stands in opposition to the dominant forces that we’re fighting against, the forces that have capitalism and patriarchy at their heart. So as queer people, it’s our responsibility to stand with those who are facing the impact of these brutal forces. So I call on everyone to educate themselves and to stand with us against these forces. Sorry to end on a serious note, but it’s my reality.