LIT

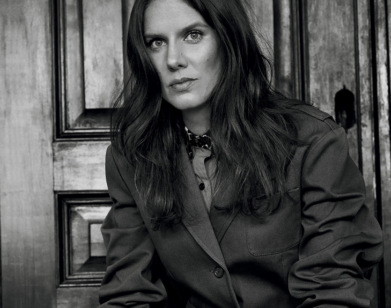

“Grief Has No Timeline:” Writer Sarah Gerard, in Conversation With Leslie Jamison

“We can’t possibly foresee someone in our life dying,” says Sarah Gerard. “That, in itself, is unthinkable.” But in September of 2016, Gerard’s friend, 25-year-old Carolyn Bush, was brutally murdered in her New York City apartment by her roommate Render Stetson-Shanahan. Bush was an aspiring writer, and Render thought to be a somewhat reserved art handler. Nobody could have anticipated either Bush’s killing or Stetson-Shanahan’s violent disposition; so shocking was the event that author Sarah Gerard went looking for answers. Her latest book, Carrie Carolyn Coco: My Friend, Her Murder, and an Obsession with the Unthinkable, is, in part, a true-crime investigation, but also a carefully assembled portrait of a young woman whose life was senselessly cut short. “I wanted to keep knowing her and this felt like a way to continue getting to know her even though she was gone,” she explains.

For Gerard, this is a book that has been difficult to promote, if even harder to write. “The grief hit me all at once in the end,” she told the acclaimed author and essayist Leslie Jamison, “because I hadn’t really allowed myself to grieve, but I was absorbing everybody else’s grief all this time.” In writing Carrie Carolyn Coco, Gerard not only acted as an investigative journalist, filing FOIA requests and auditing Bush’s old LiveJournal blogs, but an elegant storyteller, too, weaving a tapestry of Bush’s life out of interviews with her friends and family across Florida, Ridgewood, and the Hudson Valley. “One of the things that I appreciated both on an ethical level and a craft level about the book was the space granted to all of these voices,” remarked Jamison when the two got on Zoom last month. In their discussion, edited below for length for clarity, the two writers explore grief, tragedy, and the arduous, intensely emotional process of bringing Carolyn Bush back to life on the page.—JULIETTE JEFFERS

———

LESLIE JAMISON: I don’t know how many interviews you’ve done so far, but I’m wondering how you’re feeling about the book coming out, and whether you feel like you learned things about taking care of yourself in the process of writing that will be useful to you as you undergo the process of putting it out in the world.

SARAH GERARD: This is the second interview I’ve done, and the first one was just two days ago, so it’s still really new. I feel so much reticence and apprehension around promoting a book of this kind. Because how do you promote the story of your friend’s murder and all of the people suffering in the wake of it? It took seven years to write this, so everything in my life changed during that time. I went through a divorce and got married again, moved across the country twice, made friends and lost some. And some of that was because of this book. There was just a complete seismic shift while writing it. When Carolyn died, my first husband had cancer and we started smoking weed together. It became a crutch for me. And then we got divorced. Cancer was the last straw in that marriage. And over seven years, marijuana became more and more of a crutch for me. Until January of this year, I was like, “I can’t do this anymore. It’s so expensive. It’s clouding everything in my life.” This book had brought me to a place of just severe depression and anxiety by the time I was finishing it. I got Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Therapy, which kind of sounds like shock therapy, but isn’t. Have you heard of it?

JAMISON: No, I haven’t.

GERARD: I feel like I’ve joined a cult, I’m telling everybody about this. It’s a huge magnet that they put on your head and point it at your prefrontal cortex to stimulate it to grow in certain areas that control depression, anxiety, PTSD, OCD, all of which I feel like I had by the time I finished this project. They also use it to treat addiction. So I quit smoking weed, started getting TMS therapy five times a week, went through that for six weeks, and I haven’t smoked weed since January.

JAMISON: First of all, I’m glad that it’s been able to help you in that way. I find it so powerful to hear you talk about not only how you were essentially writing and working on this book from the inside of so many different lives, but also the ways that a project can sometimes demand the reinvention of one’s life. I feel like The Recovering was a similar time span, about seven years. I wrote it from inside a series of very different lives, domestically and otherwise. Maybe the depression and anxiety that working on this book would very intuitively plunge you into might be most acute when you were just finishing up. You tell me, but there could be a real adrenaline rush in just the sheer work of it, of making it and doing all these interviews and spending time at the trial and doing all the research and doing some of the remembering and putting it all together.

GERARD: We’ve all experienced trauma. That’s why we’re artists, right? You can’t really react to a trauma until it’s over and you have that safe distance to fall apart. So finishing the book was… How do I say this? The grief hit me all at once in the end, because I hadn’t really allowed myself to grieve, but I was absorbing everybody else’s grief all this time. And also, because grief takes so many different faces: sometimes it looked like sadness, sometimes it looked like denial or avoidance or anger. I was asking everyone to point it at me so that I could understand it. At the same time, sharing the work with people afterward and asking them to react to it was something I wasn’t completely prepared for. You can’t control how people react to your writing at all. Every one of my books has made some people angry in ways I never predicted. I just have to have empathy for that, hold space for it, understand it, love anyway, and try to be confident in what I’ve done. Grief has no timeline, it has no pattern. And the irony of writing a book about somebody who pleaded marijuana-induced psychosis while I, myself, was smoking copious amounts of high-THC weed all day is not lost on me. But it did force me to take a really good, hard look at myself. And that was not something I could’ve done while I was writing the book.

JAMISON: Just in case you need to hear it again, I will say it. This book is such an important document to exist, and it will be important to so many people who have had their lives impacted by violence in a thousand ways. The job of art and even the job of documentation is not to please everybody. It’s an impossible task.

GERARD: I get the sense that you’re like me, a people-pleaser. I’m an only child, so I want everybody to like me and I don’t want to be alone and rejected. I hate when people are mad at me, it’s the most difficult space for me to sit in.

JAMISON: Yes. I wanted to ask you about this idea of “the unthinkable,” because, as a writer, a subtitle– especially in the world of nonfiction– can so often feel like compromise or concession. But I love yours, I really do. There’s a bluntness to the first two beats, “my friend, her murder.” You force a reader to face head-on the same tragedy that you’re facing head-on, and that so many of the survivors and loved ones had to face head-on. Then there’s this final beat, “an obsession with the unthinkable,” that does so much work. It points a certain question back to you as the narrator: “How have I become obsessed with this murder?” So I wonder if you could talk a little bit about what “unthinkable” means to you and why it was important to frame this book that way.

GERARD: It’s all of those open-ended questions that I tell my students to meditate on while they’re writing. “What made this happen? What happens now, and why?” It’s a cultural problem of racism and male violence and corruption and institutionality, and conspiracy, how we cover it up and enable it and perpetuate it. It’s the way that we can’t possibly foresee someone in our life dying. That, in itself, is unthinkable. We can’t possibly imagine how we’ll react to that, what our lives will become in the wake of it. As a memoirist, I had to really look at how this project, in a way, centers me as the writer, but how I didn’t want to be centered as a character. I think it made a lot of people uneasy, the fact that somebody was writing about it. A lot of people declined to talk to me, actually, which I can’t fault them for.

JAMISON: It’s a beautiful response and points in so many directions that feel close to the core of the book. One of the things that I was struck by when I was reading the book was how the style was working. I was so impressed by the breadth and depth of the reporting, the interviews, the trial coverage. But also, the stylistic restraint. As a beautiful prose stylist, it felt like you were conjuring a different kind of voice for this project that was, among other things, calling attention to itself as little as possible. I kept thinking about that moment from Lolita, Humbert’s famous [line], “You can always count on a murderer for fancy prose style.” There are deeply troubling links between style and violence in that book, dressing up violence in the finery of style. How did your style here depart from your style in your previous books?

GERARD: I think you said it really well, it’s not a voice-driven book. The full manuscript was actually 550 pages and my editor was like, “I’m not going to fucking read that. You have to cut out at least 200, if not 250.” And I did the best I could. One of the people that I sent it to told me to put more of myself in the book and it just made me very uncomfortable to do that. I really wanted to get out of the way of the writing and let the facts speak for themselves, because they do very well. Also, I wanted to let Carolyn’s loved ones speak through the work, which meant that I had to get out of the way. This work went through so many phases of form. I wrote a proposal for it in 2020 after the trial ended, because I felt like I had to know what the story was before I started writing it, which is not usually my process. It was only after I sold that proposal that I could actually afford to buy all of the trial transcripts and get the interviews I had done thus far transcribed. All of that ended up costing me like $24,000 or something– I basically spent my entire advance on more reporting. Once I had all of that, I felt so overwhelmed with the sheer amount of material that I considered just writing the book as an oral history. I wrote 150 pages in this oral history style, but it wasn’t cohesive enough. I think the repertorial voice of the book just comes out of the demand that I synthesize everything. I wanted to give power back to Carolyn’s loved ones. I felt like it would’ve been another kind of violence to step in and tell everybody’s story for them.

JAMISON: One of the things that I appreciated both on an ethical level and a craft level about the book was the space granted to all of these voices, which I know is not always an easy feat in an interview– in part, because of what you were saying earlier about grief, that grief expresses itself in so many different ways. It’s almost like the easiest expression of grief is just the open, direct expression of sadness, but that’s one of the rarer ones, really. You created both the conversational conditions where people can speak to some of these difficulties and then created the textual conditions, a map where their voices can all exist in the arc. I wonder if you could just tell me a little bit about the origin story of the book. Not just starting to write it only once the trial was done, but when and how you knew you wanted to write this book.

GERARD: It was early in 2017 that I started to feel a sort of ineffable… What’s the word I’m looking for? A bunch of flashing green arrows pointing in the direction of writing a book. I was looking at all the different areas of Carolyn’s life right away: Wendy’s Subway, New York City, her Florida people, her Bard College people. Having an investigative plan makes things a little easier. I could already see how the plan was forming without my having to really do anything. I could see who I should talk to first and where that might lead me next. I saw this cast of characters in our hometown, some of whom I knew and some of whom I didn’t. I could never have predicted how difficult it would be, but I could see who I should talk to first. In the beginning, the reporting was pretty gradual because I was writing another book and I was promoting a book at the time, too. And then, towards the end of the project, it really accelerated a lot. I was put in touch with someone who started telling me things about Bard that were absolutely flabbergasting and horrifying. At that point, I knew that people from Bard had written letters of support. I had gotten one batch of letters, written in 2020, but I had not yet gotten the second batch, the letters written earlier, in 2017, before Render was indicted. It would be December 2021 that I received an accidental FOIA request response for the second batch of letters, which I didn’t even know I was requesting. I got really, really upset because I didn’t know I was even waiting for these, and they were worse than the first batch I had received. Anyway, I forgot the origin of that question.

JAMISON: No, the origin of the question was around origins. The other thing that I was most urgently wanting to ask was about your wanting to evoke Carolyn through and inside of these multiple worlds. The world of Wendy’s Subway, the world of her life in New York City, the world of her hometown and her Florida life. It felt like an act of resistance to violence. One of the things that violence and murder do is erase someone—not erase them in memory, but deny them the continuation of the life they’re living. So to let her be defined by history, by community, by relationships, by specific details—how did you come to that?

GERARD: Well, right away I knew that I wanted to tell her life story because I could see it emerging from the very beginning. I had this foundational understanding of at least part of her life, because I had lived in that same space as her for all of my childhood and even part of my adulthood, too. Like I said in the book, I wanted to keep knowing her and this felt like a way to continue getting to know her even though she was gone. I could talk to people about these different parts of her life that I wasn’t present for and collect these stories and build this patchwork. So it just felt like retracing the steps of her life as much as possible to see what it felt like to live it as her.

JAMISON: I love that idea of the patchwork that has both the pieces and the sources and also the spaces that acknowledge unknowability. The way you were talking about all this work of reportage and excavating her life history makes me think about this line from Charlie D’Ambrosio. The essay engages with his youngest brother’s suicide note, and he talks about the emotional dimensions of becoming a textual close reader of that note. He says, “I wanted to keep reading that note forever because it was a way of remaining in conversation with him.” The work of learning and walking those streets is a way of remaining in conversation.

GERARD: Yeah, walking the streets of Carolyn’s mind and her life. I collected as much of her writing as I could. Sometimes people told me where to find it or sent it to me. Sometimes people mentioned that something had existed and I went looking for it. I found out she had three different LiveJournals. I wanted to put as much of her voice in the book as I possibly could. Some of that ended up coming out through conversations that people told me about having with her over text or over email. But she was always so witty, even as a 13-year-old writing on LiveJournal. She had this poetic flair that I just found really interesting. One of her boyfriends told me, “She’s smarter than both of us.” It’s true.

JAMISON: One of the things that I appreciated most about your portrait of Carolyn, and one of the things that actually felt most distinct about your book as an account of violence, is that we never reach the end of her infinitude. When I was reading it, I was so in the midst of living in her world, in the midst of the city, talking to waiters about being a Scorpio, eating organ meat, in the midst of getting a degree and these relationships and intimacies that were existing in liminal spaces. It really, for me, just ached with the tragedy of all of that unfinishedness.

GERARD: The word that comes to mind is “redacted.” She was just snatched from the middle of her ongoing existence. We can never really know what her life would’ve been, and that’s the tragedy of it.

JAMISON: As I was reading your book, I kept thinking about something that an editor once told me when I was first starting to do any kind of reporting work. My editor was like, “You need to answer every question that you possibly can so that the unanswerable questions carry their weight, so that they feel distinct and profound and genuinely unanswerable, rather than getting lost in the clutter of a bunch of other questions.” There are so many unanswerable questions at the core of your book, but the breadth and depth of your reportage allows those unanswerable questions to feel so profound and fully earned because you’ve given us so much of what you could learn. As you know, I am obsessed with specificity as a point of craft, and I write about it a lot. You’re also very much a writer of specificity. So often, people are prone to speaking in vagueness and abstractions, especially when it comes to wounds and deep, unresolved pain. How did you understand the importance of detail in terms of evoking violence?

GERARD: That’s a good question. Well, I’m a little bit obsessed with facts. I work as a private investigator, so fact-finding is all of my work. I have to know “when” and “where” and “what” and “why” and “how” and “who.” I am always asking for more witnesses, looking for the surveillance video, asking them to pinpoint the exact location where something happened. When I was sitting with people and asking them questions about Carolyn, I was asking them for specific stories about her life. I told them that I wanted to weave a story of her life, and in order to do that, I need moments. Those moments are made up of facts, too. I’m thinking of the story of her driving across the state to watch the sunrise with her friends and how sharing that story with Pamela [Tinnen] prompted her to share that very same story with me. “Oh, I drove across the state with Jenny, and Carolyn never would’ve done this had we not done that first.” So it told me something about Carolyn in return. I wasn’t there for that drive across the state with Carolyn and her friends, but when I was sitting with her friend, hearing that story, she was actually showing me photographs from that trip, and I was recording our conversation, so I got some of those descriptions. But also, because I was solving a mystery and was on an investigative mission, I needed as many facts as possible, almost like I’m making a case as a prosecutor myself. I’m making a case about Carolyn’s life rather than about her death.

JAMISON: What kind of case did you feel like you were building about Carolyn’s life?

GERARD: Maybe it’s as simple as saying her life deserves to be the focus of this book. It’s hard writing a book like this because it’s not as though Carolyn is already known to the general populace. She’s not a celebrity. She’s not Barack Obama. It’s not like people are going to be flocking to the bookstore to read a biography of Carolyn Bush, but I want to convince them that they should.

JAMISON: It’s so easy to offer a kind of lip service to the idea of granting a victim a fullness of identity beyond their victimhood, but to actually do that is tremendous work. I could keep asking you questions forever, but I also want to respect that it’s intense and—

GERARD: Yeah, it’s intense.

JAMISON: Actually, what you just said about Carolyn not being a household name, what does it take to write a book that’s asking people to think about her life? I love the title of the book so much. It feels like it has this elegiac, lyric force to it. I wonder how you came to it and what you wanted to express about Carolyn’s identity through this naming of her three times. It almost feels like an incantation.

GERARD: Actually, I had the title before I even started working on the research. I was reading all of these different people’s posts about her on Facebook and hearing various people talk about her at her memorial, and they were using these names. I kept thinking about them in a chronological order as a series of progressions, or these different versions of Carolyn that she became over time, and how she was caught in the process of becoming “Coco” when she died. A name says everything about you. I remember when I was a preteen, for this very short period of time, I was curious what it would feel like to have a different name. I started asking people to call me “Liz,” which is an abbreviation of my middle name. I hated it. It just didn’t fit me at all, but I thought “Sarah” was so common and so boring. So anyway, I just felt like there was so much that I could glean about her personality from this exploration of her name progression, who she wanted to be, who she used to be.

JAMISON: That idea that she was caught in the midst of becoming “Coco”—there’s so much glamor and self-possession and playfulness and wit in that name.

GERARD: Because of Chanel, it’s so classy.

JAMISON: Yeah.

GERARD: There’s something rich and mysterious and French about it.

JAMISON: Totally. I am curious to hear a little bit about how this book and project fit into the arc of your creative and professional life. There are more obvious ways in which it’s a departure from your previous books, just by nature of what it is. But I’m also curious what continuities you see, if any.

GERARD: As a writer, I’m really addicted to story, and I try to write poetry, but it doesn’t come out very well. So I see fiction and nonfiction as being like conjoined twins, I suppose. They kind of emerge from the same place of story, but they have different minds. My dad was an investigative journalist, and my grandfather, his father, was also a writer of fictional stories. My great-grandfather on my mother’s side published several nonfiction books and was an editor for Scientific American. I think part of it is just genetic. I’ve inherited this tendency to write, and both my parents are very, very literate people. They read constantly. My dad reads the entire New York Times every day, and he’ll read it aloud to you at the breakfast table if you let him. My mom is always sitting around with a book in her lap. She also volunteers at the library. My parents have been in the same book club for thirty years. I grew up around stories and always knew that investigative journalism was something that I could do because it was in my family and I had somebody in my house who could teach me how to do it. So when I graduated from college, I became a freelance journalist in Tampa Bay. And at the same time, I was writing a novel about a near-death experience that I’d had in my early twenties when I jumped from a moving freight train and landed on my face. But journalism has always been there, and I think it’s always come actually a little bit easier to me than fiction. Fiction sort of seems like shining a flashlight in the dark, whereas journalism feels like writing down what I see in broad daylight.

JAMISON: People give you a hard time if there’s not enough trauma in your memoir. But where do we believe art comes from? Does it come from the wattage of events or does it come from how we find language for experience? It seems to be a real double standard.

GERARD: I think it’s just another one of these unanswerable questions. All of my fiction is on some level autobiographical. Even though I’m piecing together my real experience with shit that I made up, at the core is my real experience. I think people believe that’s cheating or something. Autofiction is derided for being sort of a feminine practice, but at the same time, nobody’s out here criticizing Ben Lerner for writing autofiction. When a woman does it, it’s not as artful. And I just think that’s bullshit.

JAMISON: Yes, yes. It feels like sustenance to hear you talk about it. Okay, I could seriously keep talking to you forever.

GERARD: Let’s keep talking forever.