LIT

Diane Seuss on Punk, Plath, and the Poetry of Rage

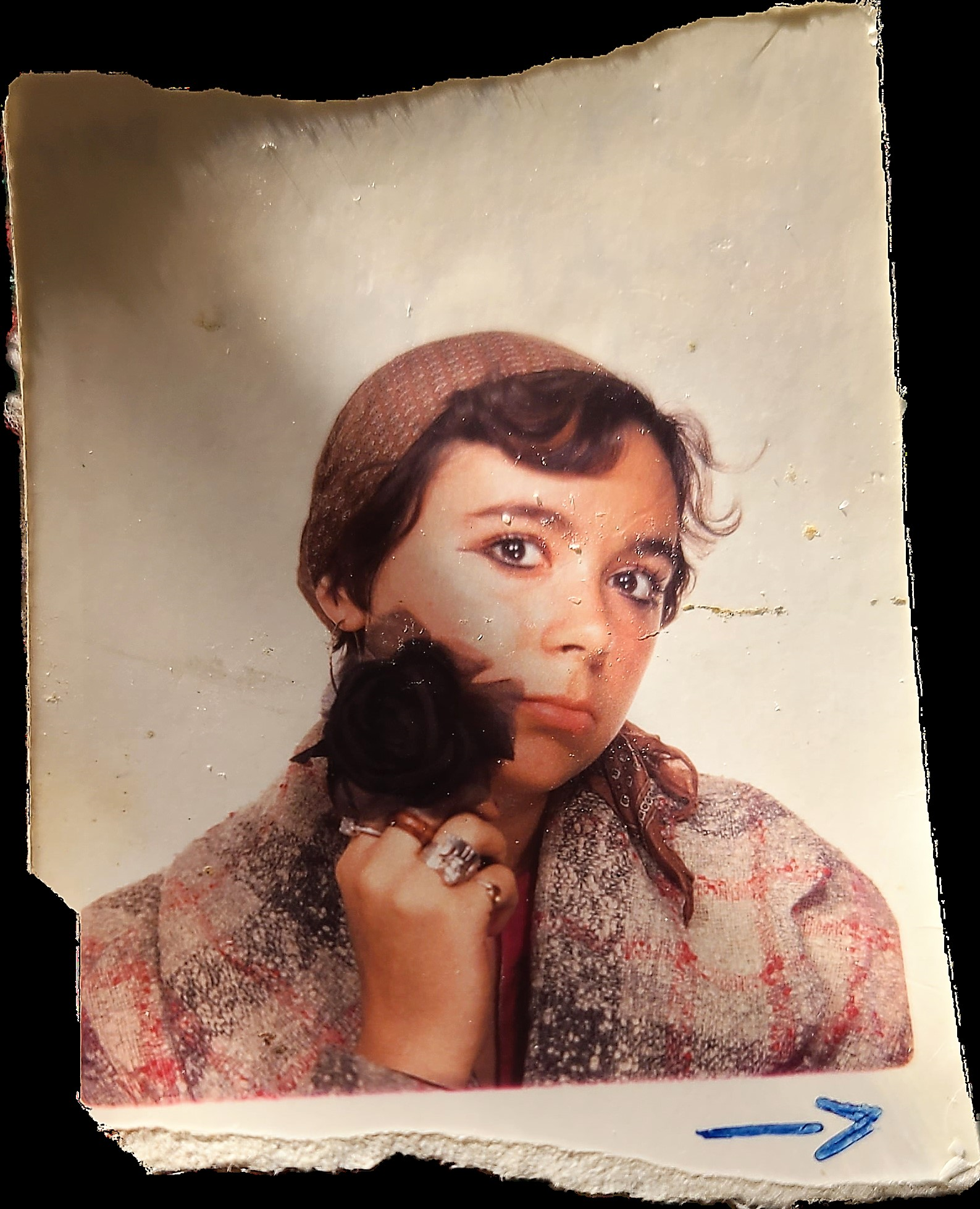

Modern Poetry is Diane Seuss’s parody of a textbook, though both textbooks and poetry books tend to avoid putting their authors on the cover as of late. When I asked Seuss about the cover of Modern Poetry, she explained that it was a polaroid of her at eighteen, kept in the billfold of her mother’s wallet for some 40 years. In the photo, Seuss gazes intensely, adorned with the dark-winged eyeliner she adopted in high school after playing an accused witch in a production of The Crucible. In Modern Poetry, Seuss references this younger self, someone “who felt like an abject outsider but also thinks she may have something to say,” as she explained over Zoom earlier this month. Modern Poetry does not disappoint in its embodiment of punk spirit; even as Seuss embarks on the essentially academic task of uncovering the fate of modern poetry, she summons the great lyric poets of the past. “In this book, the dead feel that the living are very overdone,” she says. “We’re very weighty. We’re very fevered. So coming to objectivity is a hopeful gesture.” Keenly aware that the project of life is inherently messy, she hopes that at least the dead might find it less so. But mess is something that Seuss has never shied away from, whether she’s writing about St. Marks Place pre-Giuliani or reading Collete in a cabin without running water. She has the rare talent of quoting Keats from memory and sounding genuinely casual, and both were on display when we got on a call to discuss Plath, the poetry of rage, and her brief encounter with Andy Warhol in Washington Square Park.

———

DIANE SEUSS: Sorry, I’m coughing. I don’t think it will last. Say I’m a consumptive woman poet who likes to fall back on a couch when I’m in the blues.

JULIETTE JEFFERS: That would go with some of the themes of the book.

SEUSS: It would. Where in New York are you living?

JEFFERS: I’m in Brooklyn right now.

SEUSS: I like Brooklyn. When I lived in New York, the young hip people didn’t live in Brooklyn. They lived in the East Village or the Village, but now nobody can afford to live there, apparently. I had a rent-controlled apartment and it was so dirt-cheap. I mean, it was terrible, but it was cheap.

JEFFERS: Where was it?

SEUSS: On Second Avenue and 7th, right near St. Mark’s Place. It was punks. It was not gentrified. It was not cleaned up. It was a mess. But I liked it being a mess. It was pre-Giuliani.

JEFFERS: You write about that in frank: sonnets. You have a whole poem that gets into St. Mark’s.

SEUSS: Yeah, I do. My first night there in New York. And in Four-Legged Girl, my first book with Graywolf Press, the sort of hub of the collection is called, “I can’t listen to music, especially ‘Lush Life.’” It’s about the relationship I had when I was there and how that all unfolded.

JEFFERS: There’s a lot of music in all of your books, but particularly in this book. One of my favorite poems in the book is “Cowpunk,” which I thought was a brilliant title.

SEUSS: I am sort of a combo of a punk and whatever a cow represents, like the country-punk cursing thing, you know?

JEFFERS: The punk spirit of the Midwest.

SEUSS: Which does exist, and it doesn’t come through in the same way as the Ramones or whatever. But it does exist.

JEFFERS: This whole book feels like a Cowpunk book, in general. It feels pastoral at some points. There’s a much greater focus on these places that you lived that were not in cities, and you get these motifs of lambs, apples, attics falling apart. One of my favorite images in this book is the speaker recalling performing these childhood plays in a field, and this sense of that landscape giving permission or license to suffer in public.

SEUSS: Oh, I love that. Well, when I got into high school, there was a theater teacher and he was such an iconoclastic presence. He was gay and was really brilliant and extremely imaginative when it came to theater. He took this motley group of rural kids who had never seen a play and made these incredible little dramas. I was still kind of shy. I was walking down the hall one day and he came up to me and he was very handsome, and he said, “I want you to try out for my next play and just do it. You don’t even have to do anything. Just show up.” And so I did. I did a lot of theater with him, including the play that’s mentioned in “Cowpunk,” which is The Crucible. I remember just getting to scream in the lecture hall where we put on the plays. And after the play, I would just break down every time, like all this release and the excitement of being wrong and a witch and expelling all this emotion in public. I just wanted more. When I first put the eyeliner on, I looked in the mirror and said, “There I am.” And then I wore eyeliner for the rest of my life.

JEFFERS: That was your iconic look.

SEUSS: The eyeliner gave me a persona that was both protective and expressive and I dug that. I dug that feeling and it translated to poetry, that understanding that the speaker is not necessarily everyday me, but it’s a character or a persona that is based on me, in the same way that Whitman wasn’t so expansive and celebratory in daily life.

JEFFERS: Sometimes I wonder if he was really walking around like that.

SEUSS: I’ve read somewhere that he was shy. But I think he also had an ego. My ex-husband was shy with an ego. Sometimes it’s a bad combo.

JEFFERS: Whitman was really lonely, but he had these moments of ecstasy, and I see that in your work. I think there’s a poem at the end of the book—

SEUSS: Oh, the “lightbulb in the ass” line?

JEFFERS: Yeah, the light bulb in the ass. I loved the part about being the blunder, too. One of my teachers was once talking about your work and she basically said, “Diane Seuss is brave enough to not be the hero of her own poems.”

SEUSS: When I first started writing as a kid, I had to go through the period of writing about my wound. But I think that you wear that out after a while. It’s important to write about your wound, but then you have to go through various evolutions. And the evolution that I hit in frank and in Modern Poetry is different in that I am not the hero, certainly. I have no virtue. And some of that comes from raising my son largely as a single mother who became a serious, serious street drug addict. So owning my own sins, lack of virtue, I don’t think there’s any shame in that. Maybe there’s a lot of pressure on younger writers to sort of construct themselves as right, or right about things.

JEFFERS: I think there can be. But one of the things I appreciated about this book is it does make a lot of real assertions. As you were writing, was there any sense that you were definitively right in anything that you were saying?

SEUSS: No. With the state of being that I was in when I started this book, after frank, the world was very different than the world I wrote frank in. It wasn’t that long ago, but we were contending with sort of a form of fascism, which we still are, and environmental crisis, the pandemic, isolation. I have had a lot of aloneness that is unbroken. The first poem in Modern Poetry is “Little Fugue State.” It describes the state of the walking dead. “What is poetry, this dog, I’ve walked and walked to death?” So yes, I brought that question to the page—”what can poetry be against against suffering?”—and each poem takes a step toward answering that question. I think it gets answered in a very simple way by the last poem.

JEFFERS: I love ending with a funny poem.

SEUSS: Yeah. “Wiping his ass with his own hand.”

JEFFERS: It’s a hilarious poem, and it concludes this perverse love for romantic poets that you’ve been exploring throughout the book. There’s also this sense that modern poetry is waste. You have this line about modern poetry being cast off ovulations and lost lovers. These things that you lose, but still matter deeply. That feels essential to your poetry. The fact that in poetry there is always waste. There are poets that we would not think we would relate to at all, and yet we still do. It’s an incredible, resounding ending note.

SEUSS: Thank you. I think that’s where the whole book arrived, which is to say, you can say all this shit about poetry and poets, but you can’t argue with the Nightingale. I did a reading with Jane Hilberry and she was talking about how the wish of the book isn’t just to ask a question of poetry, but to recenter it among my people, whoever that is, or our people. And to revivify, transfuse it like Keats. That sounds egotistical, but it isn’t because I really don’t have really much faith in myself. But I have opinions, at least, about what poetry can be and ought to be and who it should not keep out, who it should open the gates to. I’m still working it out in my head. But the book is called Modern Poetry for a reason. First of all, it’s a parody of a textbook. I mean, it has my young 18-year-old, snotty-faced self on there.

JEFFERS: I was going to ask about the cover. So you were 18?

SEUSS: Yep. It’s me and my first year in college. And my mom kept that picture. It was a photo booth picture in her billfold for like, 40 years.

JEFFERS: Oh my god.

SEUSS: She’s 94, and when I was working on the book she said, “Look what I found.” And I made this decision that I want that on the cover. And I don’t think of it as me, per se, but this character who felt like an abject outsider but also thinks she may have something to say. In the beginning in that poem called “Modern Poetry,” I make the claim that I need poetry, but I don’t have the tools to get it. And the process of the book is like, “Well, what are the tools? What are my tools?” As I said in the poem, “My Education”: “when I needed Keats, I got him.” I knew what I needed for my project and my project was my life. It doesn’t mean I sat with an oil lamp studying every poem Keats ever wrote. I needed certain poems and the idea of Keats.

JEFFERS: I loved when you talked about poetic education as this cobbled-together, happenstance thing. Poetry is something you can study, but the poets that are important to us are important to us because we conflate them with the context in our lives in which we read them. Things come to us when we are ready to understand. In your poem about Colette, there is the sense that you have to be ready to receive it.

SEUSS: Yeah. I was reading Colette, as I infer in the poem, out in the wilds. I was staying in this little cabin, no electricity, no running water, outhouse, and I was obsessed with Colette, this French novelist. And what is it about her that lasted for me was less her books than her attitude. I don’t construct her in that poem as a good person, but this rousey-haired, so-called “exotic” writer who survived for a while surrounded by cats and cat hair. She was made to write by her husband. It was almost like indentured servitude or something, and then she became this free spirit. She spoke to me not as a good person or an elevated role model, but as somebody I could see in myself.

JEFFERS: Totally.

SEUSS: And then there is an Eve image, I suppose. The apple runs through this book, tearing the fruit off the tree of life and chomping it. And not everybody has access to the tree.

JEFFERS: No, there’s not always a straightforward way to that. You also introduce this concept of “poetry of rage and poetry of hope.” I think I see this in a lot of the women writers you reference, in Colette and Plath.

SEUSS: Well, “poetry of hope” that is divorced from or devoid of rage, it doesn’t ring true to me. And certainly now, it would be so easy to get swallowed by rage. I am, sometimes. I’m sure you are, too. If we were living absolutely, honestly, we would probably be destroyed by rage.

JEFFERS: You can’t be lucid all the time.

SEUSS: No. You’d go mad. I have already, many times. We can’t get to hope without an honest confrontation with rage and the things that ought to enrage us, and just feeling the electricity of our rage. Hope always feels kind of namby-pamby to me.

JEFFERS: Even the way the word sounds.

SEUSS: I know. Lorca talks about there being three kinds of spirits of poetry; one is the angel and one is the muse and the third is duende. The duende is the one he believes in as powerful and everlasting, and it’s dark and it drags its wings. Keats called it “negative capability.” It’s the same thing. Over-resolving into hope just doesn’t ring true, at least for me. For instance, in the last section of Modern Poetry, the poems do get to something. They get to objectivity and they get to a kind of love that is not the entrapments of romantic love, but larger and objective. And that runs through the whole book. Even in “Pop Song,” I’m re-confronting my dad who died when I was a kid, but in this version he’s sort of like, “Hey, how you doing?” There’s no intensity. There isn’t even love. And maybe he’s even kind of like, “Ew, what did I create?” In this book, the dead feel that the living are very overdone. We’re very weighty. We’re very fevered. So coming to objectivity is a hopeful gesture. Then in the poem “Gertrude Stein,” in the last section, the speaker comes to self-love, but it’s brief. “I love, as I once loved Tender Buttons,” that’s Gertrude Stein’s book, Myself. It sort of implies that I don’t anymore. This self-love, too, is tangential, but right then, right there, I love myself.

JEFFERS: I think there’s also a brief, strange moment of self-love in that section, where you’re like, “Oh, I think marriage never worked out for me because I was just waiting for my husband to die so I could find myself again.”

SEUSS: Yes.

JEFFERS: I thought it was so funny. You bring a really jaded, but also very feminine and honest sense of humor to everything.

SEUSS: Yes. I’m so glad you saw the humor because I think in a lot of ways, it’s the funniest book I’ve written.

JEFFERS: I’m sure there are many women who would relate to that feeling that you expressed.

SEUSS: When will we get to the “death do us part”?

JEFFERS: Exactly.

SEUSS: I never got the marriage thing down. Living alone through these last years has been really a challenge. But on the other hand, I couldn’t have written this book without it. This was a painful fucking book to write, even when it’s funny.

JEFFERS: I was reading it all at once and there are moments where I needed a break.

SEUSS: I need a break from this bitch. Can I tell you something before we end?

JEFFERS: Yes, of course.

SEUSS: When I lived in New York, I worked on Washington Square Park. One Sunday, I wandered into the park and I saw a Beatles cover band. The guys were all Indian, and I do mention that in the poem about my dad. I wandered into a gallery and it was a Warhol show, and there was Andy, giving away and signing copies of Interview.

JEFFERS: You met Warhol?

SEUSS: Yeah. And I said, “I love this art,” because I really did. And he said, “Oh!” or something. He did generate outward coldness.