Y2K

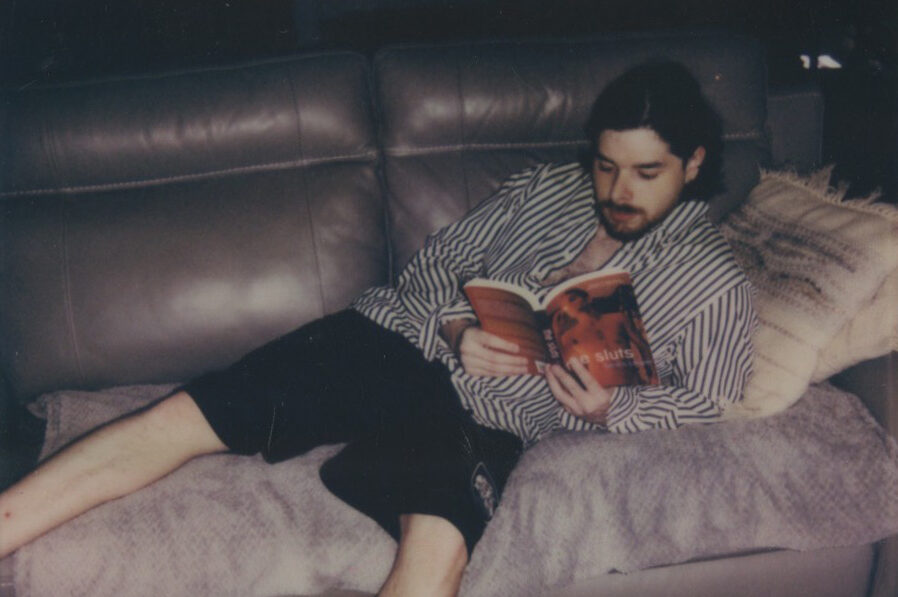

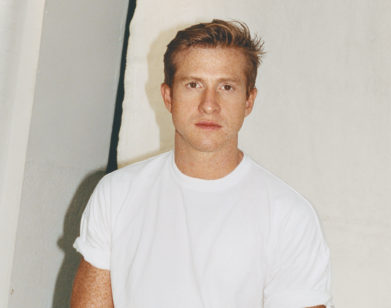

Alex Kazemi on Columbine, Content Warnings, and New Millennium Boyz

When I heard that Alex Kazemi’s novel New Millennium Boyz was set in 1999, I knew I had to read it. Last year, I sold my first book, a collection of essays about the years 1997-2008 called Y2K. As I’ve researched, written, and revised the manuscript over the the past year, I’ve immersed myself in the minutia of turn-of-the-millennium popular culture, developing strong opinions about Limp Bizkit and silver eyeshadow and butterfly hair clips and Ron Norsworthy video sets. I feel a bit territorial, like that entire era somehow belongs only to me.

But, of course, it doesn’t. Nevertheless, I was worried that Alex would get the era wrong, reducing it to its most worn-out signifiers — AIM, low rise jeans — or retreating lazily into one-note nostalgia. His book does neither. He populates his prose with descriptions of graphic t-shirts and defunct snack foods pulled from archive.org, a research process he told me took nearly a decade. He includes true-to-life period speech, peppered with the slurs, racism, and misogyny characteristic of the period. And then he introduces elements of horror. These aspects of the text prompted Simon and Schuster to print a content warning at the beginning of the novel, a fact which has featured prominently in its promotion.

On a sweltering August day, I called Alex from my apartment in Baltimore to talk band t-shirts, Josie and the Pussycats, the ambient violence of the late 1990s, and the advice Bret Easton Ellis gave him to lean into his novel’s provocations.

———

COLETTE SHADE: Hi, how are you?

ALEX KAZEMI: It’s so exciting to talk to you. It’s just so cool, the parallels between our worlds right now, and the fact that our astrological charts are so similar. I’m sorry that you’re also a Cancer.

SHADE: When’s your birthday?

KAZEMI: June 22nd.

SHADE: That’s so close. Mine’s June 27th. What year were you born?

KAZEMI: ’94.

SHADE: I’m older. I was born in 1988.

KAZEMI: But that’s a good time to be born. You had a lot of good moments with certain eras in life.

SHADE: Even those six years are different. I remember this prime era before 9/11, but after the fall of the Soviet Union and after the introduction of the consumer internet, those last few late ’90s years that you and I write about.

KAZEMI: Wait, how old were you when John Tucker Must Die came out?

SHADE: That’s not a touchstone for me, so I think that answers the question. I touch on American Pie. But I’m not really focused on teen movies as much as content produced by MTV, music videos, pop culture documentaries by MTV and VH1. For me, I have this periodization, these touch points. There’s ’91, which kind of set the stage with the fall of the Soviet Union and created this end of history optimism. And then you had the tech bubble, which is when your book takes place, [then] 9/11. And then in 2003, you had the Iraq War. And then 2008 was when it all popped.

KAZEMI: So are you asking me what kind of American cultural touchstone sort of brought out the inspiration for the book, or why I wanted to choose this period?

SHADE: I have a bunch of questions, and that was one of them.

KAZEMI: Well, Columbine was a big influence for why I decided to write about this period and write about American culture at the time, because I feel like it was sort of the ultimate symbol of the juxtaposition of what was happening with the tropes of teen culture at the time. We had Britney doing the “Baby One More Time” video, which was taking place in the high school, and then we had this huge tragedy of violence, also taking place in a high school, that was about these kids who felt disenfranchised by the anti-culture that was pushed to them by MTV and by the tropes of American culture, football players, cheerleaders. But also, it was the Tumblr era, and watching in real time as these teenagers in 2012 and 2013 obsessed over wanting to be teenagers in the ’90s. And I was like, “Well, I’m going to go investigate this now. What was it really like?” But I have a question for you as a reader.

SHADE: Yeah?

KAZEMI: Was there a point when you reading that you started to realize that I was sort of responding to or parodying the extreme teen genre, like Bully and Gummo and Spring Breakers?

SHADE: I thought that I picked up on that pretty early on. When they’re at the summer camp, the level of saturation was just so absurd. It’s a bit disconcerting for the reader, and that struck me as deliberate.

KAZEMI: Yes, exactly. It was a red herring. It was a bit of a trick. It was sort of to make you think that you’re getting into a novel that’s going to make you feel all the feelings millennials associate with watching She’s All That sick in bed with bone broth. I wanted to give that to people on a platter and then really make it really horrifying and—

SHADE: You wanted to do a bait and switch on people?

KAZEMI: Yeah, yeah, exactly. I mean, do you remember seeing suburban violence or hearing about it back then? Do you have memories of the way that boys were in that hyper-real animated Howard Stern-driven testosterone culture?

SHADE: I do, and I write about it. I think that there were a lot of really violent undercurrents in the ’90s, even though it’s seen as this period of peace and there were no major US ground wars. The Sopranos did a really good job picking up on that, as did a lot of rap music in the bling era. But it wasn’t until a few years later when we invaded Iraq that the violence really came out in the open, with the torture revelations and mainstream pundits celebrating really degrading forms of violence. We were all degraded by the violence that our country was perpetrating.

KAZEMI: A lot of things were brewing. When we look back, we forget all of those things, because for some fucked-up reason, we truly want to think it was just N*SYNC and Britney and Smile and TRL. And even that is very grim, if you re-watch it.

SHADE: Very grim. My husband [the author Lyle Jeremy Rubin] grew up in this idyllic suburban experience in Connecticut. He was born in 1982, just like the boys in your book. He had some really negative experiences in boy culture and then ended up joining the Marines. So he bridged the gap from the violence of boy culture to the violence of American foreign policy.

KAZEMI: Yeah, he’s our metaphor.

SHADE: So tell me about your research process. There’s a lot of period-specific detail, and you’ve told me that you spent years pouring over old Delia’s catalogs and things like that.

KAZEMI: It’s very traumatic, honestly. Okay. Basically every little detail required hours of fact-checking to make sure that they were popular enough to reference in the book. Something like a sour Jolly Rancher lollipop. I would have to go to the library, find an old message board of someone who went to a rave that night in 1999 or 2000 in the month I’m writing about and see them talk about the candies, the outfits they were wearing. I had to just go through eBay videotapes, home videos, YouTube compilations, archive.org, of course, MTV, things like that, the comedy specials. It was truly endless, and that’s why it sort of took so long. But also I think it took so long because when I got the book deal I was 18. You’re a different writer at 18 than you are at 29. So I wanted to just grow and take time and let the world and my 20s happen. That’s why there’s so many existential adolescent things in the dialogue, which are also a sort of parody of the type of talking that became normalized on TV at the time with Dawson’s Creek. I also tried to really go to bat to show that there were still a billion different subcultures people totally identified with. Whereas now, with Zoomers, they can see a clip of a Gregg Araki movie on TikTok and have no cultural reference of understanding what it is and still screenshot it and go buy Rose McGowan’s outfit. I was trying to show that the reason the characters are so pop culture-driven is because they’re building camaraderie off the arena of pop culture, which is gone. There is no more pop culture, I don’t believe.

SHADE: I mean, this was really the last era of mass pop culture before everything got super fractured.

KAZEMI: And that’s why I fought so much with my editors because they’re like, “Why are there so many fucking band t-shirts?” I’m like, “Listen, this is what I’m trying to explain to the reader, that this is the way of IRL expression.” It wasn’t the time yet of the social media culture where you go to a party in an outfit so you can monetize and create a currency out of that outfit by posting it to TikTok and getting likes. What I was trying to say was, “No, this is their way of trying to express their identity offline.”

SHADE: I think that this is part of why it’s so beloved by younger people.

KAZEMI: Exactly, because they know that that time represents a level of order they don’t feel like they can have right now because of the amount of notifications and inundation and just the sense of unrest that living in the 2020s gives you.

SHADE: This is kind of the thesis, or a sub-thesis, of Y2K, my book. In 1997, when the consumer internet and AOL really started to take off, and also the tech bubble started to inflate, it created this idea that everyone could be rich and there was this new frontier and we would transcend these old historical conflicts. It was a techno-capitalist utopia.

KAZEMI: You know what really illustrates that well? Josie and the Pussycats. That completely presents the level of order and obedience. Think about it: you find a band, you have the power of MTV and magazines. Teenagers are hooked on one arena. You can break out, have your song play right after N*SYNC. People are going to be like, “What’s this?” They had a utopian lab rat experiment with teenagers at the time. This was the peak of consumerist teen culture. And I thought about that a lot, and I thought about how bands like Tool and artists like Marilyn Manson were operating as a sort of space for people to feel a sense of understanding or hope by representing anti-culture. But like Brad talks about in the book, is the anti-culture just another byproduct of that same capitalism that the pop girls are peddling?

SHADE: Well, and it’s funny you mentioned that because that exact question is posed in [the 2001 Douglass Rushkoff-directed documentary] Merchants of Cool. He’s talking about Eminem and Limp Bizkit and Insane Clown Posse and Marilyn Manson and all of these quasi-countercultural, specifically male-dominated bands and aesthetics, but it was all going through the same channels.

KAZEMI: It was extremely heartbreaking for me going through the anti-culture stuff and watching disenfranchised kids talking about loving these type of bands and seeing that there was a level of exploitation going around, from the corporations and from the artists, that a traumatized young girl gets into satanism and Manson and all that type of stuff. There’s no level of healing there. There’s just a sense of rumination and obsession, and the corporations, stores like Hot Topic, they all monetize off of people’s pain and trauma. I was like, “This is fucking grim. This is gross.” What I’ve kind of realized is that when they have their bedrooms with pictures torn out from magazines, and they’re obsessed with PlayStation, they’re trying to cope with reality. They’re trying to cope with the nothingness of being alive.

SHADE: So Garth Greenwell has this essay in The Yale Review where he talks about the challenges of writing fiction and creating fictional narratives right now. He says, “The moral and political demands currently placed on art, the charge that art has, the responsibilities and consequences as grave as actions in the world beyond the frame, the conflation of art and activism, don’t just mistake the nature of art and art making. They make it impossible for art to do the moral work proper to it.” He’s talking in part about the present readerly environment, and viewer environment for film, where representation of really horrifying things is seen as endorsement. And I know that that has come up with New Millennium Boyz.

KAZEMI: With the content warning. Yeah.

SHADE: So let’s talk about that.

KAZEMI: You’re such a Cancer in your segue into this. Okay, so when I got the call about the content warning, the first person that I showed it to was Bret Easton Ellis, the author, and also my friend for many years. And I was like, “What do I do?” He’s like, “Trust me, this is good. Leave it. This is going to be something good. If your book’s getting stocked in stores, don’t try to fuck with that. Just trust it.” I found it fascinating that, in this post-Dennis Cooper society, post-Chuck Palahniuk, post-Ryan Murphy and American Horror Story, I kind of thought that I had the creative freedom to explore these topics, to satirize, to be more absurd because of that. But no. Particularly with this book, the sales rep said that they were afraid that teenagers would try to reenact the behavior, which was insane because there’s no sense of glamorization about any of it. I’m actually exposing it and reprimanding it. So I thought that was really weird, but I do think that we have to have these conversations. We have to deal with these issues. We have to show them it shouldn’t be edgy. The young women at the publisher were very upset when I had Cassie Bernall’s name in the text, the Columbine victim. But I was trying to make a commentary on this aspect of American culture where we have a parasocial relationship with the victims of things. We think, “Oh, I’m a savior.” I was trying to paint Brad’s moral delusions. So it just says, “Ca—.”

SHADE: That’s interesting. And I think that that says a lot about contemporary understandings of how a person should engage with a text. I’ve had discussions with people about Sex and the City, for example, which is very different, but there are things in the original show that people have said, “Hey, this isn’t right,” or, “This doesn’t jibe with contemporary notions of morality, and so I’m not going to watch the show.”

KAZEMI: It’s very strange, right? I think that’s also a bit of a Netflix-driven anesthetizing feel-good content that is being churned out by corporations. I was trying to show that this suffocation and claustrophobia of being online is actually a very violent experience, so that’s why I tried to portray that in my prose. Shane was a very big project for me because I studied the way that teenage boys back then would talk about depression. I read William Pollack. I read a lot of off-kilter books about adolescent psychology at the time, and a lot of the boys do struggle. They’re misguided in our culture, and a part of feminism should be discussing those issues as well.

SHADE: That’s also something that people are trying to get at today. There was that recent article on “male loneliness.” I saw it trending, and I was like, “Well, I have to turn in the next round of revisions on my book. I’ll get back to this later.”

KAZEMI: Oh my God, the editing and fact-checking process, my heart for you.

SHADE: I’m actually looking forward to that. I’m looking forward to rote stuff.

KAZEMI: For sure. I wanted to put a soundtrack at the end of every song that was mentioned, and then my publisher said, “Oh, no. Why wouldn’t we just make a Spotify playlist?” I’m like, “No. What would be fun is that they go and make the playlist themselves after reading it.” And they’re like, “No, no one’s going to do that.” I was like, “Fuck.” Millennials.