OWNER

Eli Zabar and Flynn McGarry Think Running An NYC Restaurant Is Worth the Pain

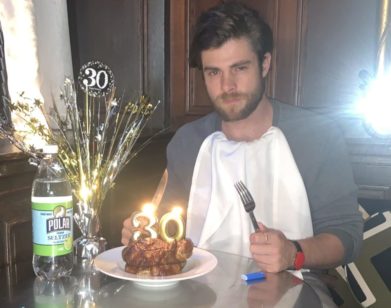

Photo by David Gruber.

Fifty years ago, Eli Zabar opened E.A.T. on Madison Avenue, reshaping how New Yorkers approached food shopping and dining with his emphasis on artisanal ingredients, elevated prepared foods, and the concept of gourmet takeout. Known for its impeccable salads, crusty breads, and a no-nonsense devotion to quality, E.A.T. has become an Upper East Side institution. Since then, Zabar has built an uptown empire that includes multiple markets, cafes, and restaurants, each reflecting his meticulous standards. To mark the milestone, Flynn McGarry, the 26-year-old wunderkind chef behind Gem and Gem Home, traveled uptown to E.A.T. to sit down with the legendary gourmand for a multi-generational discussion about the scrappy origins of E.A.T., the allure of the East Side, and the eternal quest for reinvention.

———

MCGARRY: When did you know what you wanted to do?

ZABAR: When I came back to New York [from London], I finally knew what I wanted to do at 30 years old. I wanted to be on Madison Avenue. I liked the way the women smelled with their perfume, and how pretty they were. I never wanted anything to do with the West Side.

MCGARRY: How often do you go back to the West Side?

ZABAR: Not often. I see my brothers every few weeks.

MCGARRY: But you wanted to be on the East Side?

ZABAR: I had to be on Madison Avenue. I looked and looked. I had worked in construction and wanted to be a developer. I was hooked up with a guy from high school whose family was in real estate. I ended up taking a job at Pete Morel’s wine store for $200 a week, six days a week, open to close. I’d do everything, while looking for my own place. The moment I got it, that would be it. I did that for about six months while looking for a location south of 79th Street. North of 79th was still very sleepy and family-oriented back then. They had theaters, drug stores, a bar or two. Next door to this store was a run-down deli with some old guy. A funeral parlor was on the next block, which never encourages business. You were stuck here with the worst things—the funeral parlor, PS6 public school across the street, banks.

MCGARRY: Yeah, you had the trifecta.

ZABAR: We had the trifecta, but this was all I could afford. A big, fat guy in the art gallery business was going out of business. The only asset he had was a leaking air conditioner over the front door. I made a deal with the landlord to rent this space starting in the fall, but the guy said if I paid the rent, he’d get out now. In my previous job, I was the office boy for a developer. I went to get coffee, but was supposed to be the assistant project manager. I made friends at the job sites and met some real carpenters. I went to the store, got three guys I was working with, and we did the demolition and carpentry ourselves.

MCGARRY: It’s good you mention the jobs you kind of failed out of, because you ended up doing all of them, you know? Having a restaurant, grocery store, being in real estate, construction, having the wine store—it’s a way to create every job you ever wanted in one space. When you first opened the original space [E.A.T. Gourmet Food Shop and Cafe], did you know you wanted to expand into all these other areas?

ZABAR: When I got that store, I was working at an even smaller store across the street, about three or four times the size of this room. I wanted it really small so I could do everything myself and never work for anyone again. My only goal was to make as much as I did as a teacher, which I had been doing for a year to dodge the draft. When things started getting popular and people suggested expanding, I would say all I wanted was to be–

MCGARRY: How long was it just the one thing?

ZABAR: About four years, until I got approached by Henri Bendel’s department store. It was the Barneys of its time. How old are you?

MCGARRY: I’m 26.

ZABAR: This was well before you. Geraldine Stutz, who owned the store, wanted a food department. Somehow she had heard about me. She had all kinds of crazy ideas about what you could do there. She offered me a spot on the main floor about the size of this right here. So we have this store, and my first idea—before opening, I put a manifesto on the window about what I was going to do. I wanted to find people who made things the old way—bread, jams, prepared foods, salads. I was going to do cheese and smoked fish since I knew about that from being an assistant buyer. Everything else I was going to purchase. That’s how it all began. But none of that worked out because there wasn’t anyone doing it or they were too expensive. So I ended up learning how to do it all myself.

MCGARRY: I think that’s a key point. It all comes down to, “I have to do it myself.” It’s so hard in New York. If you want anything good, you have to make it or find it yourself. You’re like an importer, you import wine—

ZABAR: You really can’t import easily. I wanted the unpasteurized cheeses, crème fraîche, big blocks of cheese that I had in France, and different kinds of figs. Back then, before the internet and fax, communication was hard. But I put in a huge typewriter-like thing and managed to find some contacts and I started to import cheeses myself. Because if you want something–

MCGARRY: You’ve got to get it.

ZABAR: Exactly.

MCGARRY: The expansion comes from wanting to do cheese, make bread—now you need an oven, people. It grows like that every time you want something.

ZABAR: Yes, we had a little oven here at first. I got in a fight with a French Bakery. I was buying croissants from a good French Bakery and then I figured out how to do it myself and said “Fuck you.” Once you have the oven, you can start making something else. It becomes impossible to create a moment exactly like that place in London or Paris. You start off wanting to do it the same, but you can’t.

MCGARRY: But you have the reference.

ZABAR: You have the reference, then end up doing it your own way, and your own way ends up being somewhat interesting. I wanted to learn to make cakes like in a book I bought, but mine was lopsided. I don’t have the piping skills, but you discover things that—

MCGARRY: It becomes your style versus an amalgamation. So many businesses open now with a pastry chef from here, a person from there. There isn’t that process of figuring out how you want to do it.

ZABAR: But that’s really the process, trying to figure it out.

MCGARRY: You create your style versus this amalgamation. If you don’t have the budget to hire a pastry chef, maybe it’s not right anyway.

ZABAR: Where you don’t have money, you don’t have the money.

MCGARRY: I read in a Tina Brown book, The Vanity Fair Diaries, she would tell her team “If you don’t have a budget, get a point of view.” I see that so much in restaurants. Sometimes the budget ruins the project because you don’t need to get a point of view. You can just open the exact thing you want, bring everything in, versus being scrappy. As you got more funding for larger projects over the years, do you think you still brought that scrappy approach?

ZABAR: Absolutely. I always used whatever I made to expand on my idea. I kept enough to live on, then expanded thoughts and ideas or bought another piece of equipment.

MCGARRY: I think that takes so much conviction and a dumb confidence to buy the thing because you want it and you’ll figure out how to make it work. Do you think there’s a moment where you’re like, “Now we’ve gotten to the place where all these investments paid off”? Or is it forever—

ZABAR: It’s forever. There’s never enough money. So many things I would buy, purchase, or do if I had funding.

MCGARRY: It’s always about buying the next piece of equipment. It’s such a funny thing with restaurants. It’s equipment, it’s people. I want to make this new thing, we need two more fridges. Then we have the fridges, now we need to pay for them. It’s always this cat-and-mouse game.

ZABAR: Yeah, it keeps going and going.

MCGARRY: When was the last time you built a new project?

ZABAR: Well, this [E.A.T.] is a total renovation. Over a million dollars. I don’t believe in closing, so we moved the retail into this side, built the retail, then moved back to that side. We were always open. I’d say that’s the last big thing we finished in the spring, before summer or fall, I can’t remember.

MCGARRY: Even redoing such a big project is almost harder than getting a blank space and just doing it. Did you always have this side too?

ZABAR: I started in ’73 there and got this in ’86.

MCGARRY: Okay.

ZABAR: When I got this, there was a bookstore here. I didn’t really want this space. I wanted something small. But I was baking in the cellar of that building in a space not really as big as this. We’d completely outgrown it. All I wanted was the cellar on this side, but to get it, I had to take the—I had no idea what to do with it. By luck, we discovered that around 1900, there used to be a caterer or bakery here with a coal-fired brick oven in the backyard. I mean, things happen.

MCGARRY: That’s crazy. How did you go from serving and selling food to having a sit-down restaurant? Was that interesting to you?

ZABAR: No. I always had, and still have, a fairly low opinion of people in the restaurant business. Maybe now that I’m in it a bit, I should change my opinion. [Laughs] But I always told everybody we were in the business of takeout cold food. I thought, if you’re making something hot, it should be good. Why shouldn’t it be good? Getting it from the stove to the table is the challenge, but if you’re making delicious things, why shouldn’t it be good hot? I didn’t think there was much skill on that side. We ended up with this space by accident because I wanted the basement. You deliberately went into the restaurant business as a kid.

MCGARRY: Yeah, the wrong side of it. I found myself on the other side.

ZABAR: Right.

MCGARRY: I’ve always been obsessed. Growing up, most of our food came from a nice deli. I think New York is in a new renaissance of realizing that. Everything’s always been bigger up here, but downtown, you sort of freak out at the idea of going to a place nearby, getting some nice vegetables and pre-made things that were made well. “I don’t have to cook this whole thing,” which was my mother’s philosophy on food. “If I go to a nice grocery store, buy a nice tomato, olive oil, and grilled artichokes, I can have a delicious meal without having to cook for my kids.” You’re essentially ahead of the game in really pushing this as the easiest way to get your product to a customer. When you say you’re not in the restaurant industry but have restaurant projects, are they worth it? You’re adding all this service, overhead and stuff compared to just saying, “Take what we’re making and take it home.” Do you think they need to coexist, now that you have them?

ZABAR: Well, first, here we’re just serving what I make. The salads are 90 percent of the menu, and some soups. It’s a very limited hot menu, almost not there. That’s all I was capable of doing myself, not much more. But when I did the market, I always envisioned a restaurant in it. That’s the only restaurant I really have. I have somebody who does the cooking and I like their very simple touch. I have a big input into what’s on the menu. In fact, I decide what’s on the menu.

MCGARRY: I assumed so. I see you from the outside as a curator of all these things. But one of the hardest, most frustrating things for me, looking at restaurants and groceries as curation, is that you end up being the manager of managers and employees.

ZABAR: That’s why nothing’s ever right around here. [Laughs]

MCGARRY: Are there ways you’ve seen success in getting people inspired to do it right? Or do you think it’s in their nature. You can’t teach someone who comes in from any other organization to care about the things you care about. It’s either they come in and care, like you said, this chef doesn’t have a lot of experience but he cares—

ZABAR: It’s the latter.

MCGARRY: Yeah.

ZABAR: It’s extremely disappointing to say this after 50 years in business, but the person’s got to come to you with it inherently. What’s your experience?

MCGARRY: From top to bottom. The frustrating thing about the industry is that there just aren’t many people who get it. Especially now, what’s really disappointing is the ones that do get it, have the vision, get that perfect thing and 90 percent of the time the ones that don’t want to work. They know they have it and can get more money anywhere else. We do it all the time, trying to keep someone in that perfect place who gets it but isn’t like “I deserve everything.” I wonder if that’s very American, the way you and I both want to be our own bosses. My therapist always says, when I complain about my employees for hours, “If they could do it like you, they would be you.” You can’t expect everyone to have that same vision. This is how you see chefs burn out. So it’s quite refreshing to hear you be like, “Things are going to be wrong.” And it doesn’t get better, it sounds like.

ZABAR: It doesn’t. Sometimes you get lucky and you find some people who are really good and really do it. That’s great, you honor and appreciate them.

MCGARRY: In this never-endingness of it, did you ever have a moment of being like, “Maybe this isn’t worth it anymore?”

ZABAR: I feel that a lot.

MCGARRY: Is there a thing you go through that brings you back to it? Like “No, it is worth it.” Or is the thing that’s worth it, “Well, I can buy this new piece of equipment and maybe it’ll all get better”?

ZABAR: I think it’s a lot of the latter.

MCGARRY: You have to have optimism.

ZABAR: It depends how tired you are, too. Fatigue is a good part of the negative feelings. Saying something incredibly stupid while fatigued is a very bad combination.

MCGARRY: Yes. But you were always happy having the one small store. You never wanted to grow it into a big empire. You had the one store, wanted to make what you wanted, charge what you wanted, and be excited every day coming in.

ZABAR: Right. That works.

MCGARRY: There was just that necessity of having to do more, so you had to purchase big ovens, get a new space, add another space.

ZABAR: Well, I think there’s the element of getting out of the depression you have at the moment and saying “Hey, that something is really good. I’d like more people to have it.”

MCGARRY: You never know when it’s all going to work out. It’s funny, I’ve had so many conversations with older chefs and it’s always that thing of, “I was happiest with the one thing.” One of the chefs I used to work for and see a lot as a mentor is Daniel Humm at Eleven Madison Park.

ZABAR: Yeah, I know him.

MCGARRY: I remember talking to him about opening another restaurant. And he was like, “Don’t do it. I had 10 things and I closed all of them. I have never been happier my entire life.” There’s that funny balance. It’s a city that always wants you to do more.

ZABAR: Yeah, it is the city. But you have the population. If you were somewhere else with one place, you’d be lucky to have it.

MCGARRY: It’s almost the ability to be able to do it. It’s that fact where you say, “I can open the thing here, people are going to come.” The fact that you can do anything. I wonder if there’s something not bad about it, but where it tricks the reason why you’re doing it. Are you actually doing it because you want to do it, you want to be in the kitchen or sell the things you want? Or is it because you can do it?

ZABAR: Well, that’s a good point. We put a juice bar into the Grand Central Market I had, which seemed like a logical growth for me. They’re selling fruits and vegetables, or not selling them, so why don’t we do a juice bar? I had a guy working for me who was Korean, who ran a Korean one. I thought, “Okay, this guy makes all the smoothies, he has more passion.” Then you have the guy with the know-how and he makes really fresh juice. So we tried to lease another space to do a store. I said to Oliver, “Why don’t we put a juice bar?” And Oliver says, “Forget that idea. I’m always right, you make it more complicated.” You know, every great author had a great editor. That’s kind of what’s missing in me, I don’t listen to anybody.