The Outsider

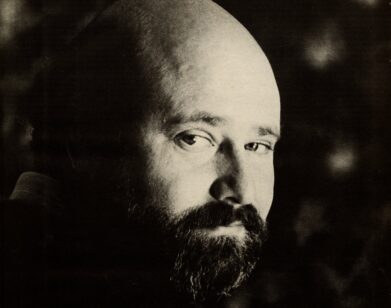

ABOVE: YANN DEMANGE ON THE SET OF ’71. PHOTO COURTESY OF DEAN ROGERS/ROADSIDE ATTRACTIONS.

Set in Belfast during the height of The Troubles, ’71 presents a city divided. The conflict, however, isn’t limited to the usual Republicans versus Protestants, English versus the IRA, colonizers versus rebels. Every group is fragmented and, in some way, at fault. Older Republicans make backdoor deals with British spies to assassinate their younger rivals, and British spies lie to the British army commanders. Within the army, the accents of officers and lieutenants—posh, private school boys who sound like they’ve swallowed a jar of treacle—are so comically different to the men they are supposed to command that they are instantly segregated. And it continues. At one point, an Irish woman tells the protagonist, British private Gary Hook, that she has relatives living in England. Hook is from Derby; her relatives, she tells him, live in Lancashire. “People from Derby don’t like people from Lancashire,” he replies.

Most of the film’s action takes place over a 24-hour period when Private Hook, played by the phenomenal Jack O’Connell, is separated from the rest of his platoon. The first feature film from director Yann Demange, it is tense, violent, and emotionally consuming. Born in France, raised in West London, and half-Algerian, Demange seems like an unusual choice for a film about Northern Ireland. Within the first half hour, however, he convinces you otherwise.

EMMA BROWN: What made you want to tell this story?

YANN DEMANGE: It was the strength of the screenplay. I had no desire to make a film about Northern Ireland, the screenplay fell in my lap and it immediately resonated with me on a very personal level. It’s got themes in it that I’d been trying to put into my work, in a screenplay that I’d written that I didn’t feel was strong enough to try and get made [and] that was set in Algeria. As soon as I read it, it just felt incredibly contemporary. It’s sad to say. I could identify a pattern I can see playing out right now in Iraq, Afghanistan, Ukraine. I really connected emotionally with telling this story about kids caught in conflict.

BROWN: Were you living in London when the IRA was still active?

DEMANGE: Yeah. I was born in Paris, but by ’79 we were in London. I grew up in the landscape with all that going on, but I’m an outsider. We didn’t speak English at home; we spoke French. I’m not Anglo-Saxon and I’m not Celtic. It’s that insider-outsider thing. I’m a Londoner, but I don’t have a national identity. I’m a French passport holder raised in London and that was the white noise of my youth. I never quite understood what was going on. But you wouldn’t get the bus to school one day because there had been a bombing. You’d hear Thatcher on TV. But it was all spin. They never taught us at school what was going on, they were never really open about explaining it. Even now, my niece and nephew are 20 and 23, they’ve just gone through the schooling system in London and it’s still not on the curriculum. It’s almost as if it’s been erased from history.

BROWN: Jack O’Connell is having a great moment. Had you seen his previous film Starred Up? Or did you cast before Starred Up?

DEMANGE: I cast him before Starred Up. I moved my whole shoot to accommodate it. He’d got that, and they were ready to go because it was a much smaller film to prep. Film Four were involved in both films and talked. And when Jack told me about the story, I fully supported Starred Up—it’s the sort of film I’d like to make. I thought, “Okay, I’ll make this work. I don’t want to cast somebody else,” even though there was a pressure to. So what we did is they brought their shoot forward, and I pushed mine back so he could do both. And then for Unbroken, there was a request to see some rushes, so we did that. But I cast him before both those films. Strangely I’m reaping the rewards of both those films because I’m coming out after them. Which is wonderful. He’s a star; he’s a star in the making.

BROWN: Did you cast him based on the strength of an audition or was it from Skins?

DEMANGE: No. I’d never watched an episode of Skins, I don’t really watch that sort of stuff. No judgment. I know a lot of the writers involved in that show, but I don’t really watch much British shows like that. I’d seen him in Dominic Savage’s Dive. It’s a lot of improvisation; it’s about teenagers, a teenage couple. He’s wonderful in it. He’s also in This Is England—that’s where I actually first saw him. He was always on my radar. I was worried he was too old. I’d seen pictures from the sequel to 300, and he’d obviously been training and really got ripped for it. I was like, “God, we’ve missed the time. We’ve missed the opportunity.” But I met him and we had a couple of pints—he’s old school; he’s got that old school masculinity. Most actors his age, his generation, if I were to have a meeting with one in L.A., they’d have come straight from the gym and want to go to a juice bar. I met him and we had a couple of pints, talked about football—it was the middle of the day—and I just knew he was right for it. I knew he understood the character. He read one scene, which was the scene with his little brother. He did it three times: once just riffed on it, a cold reading, and twice with some notes. And I was like, “That’s it. This is my man.” He’s the only person that could play it. I couldn’t imagine making the film with anyone else.

BROWN: How’s the reaction in Ireland been?

DEMANGE: The reaction in Ireland has been the most moving and touching of the whole thing. In London, no one really went to see it. It’s seen as a success in the UK because of Ireland and Scotland. In Ireland they really came out to see it, which is kind of unheard of because they usually don’t bother to go see films about The Troubles. People on all sides came out to watch it. I met a lot of people when I was researching who were very active on all sides, and I had to go back and look them in the eye and go, “Look, this is what I’ve done with your stories.” I was very nervous—more nervous than any other screening in the whole process. A lot of women actually came to the screening and wanted to share their stories, because they felt—though there were not many female characters in the film—that we’d caught that feeling that they were on the frontlines too, trying to protect their men.

BROWN: There was that great scene where they the British soldiers walk down a street in Republican territory and all the women start drumming on the pavement.

DEMANGE: That was a detail I’d heard when I was researching and we put it into the film. Just meeting people, it kept adding details to the film and texture.

BROWN: Were people quite keen to talk to you?

DEMANGE: In the beginning, they were a little reticent. I suppose I was a bit fortunate because I did a TV show called Top Boy with Ronan Bennett, who was the screenwriter. It’s not a secret—it’s on Wikipedia—that he’d been in the Republican movement and had represented himself at the Old Bailey. He’s a bit of a legend. Because we were good friends and he had very good contacts, he reached out to a few people and I met people. I promised names would be kept out, but let’s just say I had an in with a lot of people that had been involved. The producers [also] need a big mention. Angus Lamont started the whole idea and his producing partner Robin Gutch had produced Hunger. So by virtue of having produced Hunger, which is, in my eyes, a masterpiece, and the people back in Ireland are very proud of that film, it came with a kind of validation and people would talk to us. That pedigree opened doors for us in many ways.

BROWN: When did you first become interested in film?

DEMANGE: Very young. But I don’t have one of those anecdotes abouot playing around with a Super 8 camera at eight years old or anything like that. My mum was a cleaner. My dad worked in bars. No one had a degree in my family—I was the first person to go to university—so it’s not like there was a role model. My mother just adored cinema, and also because she was an immigrant, she only spoke French, we had a VHS machine very early on. It was the poshest thing about our life. Still to this day—she’s 75 —she’s stubborn, she won’t move back to France but she still won’t learn English. So she used to get sent VHSs from France all the time, so I grew up watching all these Godard and Truffaut films, a lot of the old trashy [Jean-Paul] Belmondo films. I can’t pretend that I loved what I saw. I wasn’t some highbrow kid. It’s not like I was lapping up the New Wave, it’s just that I was there exposed to it. I’d keep recording over our French films with, like, Carpenter movies or horror films. But I grew up with a foot in both camps; a lot of it I found boring, but some of it is just part of my DNA now. I loved cinema, but there wasn’t a point where I ever thought it was a possibility. It was all pie-in-the sky shit. When I was 17 I got a phone call from someone I knew that said, “Look, have you got a passport?” I said “Yes, why?” And she went, “Someone let me down, there’s a music video with and we need someone to come over to Ibiza tomorrow.” I said yes and before you knew it I was an assistant on music videos and it demystified the whole thing I remember having this moment looking around going, “I’m not as educated as everyone else here, but I think I could have a crack at this.”

BROWN: Obviously there are a lot of downsides to being the perpetual outsider, but what are the good things about it?

DEMANGE: It’s a complete nightmare when you’re growing up. I guess I imposed that on Gary Hook’s character. Everyone wants to be part of a tribe. I still have those moments where it’s annoying to not have a tribe. But it’s also incredibly freeing and now, to be your own man. In terms of being a director, not to be partisan is a good position to be, and a good window into the world. But it’s also been, growing up, the source of a lot of pain and rejection.

BROWN: You mentioned that before ’71, you were developing a film about the Algerian Civil War in 1991, and now you’re working on a movie about the 1992 riots in L.A.

DEMANGE: Yeah. With the same writer and producer as ’71.

BROWN: Is it a coincidence that these three films are all about very intense points of conflict within a community?

DEMANGE: I think it is a coincidence. I started off doing dark comedy. I’ve got a dark comedy idea that I’m doing with Sony. The Battle of Algiers was a major influence in my life—my aunt is in the film. She plants a bomb in the milk bar. It’s always hovering over me, and I do feel, certainly with the L.A. riots, I want to make Battle of Algiers in L.A. It just feels pertinent to right now. I’m not going to do a trilogy, but it’s almost like a companion piece to ‘71. But in year’s time, I might be doing an oddball comedy set in space.

’71 COMES OUT IN LIMITED RELEASE TODAY, FEBRUARY 27.