CINEMA

Writer Ian Penman on Foucault,Freelancing, and the Films of Fassbinder

It was late 1976 or early 1977 when a teenage Ian Penman committed the crime that marked him out as a born magazine writer. It was after the Sex Pistols played the Chalet du Lac in Paris, but before the Red Army Faction killed that federal prosecutor in Karlsruhe; after Mao’s death, but before the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. It was, in other words, the historically right time for a schoolboy in small-town Northern England to risk expulsion by spray-painting “ANARCHY RULES” onto the school building’s bricks. Pithy, tongue-in-cheek, on-trend: the phrase was the kind of ironized double entendre (anarchists, of course, are opposed to ruling) that would have looked better on a newsstand. Penman was destined there. Forswearing art school, he moved to London on his nineteenth birthday to become the youngest star critic at the New Musical Express, or NME, writing speedy, heady missives from a world where seemingly everything that mattered was post-something, whether it was structuralism or punk.

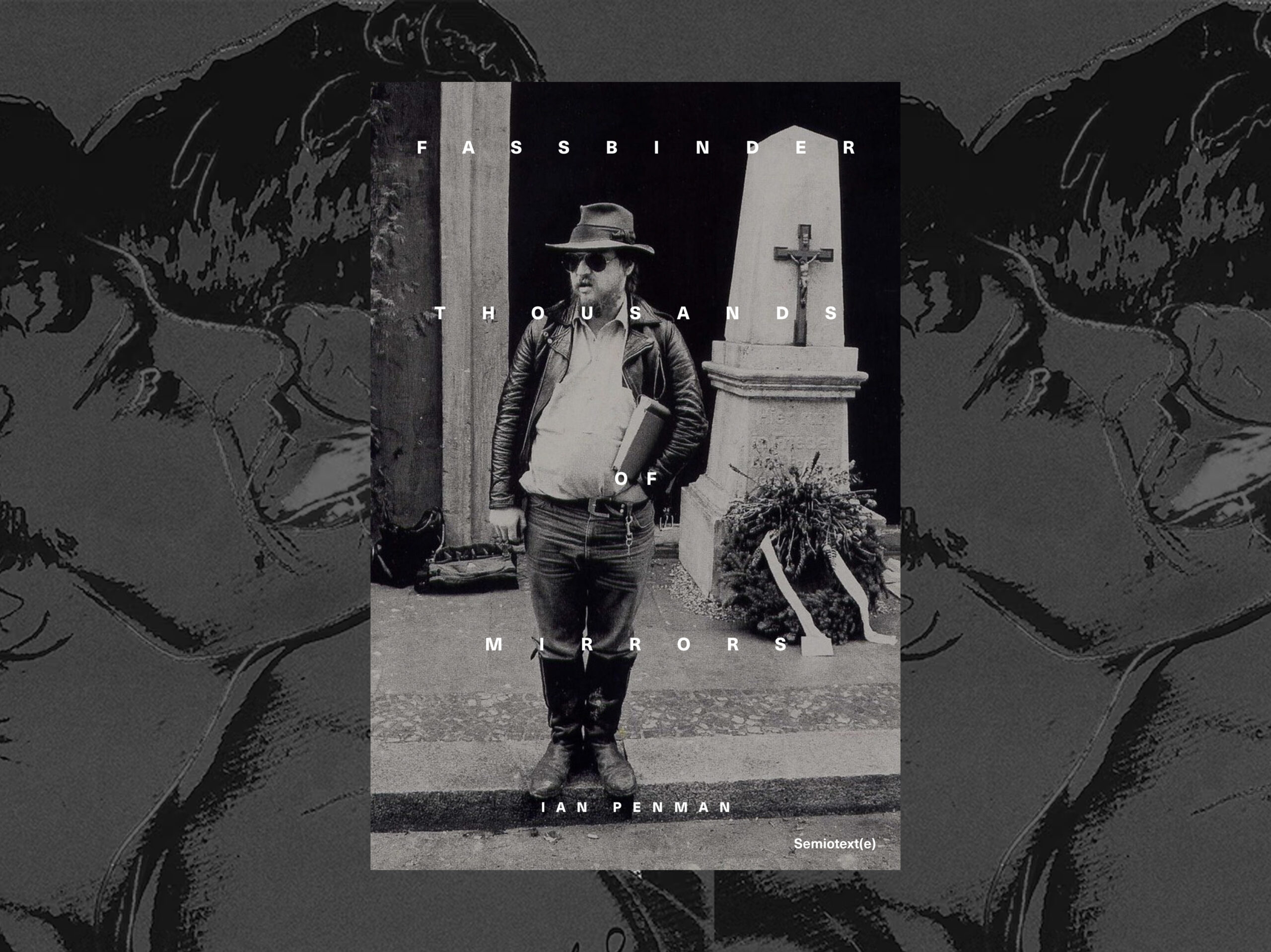

Penman’s role model in those days—a fellow effete autodidact, the artist he saw as a bigger rock star than any screaming guitarist, the filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder—is finally the subject of his first full-length book, Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors, out now from Semiotexte. Forty years of watching, four months of writing: that’s the book, composed from over four hundred odd-angled, lambent prose fragments. Penman, who now lives in Manchester and writes for the London Review of Books, is pale, apprehensive, and deeply thoughtful. He does not have a cell phone. His luggage: three tote bags. When he rings the doorbell to my apartment, it’s noon on the dot.

———

SARAH NICOLE PRICKETT: How do you take your coffee? Americano?

IAN PENMAN: Just a tiny bit of hot water. And if you’ve got some sugar—my last remaining addiction. So where are we, actually?

PRICKETT: Williamsburg.

PENMAN: Someone asked me before I left England, when was the last time I’d been to New York? I said oh, it wasn’t that long ago, it was 1990-something—and of course that’s 25 years ago, a quarter of a century. I tend to do that, to think it wasn’t very long ago when in fact decades and decades have passed. Everyone says how much New York City has changed.

PRICKETT: What’s the most noticeable change, to your eye?

PENMAN: The thing I have been noticing the most is one thing that hasn’t changed, which surprised me—the graffiti. It’s still here, on trains, on trucks, everything. I thought that era had gone. But my friend said that in the 1980s there was loads of graffiti, and now it’s back again, and I missed the in-between part.

PRICKETT: The Giuliani years.

PENMAN: Right, I wasn’t coming so much by then. And then after 9/11, I stopped flying. It wasn’t so much my safety as it was suddenly having to queue for hours and hours. I grew up flying, that’s the irony of it. I did it from a young age, back in the days—in the early 1960s—just before the period of cheap flights, cheap holidays in Spain and so on. When we flew, it was still kind of an exotic thing, especially being from a working-class background.

PRICKETT: Now it’s requisite, and they don’t let you smoke. Were you like Drew Barrymore, eleven years old in the airplane smoking wing?

PENMAN: Funny, no. I didn’t start smoking until I was in my thirties, and I didn’t quit until eighteen months ago, just before writing the book. I’m almost prouder of having quit than I am of having written it. My parents didn’t drink or smoke. I don’t know where I got my tendency toward rebellion from. Maybe my grandfather, who was apparently quite a black sheep.

PRICKETT: Maybe rebellion is like red hair, its gene is recessive. When you decided to write for NME in lieu of going to college, was that considered rebellious?

PENMAN: It was something in the air I think, just because of that punk moment, though by the time I started at NME it was a post-punk moment. People suddenly thought, “Well, I’ll just do something from scratch.” I was someone far more naturally into drawing and painting than writing.

PRICKETT: Your pieces for NME are infamously full of references to French theory. Do you feel that you read more, or more widely, because you were reading as a writer or a fan and not as a student?

PENMAN: I think there was a time when the autodidactic was dignified, when it was something to be. Especially in working-class culture, I think, where there was a slight distrust of the academy—with good reason, because it can take the best out of people, it can produce very desiccated texts. I do think it takes some of the fun out of it, to have to read Foucault in order to write about Foucault in the language of Foucault or in the language of other people who write about Foucault. When I was reading all this stuff, a lot of it was just newly translated into English and it was at the bookstores in Soho, and I was reading whatever it was, Bataille, Lacan, Foucault, with the radio or the record player or the television on, drinking a beer. I was having fun with these texts, is the point. My theory days were never about yearning for anything academic, it was about how you could pick up a text and turn it around and see how the light reflects off of it, if you write not just about a Beckett book but how does it look if you apply it to this, or put this color over here, against a piece of pop music or something. That hadn’t been done so much back then. Now it’s become more popular, and sort of a terrible problem.

PRICKETT: I would hate for you to see some of the juxtapositions I’ve forced onto the pages of fashion magazines.

PENMAN: A thriving magazine culture is a sign of a good culture. I owe everything to magazines. Without them, I wouldn’t exist. I would get up in the morning and write 900 words about something and it would be on newsstands in a month. It wasn’t meant to be read thirty years later. I wouldn’t want to read almost anything I wrote in the ‘70s and ’80s, but I do have this working-class pride about having learned on the job. There was a generation of filmmakers coming up, like [Wim] Wenders and [Werner] Herzog, who were roughly the same age. I think they were all kind of eyeing each other and a bit competitive, but I don’t think they interacted much. Though I remember reading an interview with Herzog where he sounded heartbroken and almost angry about Fassbinder’s death, you know, saying he had so much left to do.

PRICKETT: Do you think he knew he’d die young?

PENMAN: I think toward the end, yeah. If you read interviews with him, you can see it. Like in the interview he gave about Cocaine, he says something like, “It’s not really about cocaine, it’s about a man who takes a decision to live a short life and live it very intensely.”

PRICKETT: It’s funny that the one movie he didn’t do was Cocaine. Premonitions of one’s own death could also just be moments of honesty about how [one is] living. I mean, if you’re making two films a year, doing drugs every day…

PENMAN: Yes, although it was only later on, from around the time of Chinese Roulette, that the cocaine usage really took off. He was working at that speed for years and years without doing an unusual amount of drugs. It’s just astonishing. My admiration for him, just from that angle, that respect, has only increased with time. So yeah, it would be too easy to stress the monster drug addict aspect too much.

PRICKETT: What I meant was more so, was he self-destructive or was he somehow predestined to die? I’ve thought before about artists who are prodigious in their output, who seem to know they have less time than others in which to do more. I’ve thought this about Proust, though in his case I suppose he was always sick, and Peter Hujar. I wish I could think of someone who wasn’t a gay man. Sarah Kane? No, she’s a gay man too.

PENMAN: I don’t know if he knew early, early on, but there were those three years during which he did go completely over the top, in which he may have decided to enact a slow suicide, a sort of suicide in installments. But, as I say in the book, if you look at photographs of him in those remaining three years, he’s never looked happier. There are photos of him on the set of Querelle where he looks like a boy who’s got the thing he most wanted for Christmas.

PRICKETT: Maybe he’d let go of some affectations, or some idea about how an “auteur” was supposed to look.

PENMAN: Yet at the same time, Querelle is his most auteurist film. It’s like a film based on his filmography, images of images. The style is so total, eclipsing what there is of a story, almost as if he is saying there’s no story left to tell.

PRICKETT: I watched Veronika [Voss] and then Lola last night, which is apparently wrong even though Veronika was made after Lola.

PENMAN: Yes, he made them out of order. Veronika Voss is beautiful, possibly my favorite of his films, but I find it hard to watch now because of what we’re talking about—the helplessness of addiction, the sense of being predestined to die. It’s such a sad film in that sense. Lola is one of the only films where there’s a kind of happy ending, albeit hedged around with many reservations. Lola, to me, is the last of his films in which the psychology of the story merits the extremity of the style. Fassbinder’s lighting and color were hugely influential on so many directors, like Michael Mann, which I talk about in the book.

PRICKETT: He loves to have a light flashing for no significant or discernible reason. You know, there’s a scene in Fox & His Friends, where they’re sitting in a sitting room and behind them is another room in which a lamp-like light rhythmically switches on and off, but the source of the light is unseen. Or similarly there’s a scene, I think in Veronika, where again some off-screen light source seems to be rotating like the moon, light, dark, light, dark.

PENMAN: Whatever it is, it’s psychological. The problem with the Michael Mann thing of using that [lighting] is that it’s like Fassbinder without the psychology, so it’s just these really beautifully lit criminals.

PRICKETT: I guess I don’t really see the problem. I like criminals. They keep psychology in business.

PENMAN: Or even Scorsese. The difference between Fassbinder and Mann is that Fassbinder has women in his films, whereas Mann has ciphers in the shapes of women. Mann’s women are only there to italicize the men.

PRICKETT: Fassbinder’s women being the void in your book—is this something you said, or someone else?

PENMAN: It’s what was suggested to me, but I think it’s true. I think someone else should write that book. Gary [Indiana] says that the secret to Fassbinder is that he really wants to be a woman.

PRICKETT: Of course. Only as a woman could he be punished to the extent that he craves, that he feels he deserves.

PENMAN: Do you think he’s a misogynist?

PRICKETT: Sure, maybe. He’s a really rare and, to me, relatable kind of misogynist. Him and Lars Von Trier, these kinds of directors that I categorically forgive for being men. What I would say is that he and Von Trier both identify with women, which is not at all the same as identifying as.

PENMAN: Fassbinder said shades of that in interviews, that his emotional life was more like the life of a woman than that of a man. I think the other thing to remember is that watching Fassbinder’s films, especially in the middle period, in the 1970s, the women—and the men, but especially the women—there isn’t a type and they don’t look like people who were in Hollywood movies at the time. He cast people for their differences rather than their sameness.

PRICKETT: There’s a specific, slightly coarse appeal that almost all his female leads share. Something about the nose and chin being slightly over-pronounced, the plane of the cheek a bit roughly chiseled. Faces with almost too many angles.

PENMAN: You could start with Fassbinder’s own face as a template. In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, when he was still acting [in his films], you would see his face on screen and go, “Wow.” It’s not that he’s good-looking or handsome in any conventional sense, because he isn’t those things. But he’s so striking. It’s a face you can’t take your eyes from. His mother has that face as well, I think. Maybe that’s where it all began.

PRICKETT: I think you say something like that, perhaps that exact thing, in the book.

PENMAN: [Laughs] Does it all begin with the mother’s face? That’s right. Odd relationship, obviously very intense. I don’t know if you’ve seen the scene in Germany in Autumn where they’re arguing about politics. She’s very dignified. She can give as good as she gets. Her job in those days was translating American literature into German. Very cultured, semi-bohemian existence. It’s nice, actually, the timing of the book. It wasn’t planned, but the book’s come out at a time when all these films are available to be seen on Criterion and so on. A lot of them you couldn’t see at all for years. And so it’s nice that they’re there now.

PRICKETT: In the book, you write about different times when you didn’t write the book, and about wanting the book to retain some essence of those earlier times.

PENMAN: Yeah, there’s a tension there in the book between that young me in the ‘80s who thought Fassbinder was great, who thought that his fatalism was the truth, and the older me who thinks that he had a quite adolescent male view of the world. “Adults are awful, everyone’s a hypocrite,” this rock-and-roll teenage point of view. But if you survive that and you grow into middle age, it does become a problem. Eventually you think, “Is this really a true picture of the world?” Because he didn’t grow up, and you wonder if he had grown up, would he have repeated this same picture endlessly? These films say there’s no love, there’s no chance of self-knowledge or liberation or finding love, and it’s a very lopsided view of things. Everything I say is wrong with [Fassbinder’s ethos], that it’s too partial or too dark or too claustrophobic or too artificial, that’s all true of the book as well, deliberately so. It’s a mirror. What I leave out of that partial picture is that it was also enormous fun in that post-punk moment. To produce a more Fassbinder-y book, I had to obscure the parts of my experience that didn’t fit in the frame.

There’s an ambiguity to Fassbinder when it comes to this stuff. He criticized capitalism in all his films and was quite left-wing. He also loved being paid in cash, in these enormous sums of cash which he demanded from his producers and so on, loved buying sports cars for his lovers like the one Lola has, loved buying drugs obviously, there’s more and more profligate spending as the years roll by, so the tension is there and it’s mounting. But the other interesting thing about this segment [with his mother] in Germany in Autumn is its shot in his apartment, which is so horrible, it’s so claustrophobic and it’s all in shades of brown, tobacco, nicotine, and there’s no pictures on the wall, there’s no relief. You get a sense of this person prowling in his cage. You think—a person with this great visual sense, how come he’s living in this muddy, awful flat?

PRICKETT: That was what he thought real life looked like.

PENMAN: Yes, nothing to return to. So the minute you finish one movie, it’s on to the next so you don’t have to live life at home, you can live entirely on set or in camera, as it were, because real life has consequences and repercussions and limits and he didn’t recognize any of those things. In cinema, he could act as a tyrant. Which is a whole other argument about whether he would even be allowed to make these films today.

PRICKETT: Probably, as long as his abuses weren’t too sexual. Whether he or anyone would be able to make these kinds of films at this rate in this economy is the bigger question. Who would finance? Where can you get that kind of cash?

PENMAN: That’s something I think about, having been a freelance writer for so long. It would be impossible to start, today, the career I have now in a city like London or New York. I don’t know how any young person lives here without rich parents.

PRICKETT: I can’t believe I have to say this to the expert on Fassbinder—prostitution. Gary [Indiana] says the difference between Warhol and Fassbinder is that Fassbinder paid his actors. Warhol treated his stars worse than prostitutes. Some of them were prostitutes, which meant that they essentially lost money whenever they performed for him instead of for johns. Fassbinder liked for his women to look like, and sometimes play, prostitutes, but they were prostitutes that looked like stars.

PENMAN: People kept wanting to be part of Fassbinder’s films no matter how badly he behaved. And, by the way, I do think that freedom at times was collective, that he encouraged his actors and his collaborators to make their own choices. Though of course they were all also trapped, like in Chinese Roulette, trapped by the mounting approbation and prestige and cache and all that, and I think also by the fear that if they said “no” to him even once they’d never be invited again.

PRICKETT: How did you decide on the form of the book?

PENMAN: I wrote it in a kind of fever dream. It was far more work, if anything, on the montage and the putting together of the pieces. I think if I did it again the one thing I might change is taking the numbers away, to make it feel even more like a film strip. It was deliberately meant to create a kind of flicker effect rather than the standard biography. This is meant to be sort of—

PRICKETT: Refractory.

PENMAN: It’s the way I like to write, the way I would write all the time if given the choice. There is a shard-like aspect to parts of the book, where I’m sort of shattering the mirror image I’ve produced. But I wasn’t picturing a broken mirror so much as a disco ball in an abandoned disco in Berlin or something, underground, sealed off, the smell of poppers in the air, though no one’s been there for 25 years.

PRICKETT: Toward the end it gets more reflective, dreamier.

PENMAN: The last third of the book is my favorite part and it was written in this kind of fugue state, almost, more or less in the order you see in the finished book. But even that took a lot of editing, a lot of trimming. It’s the kind of thing I would have done when I was young, you know? But I think he would like it, Fassbinder. Anyway, I couldn’t do the conventional thing. It’s not that I’m too good for it, it’s that I can’t.

PRICKETT: Was cocaine very different in the ‘70s and ‘80s? The way it’s shown in the movies, like the Warhol, the Studio 54 movies, it must have been a completely different thing. Euphoric, whereas now it’s… numbing.

PENMAN: Well, there was pharmaceutical cocaine, which was prescribed by doctors to rich people for many years, and which seemed to function more like a mood enhancer than a stimulant. I think for some people, as hard as it is to believe, cocaine actually had a levelling effect.

PRICKETT: Like the cocaine Freud did.

PENMAN: Yes, and then there was street cocaine. But even street cocaine was different—I would say until the ‘80s. I mean, cocaine was associated in the punk years with Linda Ronstadt and the Eagles and all this mellow, mellow rock, what they now call “yacht rock,” and I couldn’t work it out, because how could you mellow out if you’ve taken cocaine? But I think that what happened is that by the time it was being offered to me it was something else. I’m sure it’s only gotten worse, like most things. A lot of people who think they’re doing cocaine are really doing 45% speed, 30% talcum powder, 15% cocaine, 10% god knows what. I never liked cocaine too much anyway, that thing where you end up at the end of the night twitching and jawing. And I think it’s fatal for certain kinds of art. Because, as you say, it’s numbing, it takes people’s emotions away.

PRICKETT: Every person who’s ever read their own poetry to me has been on cocaine.

PENMAN: That would be perfect for one of my little sentences [gesturing to book].

PRICKETT: Do you think of yourself as being sentimental?

PENMAN: I do, actually. It’s a bit like Fassbinder. I think sentimentality can be a good thing but it can also be used to redeem something healthy, like what I was saying earlier about men worshipping movie gangsters. They ruin the lives of everyone around them, but they cry when they think of their dead granny. So I’d be slightly uncomfortable with the word “sentimental,” because it has loads of associations for me, but yeah, there’s a part of me that I think is like that, for good or bad.