film!

Where the Filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul Goes, Few Can Follow

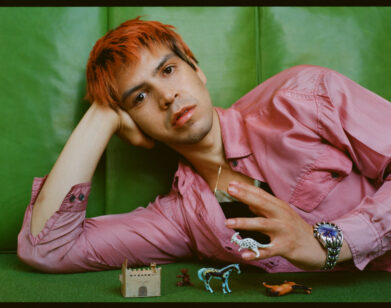

Apichatpong Weerasethakul may not be a household name in the United States, but the 51 year-old Thai filmmaker is responsible for some of the most captivating and inventive works of cinema made in the last twenty years. After building momentum with his formidable body of feature films—like the magical realist queer romance Tropical Malady (2004), and Syndromes and a Century (2006)—Weerasethakul broke through to mainstream acclaim with his fantastical, Palme D’or-winning film Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010), which became an overnight modern classic. Syndromes and a Century (2006), a vaguely autobiographical film, sparked tensions between the filmmaker and his homeland when it faced censorship from Thailand’s Cultural Surveillance Department. The director of the Department went so far as to say, “Nobody goes to see films by Apichatpong. Thai people want to see comedy. We like a laugh.” In response, Weerasethakul excised the disputed scenes from all screenings in Thailand, replacing them with a black stillness that extended, in some cases, for seven minutes.

Since then, the filmmaker has felt understandably distant from his home country. In response, he spent the past two years making Memoria, his first feature outside of Thailand, starring his longtime friend Tilda Swinton. In Memoria, Swinton’s character Jessica is troubled by a mysterious noise while in Bogotá, and attempts to articulate its shape. This aural haunting, a booming cosmic thud, was inspired by Weerasethakul’s temporary affliction with what he refers to as “exploding head syndrome.” The film has garnered immediate acclaim, both for its beauty and its unorthodox method of release—instead of premiering simultaneously in theaters worldwide, Memoria will “visit” cinemas one by one, city by city, allowing the film to exist in relative perpetuity.

I spoke with Weerasethakul over Zoom early on a Thursday morning. It was nighttime where he was, and he had just returned home from a New York press tour. A conversation with Weerasethakul unfolds much like the films he makes. The filmmaker is soft-spoken, and his thoughts, carefully considered, carry an air of mystery that is punctuated by the occasional broad smile or shy laugh. Though our conversation was quiet, Weerasethakul divulged a few personal revelations toward the end, brought on by a recent ayahuasca trip. This felt fitting, coming from an artist whose work affects others so deeply with its gentle psychedelic magic.

———

CONOR WILLIAMS: Your new film Memoria is so haunting and beautiful. It’s your first film in English, and you made it with your friend Tilda Swinton. How did that relationship begin? Where did you guys meet?

APICHATPONG WEERASETHAKUL: We tried to remember, but we can’t pinpoint it. She saw Tropical Malady in 2004, and that’s when she says she met me. We emailed back and forth and met in London, but I don’t remember what year. Later, we collaborated on a film festival in Thailand, and met here and there. We were always talking about working on a feature together. When I went to Colombia in 2017 I said, “Hey, I think I found our place.” We shot it in 2019, two years later.

WILLIAMS: Can you talk about the process of scouting locations for the film? You’ve said that you both wanted to feel lost in a way, or unfamiliar with your surroundings. What was it like coming to a place as a stranger?

WEERASETHAKUL: That’s the key, to immerse oneself. I had my own issues at that time, personal and career-wise. I was upset about the political situation in Thailand, and all the things I wanted to do but couldn’t. I just thought, “I need to start anew in Colombia.” When I started making films twenty-something years ago, I was very innocent, and I tried to operate that way again on this film. I wanted to open up my eyes and ears to everything. The stories of people. To lessen my own voice and my own problem by taking in others. It was quite therapeutic. The idea of the film came later. When I started to feel well mentally, this idea started to arise. It’s about letting oneself go. I think the film reflects that kind of being…just being.

WILLIAMS: Your film Syndromes and a Century was censored in Thailand. It seems they wanted you to cut out some of the best scenes in the film! What do you think of the American system of filmmaking?

WEERASETHAKUL: Well, I don’t really know what the American system is. When I made Uncle Boonmee, I had been yearning back to my early childhood media–the radio, royal costume dramas, films with a very slow pace and a particular kind of lighting and acting. But what drove me to Colombia was something else, beyond what happened with Syndromes and a Century. In 2015, I was doing Cemetery of Splendor in my hometown. The political situation has become more conservative, and there’s a lot of repression going on. I think it shows in the film. When I made Memoria in 2020, COVID had started, and the students rose up, because there was so much pressure, and they just needed to push back. Those huge demonstrations still echo. I think we’ve reached a turning point.

WILLIAMS: After you made Uncle Boonmee, you said you wanted to make a political film. Is this it?

WEERASETHAKUL: Maybe in the Colombian context. We premiered the film in Bogotá and people approached the film from a very political angle. A lot of them resonate with this sense of anticipation in the film, it was a reminder of twenty years ago, when it felt like anything could happen. The sound of gunfire, or a bomb. But that’s also what the film was inspired by. Moments of not knowing, waiting.

WILLIAMS: Tilda’s character is haunted by this noise, but everyone else in the film is haunted by the noise of history.

WEERASETHAKUL: Yes. And it’s a mixture of the personal and the social. When you experience some bang, some huge event in your life, you’re out of sync for a while. Out of sync with everything. I think throughout the film, she’s in that state. Being thrown off her axis and trying to get back. I think we all have moments like that, when we experience heartbreak or loss.

WILLIAMS: A lot has been said about the rollout of the film, your plan for exhibiting it. Some people find it unusual, but you’re used to showing your work in a museum context. What was your thought process?

WEERASETHAKUL: It was a secret dream of mine, but NEON actually proposed it. After Cannes, we realized the film worked best in the theatrical space, because of the collective experience and the sound system. So when we started to select festivals, I voiced my opinion that I didn’t want to go to festivals that had online screenings. For me, it’s a way to make the film reach more people. Instead of major cities, you can go to smaller places. Of course, I think a pirated version will already be out by that point. But for the people who want to see it, I want them to experience it in its intended form.

WILLIAMS: You’ve said before that you don’t mind people falling asleep in your films. Abbas Kiarostami said he likes movies that make him fall asleep in the theater. Do you get ideas for your films from dreams?

WEERASETHAKUL: Not necessarily the story, but maybe I’m inspired by the logic, or non-logic, of dreams. I’ve been keeping a dream journal.

WILLIAMS: The visual language of dreams is so related to that of cinema.

WEERASETHAKUL: It’s so closely linked—the sleep cycle is 90 minutes. That’s the length of a normal movie. And now we have VR that can make things feel closer to a dream, where we can really navigate and look around. Cinema is really evolving toward biology.

WILLIAMS: You’ve mentioned wanting to do something with VR.

WEERASETHAKUL: I’m doing one now, but I feel like we’re very early with the technology. It’s almost like we’re in the VHS stage in terms of quality— the big machine is really cumbersome.

WILLIAMS: I read a recent article that basically called you “David Lynch from Thailand.” I don’t necessarily agree, or think that a comparison like that is super relevant, but both of you give your viewers what he calls “room to dream.” Does a comparison like that bother you?

WEERASETHAKUL: Oh, not at all! You can compare me to anything! Especially David Lynch. It’s an honor. But I feel a bit hesitant because I don’t know much about his films. I don’t watch many films. I went to a party last month and I said I had never seen Twin Peaks and the lady I was talking to almost fell off her chair! She was like, “What?!” It was almost like a crime. [Laughs]

WILLIAMS: Who are some filmmakers that inspired you?

WEERASETHAKUL: Too many! Early experimental American filmmakers–Bruce Baille, Maya Deren, Andy Warhol. And of course Béla Tarr, New Taiwanese Cinema, Iranian cinema. I watched these films in Chicago in the early ’90s, and when I started to make my own movies in the 2000s, I stopped watching movies.

WILLIAMS: You’re a queer filmmaker. I would say your films are queer not just because they deal with homosexuality, but because they suggest different ways of being.

WEERASETHAKUL: To me, queer means anything can happen. It’s about openness to possibilities. I’m in debt to those experimental works. Living in Thailand, it’s quite a liberating action to make this in a cinema culture that is tightly censored and controlled.

WILLIAMS: You mentioned that the inspiration for Memoria was political, but it also came from a personal ailment of yours. Can you talk about that?

WEERASETHAKUL: A few years before I came to Colombia, I started hearing this sound, in the early morning, when I was in between being subconscious and awakening. I don’t know how to explain it. It’s not a sound, it’s something inside. Only you experience it. I think that’s one thing that inspired the film, but another thing I was the issue of, “How do I express this? How do I communicate this feeling?” In Memoria, I tried my best.

WILLIAMS: Was it born out of any kind of grief?

WEERASETHAKUL: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Do you think the film helped you resolve that?

WEERASETHAKUL: You know, I made a new family in Colombia. I tried ayahuasca, and I think that really opened my brain. Since then, I’ve been looking at how our brain works, and I feel that I no longer am confined to Thailand or this city. I’m aware of this borderless landscape. We’re swimming in the same river, and that’s beautiful, I think. It was a revelation beyond the making of Memoria.