Viggo Mortensen, Man of the World

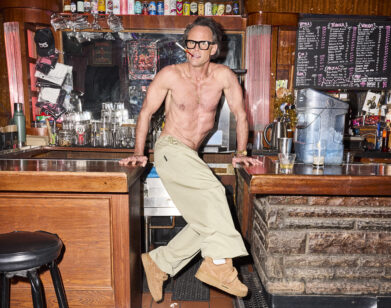

ABOVE: VIGGO MORTENSEN IN FAR FROM MEN. PHOTO COURTESY OF MICHAEL CROTTO/TRIBECA FILMS

In a small schoolhouse deep in the Atlas Mountains, a Pied-Noir named Daru teaches French history and culture to a group of local children. In his sympathies and spirit, he is Algerian: he was born and raised in the country and buried both of his parents there. But it is the 1950s, the Algerian independence movement is growing, and allegiances are allocated by ethnicity. One evening, a man delivers a prisoner to Daru. The prisoner has killed his cousin, and it is Daru’s duty as a French citizen to deliver him to his trial, and ultimately his death. Daru resists, but eventually sets off with the prisoner through the mountains to the nearest colonial town.

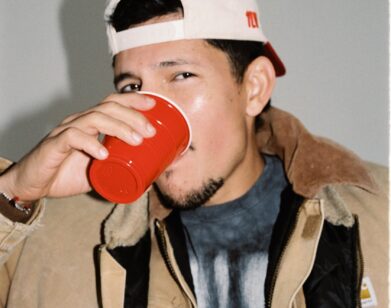

Based on a short story by Albert Camus and adapted and directed by David Oelhoffen, Far From Men (Loin des hommes) premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival last September and recently screened at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York. Viggo Mortensen, speaking solely French and Arabic, stars as Daru, with French actor Reda Kateb playing the part of the prisoner Mohamed.

Now 56, the Danish-American Mortensen made his film debut in Peter Weir’s Witness (1985), became an international star via Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings series in the early 2000s, and was nominated for the Oscar for Best Actor for 2007’s Eastern Promises. In recent years, Mortensen has stuck to small independent films: last year’s Patricia Highsmith adaptation The Two Faces of January, Cannes favorite Jauja, and David Cronenberg’s 2011 Freud/Jung drama A Dangerous Method. Joining Far From Men was, Mortensen explains, one of “the quickest decisions” he’s made in a long time.

EMMA BROWN: I know you are a fan of Camus, had you read the story Loin des hommes is based on before you signed up to do the film?

VIGGIO MORTENSEN: I think I read the story a long time ago because I remember the collection. When I read the script, it sounded similar in my head but then there are stories like that: two men that seem very different end up getting along by going through a difficult experience together—a hard journey in this case. When I took French in college I re-read The Stranger in French [and] The Plague and his play Caligula. By the time this movie came around, I had read most of his stuff, but I hadn’t read a lot of his early writing, which I ended up doing in the time before we started shooting. His chronicles, his journals, his correspondences, his journalism. His collected writings before World War II when he was still living in Algeria and he was talking about the Berber population—about the Arabs—and about a lot of the problems with racism and injustice in his native country. That I found very instructive.

BROWN: Your character in Loin des hommes will always be too French for the Algerians, and not French enough for the French. Obviously there are a lot of downsides to being a perpetual outsider, but what are the benefits?

MORTENSEN: I can identify that in some way. I was born in New York but as a baby moved to Venezuela and Argentina. I’ve also lived in Denmark, where my father’s from. I’ve traveled a lot, and having that sort of background probably increased the chance that I was going to remain curious as an adult about people who are different. Kids play together so easily with all kinds of kids; they just jump right in—they’re uninhibited in a sense. As you get older, you get stuck in your ways; just as you become stiffer physically, you also become stiffer mentally and more narrow-minded unless you make a conscious effort to keep yourself flexible. Having a mixed background and feeling a little bit like a fish out of water in most places can be a benefit. I certainly think it helps in terms of the acting, because that’s what an actor does. I look at my job as looking at the world from points of view that are different from mine—sometimes radically different from mine.

[But] people are becoming more intimately acquainted with people who are different than them—it’s not so unusual anymore. When I was 11, I moved to the United States with my two brothers and my mom. We moved to northern New York, up near the Canadian border, from Argentina, and there was nobody there that spoke Spanish, and because there was no internet at the time, not even cable TV yet, I lost the connection with my childhood friends and the culture I had been brought up with for my first decade completely. That doesn’t happen now. Now there are all kinds of people from all kinds of backgrounds who speak all kinds of languages; even in the more remote areas, you’ll find people who speak Spanish, for example. Because of the internet, satellite TV, and the digital world, you can stay in touch, you can learn about other people from a young age. It’s easier and easier to remind yourself that it’s not you against the world. It’s a point of view, too. You have all the tools to communicate better and only check in with what you already agree with. It depends how you use it, I suppose.

BROWN: Were you self-conscious about being multi-national as a child?

MORTENSEN: No, I didn’t think about it. As a kid, I don’t think you do unless someone brings it to your attention. In Argentina it was very rare because I sounded like them and acted like them. I didn’t look like most of them because I was a real toe-head. Every once in a while, someone would call me a foreigner or a Yankee, or whatever. In the United States, someone might say something, like how kids do, to point out that you’re different. That would come as a surprise to me. As you get old, you either get defensive about it or you accept it and you reach out, because you realize the world’s full of people like that.

BROWN: The ending of Loin des hommes diverges from Camus’ original short story. Do you think it’s important for it to be a bit more optimistic?

MORTENSEN: I think it’s justified completely. There are still no guarantees, we still don’t know what’s going to happen to either of them in the end, but the choice that’s made by Mohamed is earned by the story and by the things Mohamed learns on his own. It’s not like my character is teaching Mohamed anything; both characters learn about themselves by learning about the other. We had intended to shoot it both ways, and when we got to that day, we had already shot so much it seemed that that was the way it would go. Without giving it away, the way it’s handled is an organic way and not an overly sentimental way. I don’t think that’s in any way a betrayal to the story, I think that what David Oelhoffen did to expand on the story was very true to Camus. He looked at Camus’s short story and all the things I’ve read as well—the correspondence, a lot of his other writings. He added those things very carefully and he opened the story up.

BROWN: Do you think you need to like a character in order to play them?

MORTENSEN: I think it’s my job to like any character I play—to understand and appreciate a character, to look at the world as much as possible from their point of view. I don’t look at it just technically: learn the lines, figure out what gestures I want to bring and play, and that’s it. I like to learn as much as I can about the person, and see what happens.

BROWN: Has there ever been a character that’s been particularly difficult to crack into?

MORTENSEN: Not for long. I played Lucifer once, which is sort of a difficult character to research. I thought to myself, “We all have the potential to be selfish, to be cruel—at least to think evil thoughts, even if we don’t ever act out on them. Even if we don’t ever think we behave badly, we probably do more than we realize.” So I put that as a starting point, and that was a different exercise. The only thing that I always do—because I think you have to be flexible above all as an actor; different characters have different demands, actors that you work with are different in their approach, or how you get along or don’t get along with them —is once I’ve taken on a job, even just to do one scene in a movie, I ask myself, “What’s happened the moment the kid was born, until page one of the script?” To answer that simple question, I have an infinite amount of work to do. And I enjoy that part as much as I enjoy any part of making movies.

BROWN: I heard that David Oelhoffen saw a video of you speaking French, and that’s what made him approach you for the role. Is that true?

MORTENSEN: I think it was a producer that alerted him to the fact that he had seen something on YouTube where I was introducing Guy LaFleur, who is a French Canadian [ice hockey player] from the Montreal Canadiens, which is a team I’ve been a fan of since adolescence. I was invited during their centennial, which was in December of 2009, to go to Montreal and present Guy LaFleur. It was a real honor, and being that it was him and being that it was in Montreal, I thought I should do it in French. I had learned French while living across the St. Lawrence River from that part of Canada. It was pretty brief—probably about 20 or 30 seconds of video or audio of me speaking French. The director had told the producer that, in writing the script, he was imagining an actor of my type, whatever that means. The the producer got in touch with my agent and said, “Could you do a whole movie in French?” and I said, “Who knows, but I could try.”

FAR FROM MEN (TRIBECA FILMS) IS CURRENTLY SCREENING AT LAEMMLE MUSIC HALL IN LOS ANGELES AND CINEMA VILLAGE IN NEW YORK CITY, AND IS AVAILABLE VIA VOD.