Tomas Alfredson on Remaking a Classic

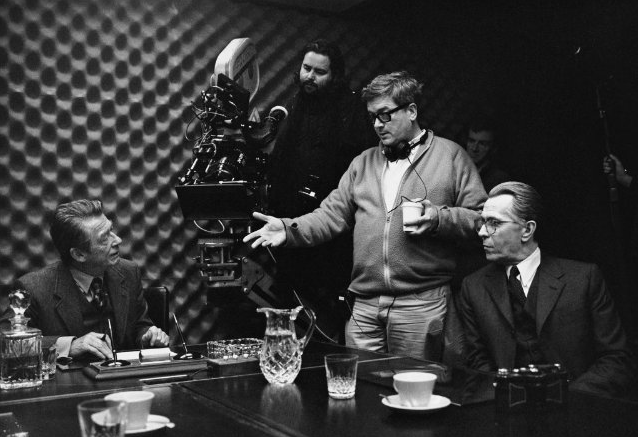

ABOVE: TOMAS ALFREDSON (SECOND FROM RIGHT) ON THE SET OF TINKER TAILOR SOLDIER SPY.

After the success of Let the Right One In, the suburban Stockholm-set, chilly child-vampire flick, the last thing people expected director Tomas Alfredson to do was make a spy movie, in English. And not just any spy movie, but the most British of spy stories, based on the famous source material by the very British John le Carré. Oh yeah, and on top of all that, it had already been made, as a groundbreaking BBC series in 1979 starring the much-loved Alec Guinness.

Let’s give it up for interesting choices and defying expectations, because Alfredson’s take on Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy is heart-pounding, hypnotic, and exceptionally crafted. Starring a well-known cast of British actors in essential supporting roles – every detail in essential in this films—the film is topped off by Gary Oldman as the main character, a British Intelligence lifer who is pushed out, later to be brought back into the fold to sniff out a mole buried deep in the unit.

Interview spoke with Alfredson about research, his meticulous planning, and how filmmaking isn’t an intellectual process.

CRAIG HUBERT: I saw the film the other night and really enjoyed it.

TOMAS ALFREDSON: Great, thank you.

HUBERT: I’m a big fan of the book as well—

ALFREDSON: No disappointments? [laughs]

HUBERT: No, no. It’s hard to go into an adaptation of a work you enjoy and not feel that it’s not going to live up to what is inside your head. But you did really interesting things with the source material.

ALFREDSON: We moved stuff around a little, yeah.

HUBERT: What was it, initially, that interested you in the book?

ALFREDSON: I think it was the tragedy of the soldiers of the Cold War, what kind of people would want to be recruited into that war. And the specifications for those soldiers were quite different from those in a hot war—what were they thinking, and what did they want from them. And the loneliness, as we see in the film, it even affects their love life; it gets into every room in your head. It’s the sacrifices these people made.

HUBERT: There is an interesting moment in the film when Smiley tells his partner he needs to “clean up,” which means he has to go home and break off his relationship with his partner.

ALFREDSON: Yeah, yeah. Right.

HUBERT: Were you a fan of John le Carré’s work before you started the project?

ALFREDSON: Yes, I was, and I clearly remembered, in the 1970s, when the TV series was aired in Sweden. I think I was a little too young to understand it, but I saw it. Later on, in my early 20s, I read the books—or at least the Karla Trilogy, and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

HUBERT: When you take on a project like this, where do you begin? What kind of research do you start with?

ALFREDSON: Well, research can be so many different things. I think a lot of filmmakers and actors refer to their research—”Oh, I did this and that, for this and that film”—and it can be so many different things. For instance, I think this film is very much about loyalty, and friendship, and betrayal. How do your eyes look when you betray your best friend? That is a topic of research, as much as research into what happened during the Cold War. Sometimes people do research on the wrong topics.

HUBERT: Do you any type of visual research, or any out-of-the-ordinary types of research?

ALFREDSON: I never look at films when I do films. I try to be an ordinary movie-goer as much as possible. I try to inspire myself—listening to music, looking at art, those types of things.

HUBERT: I’m interested in what you said about the eyes, because the whole movie is about eyes, in a way. Especially the beginning sequence outside the café, it’s composed almost completely with looks.

ALFREDSON: It’s all eyes, yeah.

HUBERT: It reminded me of a Sergio Leone Western.

ALFREDSON: That’s interesting. No one’s said that, but it’s true. It’s so much about the eyes—what the eyes do, what they see, what they hide, or conceal. And the camera is not just a camera; it’s also a couple of eyes. So we decided to try to create a sort of voyeuristic perspective on what’s happening. There might be a third person in the room constantly. A third pair of eyes.

HUBERT: That sequence, and many others in the film, are very tightly constructed. I was curious of what the post-production was like on the film, and how much time you spent, for lack of a better word, tinkering with the edit.

ALFREDSON: [laughs] Yeah, a lot. I’m an editor myself, from the beginning, so I’m very active in that process. I work with a guy named Magnus [Jonason], who is a storyboard artist—we storyboard a lot of what we did in the film. When you work with storyboards, you get into very interesting discussions of what the scene is about, and what you can do with the imagery. The Budapest sequence, in the beginning of the film, is extremely—thoroughly—boarded. It’s almost exactly as it was planned; it’s like clockwork, that scene, exactly where people are standing and looking at each other. It’s almost without any words.

HUBERT: Are you as heavily involved in the sound design as well? When you mentioned the clock, it reminded me of the sound of the clock ticking, which appears a few times in the film. You also you silence in really interesting ways.

ALFREDSON: I really like to be involved in the sound editing process. Silence is a very important actor. Silence is like a white canvas—if you draw two black dots on a white canvas, you need the white in between the dots to understand the difference between them. With sound, it works in the same way. If you surround sounds, particular sounds, with silence, you hear them in a different way. You can play around a lot with levels. Like [points down at my shoes] you could hear your shoes moving, as they are now, in a very loud way, unnaturally, and that will bring something to the scene. Some much of sound today is layers, and layers, and layers of atmosphere put together—you don’t hear those things.

HUBERT: On the surface, in terms of the content, this film appears very different from your previous film, Let the Right One In. But there are some similarities, and I was wondering if you approached them differently, given they very different source material for each.

ALFREDSON: It’s a very emotional process. You try to use as much of your brain as possible, but it’s not that intellectual. You start. You start digging, and suddenly you’ve done a lot, if your turn around as see, “Oh, I didn’t realize I’ve been digging here for two months.” It’s not that I have a birds view when I start, it’s just, “Okay, let’s start digging.” I usually say to people that ask me, during production, how about this, and how will this turn out, and can you give me answers about that scene, and how will it look. I try to say, “I don’t know, I’ve never done this film before. Let’s explore.”

TINKER TAILOR SOLDIER SPY IS OUT IN THEATERS TODAY.