NYFF

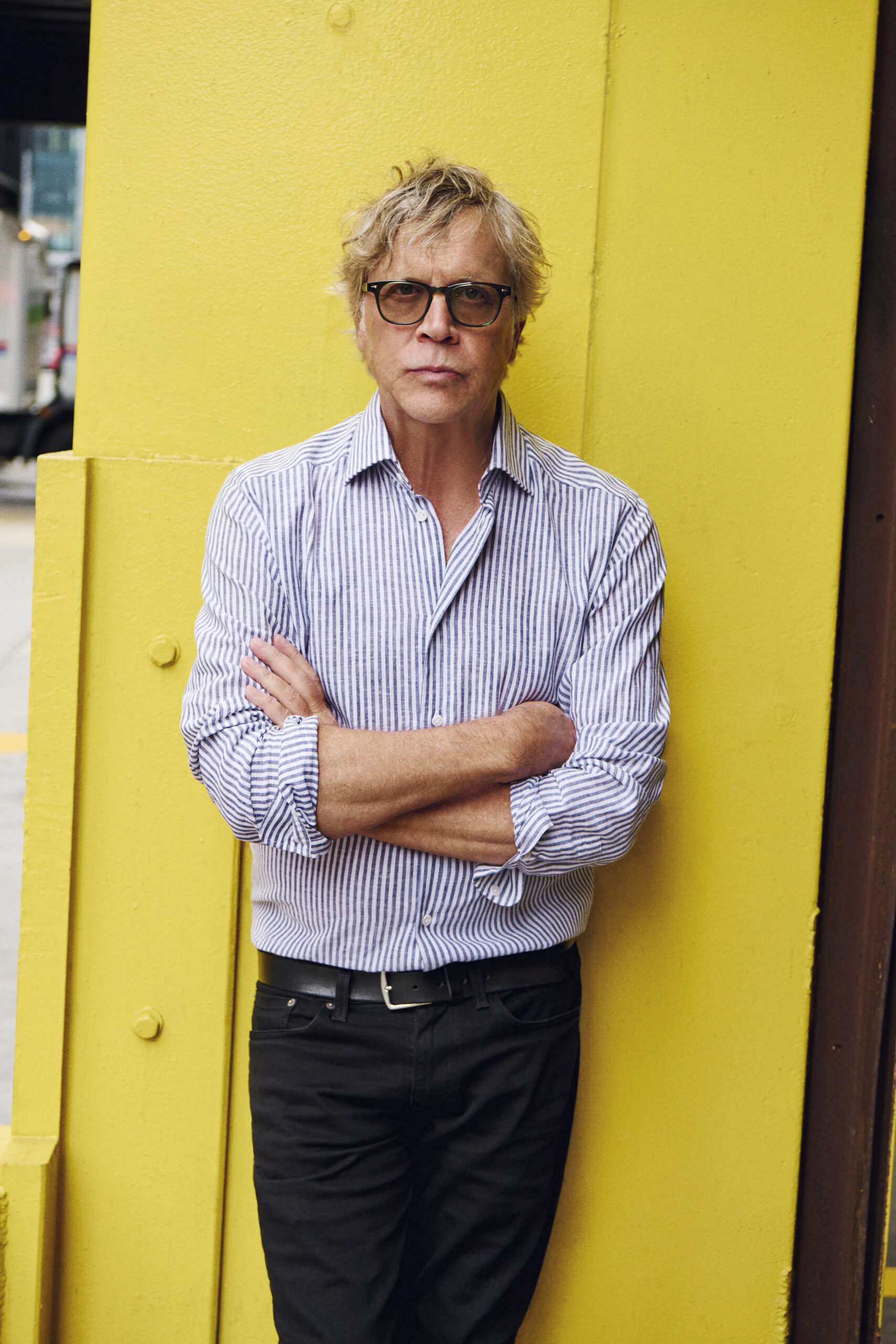

Todd Haynes on the Making and Meaning of May December

Beginning nearly 30 years ago, with Safe, the director Todd Haynes has been making what he calls “image books” for all his films, exhaustive almanacs of the visual, cinematic, and thematic references governing each project, which he distributes to the cast and crew during production. Last week, on the 35th floor of the Mandarin Oriental, he pulled the image book for his latest film, May December, from his black backpack with the ebullience of a freshman arriving on campus. “See?” he said. “I came prepared.” Inside were still photographs of the house on Tybee Island where the film was shot, its windows wet with an inauspicious fog, and images from Persona, The Graduate, and Manhattan, each of which helped Haynes develop his film’s mordant sense of humor. In an early scene, for instance, Julianne Moore’s character, Gracie, receives a box of literal shit in the mail. “This happens sometimes,” she says, before passing the excrement off to her much-younger husband Joe, played by Charles Melton, like it’s an electricity bill.

Now, why would Gracie be receiving a box of shit? Decades earlier, she was a tabloid fixture for having an affair with Joe, then a seventh-grader who worked for Gracie at the local pet store. In prison, she gave birth to his child, now a high school senior preparing to go off to college. And, as the events of May December begin, the movie star Elizabeth Berry, brought to life with a kind of menacing ambition by Natalie Portman, has touched down in Georgia to study Gracie, who she’ll be playing in an upcoming biopic. It’s a familiar device—the comely interloper coming to disrupt the small-town peace—but Haynes, as he often does, subverts expectation at every turn. Elizabeth, we discover, is not so much an audience surrogate as she is a ruthlessly extractive force, for whom the conventions of method acting (she works in service of “truth,” she tells a room of acting students) serve as an excuse to further destabilize Gracie and Joe’s lopsided partnership and rip open old wounds. On the eve of the New York Film Festival, where May December made its North American premiere, Haynes talked to me about the film’s “in-your-face” score, the recent retrospective of his work at the Pompidou in Paris, and why, unlike Portman’s character, the pursuit of truth doesn’t interest him.

———

JAKE NEVINS: Hey there, Todd.

TODD HAYNES: How are you?

NEVINS: I’m good. It’s great to meet you.

HAYNES: Nice to meet you, too. I wish we could get a better view. Is there a table with a better view somewhere?

NEVINS: Trump Tower isn’t good enough for you?

HAYNES: Is that what that is?

NEVINS: Yeah, I believe so.

HAYNES: Fuck! Not fun.

NEVINS: I know. It casts a dark shadow.

HAYNES: Did he just lose control of it because of his business?

NEVINS: Maybe? I’m sure he did. But anyway, how’s festival season treating you?

HAYNES: I’m good. We just checked and tested the print at Alice Tully Hall and it sounded great. I just came two days ago from Spain, where I was at the San Sebastian Film Festival. I’ve gone several times and it’s just such a pleasure.

NEVINS: Do you typically enjoy going from festival to festival? It seems like a lot.

HAYNES: It’s work, especially without my beloved actors and Samy [Burch], the writer, but she’ll be able to come to New York tomorrow, which is such great news. It really depends on the festival. Although we had a fantastic premiere at Cannes, so many of the people who were in the movie came on their own tickets. It’s intense, and Cannes is a formidable place to premiere one’s work. We went without a distributor. But the whole experience with this movie, from making it with everybody in Savannah, just set a tone. It’s just been a very uniquely pleasurable creative process and it’s lightened it all. So the burden of premieres and working and talking about the movie has been sort of commensurate in that way.

NEVINS: What was uniquely pleasurable about the production?

HAYNES: Every movie is different. And every movie’s hard. My films have always been experiments with, at times, an inordinate amount of ambition and trying to get a certain amount of stuff shot with limited resources and time, which was absolutely true in this case. I’ve worked with incredible creative partners throughout my career—and actors, obviously. But something about this one happened kind of quickly. My schedule changed. Openings occurred in Julianne [Moore] and Natalie [Portman’s] schedules that aligned in the fall of last year and we sort of all jumped on it. We changed the location of where the film would be set. And then some accidents happened. Ed Lachman, who has been shooting my movies since Far From Heaven in 2002, broke his femur bone and couldn’t shoot the movie. So I had to get a new DP like, two weeks before pre-production. I’d never worked with Sam Lisenco, the production designer, before, but we had been planning a movie prior to this that didn’t happen. It was a lot of new relationships and somehow that contributed to this fresh energy. I made the decision at a certain point to just be open about all my ideas and bring everybody into the process. We shot it in 23 days. I mean, the thing was just nuts. So we had to have a plan that worked aesthetically and conceptually with the script. I wasn’t pulling my hair out and freaking out the way everyone does in movies at some point.

NEVINS: It sounds like there was still a real spark to it, despite the forced economy of the production.

HAYNES: It took a plan and the plan, as you see in the finished film, had very much to do with a very restrained camera and a lot of single-shot scenes, and a lot of scenes using the mirror as a motif. The kind of mood I wanted to create and the kind of tonal elements I wanted to play with, it all made sense to me conceptually. The music was an early accompaniment to this whole experiment and this sort of visual style I stumbled on. I saw The Go-Between, [directed by] Joseph Losey in ’71. It’s a movie that had sort of fallen out of distribution or visibility for decades. I think I saw it when I was a kid and hadn’t seen it since. And I heard that Michel Legrand score and I was just like, “What the fuck?” It opens up your eyes, it pricks up your ears. You’re watching the frame with this acute attention to what this ominous, hardcore, in-your-face score is portending. And I thought, “That’s what this movie needs.” It needs that excitement. So we literally performed to it. We played that music during the shoot, in every single scene where there wasn’t dialogue, where I had a music cue placed. It was thrilling.

NEVINS: I’m glad you mentioned the score. Because, as a long-time admirer of your work, it struck me as a more willful use of music than I’d seen in your other films.

HAYNES: Oh, absolutely. Because I borrowed it from this other film.

NEVINS: I also wanted to ask you about using Natalie as the framing device.

HAYNES: [Laughs] I thought you said “flaming” device.

NEVINS: Well, that too.

HAYNES: Right.

NEVINS: So the film trades on this familiar trope, where the “visitor,” per se, functions as a sort of audience stand-in. Oftentimes the visitor is a journalist profiling someone famous, like in Jackie or Frost/Nixon or even Almost Famous. But here, the visitor is a famous actor. And she reveals herself to be rather unreliable and, in many ways, just as craven as Julianne’s character. So she almost has a sort of distancing effect.

HAYNES: Well, in both Natalie and Julianne, I’m working with actors of such incredible intellect and complexity and an interest in disturbing expectations, or challenging them. I was in the company of people who all knew what we dug about this. So we came with the tools, I think, to help find a visual, cinematic way of expressing that. I would’ve been completely satisfied if audiences just were like, “Wow, I was really interested in all the distances and the long takes and the self-conscious looks to the camera lens.” Or, “I thought of Bergman or Godard,” because those are the sources I was looking to. But somehow, with the humor that’s inherent in the style and the performances and the music, all the tonal things we were describing, no one even seems to notice. They are completely engaged, and yet they’re feeling all of that discomfort. But they’re not thinking of it as a distancing experiment. The film is very pleasurable, as it turns out. And you never know exactly what the experience will be like.

NEVINS: I’m glad you mentioned those influences, because I know you make pretty comprehensive “image books” for all your films.

HAYNES: Yes.

NEVINS: What was in the one for May December?

HAYNES: [Pulls out “Image Book”].

NEVINS: Oh my goodness.

HAYNES: See? I came prepared. It also inspired a companion piece, because I knew I was having a retrospective at the Pompidou in May before we ever knew we would be in competition at Cannes. And they ask for an original short film from the directors who are getting a retrospective. So there were things we shot in addition to the film that were for a short film called Image Book, which is dedicated to Godard, who died when we were in pre-production.

NEVINS: Did everyone get a copy of this?

HAYNES: Oh, yeah. But they didn’t get a bound copy.

NEVINS: There’s no budget for that.

HAYNES: No budget for that. That’s out of my own pocket. But I would send everyone this image book and I would say, “Play the music from The Go-Between as you turn the pages.” So it was just another example of how we were all drawing from the same references. As you can see, this book includes references from Persona and examples of direct address and also tries, as most of my image books do, to put it into a linear format. So it starts from the beginning of the story and includes shots of the location of the house, which Sam and I found literally following our noses in Tybee Island. I literally put a note on the guy’s door. And then the next day, while we were still in Savannah, he said, “Okay, you can come look at the house.” So we took all these pictures and it would have the precipitation lodged within the sliding glass doors in the marshy, super hot August heat. So this inspired [cinematographer] Christopher Blauvelt in appeasing my way of filtering the lenses and creating a sort of set light through the look of the film. So we have images from Savannah interwoven with other references to films that inspired the style, like The Graduate, which touches on both the theme of the older woman and younger man relationship. But also its formal minimalism, which I just find so inseparable from its humor and originality. And also the film Manhattan and its formal visual restraint. They’re both comedies, but they’re done with sustained long shots. If you could imagine The Graduate in conventional coverage, with a shot over a shot and millions of cuts, the humor of that film would be completely different, as it would be for Manhattan, without Gordon Willis’s long, beautiful wide frame and black and white cinematography.

NEVINS: Well, May December is quite funny. At a few different points, Natalie’s character is talking about her mission as an actress and she says she’s interested in “truth,” but it comes off kind of hackneyed and trite, as if it’s some boilerplate response. Is the pursuit of truth at all interesting to you?

HAYNES: No.

NEVINS: I thought you might say that.

HAYNES: Of course. And you can’t not be amused when the actor says, “I really want you to feel seen and known.” But we’re all captive to ideas about truth, authenticity, reality, particularly in the world of film and representation and storytelling. There’s a preciousness about it, and there’s an all-too-facile way of presuming that we’re all talking about the same thing and we all come from the same place, but it’s woven into all of our lives and all of our senses of how we look at the world. But yes, notions of representing reality on film have never been my driving force. And I think something really powerfully real happens to a viewer, but it’s not because what’s delivered to them is reality. Something happens between how we interpret, how we ingest, how we consume images and play them against our lives and what we know about the language of movies that is intensely powerful and real. It’s like a dream. It’s not the latent meaning where the truth lies.

NEVINS: Before our time is up, I want to ask about the retrospective at the Pompidou. Did anything interesting occur to you, seeing your body of work in its entirety?

HAYNES: The whole experience was extremely moving and extraordinary, partly because of the people who run the film department at Pompidou and how close I became with them. We had to create a catalog for the film that used hundreds of images, mostly my paintings and drawings and sketches and notes. That book will be translated into English at the Museum of the Moving Image for a retrospective that opens here at the beginning of December here. It’s like you’re dying while you’re still alive. But that’s okay. I was like, “I just want to be as present for my death as possible.” And I thought the French would sort of dig that. I had my producers there. I had Affonso Gonçalves, my editor, there, and Laura Rosenthal, my casting director. Ed Lachman was there every single night. Cate Blanchett came. Natalie Portman came twice. Cate Blanchett was there for Carol and I’m Not There. I thought Kate Winslet would just be there for a Zoom call, but she walked right into the room. Charlotte Gainsbourg was there. So yeah, I was having an elevated recognition of my life and work that I could enjoy. I felt so honored and really loved by my partners.

NEVINS: You mention all the wonderful actresses you’ve worked with, many of whom I came to love through your early work. I know you had some idols yourself as a kid, like Diana Ross, Lucille Ball, Joni Mitchell.

HAYNES: Yes, absolutely.

NEVINS: It made me wonder if, in your films, you recognize the seeds of your own boyhood fixation with women entertainers, glamor, show business, all the things that typically hold a young gay boy’s attention.

HAYNES: Absolutely. I would say yes, with the exception of it necessarily being manifest in the world of glamor and showbiz as much as just the power and complexity of female subjects that affected me from the youngest age, and was mirrored by incredibly strong and influential women in my life, from my mom to my grandmother to my sister to my art teacher. And then finding Christine [Vachon], who’s produced every single film I’ve made. We are creative partners and we are best friends. So the role that women have played outside and then within the frames of my films is multifaceted. I just had dinner with Julianne last night. It’s so hard to be doing this kind of thing without her, but yes, it’s quite evident where it all comes from.

NEVINS: Well, it appears they’re cutting us off. I could do this all day. But I appreciate you taking the time.

HAYNES: Thank you so much. It was so nice.