Skål!

Thomas Vinterberg and Mads Mikkelsen on Why Another Round Is An “Untameable Beast”

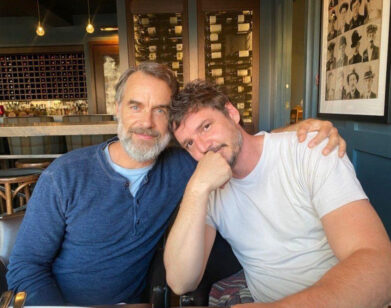

Thomas Vinterberg and Mads Mikkelsen on the set of Another Round.

A couple of years ago, in a living room in Denmark, the director Thomas Vinterberg invited his friend and collaborator, Mads Mikkelsen, to watch a YouTube video called “Two Men and a Lock.” The video, in which two men drunkenly try to put a lock on a bicycle, turned out to be Vinterberg’s pitch for his next film, about a group of middle-aged men who experiment with chronic drinking. Mads was sold. The video was the perfect encapsulation of the human condition, both dogged in its determination and tragic in its fallibility. That germ of an idea eventually became Another Round (Druk in Danish), in which a group of jaded high school teachers discover the work of Norwegian psychiatrist Finn Skårderud, who theorized that humans are born with a blood alcohol content that’s 0.05 percent too low. Naturally, they put it to the test, hiding flasks in janitors’ closets and taking swigs of Smirnoff with their morning coffee. While provocative in concept, the film delves deeper than its comic hijinks, becoming an existential meditation on middle-aged discontent. It’s been met with acclaim both in and outside its home country, and is almost a sure contender for the 2021 Oscars. Another Round marks the second time Mikkelsen and Vinterberg have joined forces; in 2012, the actor starred in The Hunt, playing a kindergarten teacher wrongfully accused of sexually abusing a child in his class—one among a bold, robust filmography that includes Dear Wendy (2005), written by Lars von Trier, and Far From the Madding Crowd (2015), the adaptation of the 1874 novel starring Carey Mulligan.

For Vinterberg, however, Another Round is his most personal work to date. In 2019, he lost his daughter in a car accident, while traveling home from Belgium with her mother. Much of the film was made in the shadow of that grief, with Vinterberg shooting largely at her school with her classmates. But in that grief, he found something like catharsis. It’s a film about “the joy of letting go of control,” as he discusses with Mikkelsen on a Zoom call during a dark Danish winter. “But also, I experienced the ultimate loss of control by losing the life of my daughter. It was like a current that we both floated with. I’ll never forget that.” —SARAH NECHAMKIN

———

MADS MIKKELSEN: [Speaking Danish] Oh, somebody else is on the line. Good. Hi there.

THOMAS VINTERBERG: Sorry for speaking our gibberish.

MIKKELSEN: We’re ready.

VINTERBERG: Let’s start with our friendship, and our working partnership. Well, I don’t know where the line between our partnership and our friendship is at the moment, as you live right next door, and our wives are hanging out, and we’re in the gym together. We occasionally talk about work as well. Don’t we?

MIKKELSEN: Yeah, it’s become a blurry line, but it’s an interesting thing. It’s a late-blooming, working relationship and friendship. I mean, we knew of each other from the get-go, back in the middle of the ’90s, and there was no way we wanted to work with each other, at that point, for a lot of reasons. We were competitors. And it was an interesting period, right? Because at that time, we were defining ourselves from what we were not. We were not like the other ones, so that’s one way of defining yourself, I guess. But a lot of small groups did that.

VINTERBERG: That was a young way of seeing things. But also, there had to be the right part. I felt I always admired you, maybe secretly, but I did admire you. And I always thought, if I should offer you something or invite you to do something, it would have to be the proper thing. And I felt with The Hunt, it was the right thing to do.

MIKKELSEN: I mean, better late than never. Maybe it was the right time. Maybe we were ready for that kind of work together. We were busy doing a lot of other things, and maybe it was the right time. We will never know. Now we’re working. This is the important part.

VINTERBERG: Right.

MIKKELSEN: But tell me, you keep saying that the story came to you, like, eight years ago. What was the original reason for that?

VINTERBERG: I felt that there had been so many moralistic tales about alcohol, and I felt a great growing sense of chastity of our country. Some people call it political correctness, but I would call it chastity and fearfulness and an over-reasonable behavior. And I wanted to point at the fact that here’s a country of people pretending to be reasonable but drinking like madmen at the same time. And I wanted to look into that. And I also very quickly realized why people are drinking and how people can elevate from drinking. Normally, an idea is something more specific than it was in this case. This was just thoughts about alcohol, really, and probably a reaction against mediocrity and boredom of this country.

MIKKELSEN: The film is traveling at this point for a lot of reasons. And one of the reasons is that it’s not only about alcohol. Alcohol, in many ways, is the kick-starter of a film about life—embracing life and celebrating life. But were you ever hesitant, in the sense that you thought it was too Danish a subject? I mean, obviously we could compare to the Finns maybe, and sometimes to the Russians. But now that you know that people have reacted to the drinking quality of the characters all around the world, and they recognize themselves in that even though we don’t have the same drinking culture, did that surprise you?

VINTERBERG: It did surprise me, but I also did learn a lesson that I think we’ve learned a couple of times before, that if things become general, people are not interested. But when things become very, very specific, and in this case, very Danish, and very, very us, then people become curious. Then it’s brought to life. I think there’s two things that are super important in what we do. One thing is that it becomes very specific and real. And another thing is that we forget about ourselves, and that we don’t have agendas. We don’t have things we want to tell. We turn the eye that way, away from us, and explore. Then people become interested.

MIKKELSEN: I think you’re right, that the more you can tell a true story from your true point of view, the more people can mirror themselves in it. As opposed to just, as you say, telling a general story. Like I’ve said a few times, this is the most Italian film you’ve made as well.

VINTERBERG: Yeah. And I’m proud of it, because I did watch a lot of those older Italian movies at film school. And they have this sort of wild, untamed, celebratory tone to it, in many cases, without the stringent narrative that we’re used to. And there’s something Central European in the way that you guys are celebrating life in the streets, which is very un-Scandinavian, to some extent.

MIKKELSEN: I agree. I think it’s also the poetry. There’s somehow a poetic note throughout the film. It doesn’t matter how dark it gets. You always have it, but I think you have it even moreso in this film.

VINTERBERG: This film is probably the most honest film I’ve done, maybe since film school. It’s so un-calculated, and it’s such a mix of genres and emotions and private strategy and joyfulness of us working together, that it was somehow beyond our control. And we were disarmed when we did it, completely disarmed because of the death of my daughter, and the whole situation this film was made under. We didn’t have our guards up, and we just did it. We just looked outwards. And there’s an element of honesty in that, which is something I’m super proud of. That’s what I’m always trying to aim for.

MIKKELSEN: I think you’re right. For that reason specifically, it felt as if people took down that defense in a way that that was uncharacteristic for a lot of us. Not that we didn’t have questions and we didn’t have things we have to figure out and struggle with, but there was a sense of daring, much more than I’ve tried before. Every time we were uncertain whether this was right or not, we just said, “You know what? Let’s give it a shot.” And that’s a rarity, I think.

VINTERBERG: When you make a movie, you always say, “I’ve never done a movie like this before.” But in this case, it was really true. I’ve never done a movie like this before. Already from writing this script, this was an untameable beast that wanted to go in all sorts of different directions. It wanted one scene with you, where you so tender and crying. And then it wanted another scene with you and your friends, making slapstick comedy, buying codfish in a store. And it insisted on having those two scenes in the same movie, which normally would have been curated and equalized and tamed. And so, the only way to work with this film was to let it be beyond our control somehow. Of course, there was a script, and there was an editing process—it was not complete anarchy, but there was something. There was a soul in the narrative in this movie that was so complicated to control.

MIKKELSEN: I agree. I remember that it was very stringent, in the sense that you have the arcs of the character, the characters were there, and there was a logic to the characters. But in some places, the logic kind of disappeared, because it was an uncontrollable film. It felt like an uncontrollable beast we were working on, and that was kind of new to me.

VINTERBERG: It’s interesting, because you’re talking about the uncontrollable, which is a word that I love these days. And uncontrollable showed itself in many ways. The film is about that. It’s about the joy of letting go of control, but also, I experienced the ultimate loss of control by losing the life of my daughter. So we were just there, in some turmoil of emotion. We’re professional enough to pull off making a movie, but it was like a current that we both floated with. It was amazing. I’ll never forget that. Mads, people are very interested in this, how to play drunk. You’re so great, so you just pulled it off.

MIKKELSEN: I think a lot of actors find it easy to do the slight drunk version, because we all know what the trick is there. We know that when you’re slightly drunk, you want to hide it. And that’s the entire goal of your character at that point, hiding that you’ve been drinking a little. And your moves become a little different, and your speech become a little more precise, and that gives you away to a degree, but you can’t get away with hiding it. So that is the approach. But once you turn up the volume, this is where we get in trouble. This is where it can become a little too much on the surface. And that was tricky. But I think that we were in good hands, knowing each other that well. So instead of being ashamed when we didn’t nail it, we would laugh with each other, because we knew exactly why it went wrong. We’ve all been there. We could nail it. What also came in handy were the Russian videos, watching all the Russian people drunk for real. That is just insanely inspiring. I mean, at least it told us that nothing was too much. There’s absolutely nothing that’s too much, because it is insane how drunk people can be.

A still from Another Round.

VINTERBERG: I don’t know if you remember, but when I tried to sell you this idea, back in my living room, 185 years ago, I think what hooked you was this video called “Two Men and a Lock.”

MIKKELSEN: Oh, it’s fantastic. But the beauty of the thing is that when you’re that drunk, obviously you don’t care what people think around you. But also, it seems as if you always have a mission. For some reason, you’re not just sitting down in a chair being drunk. No, no, no. These guys are insisting on putting this lock on a bicycle and everything that can go wrong goes wrong. And it’s just insane to watch how focused they are on this mission.

VINTERBERG: For 15 minutes. And they move about two or three meters, with this lock. It was amazing. But were you ever nervous? Were you ever nervous about the fact that you guys had to play drunk?

MIKKELSEN: No, I wasn’t nervous the day before, but I was always nervous that we didn’t nail it. Not the little tipsy things. Those, we had a good hand on. We could dial up and down. But some of the more extreme drunken things, it was difficult to find a balance, but it was inspiring to just watch around and see your friends struggling with the same thing.

VINTERBERG: I got nervous at times.

MIKKELSEN: There’s a lot that’s not in there.

VINTERBERG: Mads, people want to talk about the dance.

MIKKELSEN: Yes, of course, they do. They can talk about it.

VINTERBERG: Right. Let them talk.

MIKKELSEN: The dance is your thing, Thomas. Thomas, you wanted to see me dance. You always felt I was just unreasonably stupid, that I didn’t put that on the screen. And this film gave you an excuse. And that’s how I felt a little in the beginning. This was an excuse to see me dance. But luckily the excuse became bigger and bigger. And eventually, it was unavoidable that it had to be a dance. That was the only solution for that scene.

VINTERBERG: Sometimes in my career, I’ve realized, that the ideas behave like this: you pitch it, and you go, “Shit. You can never do that. That’s too much.” And then you do it. Those are the ones that really conquer the world. Mads, watching you that day, dancing, was a one-to-one experience of how the film is. It was our beautiful catastrophe in private life. Ida was dead, and you were dancing, and everything made sense. Everyone was so great in that moment. And you, of course, in particular, were absolutely outstanding, with your dance. And yet still behind us, there was this shadow, this deep tragedy. And I think it’s the same feeling people get at the end of this movie. Your good friend died. It’s the same feeling Martin has at the end of this movie. Your friend passed away. And yet, still, you’re weightless, and everything is possible. And that sensation is overwhelming. I remember one of my director friends, having seen the movie, he was shocked by this ending. He was crying and stuff, but he couldn’t really define what it was. He felt he was run over by a train. And that’s the first time I realized, “Okay, we might’ve done a great scene here.” Because he didn’t know what to say.

MIKKELSEN: We shot it in two days. I only remember very pure faces, almost naked human beings, standing there. And then you had the most beautiful ship in Denmark passing by in frame.

VINTERBERG: Accidentally. People who don’t know Denmark should know that this movie is a love declarant to our country. And suddenly by accident, the only ship in Denmark, which is called Denmark, passes by, in its beauty and its pride. And we just started filming, with everyone running into the frame, as the ship passed by. Yet another divine moment of shooting this.

MIKKELSEN: I believe we had a lunch break there, when you just came screaming, “Come on. Let’s shoot that scene.”

VINTERBERG: Yeah. And then you started talking about the inner emotions of the character. I was like, “I don’t give a shit.”

MIKKELSEN: Sorry about that.

VINTERBERG: That was fun.

MIKKELSEN: There is an innocence in the entire scene, when you look at all the faces. They’re all in a certain zone that has nothing to do with alcohol.

VINTERBERG: That’s right. Nobody was drunk, and everyone was pure. And everyone was in an element of ecstasy. It was cathartic. We should probably be asking ourselves, why has this film been such a success as it is right now? Why are people flocking to the cinema in Denmark, or actually, everywhere that film goes? Probably, in this world that we live in now, which is very confined, very restrained, very dark, there’s a desire and a relief in watching something that is beyond control and that has the warmth and celebration that you guys bring to it.

MIKKELSEN: I remember the first time we saw it with a crowd. No, not even with a crowd. I think it was just me and my wife in the middle of the shutdown. It was almost as if I was watching something that was illegal. There were young people celebrating, drinking from the same bottle. Some of them were kissing. And it was only half a year ago that we had that life, but it seemed as if it was decades ago. Right?

VINTERBERG: I was nervous about that.

MIKKELSEN: It was so refreshing to watch it. But at the same time, we were a little afraid there would be a backlash because of that. But it turned out that people were not ready to watch a film about the COVID shutdown yet. They wanted to see a film about life.