ANNIVERSARY

“Everyone in Hollywood Passed on This”: The Cast of the Cult Classic Jawbreaker, Reunited

It’s been on the moodboard for 25 years since its release—homaged in everything from Mean Girls to Kacey Musgraves’s “simple times” music video. It’s a scene that takes place at the top of Darren Stein’s Jawbreaker. Imperial Teen’s “Yoo Hoo” plays as the Flawless Four—Courtney Shayne (Rose McGowan), Julie “Jules” Freeman (Rebecca Gayheart), Marcie “Foxy” Fox (Julie Benz) and Elizabeth “Liz” Purr (Charlotte Ayanna)—strut in slow motion down the halls of Reagan High School. If they gave out Academy Awards for strutting, these four would be rewarded with a well-earned statuette.

It’s a textbook example of the rare jewel of the film world: the cult classic. “A cult movie is something that people discover over time and make as their own,” Darren Stein, the film’s director, has said. “It has a certain darkness, a certain subversiveness to it; something about it feels not right. And so a cult gathers around it to share in that subversive draw they feel.” To put it differently, they gather as a means to protect it with adoration.

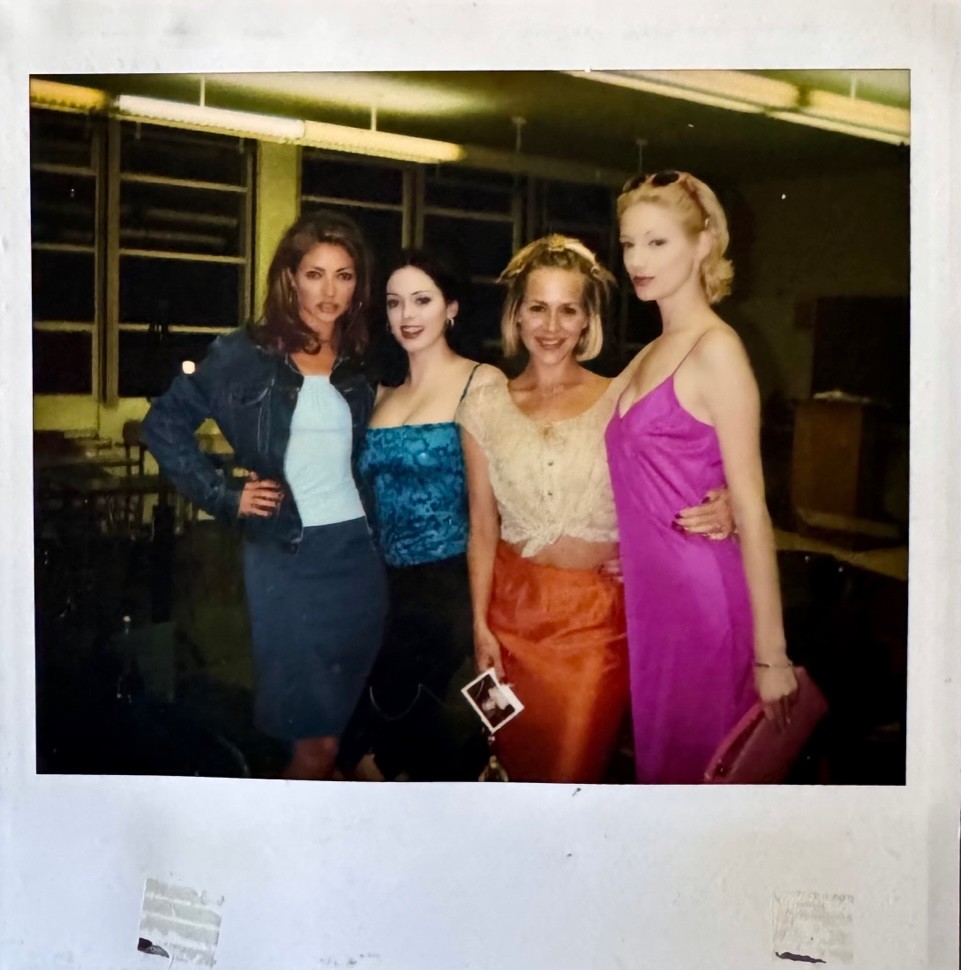

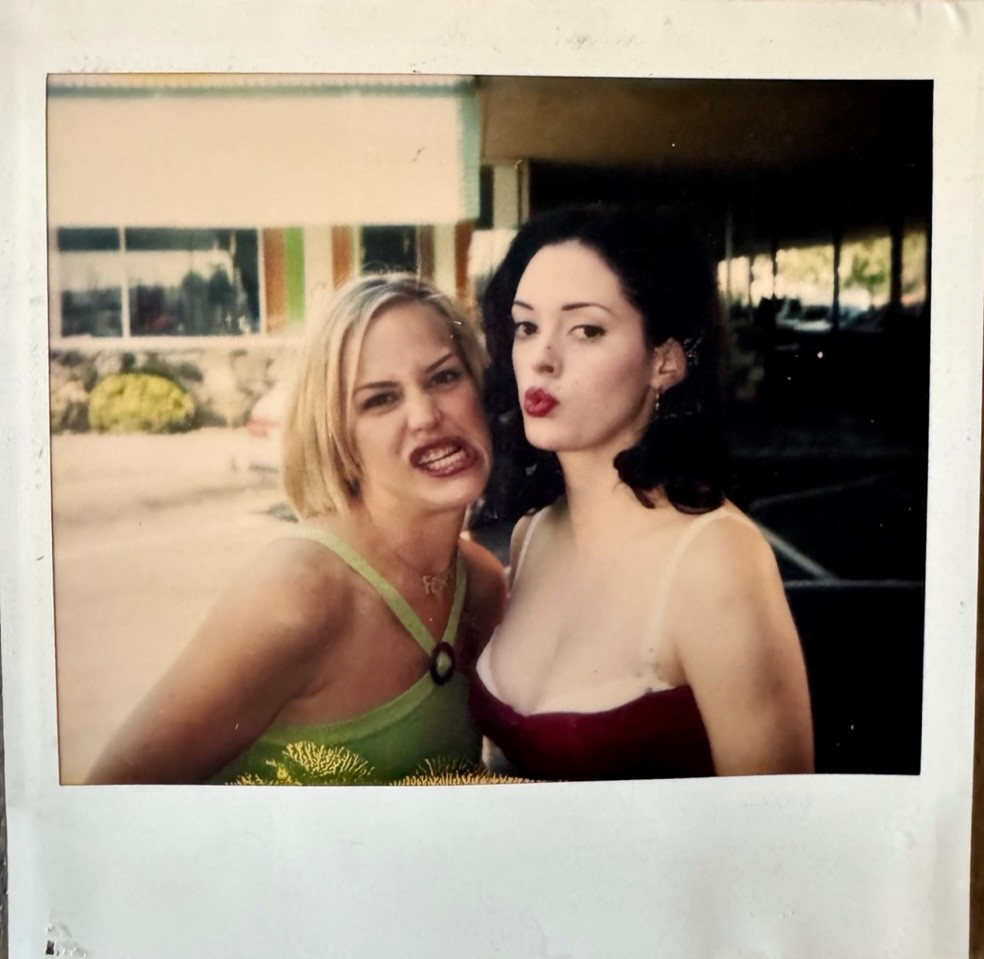

On the occasion of Jawbreaker’s 25th anniversary, Stein, Gayheart, Benz and Greer gathered at the Academy Museum last weekend for a screening in 35mm on one of the 10 remaining prints from the film’s original release. Just before their reunion, they joined me in a Zoom chat (looking like they’d collectively been passed the The Potion from Death Becomes Her) to discuss the film’s enduring legacy, unpack its distinctively campy spirit, and share never-before-heard stories about how the sauce got made.

———

EVAN ROSS KATZ: I’m going to start with a question that I’m sure you’ve answered many times in the past 25 years. Which is, why are we doing this? Why are we here today, talking about a film that was made 25 years ago, and one that is so beloved?

REBECCA GAYHEART: I can start. I have teenage daughters. It’s still resonating with audiences of that age. Kids still really want to watch Jawbreaker. I have teenage daughters, their friends, they watch it, they love it. It resonates with audiences still.

JULIE BENZ: I think that Darren did such a great job of creating a heightened version of high school life that everyone can relate to. The fashion, the music, all the elements are just classic and timeless. It withstands the test of time, really.

JUDY GREER: We were shooting and Darren said, “I’m going to make a cult classic.” And so, that’s also what we’re doing. We did it. Congratulations.

DARREN STEIN: I did not think so. I mean, saying it and having it happen are two different things. You can’t set out to make one. It has to sort of unfold that way, over the decades. Also, the story is so mythic. It’s sort of a Faustian tale about a girl who sells her soul to the devil to be popular, to belong. I think that transcends any era, because everybody wants to belong when they’re an adolescent. It’s sort of evergreen in that way.

GAYHEART: The cruel politics of high school still exists, guys.

KATZ: Absolutely. I was talking to a friend recently about films like Jawbreaker and the fact that they aren’t really made anymore. I’m also talking about Dazed and Confused, Clueless, Cruel Intentions, and we could prognosticate on why that is. But I’m wondering what you all think it was about this moment in time that allowed for so many of these films to be greenlit. And when I say these films, I think what I’m trying to get at is films that dignify the teenage experience.

GREER: Well, what movies are being made now? Because it does feel like when I auditioned for Jawbreaker, I was auditioning for just an endless amount of high school movies. Didn’t you guys go in for all that stuff? Like Cruel Intentions–

GAYHEART: Yeah.

GREER: … and 10 Things I Hate About You. And She’s All That.

GAYHEART: We all screen-tested for all those movies.

GREER: Yeah. That was just a time when it was all those high school movies…

GAYHEART: I think that generation, we weren’t parented in such a helicopter-y way, and so people heard us and saw us in a different way than teenagers are seen today. I think. We had some self-agency, and we had great ideas–

GREER: More independence.

GAYHEART: Our experiences were meaningful. And in some ways they weren’t too meaningful. Do you know what I mean? They were funny and crazy and outrageous and dangerous, and all that’s entertaining. It was just a different time. It really is hard to articulate what exactly it was, but there were definitely just tons of those movies being made. And you’re right, Judy, there’s not any right now.

GREER: But you can’t make a high school movie now without making it all about social media. It’s like, “Well, we didn’t even know what that was.” I mean, honestly, Rebecca, the first time I ever saw anyone have a phone that wasn’t plugged into the wall of their house was in your Toyota 4Runner that you drove me somewhere in once. And it plugged into your car.

GAYHEART: I don’t remember that, Judy.

GREER: Am I right about your car?

GAYHEART: Yes, you are. You have the memory of an elephant. You remember the craziest details of things.

GREER: The phone in your 4Runner. Anyway, I don’t know that you can make a high school movie now without that. I think that that is tricky water to swim in right now, with what social media has done to that generation, is doing to that generation. But it was, just to sound like a full boomer, a more innocent time. You could say goodnight to your parents and go to a house party until zero dark 30.

GAYHEART: Absolutely.

GREER: You know what I mean? That was just the way it was.

GAYHEART: And no one was taking pictures the whole time. I know kids now who don’t want to go hang out at their friend’s house, or they don’t want to go to a party, because they don’t like the way they look. And they know they’re going to be posted on a million people’s Instagrams and TikToks and Snapchats, so they’d rather stay home. They can’t just live. They have to look good to live.

BENZ: I watched that movie Brats last night.

GREER: Oh, I want to see that so bad.

BENZ: It was interesting because there were all these John Hughes teen movies in the ’80s, and we were kind of that for the ’90s. Obviously we aged out of being able to audition for teen movies, but I think that we were kind of a product. We were coming after the Brat Pack and all those ’80s films. That was what was going on in Hollywood then.

STEIN: And it was a more nihilistic time. It was Generation X, Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love, the Seattle grunge scene. I wrote Jawbreaker to see the teen film I wanted to see. I loved Heathers. Of course, I love John Hughes. Clueless, even. But Jawbreaker was my vision of high school, because I went to an all-boys school. So that was, “Oh, this is going to be the co-ed version of what I could have lived.” Also, for me, it was the velvet rage of being queer and not getting to be myself in high school, not being able to date, not being able to grow up. And so, in the script, I’m all the characters. I’m a little Fern. I’m a little bit Courtney. Courtney is my rage, Fern is my spirit animal, as far as probably the closest to how I felt. Marcie is like a dream I wanted to chase. And Julie is the happy medium of what happens when you embrace the good side of things.

GREER: When you’re a good person.

KATZ: And yet, Jawbreaker also feels like an outlier within this subgenre. And there’s a quote that Rose actually gave, in the Vice oral history, that I think sort of summarizes what we’re talking about. She said, “Darren really brought it. He had a really punk spirit. We all did. That was really essential to that production.” I’m wondering if you all could describe the ways in which this film felt distinctly punk, because I think “punk” really is that word that stood out to me in all of the reading I did about this film. That was the thing that made the bell ding.

STEIN: Well, that’s my aesthetic. I have “Sid and Nancy” tattooed on my inner wrists. I had dogs named after Sid and Nancy. But you know, I love punk music. I love the idea of nihilism, anarchy, horror, bondage, Vivienne Westwood, all those things. Sid and Nancy was a film that captured my imagination when I was 14. I think it has a lawlessness and an aesthetic and an edge that other films don’t quite have from that time. It comes from a place of otherness, and not being part of the norm, which is what punk is. It’s a rebellion against everything that’s societally approved. What do you guys think?

GAYHEART: Our attitude was punk. It trickled down into the set, the trailers, into the video village, our scenes, and our relationships. It was a vibe we all had.

STEIN: We were all so young, so it was easy to embrace that. Also, I wanted the movie to look unlike anything else I had seen, so I collaborated with this costume designer, Vikki Barrett, who loves punk. And so the references are everything from fetish, the punk scene, bondage, film noir movies, to Grease in the ’50s, and slashers from the ’80s, ’70s. Anything retro. A lot of what punk is, is a repurposing of older things in a new way. She bought everything in vintage stores, much like a punk rocker would buy the clothes they wear. That’s part of the whole general aesthetic of the film.

GREER: I mean I hadn’t really worked much before I did Jawbreaker, so I didn’t have much to compare the set to at the time. But I think in addition to the aesthetic, it was a frame of mind. And it felt like we were doing something different, because we didn’t have a big budget. It was a low budget movie, and we were fucking scrappy, man.

GAYHEART: That’s right.

GREER: Like, we had to be scrappy, and I didn’t even know at the time. I was like, “Oh my God, they’re feeding us food.” And now looking back, I’m like, “Oh, we were basically shitting in a ditch all the time.” I was like, I just thought that’s how movies were made. But no, we had to make it work. And that mentality of, “Fuck off, we’re doing this however we want to do it,” was really punk rock.

GAYHEART: I have to agree with that.

BENZ: I mean, I do think, out of the cast, I probably had the most normal high school experience that resembled the cliques within Jawbreaker. And that’s really what I related to, because I grew up in that. In high school, it was very important to be popular. I kept a clothes journal, because I wanted to get the senior superlative “Best Dressed.” I never wore the same outfit twice, in four years of high school. So I don’t really have an answer for this question.

KATZ: Rebecca and Judy, both of your jaws are dropped right now. I knew this about Julie, having read the oral history before. Are you learning this information for the first time?

GAYHEART: Yeah, I didn’t know that.

BENZ: Rose used to make fun of me about it, because she found out.

GAYHEART: I did not have that piece of Julie trivia.

GREER: No.

GAYHEART: And I’m truly impressed.

BENZ: Listen, I got the senior superlative. And let me tell you, it did not change my life. It meant nothing.

GREER: That can’t be true. Please, tell me it’s not true. I always think about how my life would be different if there were Brazilian blow drys when I was in high school.

KATZ: We were talking about the correlation between punk, and I think there’s a line to be drawn between budget and the idea of the scrappiness that you all had when making this film. And I’m wondering, do you think this film would be the same if it were made with a bigger budget?

STEIN: No, I don’t think so. Well, we shot in 28 days, with a $3 million budget. Which is nothing for a quote-unquote “studio film.” Also, everyone in Hollywood passed on this. The studio who made this was the home video division of Sony. It wasn’t like big Columbia, or big TriStar. It was Columbia TriStar Home Video, which later became Screen Gems. It was the success of Jawbreaker that launched a studio. It was the first film that was made, but I think it kept it scrappy and kept it frosty in a way. We literally had to shoot this entire film in 28 days.

BENZ: And we filmed it in Los Angeles.

GREER: Yeah, you never do that anymore.

STEIN: That was fun.

GAYHEART: I mean, we always used to work in L.A. What happened?

KATZ: It’s interesting, someone outside of the industry, you might expect with the success of this film in the ensuing years, that other people might take note and say, “We don’t need these gigantic budgets. The scrappiness actually produces better art, more resonant, lasting art.” And yet, that doesn’t seem to be the lesson that’s learned by Hollywood. Where do you think the wires got crossed?

GREER: Because it’s starring women.

GAYHEART: There you go. That’s actually true.

BENZ: Like, we’re not in superhero suits.

STEIN: And, it’s written and directed by a gay man. And there was a gay executive.

STEIN: So it’s like, it all was an aesthetic.

GAYHEART: And none of us were superstars, Darren. You found us. We were all working actors, but none of us were successful at the time. Except, maybe Rose?

BENZ: Rose had, yeah.

STEIN: The executive was like, “If you can get A, B, or C actress, we’ll finance this at three million.” And it was like Kate Winslet, Natalie Portman and Rose McGowan. I mean, Rose only made it onto that list because the executive was queer, and understood her magic in a way that maybe another executive might not have. I don’t know. Maybe I’m wrong.

GAYHEART: Well, I remember I wanted to be in the movie very badly. I came in and read for a lot of different roles. Do you remember that?

STEIN: Mm-hmm. Well, I remember who you replaced, but I don’t want to gossip.

BENZ: Yeah. Because Rose and I did a test with somebody. It was completely the wrong energy.

STEIN: But she’s a great actress.

BENZ: It was great, but she was just the wrong energy. She didn’t understand the comedic timing.

STEIN: Right, the heightened quality.

BENZ: And the rhythm of the dialogue. I think that actually bonded Rose and I, because I think we both felt it. And we were just like, “Oh my god.”

GAYHEART: But, my point of bringing that up was that it was, I felt that you, Darren, knew exactly what you were looking for. In everything. In the clothes, in the extras, in whoever was playing Julie, Courtney, and Vylette. You knew exactly every detail of this movie. You had a vision in your head, and it was so strong that you were able to translate it onto film. Some directors are not able to do that as well. That’s a huge talent, taking a vision and being able to translate it to film.

KATZ: I’d love to ask about your favorite lines from the film. Again, having just re-watched it, it was staggering. Obviously, there’s the slew of repeated quotes, but there are so many nuggets throughout the film of incredibly, to use 2024 parlance, meme-able lines. What are some of your favorite lines?

BENZ: I love when we’re literally carrying probably the lightest actress that they could hire, Charlotte. And when we throw her on the bed and I say, “That is no 105 pounds.”

GREER: Love that.

BENZ: It doesn’t matter that we killed her, it’s that she lied about her weight.

STEIN: That line comes from my mom’s obsession with working out and dieting. She weighed herself every day, so I was like, “Oh, I knew all about this.”

GREER: So does Jackie Kennedy. You can tell your Mom that.

GAYHEART: Does your mom know, Darren, that you noticed that about her?

STEIN: I’m sure she does. I think gay kids notice everything about their moms. I mean, any kid does, but especially gay kids.

KATZ: What about for you, Judy?

GREER: It’s, “She’s so evil, and she’s only in high school”?

STEIN: That’s a good one.

GREER: I’ve been asked that question, about Jawbreaker, and that line always comes up. I love it.

KATZ: Darren, how about you?

STEIN: Probably one of the more perverse lines, “The very picture of teenage perfection, obliterated by perversion.” I really like that, because it’s so bizarre, and it shows you immediately that this character is so diabolical. It’s funny, because people are like, “Well, where’s Courtney’s parents? What’s her home life like?” I was like, “It’s not really about that.” I mean, she’s simply Satan in heels. Like maybe she lived alone and there were robots controlling her–

GAYHEART: The parents are propped up in the basement, guys.

GREER: They’re dead.

GAYHEART: They’re gone.

GREER: She killed them.

GAYHEART: No parents.

GREER: The parents in this movie are in some ways like the Charlie Brown parents, where they’re like, “Wah, wah, wah, wah.”

KATZ: So, I’d love to explore the idea of camp. It’s interesting because the younger generation ascribes that label to just about anything these days, and in doing so, really dilutes the meaning of camp. And yet, when I re-watched this film, from one the very first frames, I was like, “This is camp. Unequivocally, unabashedly, this is camp.” If I were to show someone how to define camp, I would use Jawbreaker as an example. I’m wondering from all of your perspectives, if you see it that way, and if so, what is the quality that makes this film camp?

STEIN: I can tell you, for myself, growing up feeling different, feeling other, not feeling like part of the world. The movies that resonated for me were Mommy Dearest, Female Trouble, Xanadu, Grease. Oh and Valley of the Dolls and Faster Pussycat, Kill Kill. They were just these larger than life visions of the world. I think when you’re not included in a normal environment, maybe you relate to things that are beyond normal. Like, why else was I so enamored with Frank-N-Furter from Rocky Horror, or Divine from Pink Flamingos? Or Faye Dunaway as Joan Crawford in Mommy Dearest? A lot of queer people are. That aesthetic was sort of baked in me.

BENZ: I think it’s the inherent rhythm in the dialogue, and the vocabulary. I knew when I read this script, it was a heightened film. And it was reflected in all elements of production from the wardrobe to the production design, everything. There was that extra little spin on the ball, but I think it came from this script. We’re sitting here and we all still have our favorite lines. It just reminds me of just how rich the script was, how rich the words that Darren chose to put on paper. It was just a heightened way of speaking. It’s almost like Shakespearean.

STEIN: Well, I was trying to emulate Heathers, or Clueless. Heathers created a new language. I remember when I saw that film, it was like reading Catcher in the Rye. I aspired to that, in a way.

KATZ: How about you Judy? What are your thoughts on that?

GREER: I feel like I can talk more about punk rock than I can camp. I probably didn’t know what camp meant, or what it was, when we made this movie. I knew I loved Heathers, and you had talked to me about Heathers, and so I had that in my mind. But I was a very idealistic, recent theater school graduate. It was like, “I am taking this very seriously,” which I guess translated to camp.

STEIN: Yeah, no.

GREER: But I wonder about kids today, not understanding camp. I think that they don’t, but I don’t really know why. It’s sort of like a literature that they just don’t teach in school anymore.

KATZ: Let’s talk about the world of the film, which I think we’ve been circling about for quite some time. Darren, you told Vice that you wanted the film to quote, “Deliver iconic looks,” which is the tall order, that effort toward iconography. But you also gave this important nugget saying, quote, “Everyone’s like, ‘It’s so ’90s,’ but it’s not. If it were, the fashion wouldn’t be iconic.” So I’m wondering what role did you all have in collaborating with Vikki Barrett on the costumes, and creating the looks and feels of the aesthetic of the film, which I think is as “iconic”, to borrow the phrase, as the dialogue and as the plot of this film?

BENZ: I mean, I demanded to wear that Jessica McClintock prom dress that didn’t fit. It was one size too small, and it kept tearing open. But to me, it was the ultimate prom dress. If you were going to go to prom, that was the dress. But other than that, I just remember, I had so much fun in the wardrobe fittings with Vikki. Her attention to detail is so specific. It was still my most fun wardrobe fitting to date, just for all the looks and all the clothes for the movie, it was so fantastic. I wish I had kept everything that I wore, because I’d be wearing it today.

GAYHEART: I think Vikki was a true collaborator. She had her ideas of what our characters should look like, and what we should wear, and our color schemes, and all the things. But she really was kind, in that she let us have a little input, and we could make it our own. She was very sensitive to that. And I think that’s why it really worked, because we did feel comfortable. When she first showed me these pantyhose with the line, the seam. I think that’s from the ’50s, maybe, with a seam going down the back. I was like, “Pantyhose? We’re going to wear pantyhose?” But she taught me to see why that detail was important, and how meaningful that was. She was a real collaborator, and I appreciated her for that. Because I wasn’t as with it as I should have been.

GREER: I just had such a huge makeover in the movie. That it was really fun to go from Fern to Vylette, for obvious reasons. I would have worn anything Vikki told me to wear, and she had such specific stuff pulled. And there were two things that stand out to me. First, the bitch T-shirt with the rhinestones set. When I was sitting on top of the Corvette, I could feel the rhinestones rubbing on the paint of the car, and it was giving me a lot of anxiety. I was like, “I’m fucking up this car with these rhinestones.” And then the second thing that really stands out were the set shoes. We’re wearing high heels in the movie, but she bought me these velvet slippers in Chinatown that had all these embellishments on them. And she was like, “These are your set shoes, so when your feet hurt, you can put these on between scenes.” And I was like, “This fucking woman even gives us cool set shoes.” Even down to understanding how that plays into our vibe on set, even just our set shoes, were specific and cool and bedazzled and fabulous.

GAYHEART: I had a version of those, and I loved them, and I thought the same thing. I was like, “She has the coolest set shoes.”

KATZ: Darren, if you were to place one costume in the Smithsonian, in perpetuity, is there a costume for you that comes to mind?

STEIN: That’s so tough. I mean, the Vylette look in the bathroom, when Courtney throws her into the mirror. It’s hot pink. That was like Liberace meets disco diva.

GREER: Angelyne! Remember Angelyne?

STEIN: Yeah, Angelyne is a huge reference.

KATZ: Rebecca, you told Vice that, quote, “We all spent an enormous amount of time together, and really gelled, and really hung out. And really had a dialogue, and conversations. That’s different. You don’t always get that on a movie set.” And I’m wondering if you can expound on that, trying to get at what made the making of this film different.

GAYHEART: Well, listen, it’s 25 years later, and I have vivid memories of conversations that happened in the hair and makeup trailer. Darren, us hanging out in the trailer, getting our hair done. We were all of a certain age, and we were shooting this movie really fast. We were together for, how many days?

GREER: 28 days, with one day off a week.

BENZ: I remember I would go home to my fiance, at the time, and I would go home after shooting. And I’d be still in Marcie energy, talking like that and he would be like, “What?!”

GAYHEART: We were just young, having fun, and we were all very committed to this movie, and this material. And that was the bond that we all had, was that for whatever reason, each of us had our own reasons for loving this script and wanting to do it. But I think we were also committed, and we really wanted to make it great.

STEIN: We wanted to make a good movie. And I think, because it’s a high school movie, obviously it’s hard work, but you want it to feel like high school. Like, “Oh, we’re all having fun. It’s a fun collaboration. We’re all enjoying this process.”

GREER: Yeah, it was really a good experience.

STEIN: In good and bad ways. Like for example, when Judy was Fern, people were super nice to her on the set, and when she was Vylette, they were not as nice. Or whatever. Or, Rose felt like you were bitchy when you were Vylette, and you guys would be at each other’s throats more. So I just love that life imitated art, and vice versa.

GAYHEART: There were so many dynamics on the set.

STEIN: No, those are so important. But dynamics, like I remember telling you, “Blow the smoke in her face.” And you were like, “Okay.” And I didn’t tell Rose you were going to do that.

GREER: Oh, yeah.

STEIN: And I remember telling Rose, “Well, listen, if the glass doesn’t crack, throw her again against the glass. Because we need that to crack.” And we only had two fake mirrors to use, because of the budget. And then when you blow the smoke in her face, she takes the cigarette out of your mouth and throws it on the ground.

GREER: Yeah.

STEIN: That was all improvised.

GREER: Yeah, she was pissed.

GAYHEART: She was pissed. I remember that day.

GREER: That was the worst day.

GAYHEART: Well, there were some other days, but…

GREER: There was one other really bad day.

GAYHEART: Was there really?

KATZ: Let me attempt to ask something in that space. Darren, you once said, “Whenever you have three girls, and they’re playing the three bitches of the school, and they’re shooting film in a compressed four weeks to shoot a movie, that tone affects the dynamics of the girls.” And I’m wondering if anyone could speak to that, with both 25 years of perspective, and a Hollywood landscape that’s seemingly, more intentional about not forcing women to be pitted against one another? I’m wondering if anyone has any thoughts around that, in looking back on it?

GREER: That’s a good question.

GAYHEART: Listen, I think if we were to do this now, it would be a very different vibe because, you’re right, women are supporting women. There’s not so much of that fierce, competitive, whatever. And I think if we had to do it over now, it would be similar in many ways, and it would be different in a few ways.

BENZ: I think, because it was such an intense shoot, and because we were working six days a week, and it was that intense high school bubble. That the dynamics of the characters, like Darren was saying, fell over into the dynamics between us. And our relationship as the characters kind of overflowed into our off set relationship, on set.

KATZ: I want to thank you all, so very much. This has been a true honor, and I just want to say to close out, how special it is to have a film that holds up this remarkably, that’s something that people still want to talk about and think about critically. That’s a really special thing, and it’s because of all of you, and especially Darren at the helm.