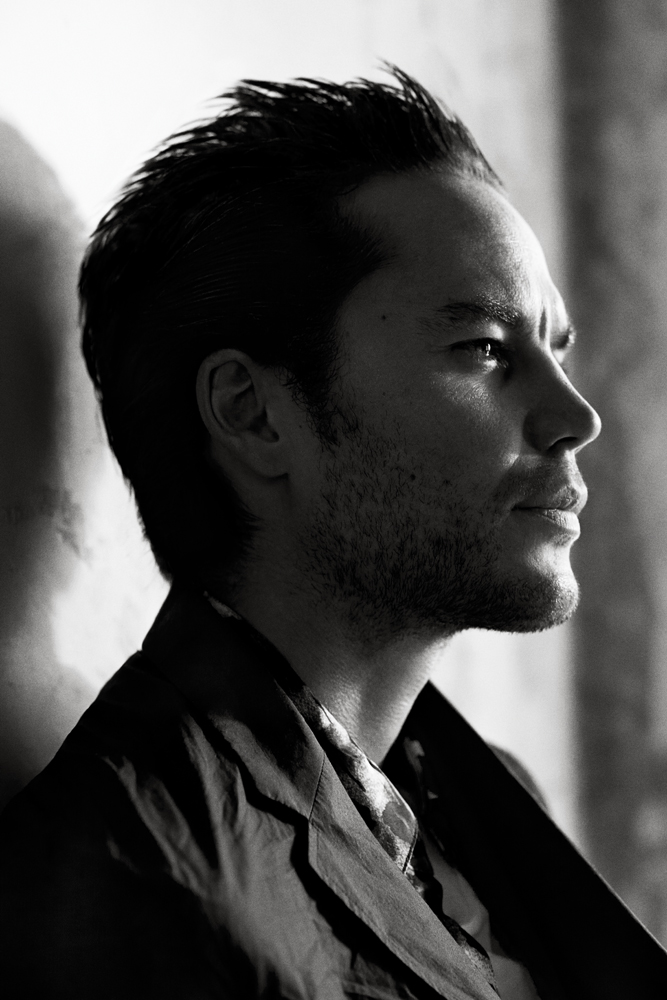

Taylor Kitsch

I’m never going to be like, ‘Oh, this attention from women sucks.’ It’s flattering 99 percent of the time. Taylor Kitsch

When I told a female friend I’d be interviewing Taylor Kitsch, the actor who broke out as the hard-nosed, brooding fullback Tim Riggins for five seasons on NBC’s Texas high school football melodrama Friday Night Lights, her jaw actually dropped. Kitsch’s rugged looks—he’s a former model and junior hockey player—and world-weary onscreen demeanor often have this effect on women; another friend referred to him as a “classic hunk.” But the 32-year-old British Columbia native possesses a surprising absence of vanity. Kitsch bought a home in Austin while filming FNL, and still lives there, ducking the Hollywood spotlight as much as possible. When I met up with him in New York, he wore a T-shirt and jeans to a luxury hotel lounge and asked if I was planning to “get some grub.” He’s remarkably grounded, with a ready laugh and a tendency to pepper his speech with the word fuckin’. The lack of pretense shows in his latest effort, the gritty drama Lone Survivor, which happens to be Kitsch’s third collaboration with director Peter Berg (after FNL and the big-budget action pic Battleship, 2012). Based on former Navy SEAL Marcus Luttrell’s nonfiction book, the film, which co-stars Mark Wahlberg, Eric Bana, Emile Hirsch, Ben Foster, and Alexander Ludwig—depicts a botched 2005 mission in Afghanistan. Kitsch plays Lieutenant Michael Murphy, one of four SEALs drastically outnumbered by Taliban forces. The protracted gunfight at the center of the movie is unsparing, graphic, and hyper-realistic, but Lone Survivor surrounds it with moments of unsentimental tenderness among its band of brothers.

Lest you think Kitsch is only interested in stoic roles as athletes and soldiers (he was also a Civil War veteran transported to Mars in 2012’s John Carter), he’s subverting his image with upcoming turns as a gay activist in a TV-movie adaptation of the 1985 Larry Kramer play The Normal Heart, and as a doctor in the Canadian comedy The Grand Seduction. And he recently wrote, directed, and produced a half-hour short about small-time criminals, Pieces, which he’s planning to adapt into a feature. I sat down with Kitsch to talk about the movie, his time spent sleeping on subways in New York and in his car in Los Angeles, and, inevitably, how he reacts to his female admirers. (To my awestruck friend and other aspirants: he’s single—but read on for how not to approach him.)

TEDDY WAYNE: I didn’t really know the story behind Lone Survivor. What, other than Peter Berg’s involvement, drew you to it?

TAYLOR KITSCH: There’s not a day that goes by that you don’t think about it, really. [Marcus] Luttrell’s become a great friend of mine now, and I was talking to him about it. It’s not even the responsibility of just the performance or just the memory of Murph being part of the SEAL community—this is a torch I have for the rest of my life. How often in this gig do we get to have that, and want it? You didn’t know of the book or the story, and now you’re going to think of my performance when you think of Mike Murphy, and that’s an incredible responsibility.

WAYNE: How much of that is solely inspired by the real figure and how much of the work is purely fictional?

KITSCH: I think so much of it is that it actually happened, that these guys are still out there doing it. When you meet guys who were buds with Murph, guys that fought right next to him, you really do see how much it means to them that the film’s done right. You have that opportunity to be like, “Okay, let’s see what I’m fucking made of here, let’s see what I am capable of doing,” and training to do it.

I kind of become super-myopic with work and kind of shut everything else out, and I don’t know anything different because that’s what’s gotten me this far …Taylor Kitsch

WAYNE: So what was the training?

KITSCH: There’s a workout called the Murphy that he created when he was in the SEALs. It’s, like, a mile run and then a hundred pull-ups, 200 push-ups, 300 sit-ups, then another mile run, with a 40- to 50-pound weighted vest. Some guy claims to have done it in under 30 minutes. I couldn’t get there. I was under 35, which is a fucking insane time. I was in the best shape of my life.

WAYNE: How about the weapons training?

KITSCH: We went to Albuquerque. We had guys who had fought with Luttrell to teach us the weapons systems. And that’s live fire; it’s not like standing there and just shooting at a target. They call it bounding, and all these other things these guys do as a team, and they’re fighting together as a team. Murph was the leader of the guys, so he’s making the call, and you really do see it kind of seamlessly in the film. When he makes a call of “peel right” or “peel left” or “get on line,” it’s those things that the SEALs fucking love. We got the technical part of it.

WAYNE: Was there any improv?

KITSCH: Absolutely. Some of the funnier stuff—when I’m in the hide with Mark [Wahlberg] talking about a girl and a Coldplay concert, that was roughly scripted and we just went with it, and Mark is fucking on it. That guy has endless energy, he’s quick. Pete would call cut, and the whole crew would burst out laughing. Or we would even have a bit of a camera shake because the camera guy’s dying, you know?

WAYNE: You were a junior hockey player in Canada before you injured your knee at age 20. Do you feel like you were on the path to professional hockey?

KITSCH: Yeah, at least semi. I was hopefully going to go on a scholarship and turn pro. If I even scratched the lineup, it would’ve been fourth line, up and down from the minors, but, I mean, a minor career was a dream as well.

WAYNE: When that injury happened, was it clearly career ending?

KITSCH: In retrospect I think it was career ending. But at the time, it was that denial of, “Fuck it, I’m gonna recoup it.” But then I recouped it, and my first game back it blew out again.

WAYNE: So what were you thinking in terms of life plans?

KITSCH: Oh, it’s over. I was devastated. It really is close to art simulating life in the sense of what FNL was—if you wreck your knee, that’s it, everything is gone. Obviously it’s not; it’s a blessing in disguise, but at the time I remember my best friend came and took me off the ice and I was a wreck. My mom was in the stands and she was a mess, and then I was in the dressing room and I refused to take my gear off. I just knew the second time I did it—like, buddy, uh-oh.

WAYNE: So did you do any acting by that age?

KITSCH: I loved it. I always grew up winning all these public-speaking competitions in school.

WAYNE: Did you move to New York soon after the injury?

KITSCH: Yeah, at 21.

WAYNE: I read that you were, at points, homeless and sleeping on subways—is that true?

I’m going to keep swinging for the fences. I’m not going to go play another Riggins—that’s done. Taylor Kitsch

KITSCH: It’s true. Only for a couple weeks. It wasn’t like I was walking around with a grocery cart. I didn’t have a visa; I couldn’t get fucking work. I wish I could’ve waited tables. I was taking classes for free with my acting coach, Sheila Gray—she’s been amazing, and so I finally paid her back after the first movie I did—and then I just ran out of money. I was staying at my best friend’s place. He sublet a bedroom in a big family house, and I was sleeping on his floor, and then I wore that out, and I leased a place up on 181st Street in Washington Heights, pretty fucking sketchy area, and I couldn’t get electricity because, one, no money, and two, I had no Social Security. So from that best friend, I would take his girlfriend’s blow-up mattress and use candles. And then that wore out, got kicked out of there, and I would go back to my buddy’s place, and at midnight or whenever, he wanted to go to bed, I’d be like, “All right, I’m gonna go stay at”—make up somebody’s place—or a gal’s place or whatever, and then that ran out. [laughs] Quite literally. And then I’d sleep on the subway until 5:30, 6 in the morning, and I’d go to the gym and work out for god knows how long and have a shower and just loiter.

WAYNE: And you were also a model at this point?

KITSCH: Yeah, but I was completely out of work. Didn’t work, really. And I was living in a spot that they give you, and by the time you get a job, you owe them so much back end that you’re in debt anyway, so then I left that because that was just stupid to just keep building debt.

WAYNE: What was your first big break?

KITSCH: While I was homeless, I met my manager through one of the guys at the modeling agency. She’s like, “Yeah, I’ll take a meeting, whatever,” just being nice to him. So I had a meeting, and 10 minutes in, she’s like, “Okay, I’ll take you on.” Then my first reading—still homeless—I got but I couldn’t do because I didn’t have a fucking visa again. So I stayed and studied more and then I moved away to Barbados to work with my dad and dig ditches, and that was the most time I ever spent with my dad in my life on a one-time basis. I made, like, 6K. Then I bought a little—it’s called a Firefly or a Chevy Sprint, which is like a 12-inch wheel hatchback car that goes on fumes. It’ll go forever, and so I bought that when I got to Vancouver—moved back-moved down to L.A., sublet a room for two months. That money ran out, and then I lived in my car.

WAYNE: So you had two homeless stints. And both times you picked the transportation choice of the city you were in—subway in New York, car in L.A.

KITSCH: Yeah, that’s a good point.

WAYNE: You need to be in a seaside place for a while and live a few months in your boat.

KITSCH: I know! I was super-angry one day in L.A.—my car’s a piece of shit, and then the front window wouldn’t go down, and so I’m screaming at the handle, forcing it down, the window shatters, and it’s the bigger one, ’cause it’s a hatchback. So now I’m fucking homeless and I got a clear plastic bag with duct tape. So I stayed over at my best friend Josh Pence’s place, and I’m like, “I think I’m gonna go home,” and his mom overheard it, and she’s like, “You’re not fucking driving 23 hours to Vancouver with a plastic bag,” and so I went to the junkyard and got it replaced for, like, $75.

WAYNE: I thought she was going to say, “No, you should stay here and fulfill your dreams,” but she was just making sure you got a new window.

KITSCH: [laughs] Yeah! When you’re doing it, it’s not like, “Oh, man, I’m really paying the price.” You just did it. I’d go to Trader Joe’s and get a big thing of cottage cheese and brown rice cakes, like, four bucks—that’s all I’d eat. And I’m a nutritionist, so I’m like, that’s probably the best bang for my buck. I’ve got protein, carbs …

WAYNE: You start doing the protein-price ratio. Split pea soup is good for that, too.

KITSCH: Yeah, garbanzo beans—

WAYNE: Tuna fish.

KITSCH: Yeah, the cans, that was New York. The Sunkist cans?

WAYNE: StarKist, right? But it should be Sunkist—just drinking Sunkist orange soda all day long.

KITSCH: [laughs] Yeah, have diabetes at 25. So she gave me the money, I got the thing, drove from three in the morning till midnight, straight. Back at home with mom, and then my first or second reading was Snakes on a Plane [2006]. Got it. And then The Covenant [2006] and then Friday Night Lights.

WAYNE: In the first few episodes of FNL, Riggins seems to be a secondary character.

KITSCH: He was. I was told he wasn’t gonna last.

WAYNE: What happened? People started responding to you?

KITSCH: Yeah, I guess. Whatever it was, people clicked to him, and the studio loved him and what we were doing with him.

WAYNE: Most of the humor comes from Riggins’s off-the-cuff moments.

KITSCH: Yeah, the dry humor that Riggins has—that’s mostly improv. I played hockey my whole life. I was just hanging out with a bunch of pro-hockey players who were good friends. Calling everybody six, seven, two, zero—that’s Riggins. Calling that whole apology on the field, all of it was made up on the day of.

WAYNE: You mentioned digging ditches with your father was the most time you ever spent one-on-one. You were raised by your mom for the most part?

KITSCH: Yeah, for the most part, with my two bros. I’d see my dad every Christmas for the most part growing up, but he left when I was one-ish, and then I’d spend a couple weeks over Christmas with him. I remember going fishing with him; I remember snowmobiling. I remember him carrying me around on the ice because he played hockey growing up, too. I remember those flashes, and I don’t know if it’s made up in my head—but I do remember blips, and being super-pumped that he’s letting me, at 6 years old, rip on the open lake in the snowmobile.

Growing up, I was that guy at school getting kicked out of class every day to make someone laugh. Voted funniest guy in the school twice.Taylor Kitsch

WAYNE: Riggins didn’t have a father around. Not to get too precious about it, but did that inform the role?

KITSCH: Absolutely. I had no doubts when I was going to play it. It just felt super-organic.

WAYNE: Do you see your dad more often these days?

KITSCH: No, maybe once or twice a year. Not even. I haven’t seen him in years. I’ve stayed in contact via e-mail, but I don’t reach out as much as I should, I guess, but I don’t have that—this may gut him, but I don’t have that … where I’m like, “I want to know what’s going on,” or “Why did you …” My brothers and I talk about it a lot but—and sometimes it’s joking, you know, but … I think it’s affected them more, especially one of them a bit more, just because he was older—he was 8. And my mom was with an older guy, and he was a super-sensitive man, and he connected more with me than either of my two brothers. So I think I got a lot of that sensitive part that allows me to be that kind of actor through him. My mom and he split up when I was 12, and I was a fucking wreck and I wanted to go live with him, and then I would still go spend weekends—neither of my brothers would, but I’d go spend a weekend with him as much as I could. And he was getting older, and I was not conscious of that either, and then my mom told me he’d died not long ago—man, and it was shitty that I couldn’t have reconnected before he did, because it had been five, six, seven years from the last time I saw him. And he was just the softest soul.

WAYNE: You live in Austin now. What were your thoughts when you first got there for filming FNL?

KITSCH: I didn’t even know where Austin was. Quite literally, I’m like, “We’re going where to shoot this fucking thing?”

WAYNE: You thought it was Boston? “Massachusetts Forever.”

KITSCH: [laughs] Yeah, totally! Which doesn’t have the same kind of tone, does it? And Austin was like nothing what it is now. It’s, like, the fastest-growing city in the U.S. now. But I bought a place end of second season, and that’s my place now, just a little 1,000-square-foot condo.

WAYNE: What’s your life like there?

KITSCH: I golf a lot. I’m in a men’s hockey league. I’ve made some great friends there. I’m on my motorcycle a lot. Kyle Chandler [of Friday Night Lights] lives there, so whenever we can make time, we’ll go on these long rides together. Had a great gal there. Southern belle.

WAYNE: “Had,” you said?

KITSCH: Yeah, it’s been tough lately. You never know how it’s going to turn out. But I was with her for years.

WAYNE: And she was from Austin herself?

KITSCH: From Corpus [Christi].

WAYNE: How did you meet her?

KITSCH: Through my stunt double. He’s like, “You gotta meet this gal; she’s ridiculous active.” She’s a yoga instructor now, but she wasn’t when we met. But just a super-sporty Southern belle, you know? Great.

WAYNE: I don’t want to embarrass you, but I told a female friend I was interviewing you, and she was momentarily stunned. I feel like male actors don’t often discuss this, but does it ever get almost boring, or do you ever feel objectified if women respond this way? I mean, it’s a good problem to have, but is there ever a point where it’s like, be careful what you wish for?

KITSCH: You’re conscious of it. I mean, I’m never going to be like, “Oh, this attention from women sucks.” It’s flattering 99 percent of the time. After the premiere screening in L.A., there was a young woman, beautiful, mid- to late-twenties, and you’re pretty crushed after this movie, it hits you hard, and I was talking to a guy who had served. All of a sudden this girl comes up and she’s like, “Hey, I just gotta say, this movie was this-and-that, but that fucking scene of you walking down the hall [in which Kitsch is shirtless] …” And then it inevitably went to, “What are you doing later tonight? Can I give you my number?” I kind of took offense to it. That’s the one shitty experience out of it, but it’s still flattering. Out of everything in that fucking movie, that’s what you took?

WAYNE: Is dating a non-actor much more appealing to you?

KITSCH: Absolutely. I mean, it’s hard because you’re all in or I’m all in, and I become super-myopic with work and kind of shut everything else out, and I don’t know anything different because that’s what’s gotten me this far, so I live a pretty unbalanced life. And it’s tough because the gal can’t really relate in that sense. It doesn’t mean she’s not supportive, but that part of it wasn’t relatable. She didn’t understand, “Oh, okay, this guy’s gonna be off the grid basically for whatever it is.”

WAYNE: That’d be tough no matter what.

KITSCH: Yeah, it is, but if you’re dealing or dating another actress or whatever who goes through that same process, then maybe they might have a bit more acknowledgement of it.

WAYNE: But you seem pretty divorced from the Hollywood scene. You’re not tabloid fodder that much. How do you safeguard your privacy?

KITSCH: Austin helps. No Facebook. If anyone ever thinks I’m on Facebook or Twitter, it’s not me, for the record—it’s never me.

WAYNE: But you are on MySpace, right?

KITSCH: [laughs] Totally.

WAYNE: It sounds like you’ve preserved your lifestyle pre-acting, pre-fame as much as possible.

KITSCH: I try. When I’m in L.A., I’m with one of my best friends, who’s an actor coming up, and it’s good to have that dialogue. In Austin I don’t have that a lot. So that’s one of the downfalls of being in Austin, if there is one, that I don’t have another couple artists to bounce shit off. It’s great to decompress, but it’s tough because it goes from a hundred miles an hour living this fucked-up lifestyle to you’re in your apartment, dead silence, and you’re like, “Oh, what do I do today?” I guess I go for a coffee by myself and just read a couple scripts or something.

WAYNE: You’re doing a couple different movies this year—The Normal Heart, The Grand Seduction. Far different from Battleship and John Carter. These are more in an indie direction.

KITSCH: I was always on that track, from The Bang Bang Club [2011], which is one of my proudest things I’ve ever done in my life. And that’s kind of my personality, too. I’m going to keep swinging for the fences. I’m not going to go play another Riggins—that’s done. I can go and now try and disappear into Normal Heart. I was just talking to Ryan Murphy about it, the director, who took a fucking leap of faith with me to go and play this, another true story—that’s a bigger risk than what John Carter was, because if you don’t go in there and nail that role, this could be a fucking career-ender.

WAYNE: Do you have any ambitions beyond acting?

KITSCH: I wrote and directed a short [Pieces] that Oliver [Stone, who directed 2012’s Savages] has seen, that Berg has seen, that [John Carter director Andrew] Stanton has seen, all the producers of John Carter have seen, and I just got two to four million bucks to make it into a feature. So I’m going to hopefully write it in January, February. Pete’s mad for it, and Pete will tell you—man, he’ll fucking rip it in half—but he’s been incredibly supportive, so hopefully, I’ll go shoot that in Detroit and Texas.

WAYNE: Can you see yourself transitioning at some point to someone who directs, like Peter Berg did?

KITSCH: Absolutely. I’d be fucking stupid not to be taking notes from a Stone or a Berg. The way I direct is open. I want to empower you as an actor, and when you’re not on track, I’ll tell you, but when you are, I want you to fucking just go with it. And so I cast Derek Phillips, who played my brother in Friday Night Lights—he’s unrecognizable in the film. And then my best friend in L.A. [Josh Pence], whose mom gave me money for the window, he plays the other guy in the short.

WAYNE: Would you ever do an over-the-top comedic role?

KITSCH: I’d love to, it’s just got to be the right one. When I work, I take it super-seriously, but when you get to know me, man, I’m not‚ I laugh as much as possible. Growing up, I was that guy at school getting kicked out of class every day to make someone laugh. Voted funniest guy in the school twice.

WAYNE: Just twice? What happened the other times—you finished second?

KITSCH: [laughs] Yeah, totally! Last. The jokes didn’t hit that year. I was off.

TEDDY WAYNE IS A NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, AND AUTHOR OF THE ACCLAIMED NOVEL THE LOVE SONG OF JONNY VALENTINE. HE RECENTLY FINISHED HIS FIRST SCREENPLAY, THE INDIE DRAMEDY LIKABLE CHARACTERS AND IS WORKING ON HIS YET-TO-BE-TITLED THIRD NOVEL.