The Compulsive Satisfaction of Swallow

Exit Poll is a series exploring the good, bad, and outright deranged films and events our editors are attending. This week: Bessie Rubinstein heads to Swallow, a second feature film by director and writer Carlo Mirabella-Davis, inspired by his grandmother’s institutionalization. The Tribeca prizewinner is a refreshingly accurate portrait of compulsions and how they manifest, but is less thorough with its portrayal of generational trauma.

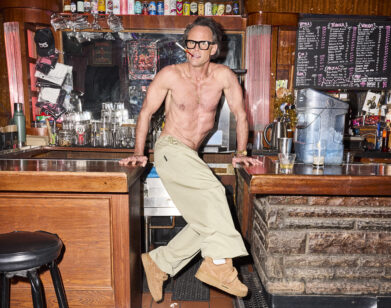

There’s a shot in Carlo Mirabella-Davis’s Swallow which spoke to me as a chronic nail-biter (not a cute quirky-nervous one, but a don’t-stop-til-you-see-blood one): protagonist Hunter (our past cover girl Haley Bennett), arms folded on the cheap bedspread before her, dreamily pulling handfuls of dirt, placing them in her mouth, and (of course) swallowing. Besides the pile of soil, the bedspread is untouched—Hunter sits on the floor—and the sleeves of her prim collared shirt are a remarkably unstained off-white. Soft, meditative music plays; the pleasure derived from the dirt seems of the same family as the satisfaction provided by dragging your feet through a patch of clean snow, or digging your teeth into a new growth of white nail: immediate satisfaction, immediate release. Minutes later, of course, Hunter is retching into the toilet and sweeping the dirt off the spread, just as I inevitably will fold my fingers under themselves so that the person sharing the subway pole with me won’t see my torn-up flesh. The shame always catches up.

Not so much in this film. Swallow is less interested in Hunter’s pica, an eating disorder in which control looks like consuming non-food objects, than what’s causing it: an utter lack of intimacy in her marriage combined with a paucity of hobbies, interests, friends, and family. Hunter is a child of assault whose mother saw her as nothing other than a physicalized representation of that assault, and this, together with Hunter’s own unwanted pregnancy, is more than could be resolved through years of therapy—much less a 90-minute feature.

Similarly to Hunter’s mother’s perception of her, Mirabella-Davis would be forced “Melancholic housewife” has a new look, and it’s Bennett, eyes flashing with loathing over wine-blotchy cheeks, watching her Chad of a husband choose his phone over her meticulously-prepared dinner. Without Bennett’s specific intensity, Hunter would simply be a human vessel of trauma, not unlike how her mother sees her. Considering that Swallow honors Mirabella-Davis’s grandmother, herself a homemaker who in the ‘40’s developed neuroses so extreme that she was subsequently institutionalized, the director was presumably loathe to create a reductive treatment of the woman on the verge. And so he leans into cookie-cutter-isms, relying on hallmarks disturbingly familiar since Henrik Ibsen’s 1879 play A Doll’s House, to tidily lock us into character types which are as banal as Hunter’s experience of her life. “I swear things are going to be different,” says Neglectful Husband (Austin Stowell); “I feel so lucky,” says Delusional, Unhappy Wife. Freed from the necessities of nuanced exposition, Swallow has time to raise an interesting aesthetic update to the stir-crazy domestic narrative with sense-inducing shots of endless glass walls and small, silky glass and metal objects, lined up like trophies after Hunter has dug them out of her feces. When the appearance of wealth we covet consists of not plentiful appliances but sleek surfaces, streamlined multifunctional furniture, and powdered foods, what is the new prescriptive for the disillusioned bride? Sleekness itself, perhaps: the crisp auditory crunches and cold shimmers of ice that call to mind an ASMR video. (“Oddly satisfying,” as Hunter puts it.) While Hunter disappears clutter into her mouth, becoming an ennui-laden machine of neatness, the film overlooks issues that are decidedly more messy. We may see the profound relief of the afflicted, but unfortunately, her disorder remains part and parcel, even a tool, of her liberation.