The subtle genius of Jon Brion’s Lady Bird soundtrack

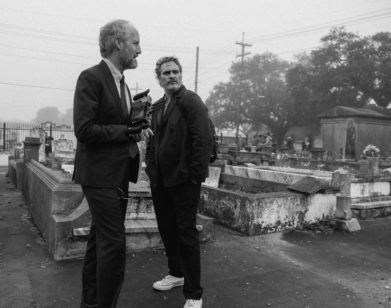

IMAGE COURTESY OF A24

Good film scores generally succeed in ways that other music doesn’t: when they’re almost unnoticeable, operating on the subconscious, pinpointing an emotional bullseye in the back of the brain. At their best, they can leave you in tears without you even knowing it. Just see Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird.

Composed by Jon Brion, Lady Bird’s soundtrack is, like the film itself, unafraid to inspire an earnest nostalgia. “Some filmmakers are very nervous if you put a feeling in, because there’s been this cliché over the last 20 years—they don’t want to be accused of leading the audience,” says Brion. “Whereas in my opinion, I think of it as a job requirement.”

Having also created the music for movies such as Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch-Drunk Love [2002] and Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind [2004], Brion is one of those film composers uniquely capable of cutting to the emotional quick of whatever it is he is soundtracking. Just take the song “Phone Call,” from the latter film. Brion’s washed-out, lo-fi guitar floods the listener with an emotional haze, the equivalent to falling perhaps mistakenly but nevertheless headlong in love with someone on the first date.

Brion explains that to do so, he watches whichever film he’s scoring once or twice a day for up to two weeks. “When I’m watching I get an overview of things I know I want to avoid, and things I know I want to amplify.” Relying on his subconscious reactions, he’ll play along in real-time to the film on mute. “When I find a feeling, or a tune, or set of tunes that can be played against the movie any time and feel real and part of its world, then I tend to know I’m on the right track,” he explains.

In Lady Bird, this takes the form of an evocative piano motif that repeats throughout the film—a certain descending scale that somehow manages to sum up high school in a few precise notes. Brion explains that he wrote it only the day after seeing the film for the first time, “just fresh off the feeling of seeing it.” Gerwig, he says, called the motif “the tumbling thing,” and took to it because, “it’s like that period of life where you’re tumbling around a bit.”

Despite “the tumbling thing’s” versatility, Brion went one step further and also devised a small counterpoint answer to the theme—a reversed, ascending scale—that he and Gerwig called “the falling-up part.” What better to match the film (and life), with its ebb and flow of optimism and pessimism, hope and despair? “You’re not just falling down,” he adds, “You’re falling up; you’re falling sideways.”

Lady Bird, helped along by Brion’s soundtrack, will make theater goers do their own sort of “tumbling thing”: falling up, down, sideways, and into a heartfelt high school vertigo.

LADY BIRD IS OUT IN THEATERS NOW.