director

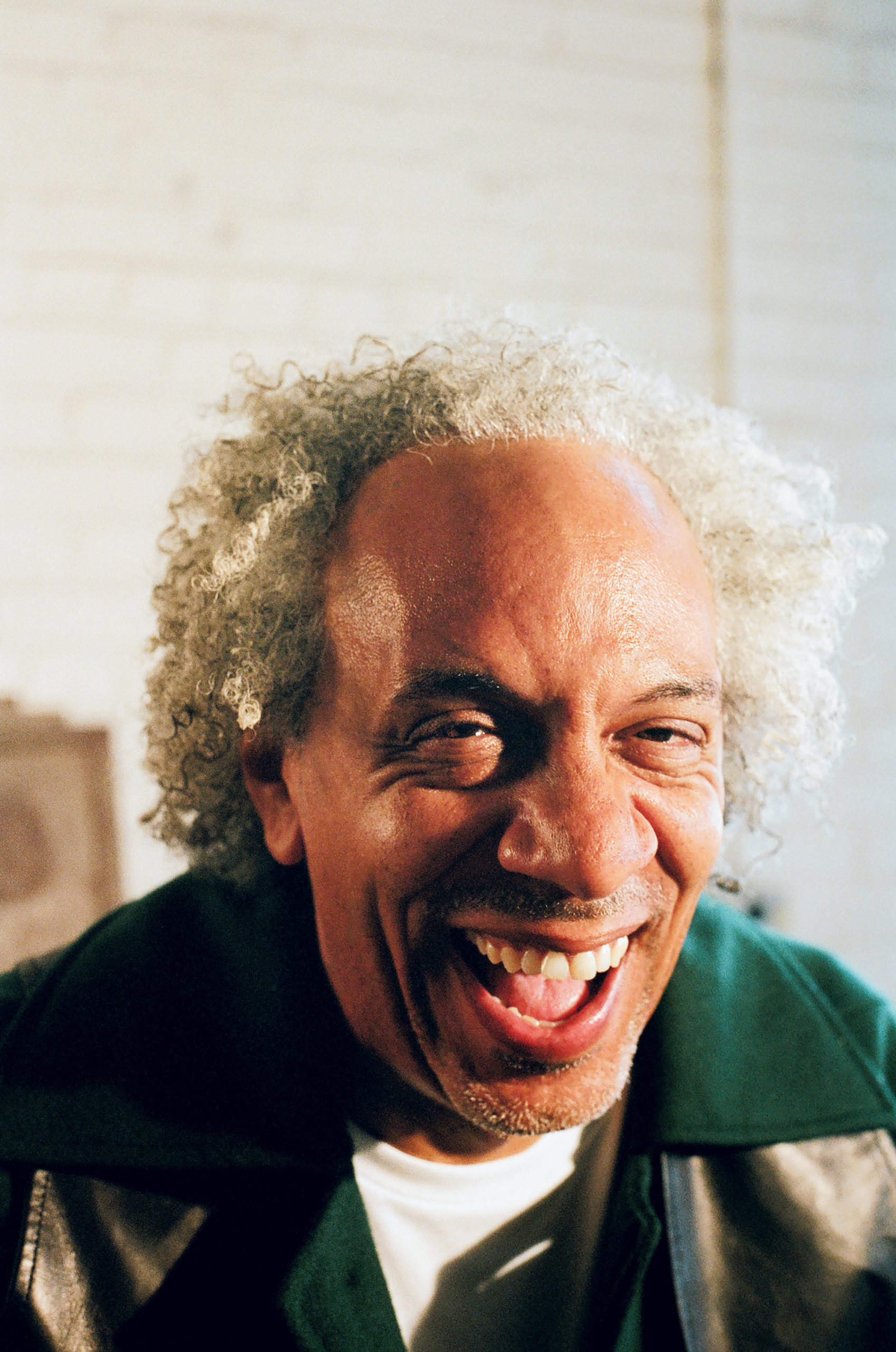

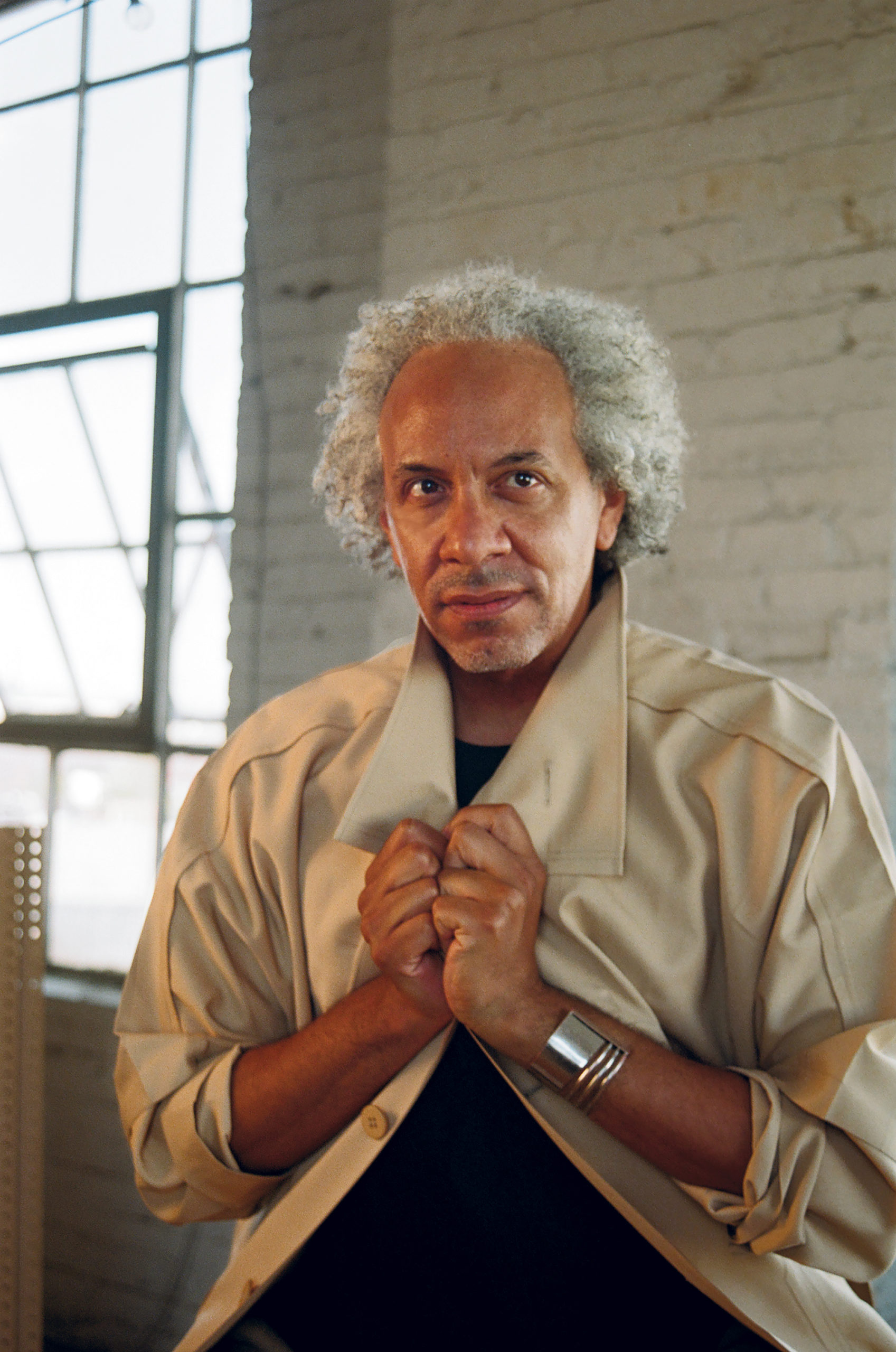

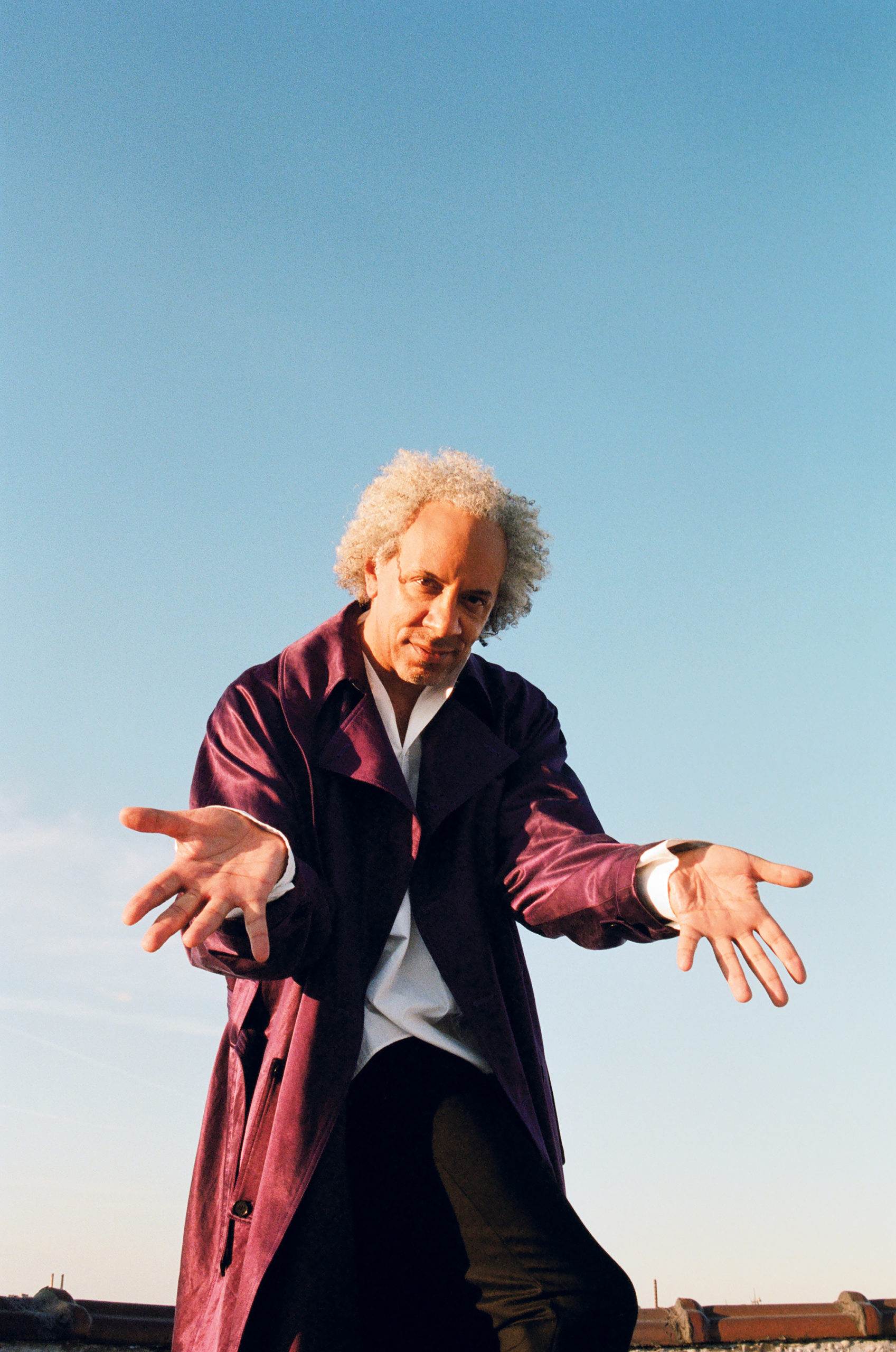

Stephen Winter and Lee Daniels Trade Tales of Breaking In and Breaking Out

Coat and Vest by Salvatore Ferragamo. T-shirt by CDLP.

“We are Black faggots with a political agenda. We are your worst nightmare.” Rarely has such a radical mission statement been articulated in the first 30 seconds of a film. It comes in the opening scene of Stephen Winter’s seminal indie classic, 1996’s Chocolate Babies, when five self-described “gay terrorists” confront an ineffectual New York City councilman about the lack of social services during the AIDS epidemic. Winter’s fierce, hilarious, raucous, loving, nonconformist valentine to queer bohemian life during the height of the AIDS crisis is like nothing that ever came before it—and, unfortunately, like very little since. A native of Chicago who moved to Manhattan to attend film school at NYU in the early ’90s, Winter shot Chocolate Babies over a dizzying three-week period, relying on friends as crew and using locations such as his own apartment, the Lesbian and Gay Community Center on West 13th Street as a stand-in for City Hall, and several Black-operated squats around the Bronx, Brookyn, and New Jersey. “People were very sweet and helpful about lending support to the film,” he recalls. “Making a film was a rare thing back then, especially one which intersected Black, queer, Asian, drag, trans, house music, and HIV.”

Winter shot the film on Fuji 16 millimeter, not only because it enhanced the richness of his candy-colored palette, but because “it was well known among Black filmmakers that Kodak film at the time sucked for shooting Black skin.” Chocolate Babies stands as a high-water mark of independent film, and Winter as a patron saint of experimental cinema, but its success didn’t guarantee the same turbo-rocketed career trajectory that many of Winter’s white male peers enjoyed. In fact, as Winter notes, the institutional racism of the film world at the time has forced so many talented Black directors to pivot into careers like producing, teaching, or the theater. Winter went on to produce the 2003 documentary Tarnation, among other projects. His second feature, 2015’s Jason and Shirley, is a fascinating reexamination of the exploitative relationship between a Black, gay man in front of the camera, and his white female director/ antagonist behind it, using Portrait of Jason, the iconic 1967 Shirley Clarke documentary about Jason Holliday, as its source material.

Maybe, finally, the world is catching on to Winter’s brilliance. He’s currently amping up production on his long-gestating biopic about the late disco-soul singer Sylvester. For this television series, he’s collaborating with his dear friend, the director and producer Lee Daniels, who knows quite a lot about the sweat and tears involved in getting a Black story projected onto the screen. This past June, Winter and Daniels talked about all the great Black talents you’ve never heard of, and all the ones that made a huge impact and should never be forgotten. —CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

STEPHEN WINTER: Hi, baby. How are you?

LEE DANIELS: Beautiful, now that I hear your scrumptious voice.

WINTER: I’m in Daytona Beach with an old friend and I’ve been seeing the sunrise and walking the beach every morning and completely decompressing. I’m having a glorious time.

DANIELS: I want your life. You go from Palm Springs with me last week, to Daytona Beach this week. That is the life of a very chic, very sophisticated, Black artiste.

WINTER: I’m Black and charmed.

DANIELS: So to start, tell me the films you loved as a kid.

WINTER: My father took me to see 2001: A Space Odyssey in 70-millimeter when I was about eight or nine, and it blew my roof off. That was when I first felt transported. And, you’re going to laugh, but I did see Mahogany on TV.

DANIELS: Why would you see it on TV? I remember seeing it in the theater.

WINTER: It was the ’80s and I was 10 or 11. My mother was a Jamaican diva, and Diana Ross is, of course, a Detroit diva. They resembled each other physically and they had a similar intensity. And I had never seen my mother represented in such a way: the glamour, the drama.

DANIELS: Do you mean Diana Ross’s character in Mahogany or Diana Ross, period?

WINTER: Diana Ross’s character in Mahogany. Something about the way she was struggling against the men and against expectations, and had this gay white guy running around. Everything about it was clicking in my prepubescent head. That’s my mom.

DANIELS: What brought you to wanting to make films?

WINTER: As soon as 2001 and Star Wars and all these other movies were in my head, I’ve wanted to make them. I would grab my father’s Super 8 camera and shoot little films. I would draw the posters with the credits of the lead actors on them and everything. There were films that really inspired me too, like Wizard of Oz and Black Orpheus, which is a controversial title at this point.

DANIELS: And a controversial film for a controversial queen like yourself to watch!

WINTER: My mother and father loved Black Orpheus. So when VHS happened, that was the first one they bought. Me, my brother, and my sister have probably seen Black Orpheus more than any other film, because it was always available. I can certainly look at it now and see there’s a preciousness there that’s almost disturbing. But at the time, the glamour, the gorgeousness, the island, the way the film moved like a dream—I was attracted to films that had a dreaminess to them.

DANIELS: Were you seduced by any actors or actresses.

WINTER: Clearly Diana Ross. Before, it was Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart in To Have and Have Not.

DANIELS: Attaboy!

WINTER: Bacall’s coolness and the way she was so starkly brilliant in the frame, the way she stood there and owned everything, I wanted to be like that, and I wanted to make films like that. And then when Purple Rain happened, Prince’s presence in my life went from zero to 60. He became a film idol to me. And there was also Diana Sands.

DANIELS: Oh my god, why don’t we ever talk about her anymore? She’s affected so many people. I mean, when you think of Diana Sands, didn’t she feel like an aunt?

WINTER: Completely. She was like a relative.

DANIELS: She had that rusty voice, like a smart Black woman of that time. And when she died, it hit us all. It was really painful.

WINTER: It was devastating. And I was also attracted to Rosalind Cash.

DANIELS: She’s the other one. Did they ever work together?

WINTER: They came up in the theater, so they may have crossed paths.

DANIELS: When you were coming into your own as a young artist, what was the experimental cinema scene like for you?

WINTER: I’ll tell you this. I grew up near the University of Chicago. So I had access to a real golden age of repertoire cinema companies showing weird movies all the time. I got to see Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures at a very impressionable age. It had people in crazy outfits rolling around naked on top of each other. Very gruesomely glorious, is what it was. I didn’t understand it. It scared the fuck out of me. And then I remember seeing John Cassavetes’s A Woman Under the Influence and I’d never seen anything like it. The intensity of the emotion, and the way it felt like it was just a story about a family, and we were eavesdropping on it. That blew me away.

DANIELS: Who are the actors and directors you came up with? Who do you consider your peers?

WINTER: When I came to the East Village in 1992, Todd Haynes was doing a lot of stuff. I became very good friends with James Lyons, who was Todd Haynes’s editor and cowriter for most of his early films. James taught me a lot, not only about life, but about film. He was very much an old-school New Yorker, a Times Square hustler type, but also an intellectual and a great editor and writer. He had AIDS and got very sick often, but always came back like a phoenix. He would be more handsome and wiser and funnier than ever. And there was Rose Troche, who did Go Fish. And my film, Chocolate Babies, debuted the same time as Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman did. So we did the cycle together, and we were always walking around going, “Well, we’re the only Black people here again.

DANIELS: Were friendships a big part of the making of the early work?

WINTER: Friendship was everything. Everything. The way that I understood how you make films is you bring your friends and your community together, you follow a dream, and you support each other and love each other and have as many laughs as possible

DANIELS: Is that still the case now?

WINTER: The friendships are harder to come by, perhaps. Now that I’ve been at this for 25 years or so, my friends from the ’90s are still my friends. A lot of those who stand with me now are the ones who have been with me throughout. And I mentor, so I do meet new people out in the world. I’ve become close with a lot of gay millennial comedy guys, like Jordan Firstman and Cole Escola. I met Jeremy O. Harris through this crowd, when he was still at Yale. I don’t think I have the same kind of cynicism as other people of my generation do. I’ve been through a lot, but I haven’t let it take away my spark. I’m still open to things. I look at myself and I’m like, “I feel like I look the same as I did when I was 25,” but I’ll see a picture of me at 25 and I’m like, “Oh, no, I do not look the same.” But my spirit feels the same.

DANIELS: How do you situate your films politically, in terms of queer Black cinema?

WINTER: As you well know, there was no Black gay cinema to speak of. And when we were foraging out in the ’90s, people would always make it clear: White guys are the directors, Black people are supporting actors. Black people do not belong in the director’s chair, the producer’s chair, or the DP’s chair.

DANIELS: How fucked up was that? No shade, no tea on Shirley Clarke, who made that movie you spoofed with Jason and Shirley.

WINTER: Yeah, the two most famous examples of Black gay subject matter were Paris Is Burning, which was not really Black and gay, but more of a trans-centered story, and Portrait of Jason, which had a Black gay person at the center but was a documentary by Shirley Clarke, and the position of the film and the position of the discussion around it was that this was good because a white person made it, and all the credit of the brilliance of the film was due to her. It wasn’t seen as a collaboration between Jason Holliday and Shirley Clarke.

DANIELS: There had to be Black gay filmmakers out there.

WINTER: There was Marlon Riggs. One of the reasons I kept going is that I got to do a master class with Marlon when I was in Chicago. He came to town, and we were hooked up and spent an afternoon together. He looked at my work and gave me encouragement, and I hung onto that to this day. Marlon Riggs said I was good and that I should keep going.

DANIELS: Did you ever meet the actor Raymond St. Jacques?

WINTER: No. Did you?

DANIELS: Are you kidding? I more than met him. He was ahead of his time and out and playing straight roles in the ’70s and ’80s and daring a motherfucker to come for him. He wanted to direct and he said the same thing to me that you said, that they could embrace him as an actor, but they would never embrace him as a director. It was institutionally impossible.

WINTER: It was institutionally inconceivable to the oligarchy that was in charge.

DANIELS: I think it’s the reason why I never bothered to even dream of directing at that age, because it just wasn’t possible. Then when we had to do it, it was independent.

WINTER: And it still is, for the most part. Spike Lee came out when I was a teenager.

DANIELS: He’s not gay!

WINTER: No, I mean, came out in the world. He showed a possibility that didn’t exist before. And the idiosyncratic nature of his aesthetic was really exciting.

DANIELS: I think Mario Van Peebles proved that he could do it his way. And certainly Melvin Van Peebles did prior to that.

WINTER: Yeah, there were lots of instances once you started looking. Hell, Mahogany was directed by Berry Gordy. There was always a way to seize hold of the apparatus. And I felt strongly that I could do it. When I wrote Chocolate Babies, I was connected with all these off-off-Broadway Black gay theater groups who were putting on shows like House of Lear, which was King Lear set in a ballroom. Most of my Chocolate Babies cast came from that production. I saw that show and I was like, “Oh my god, you guys are all amazing. Come be in my movie.” And they were.

DANIELS: How did Chocolate Babies even come to be?

WINTER: For one summer in Chicago before I came to New York I joined ACT UP. I had a great time, and we fought the power, but it was still a pretty racist organization. So, I took the floor after three months and read a speech condemning their racism, and then left. And as I left, all these people sort of followed me and said, “What do we do now? How do we deal with the race issues in ACT UP?” And I started to imagine, what if there was a group of Black, queer, drag-queen, trans people who were doing their own ACT UP? And at the same time, I was hanging out with some Black queens on the West Side of Chicago who had an important zine called Thing magazine. It was run by this guy named Robert Ford. And they took me under their wing as a little mascot. They knew Frankie Knuckles because they were all about house music.

DANIELS: Were you friends with Frankie?

WINTER: I was only an acolyte. I met him a couple of times, but I was too young to be friends. But I was in the room and I danced with him and I got that spirit. And then I mixed all that with the Bogart pictures that I loved, like To Have or Have Not. And so Chocolate Babies just came whole. I wrote it in two weeks, it made total sense. And I was like, “Oh, it’s a drama picture and it’s a comedy.”

DANIELS: You wrote it in two weeks, Stephen?

WINTER: Yes. On a typewriter. It was just one of those things. The spirit hits you and you’re the vessel. It was speaking through me. Most of the time when I’ve made art it’s because voices are speaking, and I listen and I write it down. A lot of lines in Chocolate Babies come from things that either I heard people say or came to me in that crazy two-week period where I was like, “Oh, I got it. I totally got it. And then this happens, and then that happens, and then they shoot him, and then they rescue him and all those things.” I love genre and genre tropes. So taking advantage of those and applying them to this kind of narrative came naturally.

DANIELS: Times have changed. How have you and your work changed?

WINTER: I feel like I’m both angrier and more optimistic all at the same work, I see an optimistic, angry person. And when I’ve looked in the mirror, especially in the last few years, I’ve seen a rageful person who is looking for hope. And that is how my work has changed, adjusted, evolved. I also think I’ve gotten better at it. I was pretty good before, but I’m really good at it now.

DANIELS: You have to feel good about the success of Jason and Shirley, right?

WINTER: I just got news from the Criterion Channel that they’re going to show Jason and Shirley and Chocolate Babies in September for six months. So that’s exciting. This is the beginning, darling. One of the things you’ve taught me is to always think big. You’ve always been like, “Think gigantic. Think fabulously big.”

DANIELS: How do you feel when you look at some of the filmmakers who were our age who were white. I mean, I know the answer, but were you angry? I used to be angry and bitter about it, and I turned it all into my work. Sometimes, when I look at scenes from some of my movies, I think, “That’s a bitter bitch right there who was holding so much animosity that young white men were just being given a platform.” Even young gay white men, who had far less talent than we had, were being given a platform.

WINTER: It’s not even the level of talent. You could be a hack and make a good movie, but so few of them had something real to say. There was no point to a lot of the productions. I’ve got a lot of good friends who are white and some who are gay and who have made some wonderful films, some of which I participated in. But it was the ease in which people can fail upwards or average upwards while I’m not even able to get to bat that was incredibly disheartening. I think it’s a testament to Black queer strength—and not just in film, but across the arts—that we were able to persevere. And not only hang onto our dignity, but hang on to our comradery and our sense of self. Because it’s a lot of years to put up with everybody saying, “No, you don’t fit the bill because of what you are.” It took a global pandemic and a national uprising to even get the conversation going that we’ve been trying to have for decades. But the other thing that I kept in mind—and this is a testament to my parents and how they maybe understand history—is that I would read biographies of Black artists, like Lena Horne or Abbey Lincoln or James Baldwin, and as successful as they were, they all had dreams that were deferred. They all lived in a world where it was institutionally inconceivable that James Baldwin’s screenplay of Malcolm X would ever be made by Norman Jewison or any other white guy. They would never let Abbey Lincoln be a true movie star. And then I think, those people are legends but what about all the others? Generation after generation of Black writers, producers, and directors who never got out of the dugout.

DANIELS: I get chills and anger when I think about it. Like Diana Sands or Rosalind Cash or Paula Kelly and those people who really inspired me to be better as a storyteller, and that the children today don’t even know who the fuck they are. That’s what makes my stomach turn. The Raymond St. Jacqueses of the world and what they represented are completely forgotten. But, their work will live on forever with people like me who are going to insist these kids know who they are.

WINTER: We’ve got to keep naming them, Lee. And like I tell my students, for the past 12 years there’s been an Oscar slot for intense, brilliant, important Black films that didn’t exist before. And the reason it exists now is because of Precious.

DANIELS: Oh honey, thank you. So, what are you working on now?

WINTER: I’m working on Sylvester with you, which is thrilling. I just want people to understand this is what it takes sometimes. In 1996, I made Chocolate Babies,and it got to the Berlin Film Festival. Then I got an award called the Rockefeller Fellowship in Film and Video. I used it to research the life of Sylvester, the disco star. I went to San Francisco and L.A. and met all the survivors, including his mother. I researched the fuck out of it. I wrote a screenplay, and then a mutual friend said, “I know who you need to meet to talk about this screenplay. It’s this guy named Lee Daniels.” And that’s how we met at lunch in Midtown. That was 1996.

DANIELS: It was love at first sight.

WINTER: Yes it was. I was like, “I feel like I’m looking at a mirror.”

DANIELS: Because I didn’t feel alone, Stephen. I wasn’t alone. As a queer, Black filmmaker, I was like, “Oh my god, we do exist.” We did.

WINTER: Yes, because I had such a mixed response to Chocolate Babies. Some people loved it, some people hated it. You loved it. And it was the thing that kept my life moving. But as we know, nobody was checking for Sylvester, nobody was looking out for Black gay material. The dream was deferred. And now, all these years later, we’ve come back to it, and this queen is going to live!

———

Stylist Assistant: Amanata Adams

Groomer: Rochelle Walker