XXX

Stephen Sayadian on Chicken Sex, Cuck Fantasies, and Café Flesh

Across a wild and varied career that encompasses orgasmic lobotomies, cumthirsty Jack-in-the-boxes, and interspecies rodent cunnilingus, Stephen Sayadian has cultivated a hyper-specific brand of nightmare boner, the kind that emerges unexpectedly at funerals or traffic accidents or at the peak of a fever-induced delirium. Having worked in the late 70s as the Creative Director of advertising for Hustler, the provocative hardcore magazine helmed by proto-edgelord and problematic stunt queen Larry Flynt, Sayadian was a deft practitioner of culture-jamming, creating satirical and highly-stylized ads for sex dolls and cigarettes that took the phrase “commodity fetishism” to its logical extremes.

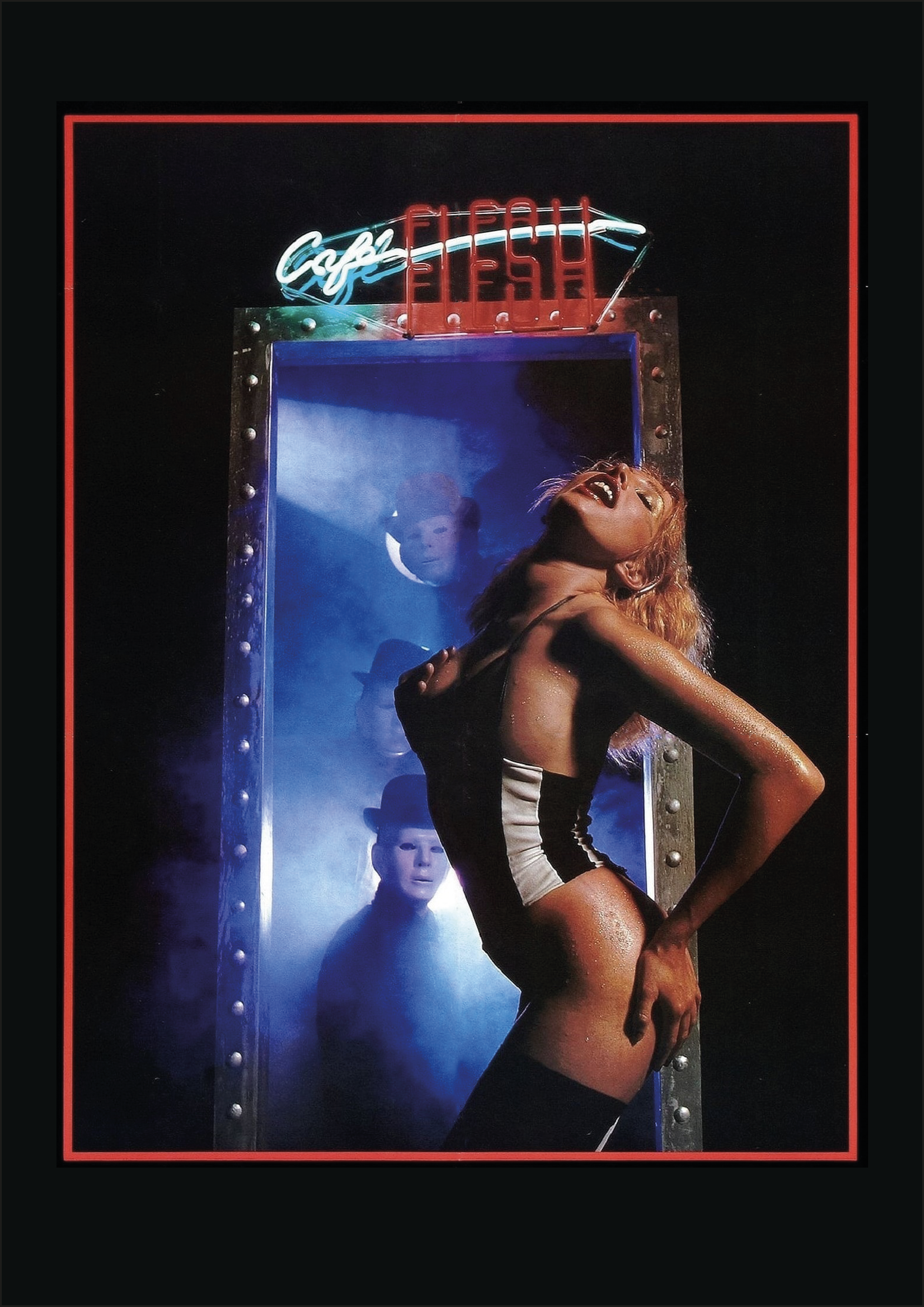

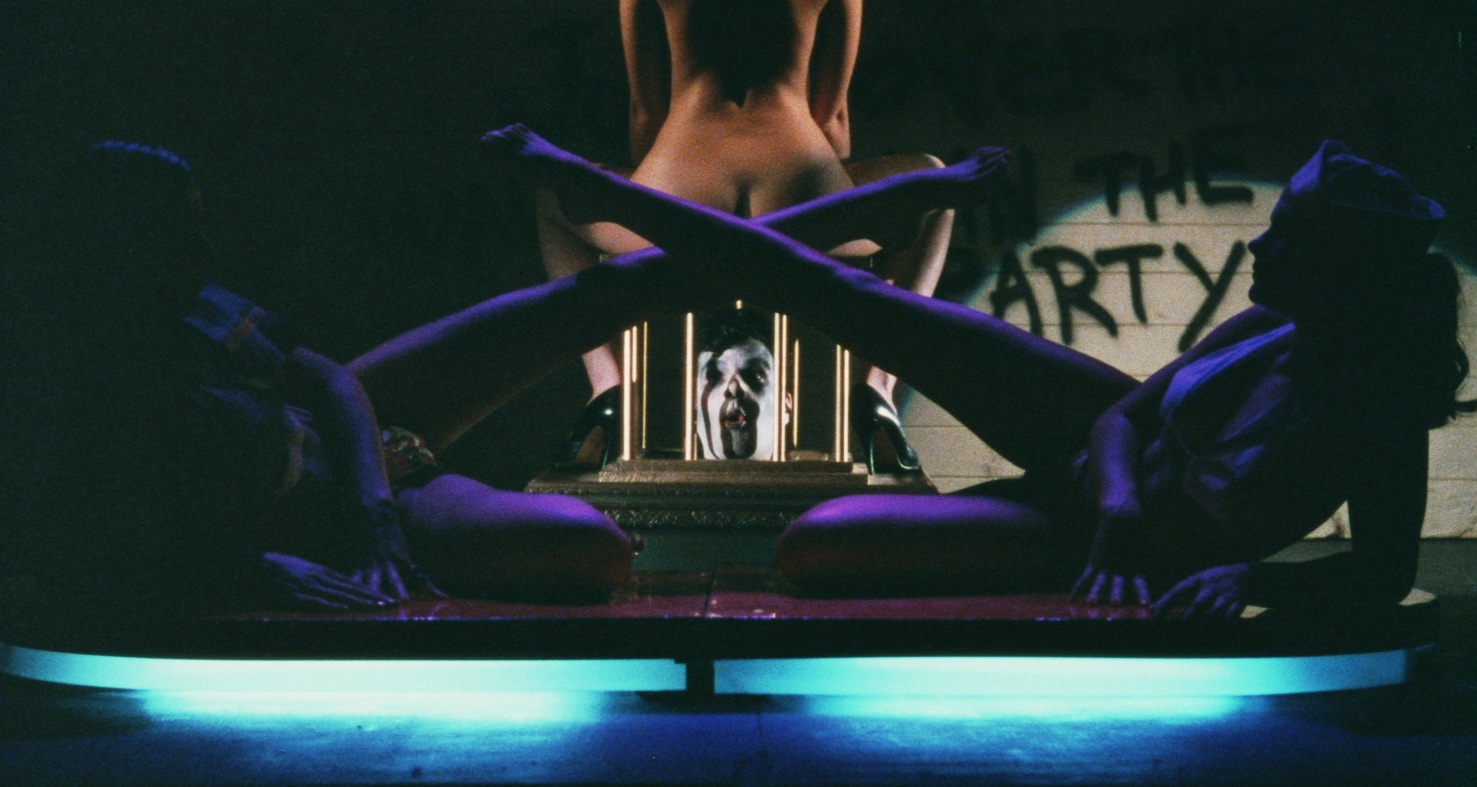

In the eighties, Sayadian became an avant-garde smut peddler under the alias Rinse Dream. His 1982 sci-fi art porn Café Flesh, which was screened in a new 4K restoration at Metrograph this past weekend, imagines a dismal future in which an unspecified radioactive event has rendered 99% of the population unable to fuck without experiencing unbearable agony. These “erotic casualties” gather in a smoky nuclear stronghold every evening (Weimar cabaret by way of Godard’s Alphaville) to watch the 1% “sex positives” engage in bizarre, government-mandated pornographic tableaus. With discordant lounge music and dialogue that reads like cut-ups from noir paperbacks and rejected Tampax slogans, Café Flesh repurposes skin flick archetypes (the horny delivery guy, the inexperienced Midwestern ingenue, the buxom elder nightclub proprietress with an affinity for taxidermied birds) to examine the detached and fragmented eros of the 1980’s media landscape. At 70 years old, Sayadian is candid and jaunty while we talk pseudonyms, stolen negatives, cuck fantasies, and sex with chickens.

———

KAMIKAZE JONES: Hi, Stephen, it’s Kamikaze. Nice to meet you.

STEPHEN SAYADIAN: Hey. I’m an instant fan of yours. I looked you up last night at about 3:00 a.m., which is the appropriate time to look you up. Very impressive. Really, why don’t you let me interview you?

JONES: That’s sweet. I’m sure we can go back and forth.

SAYADIAN: No, you’re really cut from the right cloth, in my book.

JONES: I’m glad to hear that. I was thinking a lot about aliases and pseudonyms because obviously, I go by my “porn name,” which is that childhood game you play when you take the name of your first pet and the name of the first street you lived on. I had a hermit crab named Kamikaze, and I lived on Jones Street.

SAYADIAN: It’s a really great pseudonym. My pseudonym is Rinse Dream, and there’s a synth band called Rinse Dream. I get emails from various people asking if they can use that name for any number of projects. You can go a long way with a pseudonym.

JONES: Your pseudonym sounds like it came from some sort of beauty salon ad copy, which is very apt.

SAYADIAN: Jerry Stahl, who’s been my writing partner since ’76, is the name king. I wanted to use my real name on my adult films. But when I was doing it, you could get thrown in jail. They’d find who was making the film and arrest you for paying people to have sex, so you would have a prostitution rap. That’s why I had to use a pseudonym, and everybody else involved with the film, for the most part.

JONES: It becomes such an interesting part of porn history, self-mythologizing through the alias. How has working with the Kinsey Institute been for the 4K restoration of Café Flesh?

SAYADIAN: Kinsey is great. This restoration was probably the most difficult task I ever engaged in because my negative was gone. The negative was stolen decades and decades ago, along with a pristine print I had. My storage locker had all of my archival still work of 25 years and all of my movie one sheet work, and it got stolen along with everything else in the storage. I put up an ad, but it never came back. The restoration producer, who is an amazing film scholar and historian and who really is responsible for the revival of my old movies, said, “We’re going to have to go on a world search to find prints if we can’t find the negative.” After a year, we realized there were only two existing prints in the world. He went everywhere: Europe, Australia, Japan, South America. The two people that had prints were the UCLA Film Archives—I think it was their only hardcore film—and Kinsey. We combined the two prints to do the scan, and it took almost two years to actually finish what is playing Friday night at Metrograph.

JONES: Wow. Is there anything that pops out for you in revisiting the film in our current moment?

SAYADIAN: Yes. To this day, the best thing about the entire film is the look, the photography. For a little film that I shot in 10 days for about $90,000, it looks pretty remarkable. And I think viewers will get to see that. When it was originally released, it got covered in all the major press, and even people who had total disdain for the whole thing could not deny how good it looked for a film of that budget. And people who’ve had to watch illegal DVDs or cassettes of the film before will be surprised. It never had a Blu-ray release, in fact It barely had a proper DVD release.

JONES: In New York at the time, the No Wave Cinema movement was happening. I remember reading that Darby Crash of the Germs was your assistant.

SAYADIAN: He wasn’t my assistant, but he used to hang around. My studio was just across the street from the first L.A. punk club, and the best one, called The Masque. It’s where all the bands that came out of L.A. in the late ’70s and early ’80s—Wall of Voodoo, X, Bangles, The Go-Go’s, they all came out of The Masque. Darby had the Germs, and the bands never had any money. I had this working studio, I was doing a lot of movie one-sheets. All the rockers would come through and say, “Hey, Stephen, what do you need? Can we paint a set? Can I make you coffee?” I got to know everybody on the scene very well.

JONES: And you and your collaborators all met working at Hustler, where you were the Creative Director of humor and advertising. I remember you saying that you were recycling a lot of the sets that you used for movie one-sheets, and that’s why you could afford to get away with what you did on the budget that you had. Were the tableaus, especially the pornographic tableaus in Café Flesh, informed by your work in editorial or advertising?

SAYADIAN: Very much so. In fact, on Saturday night, I’m going to show the whole genesis of how the work I was doing at Hustler was subverting the men’s magazine business, especially with the ads. When I first got to Hustler back in ’75 or ’76, they were still accepting national advertising. There were cigarette and stereo ads and all the things you would find in men’s magazines back then. They would tell us, “We’re not going to buy the back cover if you keep going in this wild direction.” Not just the sexual explicitness, but we were starting to introduce politics and we were all a bunch of left-wingers, and Larry [Flynt] was the most [left-wing]. There was a great Esquire cover of Hugh Hefner, and he was looking at a Playboy. But inside the Playboy you could see he was actually reading Hustler. And the headline is, “What Have They Done to My Girl Next Door?” We would start making fun of Penthouse and Playboy for just how square they really were, which was the real appeal of the magazine to me. Larry was getting this pressure and he said, “Fuck it. I’m not going to even have advertising. Mad Magazine doesn’t have advertising. I’m going to create my own ads. I’ll start manufacturing sex products.” He offered me a job as an editor, and I’m just a kid, I’m like 22. But he had seen my parody work and said, “Do you think you could create all these ads for this company of ours?” He said, “I don’t care if we don’t sell anything, I just want it to be entertaining and something the readers will enjoy. If they buy the product, that’s fantastic. But if they don’t buy the product, at least I want it to be entertaining.” The next thing we knew, we had this big warehouse full of staff making dildos and love dolls and cigarette rolling papers for pot, all sorts of crazy products. I started doing these ads and it turns out they were not only well-received, but they sold the products. At one point, we were making nearly as much money from the ads as we were from the magazine itself. It was like the perfect job for me because I had to be a creative machine back then.

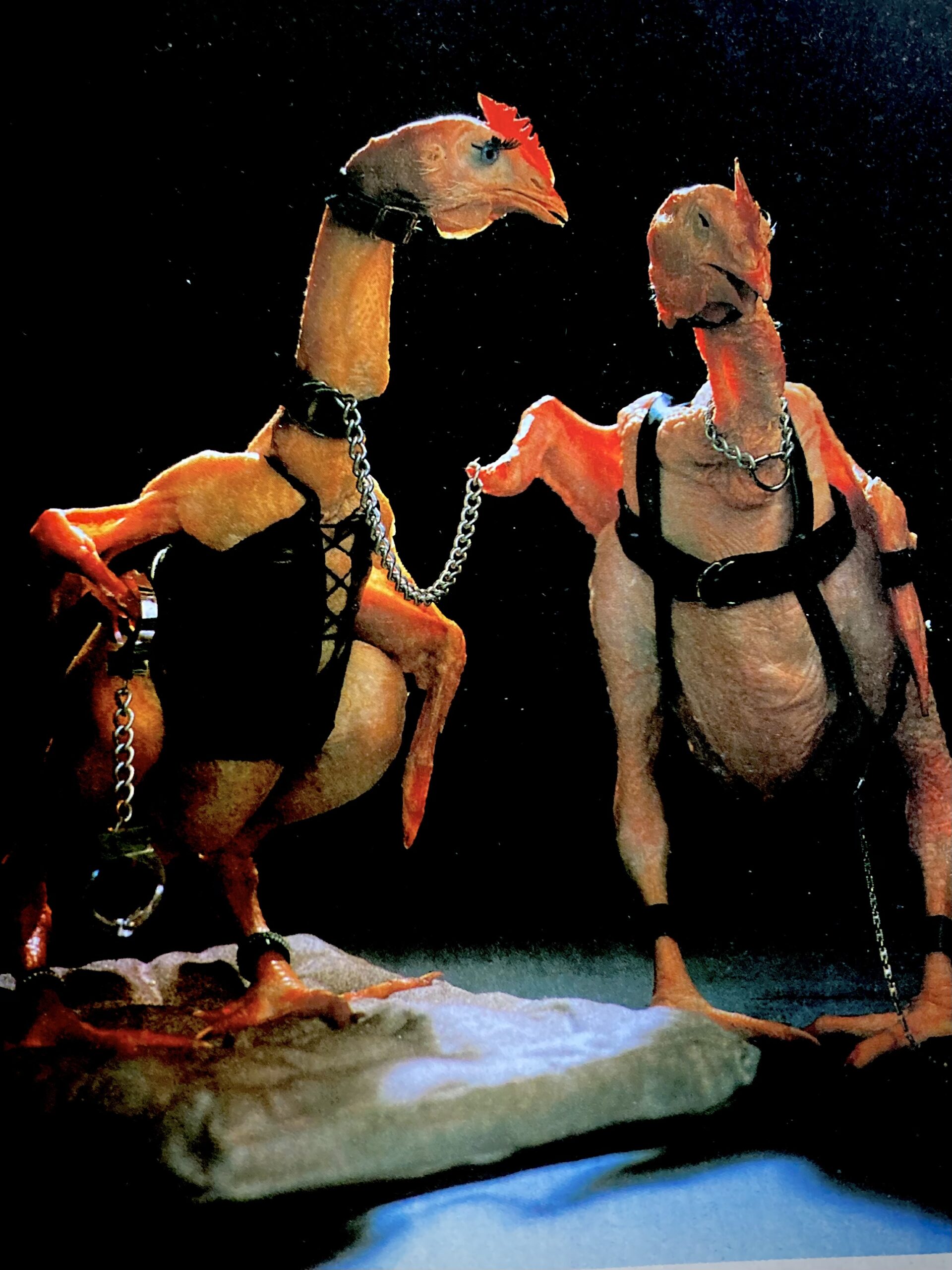

JONES: I feel like in Café Flesh and your ad work, there’s a critique of the nuclear family as represented in corporate culture. I was looking through your ads, especially the tableaus that involve poultry, and I was wondering if that had anything to do with the rumor that Larry Flynt allegedly lost his virginity to a chicken as a child?

SAYADIAN: I cannot believe you know that story. Yeah, because Larry was raised on a farm. He insisted that was true. I don’t think it was. He always had a twinkle in his eye. When I went to work for him, he was 33, just a wild man. He was really a terrific boss, and I was the only employee he gave total creative freedom to. A few months before he died, I was visiting him at the office, and I said, “Larry, why did you give me all this creative freedom?” Because he ruined me once I started taking other jobs and I had all these rules. To this day, I can’t take any interference in anything I do. He spoiled me at such a young age. But the chickens didn’t have anything to do with that. I went to a poultry shop and they had live chickens, and when I saw them without feathers, I just thought, “Wow, they would look fantastic in photographs.” I did my first one way back in ’76. Some people have asked me, “Were you influenced by Eraserhead?” Because there’s that scene with chickens dancing or something. I said, “I was doing those chickens before David Lynch.” And I didn’t stop doing them. I did an entire series from ‘75 to ’85. And they eventually found their way into a beautiful French magazine called Zoom. When I was 16 years old, one of my goals was to be published in this magazine. Zoom was like the New Yorker of photography magazines.

JONES: Thematically, Cafe Flesh seems to really be prescient in a lot of ways because it was released right around the time of the AIDS epidemic and dealt with the aesthetics of fascism and addiction in really interesting ways.

SAYADIAN: All intentional, and all true, Kamikaze. Very astute. The first tableau is a milkman and a 1950s housewife having sex. That’s the old cliche, the pizza delivery guy or the milkman. The women were always the typical homemaker, Donna Reed or Samantha Stevens, some ’50s or ’60s mom. And the scene with the pencil head in the office, that was the boss and the secretary. The third one was about nuclear issues under Reagan. And of course, AIDS. Before the word AIDS was in the vernacular. I was reading the Village Voice and they talked about the gay plague. And I was like, “What is the gay plague?” I had done some research, which was very hard to find in 1980, and at that time they thought it was something at the bath houses that was causing this. I told Jerry, “This would be an amazing plot for an adult film.” Although the big disappointment, of course, is that you look at Café Flesh like, “Why aren’t there two guys?” The porn industry was so conservative.

JONES: You couldn’t get funding if you were doing a hardcore scene between two guys?

SAYADIAN: Never in a heterosexual film. There were the Joe Gage movies, and Kansas City Trucking Company. There were gay-gays. I had an opportunity to do a gay film, but it never worked out. I wrote the script. I was going to do one very much in the fashion of Café Flesh. I was getting the financing because back then I used to get just script-writing assignments. I would write two scripts a day, and they were paying me like $1,500 a script, so I was getting $3,000 a day and writing two porn scripts that were like 40 pages. The point is, you could make a really good living back then doing that. Of course, the minute video came, that was the end.

JONES: That feels like it comes from a longer tradition, too, of Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin writing smut for anonymous benefactors.

SAYADIAN: Of course. When I first started writing smut, I wrote some paperbacks and they used to pay it by the weight instead of by word. They’d weigh the pages.

JONES: I think it’s funny how, in that context, you could also read Café Flesh as a feature-length castration anxiety or cuckolding fantasy.

SAYADIAN: Well, how about the original ending we wrote, which they wouldn’t let me use? At the end of the film, the main character, Nick, goes up to the stage while his wife’s having sex and he chops off his penis and hands it to her. And they said, “Stephen, absolutely not. Under no circumstances. You’re going to waste money because you’ll never be allowed to use it.” Who knew about director’s cut back then, especially in a porn film? I said, “I’ll do something else.” So I had Nick climb up to the rafters and hang himself in the last shot. He was swinging while she continued to have sex, which I thought was a really good image.

JONES: Yeah, it would’ve been beautiful.

SAYADIAN: I know. But they wouldn’t let me do it.

JONES: But the ending is hypnotic because he gets pulled away by this mutated—

SAYADIAN: Yeah, it’s abrupt. But I love doing an intro to the film because I always give a background and I reframe how anybody watching this film should see it. For Café Flesh, it really does help to know a little bit of the backstory, and why the sex is so boring and mechanical. I always wanted the sex scenes mechanical and not sexy at all because I thought it worked with the theme of the movie. But I look at it now and I think it was a mistake. I think I could have done both, but how do you have a sexy theme with somebody wearing a pencil on their head and in a rat-faced mask?

JONES: Even if it wasn’t intended to be sexy, and it was intended to be the opposite of erotic, it’s kind of generative in producing new eroticisms for posterity.

SAYADIAN: Yes, I was the only voice in the restoration process that said, “I wish we could change it.” The producer of the restoration, and somebody I respect and would not have had a second career without, said, “Stephen, don’t change a thing.” So I let him have the final say.

JONES: Speaking of revision and unrealized projects, I wanted to ask you about the shoot that you did for Frank Zappa for his unrealized musical Thing-Fish, and also about a script that you had written with Jerry, I think, called “Hormone Alley.”

SAYADIAN: Hell yeah, that was our transgender script. We were so ahead with that scene. That’s why I have such a great queer following. But with Thing-Fish, the Zappa musical, Frank called me out of the blue and said, “I like what you do.” What Frank didn’t know, even though we became dear friends, was that I was a Zappa fanatic in high school. I bought his Freak Out! album in 1967 when I was 13 or 14 and fell in love with everything he did. My room at my parents’ house was like a shrine to Zappa and a few other people, including Mitzi Gaynor. But anyway, I finally told him, “I think what you responded to when you saw my work and liked it was not so much the work itself but the sensibility, which I stole much of from you, just subverting everything you can in an entertaining way.”

JONES: Is there anyone working in contemporary cinema that resonates with you?

SAYADIAN: I haven’t found too much that I love. Someone told me Peter Strickland does interesting things. Do you know him?

JONES: I do. I love Berberian Sound Studio. The Duke of Burgundy is great. I think you would actually get a kick out of it.

SAYADIAN: Yeah. Someone told me that I would like him. I’m a film fanatic, especially silent films, going all the way to the Golden Age of Hollywood and, of course, the underground. When Café Flesh originally came out, it played at midnight the Nuart and broke the house record. When Dr. Caligari, my next film came out, the critics for the Los Angeles Times gave it an over-the-top review and I started getting calls from the studios. They didn’t even see the movie, but read the review. That was Los Angeles, right? It doesn’t matter what the film is, as long as people are talking about it. I got an offer to pitch a Texas Chainsaw Massacre sequel. I wanted the job, but unfortunately I made a fatal error. I envisioned the film as a DayGlo ballet, much like Dr. Caligari, very psychedelic, only with chainsaws. I told the producers, “Imagine Leatherface in a tutu.” By the time I was done, they were spraying the room with Glade. They did not get it.

JONES: Well, it sounds like something that could still manifest in the future. I’m going to call it here, but it was really a pleasure to get to talk to you about this work.

STEPHEN SAYADIAN: I want to hear more about what you’re doing, hauntology. I don’t even know exactly what that is.

KAMIKAZE JONES: We can definitely talk. I’ll come to Chicago.