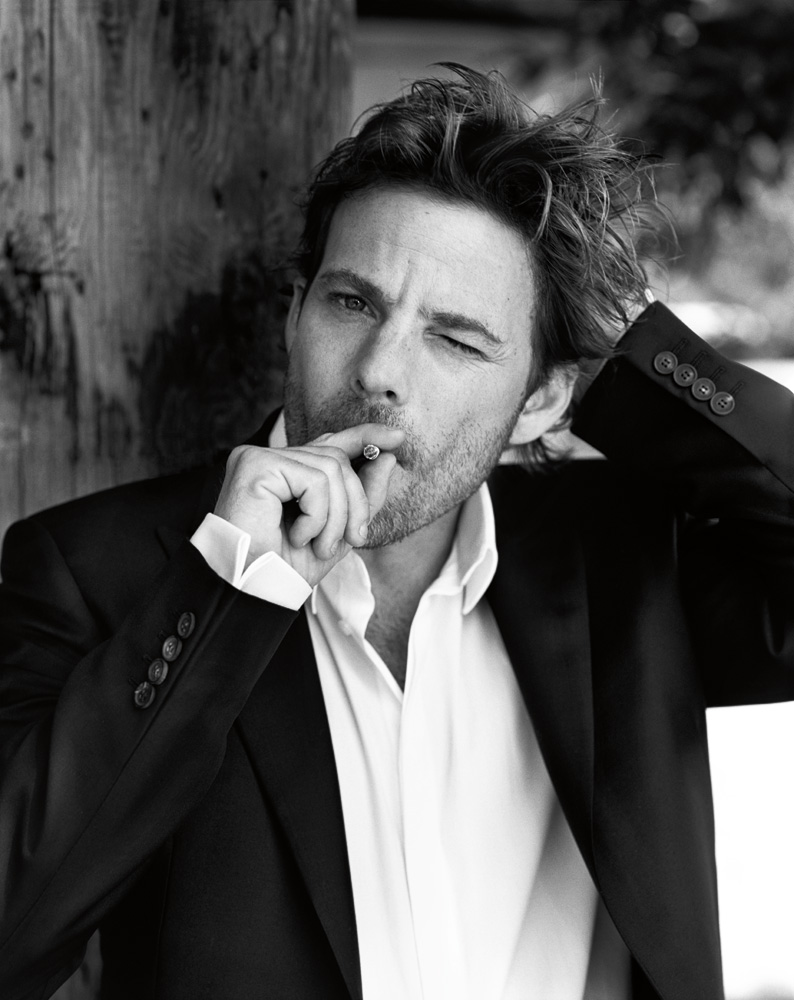

Stephen Dorff

Sofia Coppola’s casting choices are always as insightful as they are adept. So it was something of a surprise—and then, on second thought, it wasn’t—when the director picked actor Stephen Dorff to star in her fourth feature, tentatively titled Somewhere and set at L.A.’s Chateau Marmont hotel. Dorff, now 36, is not the first actor who comes to mind as an off-the-wall leading man although he certainly looks like one and has been acting for more than two decades. To his credit, Dorff has taken on roles that few men in the industry could—or would—dare to tackle: He played luckless fifth-Beatle Stuart Sutcliffe in the 1994 band bio Backbeat, iconic transsexual Candy Darling in Mary Harron’s I Shot Andy Warhol (1996), and kidnapping psycho director in John Waters’s 2000 comedy Cecil B. Demented. Dorff’s career has never really followed a straight line, but lately it seems as if he’s finally getting the recognition he’s deserved for all of his brilliantly scattershot filmography. This summer he took a turn as John Dillinger’s conspirator, Homer van Meter, in Michael Mann’s Public Enemies, and aside from the Coppola project, in which he plays a massive Hollywood star dealing with both his 11-year-old daughter (played by Elle Fanning) and his own emotional implosions, he also appeared in and co-produced the biting prison drama Felon (2008), and is now working on an Adam Sandler film, Born to Be a Star, in which he plays a porn star. All of this eclecticism sounds about right for a versatile performer like Dorff. Here he talks to his close friend Owen Wilson about what he’s gained and what he’s lost and what he’s still committed to learning (Guitar Hero).

OWEN WILSON: Just relax, buddy, I’m a veteran—I interviewed Tony Shafrazi. The best interview they ever had in Interview.

STEPHEN DORFF: [laughs] Do we chitchat or do we go right into it?

WILSON: Let’s go right into it. You just finished a movie that Adam Sandler’s company is producing, Born to Be a Star, in which you play a porn star. It’s a comedy. You haven’t done a lot of comedies, have you?

DORFF: No, I mean I did a movie with John Waters called Cecil B. Demented, but I haven’t done a comedy like the kind you do—a straight-up comedy. It was an exciting opportunity, and I got you to help and coach me on it, buddy!

WILSON: Talk about your Born to Be a Star character—it’s kind of a funny character.

DORFF: His name is Dick Shadow. At the beginning of the film, he’s at the top of his game. Then there’s Bucky, played by Nick Swardson, who realizes his parents were porn stars and is destined to come to Hollywood. Adam wrote the script with Nick Swardson and Allen Covert.

WILSON: It’s a nice way of making movies—to do it with your friends where you can keep control over it.

DORFF: Yeah, it was a really loose and fun atmosphere. Because Sandler has made so many successful films, he’s really laid out a friendly family atmosphere. You see a lot of familiar faces you’ve seen in many of his other films, and I just had a great time. So I might be giving you a little competition in the comedy area.WILSON: [laughs] You’ve been acting since you were a kid, right?

DORFF: Yeah. I mean, well, I did my first film when I was like, 12 or 13. Then, besides a few commercials here and there, I didn’t really act again until I was about 16.

WILSON: What was your big break?

DORFF: Probably The Power of One [1992], this film I did in Africa with Morgan Freeman and Sir John Gielgud. I found myself working with some amazing actors, and I thought I was just going to go to college. I had auditioned for a couple of theater schools, like Juilliard.

WILSON: Did you get in?

DORFF: I got in, yeah. I remember getting that movie at the same time and asking my parents what they thought I should do. It was obvious that I didn’t really feel ready to jump right in with actors on that level, but I was so flattered I accepted. It just seemed I was destined on that road as a youngster—to be around adults who I could learn from.

WILSON: Did you have anyone who was a mentor? I remember my dad always saying that when he started his own business, he was surprised where the help came from. It seems like there is always a person who helps out along the way.

DORFF: My first manager was this lady named Booh Schut. She actually worked with me on my auditions. It was pretty surreal to be auditioning as a kid, and I’d get close to these actors that I really respected. I remember River Phoenix in particular. I met him at an audition hall or something.

WILSON: For Stand By Me?

DORFF: Well, I had auditioned for Stand By Me [1986] when I was like 8.

WILSON: You did?

DORFF: Yeah. [laughs] I was really young, and I got a callback but . . .

WILSON: Which character did you audition for? Because you were kind of a roly-poly, heavyset little kid.

DORFF: [laughs] Oh, I don’t even remember what part. Maybe the Corey Feldman part?

WILSON: You have an affinity for accents. I remember first seeing you doing British in Backbeat. And you did South African in Power of One, right?

DORFF: Yeah, that was what was weird. At first the best roles I was getting were ones playing English people. First I was doing English–South African, and then I used the same dialect coach to do Backbeat, which was a Liverpudlian accent. That one was hard. I remember I once had a meeting with Sydney Pollack and the playwright Tom Stoppard, and they thought I was English. I said, “I’m just from the Valley!” [laughs] Just from the San Fernando Valley! It’s weird because I found out later that English actors like Ewan McGregor and Jude Law auditioned for some of those roles. Then, when the whole crop of British actors kind of rose up, I never played English again. Saved a lot of money on dialect coaches!

WILSON: It’s a cliché to call you a child actor because you did only one movie as a kid. Your father has a pretty interesting background in music, right?

DORFF: Yeah, well, I moved to L.A. when I was like, 6 months old. I was born in Georgia ’cause my dad was going to college at the University of Georgia for music. Then we moved to the Valley, and my dad was a songwriter out here. After struggling for a little while, he had some pretty big hits. He wrote that song “Every Which Way But Loose” for the Clint Eastwood movie.

WILSON: That’s the one with the monkey in it.

DORFF: Yeah. I have all these really cool pictures of me as a kid on Clint Eastwood’s lap or sitting with Ray Charles. I have one where I’m with Johnny Cash in the studio. So it was kind of a cool childhood because my dad was in the business, but not really in the business . . .

Sometimes the bad guys are the juicier roles. But I definitely wanted to play a gangster. I think the gangsters have more fun, you know?Stephen Dorff

WILSON: Did your parents encourage you with acting? Or was it a symptom of being in Los Angeles and saying, “Oh, I’d like to be an actor”?

DORFF: Well, no. I was on the set with my dad, and I remember seeing kids on set and thinking that was so cool and wondering where they went to school and finding out they have tutors, like, Wow, they have their own teacher? [laughs] And you only have to go to school for three hours a day? This is awesome! You know? That was kind of the first thing that got me excited about the gig. Plus I went to a lot of schools in L.A. that were private schools, but I just never really had a great teacher, so I found myself bouncing around a lot. I never created a real rhythm with other kids. Acting was something that my mom thought gave me self-esteem and confidence. If I tried and did well at school, they would take me to audition—that kind of thing. I didn’t have stage parents. Every kid needs their thing, and that was mine. When I got older, I started watching movies and learning and thinking, I want to work with Jack Nicholson!

WILSON: Was he your favorite?

DORFF: Yeah. I just loved watching him, you know? Even as I got older I would study his earlier movies like from the ’70s. Even in later movies, like The Witches of Eastwick [1987], he was so great. I really made a conscious decision after The Power of One, that I wasn’t really in it for the money. I wanted to build up a good filmography. I wanted to get a chance to work with the best, and that would help me and make me better. So I was always conscious about like, who’s in the movie? I would almost ask that even before reading the script: “Is Jack in it?”

WILSON: Did you get nervous working with Jack? What did you learn from him?

DORFF: So many things. Just control, and ease, and how to get to the place where you’re relaxed in what you’re doing, no matter what it is. I was definitely nervous. But it was so exciting to be on that set. I remember sitting there with Nicholson on one side, and Michael Caine on the other, and being the kid there. It was like, Wow, man, this is what I want to be doing.

WILSON: You guys filmed in Miami?

DORFF: Yeah. [laughs] Going out with Jack at night, and then him not having to go to work at 7 a.m. but me having to, and trying to hang with my favorite thespian and make the 7:30 call. But I made it through!

WILSON: Seems like you’ve always been able to maintain that excitement for acting without burning out on it. And lately you’ve been producing and doing some music stuff. You produced that movie Felon.

DORFF: Yeah, I produced that with my friend Tucker Tooley.

WILSON: In Felon you play a wrongly convicted guy who gets kind of railroaded by the system. There are some pretty intense scenes, especially between you and Val Kilmer.

DORFF: It was a great script, and Ric Waugh—the writer-director first-timer—researched the hell out of that movie. So by the time I got there, all the details were really there. It just felt like we were making something real as opposed to a Hollywood-type prison film where you recognize the people playing the guards, you recognize the inmates from episodes of Prison Break or whatever. We were going to do something that was really based on what happened in Corcoran State Prison. I had a character to really sink my teeth into. And it wasn’t a villain or the normal role you expect me to take. That’s nice because we’re getting older, buddy!

WILSON: And now you get to work with Sofia -Coppola, which is exciting because she’s only done a few movies, and each one is very special. How did that come about? Because you play the lead.

DORFF: I really think it’s probably the best part I’ve ever been given. I’ve known Sofia for a long time, since I was growing up, and we’ve been friends from kind of a distance. I was blown away when all that excitement happened over her for Lost in Translation. It reminded me of being friends with you when you got nominated for [the Oscar for best screenplay for] The Royal Tenenbaums [2001]. It’s exciting when it happens to one of your peers, someone you care about. Over the years I had worked with her dad [Francis Ford Coppola], workshopping some of the things he was directing. I’m really lucky to have the opportunity to work with Sofia. Somewhere takes place in the Chateau Marmont—I’m going to be moving in there soon. I’ll actually be living there as we shoot, which is kind of cool. My character is going through some kind of personal crisis.

WILSON: He’s a movie star?

DORFF: He’s an actor, yeah, who’s got a kid. And there have been a lot of changes in his life. It’s really in Sofia’s style. It’s very poetic and sweet and unique. It’s not the kind of scripts we get sent very often.

WILSON: It really doesn’t even have a thorough script, does it?

DORFF: Her scripts are famously short. She doesn’t write everything down and spell it out for the reader; I think she leaves a lot in private.WILSON: It’s better. I always think it’s hard to read scripts because, first of all, a lot of the time they’re just boring. It’s hard to read a script from start to finish, like a book, and enjoy it just for itself. The script is supposed to be the blueprint for the movie. So you can read a script and be like, Okay, but then it can turn into a good movie. I feel like I’ve only read a couple scripts ever where I thought, Wow. I remember being in Dallas, and one of the guys who helped us with Bottle Rocket [1996] knew Quentin Tarantino when Reservoir Dogs [1992] was happening. He had a copy of True Romance [1993], and I remember he gave that to me and Wes. That script seemed so great, just so exciting and different from everything. It’s nice to read something that has its own voice, and Sofia’s script obviously does.

DORFF: Yeah, It’s an exciting time. I’m getting some great opportunities. I’m growing up. I think that’s the goal to try to keep finding those new things and take those risks,

WILSON: And you just did Public Enemies with Michael Mann.

DORFF: Yeah, Michael Mann has always been one of my favorites. I loved The Insider [1999], I love The Last of the Mohicans [1992], I love Heat [1995]. Public Enemies was the biggest film I’ve ever worked on. I was on set for 70 or 80 days for that movie. It was great to work with Johnny [Depp]. He’s always been an actor I’ve looked up to and respected.

WILSON: When you and I first met, I remember you were living in that house at the top of Mulholland that he had lived in previously.

DORFF: Yeah it was a weird connection. He had rented the house years before.

WILSON: It’s a great house.

DORFF: It was just a cool tree house on top of a mountain with a killer view. But on set he was very generous with the actors. It was an intense shoot. We had a lot of nights. I play Homer Van Meter, one of Dillinger’s crew—kind of the dangerous one—they were together almost all the way up until Dillinger’s death.

WILSON: You play a hothead.

DORFF: His job is basically to control the front of the bank while they’re inside taking care of business. So Homer was documented as having done a lot more of the murders.

WILSON: That’s one of your specialties, playing a hothead. [both laugh]

DORFF: Sometimes the bad guys are the juicier roles. But I definitely wanted to play a gangster. I think the gangsters have more fun, you know?

WILSON: Yeah.

DORFF: We’re being chased by Christian Bale and his team of authorities, but the gangsters had a lot of fun back in 1934. Dillinger busts me out of prison in the opening, and from then on, it’s basically the last year of Dillinger’s life. We go on the tear-up until things start getting ugly.

WILSON: You know, this interview wouldn’t be complete without a mention of . . .

DORFF: Shafrazi?

WILSON: Shafrazi and American—

DORFF: American Greats. [both laugh]

WILSON: My dad always loves seeing you because you always bring up the book he did, and he always gets real excited.

DORFF: I was at the book signing for American Greats. I believe it was at Neiman Marcus or somewhere in Beverly Hills, and I’ve still got that book on my bookshelf, Robert A. Wilson: American Greats. And your interview in the issue of Interview with Tony Shafrazi is great! He was great in Life Aquatic with you. He keeps always telling me, “Get me in some of these movies,” and so I had a part for him at the porno party and he wanted to reschedule—he doesn’t realize when you schedule a certain scene, you have to be in town to shoot it. They’re not going to rearrange a whole film for your travel itinerary, you know?

WILSON: Yeah.DORFF: Now I’ve warned him again. I said, “Sofia would love you to be in this film and do a little appearance, maybe a little scene with me in the hotel. But you have to be available at the end of June.” And he, you know, he’s gotta pay his dues before they’re gonna start arranging whole films around his schedule.

WILSON: Right. [laughs] That’s what it was like on Zoolander [2001]. He was in it for a second just to show a little bit of New York nightlife. I remember him afterward saying, “Please talk to Ben.” He felt his character needed more of an arc, to come back at the end and say that the nightlife isn’t so great. [both laugh]

DORFF: I mean, Tony taught me all about art. He got me buying art when I was young, and I still have some of those things. Tony really opened up my eyes to a lot of things.

WILSON: What music have you been listening to?

DORFF: A lot of stuff. My little brother Andrew is a songwriter in Nashville. He just had a hit with this country singer Martina McBride.

WILSON: Creative family, you guys . . .

DORFF: Yeah, it’s been an intense year for my family. I lost my mom last year, but I feel like she’s really been with me and with us, guiding us. I’d never really lost anybody before in my immediate family. Your mom is the person you don’t ever want to lose, but in losing her, I had all these great things that started happening. I think she was part of me getting the whole Sofia movie,

WILSON: You took a year off to be with your mother when she was sick, too.

DORFF: Yeah I found it hard to keep going away, doing a movie, coming back . . . When Michael Mann came to me for that movie right after everything, I thought for a while that I couldn’t do it. But in the end, I think it was the best thing for me. I really thank him for bearing with me and being an incredibly supportive director at a really rough time. He gave me a great opportunity, a great role, and that really saved me. If I hadn’t done a film for those six or seven months, I probably would have been chewing myself.

WILSON: Your mom had this great spirit.

DORFF: Yeah, my mom was the kind of woman who, if I was the worst actor in the world in my first performance and literally the whole audience walked out of the theater, she would have been saying what a great performance I gave. She was kind of the ultimate mom, I mean, almost too nice sometimes. She was just a really special lady, and I was really lucky to have the relationship that I had with her. It kills me that she’s gone, but at the same time, I think she’s given me strength. I always remember she would want me to do the right thing and make her proud, so I think that’s what I have to focus all my energy on, to be a better person and do great work. I think my mom will be up there, hopefully smiling.

WILSON: In Sofia’s movie, you’re going to play a father in a kind of Paper Moon [1973], Ryan O’Neal/Tatum O’Neal relationship. How old is your character’s daughter?

DORFF: She’s 11.

WILSON: Did you draw on your sisters for inspiration?

DORFF: Yeah, I have two great half sisters. I never had a sister growing up, and now they’re 9 and 12. I have a really cool dynamic with these girls. They’re like people now. They’re so smart. They love to come to the beach and surf. What I’ve realized is that kids are busier than us at our busiest time, because they have like 900 hobbies; they can never hang out. I wanted to get my sister to teach me Guitar Hero, but I can’t even get an appointment with her because she’s got gymnastics, or swimming lessons, or French lessons, or track and field, or ice skating, or Cub Scouts—it’s impossible. I think the same goes for all young kids. I know the actress who will be playing my daughter, Elle Fanning, has got a serious schedule on her. It’s like, I’d be tired.

WILSON: Well, jeez, buddy, I’ll teach you how to play Guitar Hero. I feel bad.

DORFF: I taught myself . . . It’s hard, man. It has nothing to do with playing guitar. It’s putting the right fingers on the right colors. I have to get good at it because I’m playing it in Sofia’s movie. So I have to practice all the time.

Owen Wilson is an actor and an Academy Award–nominated screenwriter.