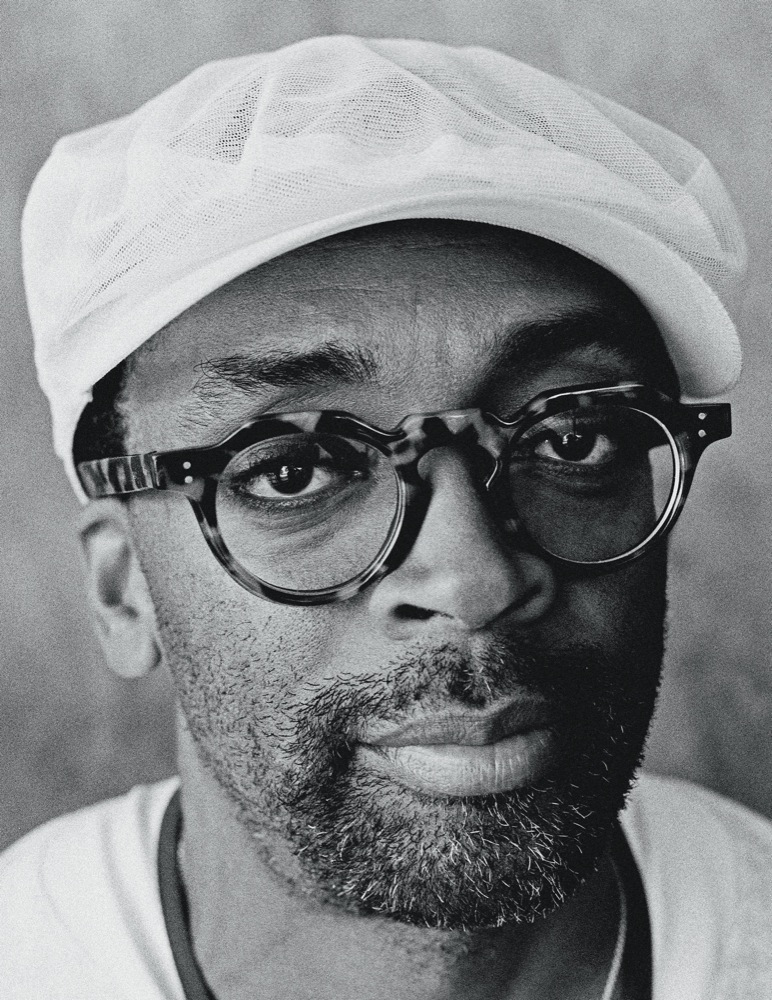

The American Dream, a Spike Lee Joint

For more than 30 years, the American Dream has been refracted through the prism of a Spike Lee Joint. Be it Nola Darling turning bed-hopping into a feminist power trip in She’s Gotta Have It (1986), a pizza parlor in Brooklyn’s Bed-Stuy neighborhood transforming into a Rorschach inkblot of ’80s race relations in Do the Right Thing (1989), or a Harlem gangster who becomes a U.S. martyr in Malcolm X (1992), Lee’s explosive portraits of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness have always explored the difficult underbelly of America. From Last Hustle in Brooklyn (the very first film he made, which debuted 31 years ago, when he was a student at Morehouse College) to his latest epic, Miracle at St. Anna, Lee’s output is nothing short of profound. And he’s only 51.

Miracle at St. Anna is based on the celebrated historical novel by author and composer James McBride, who also penned the script. The film depicts the World War II–era story of the U.S. Army’s 92nd Division—a unit of African-American soldiers who fought in Italy. During a mission in Tuscany, a squad is mercilessly attacked by the Nazis while crossing a river, and only a few survive. Those who do take cover in an abandoned farmhouse, where two soldiers (played by Michael Ealy and Omar Benson Miller) stumble upon an orphaned Italian boy. As they seek refuge in a nearby village, Miracle at St. Anna quickly builds into a multigenre epic—war movie, mystery thriller, action flick, character study, docudrama, and passion play. Lee spins a film steeped in the neorealism of Roberto Rossellini and the magic realism of Frank Capra, but ultimately it’s just the director at the top of his game.

Rubbing his eyes and drinking coffee—literally having just gotten off the red-eye from Los Angeles—Lee sat down with me in Chelsea, at Soundtrack f/t, where he was doing the final mixes on the film. Here he muses on everything from the Miracle at St. Anna to the miracle of Barack Obama.

BARRY MICHAEL COOPER: What’s up, man?

SPIKE LEE: B-Money, what’s good?

COOPER: Grits and gravy. Yo, man, Miracle at St. Anna . . . a masterpiece.

LEE: Thank you.

COOPER: For, like, five minutes at the end of the film, I was trying to hold ’em back. You killed it. Tell us about why you made this film.

LEE: It’s a World War II epic. It was adapted from the novel of the same name. When I read the novel, I knew it was a film I wanted to make. This was a chance to tell the story of all the brave

African-American soldiers who fought and died for this country during World War II. James McBride interviewed quite a few black men who are now in their seventies and eighties, who served in the Army and the Marines during the war. The title of the book is derived from the real-life massacre of the women, children, and elderly in the village of St. Anna di Stazzema on August 12, 1944. They were shot, and their bodies were burned. We actually filmed the scene at St. Anna—it was an eerie experience.

COOPER: How so?

LEE: Well, similar to when I shot the assassination scene in Malcolm X, with Denzel Washington playing Malcolm X, when production began, morale was very high. And as we got closer to the assassination, morale dropped. The same thing happened when I shot the massacre for Miracle. It was almost as if we could feel the ghosts of the place. It was unsettling and a little overwhelming.

COOPER: This film reminded me a lot of the films of Roberto Rossellini, especially Open City [1945], which, I believe, he filmed right after the Allied forces drove the Germans out of Rome in 1944. Did Rossellini and the neorealist movement have any impact on this film?

LEE: Absolutely. First and foremost, McBride wrote an incredible novel and script. So the power of the story began on the page. But definitely Rossellini’s Open City, Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves [1948], and Miracle in Milan [1951] all had a great impact on how I wanted to film this story. Martin Scorsese, who has one of the most extensive personal film libraries ever, gave me suggestions on films I should watch as I was scouting locations in Tuscany. We had dinner one night, and he told me that the natural light in Tuscany was beautiful and to be sure to make use of it there. Marty also gave me a lot of DVDs to watch, including a Rossellini film, Germany Year Zero [1948]. And those movies gave me a deeper perspective on how I wanted the story to feel. Marty has been a real friend and a great help to me over the course of my career.

COOPER: I felt a real connection to all of the characters, how the soldiers knew they were in an alien land, and how they knew they were fighting a war for a country that would treat them lower than second-class citizens when they came home.

LEE: All the spiritual aspects are right from the novel. James wrote a wonderful book.

COOPER: I didn’t realize until midway into the film that actor Michael Ealy’s character, Bishop Cummings, was an actual preacher back in the States. He acts almost angry at the Lord.

LEE: He’s really angry at the whole world. Bishop does not want to be there. In the scene where he and Derek Luke’s character, Aubrey Stamps, are talking, Stamps talks about how if they fight for their country and show America how black men are willing to fight and die, then maybe that will make it better for their children and grandchildren and future generations. Bishop disagrees, saying he doesn’t want to be there, “fighting the white man’s war. This is white folks’ stuff.” Many black World War II vets felt that going to Europe and the

Pacific and fighting on behalf of the Red, White, and Blue would convince white America that blacks were worthy of their long-overdue equality and that, upon their return, they would not be treated like second-class citizens anymore. And, of course, that was not the case. They should have known that already from what happened with the Olympic legend Jesse Owens. Jesse smashed those Nazi athletes in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. When he won the gold, Hitler wouldn’t even shake his hand. Jesse Owens was an American hero who showed the world that the Aryan race was not the “super” race. However, when he got back to the States, he had to run against horses. That’s a disgrace.

COOPER: Have you thought about the timing of Miracle at St. Anna being released around the same time Barack Obama might possibly become the next president of the United States?

LEE: I don’t think there are any accidents. Me and Tonya [Lee’s wife, attorney and author Tonya Lewis Lee] interviewed Michelle Obama for Trace magazine, and one of the things we talked about was the effect of Barack’s becoming president. Michelle told us that she is already getting reports of young black boys doing better in school and just a profound effect across the board. I hope the reality of Barack’s being the Democratic nominee lays down the gauntlet for African-Americans. I think when he takes that oath to become president of the United States of America—the first African-American president of this country—and he puts his hand on the Bible and swears to God, I believe all African-Americans in this country will have to take the same oath. We gotta step it up. Everybody, across the board. I don’t care if you’re a doctor, sanitation worker, teacher, rapper, filmmaker, athlete, mother, father, student. I think that we should all take the same oath. Everybody has to step up their games. This is too important. We should use an event like Barack’s presidency, which I feel is probably one of the most important moments in the history of this country, to galvanize us, to inspire us, and, yo, let’s go! And I hope this film falls right into that. I believe artists have to lead the way. The same way as in the turbulent ’60s: Sam Cooke made “A Change Is Gonna Come,” Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions have “We’re a Winner” and “People Get Ready,” and all of Stevie Wonder’s work—that music reflected both the difficult times we were going through and the enthusiasm and optimism we had, too. And I think Obama is going to have the same effect on African-American artists—and it’s needed.

COOPER: Is Barack Obama the product of a Spike Lee Joint?

LEE: No. Barack Obama is the product of Dr. King, Malcolm X, A. Philip Randolph, Marcus Garvey, Fannie Lou Hamer, Shirley Chisholm, Jesse Jackson—we can’t discount Jesse’s running for president, no matter what—and Al Sharpton. That’s who Barack is a product of.

COOPER: Is this country ready for a black president?

LEE: Yes.

COOPER: Why?

LEE: Bush. Bush has helped more than anything. The last four years of Bush have been like, “Fuck it. Let’s try something else, even if he is black.” But what’s really happening is these young kids today, these young white kids listening to hip-hop. And they don’t have this “thing” their parents had. Not to say that racism and prejudice are completely gone, but this whole multicultural thing is real. And that’s what has galvanized this whole Obama thing: the youth. The Clintons didn’t see that coming. That Internet shit kicked their asses, and that’s how the Obama campaign raised all this money. The whole world is watching this thing. And America is going to be looked upon as we were post–World War II—as the leader of the free world, instead of as the warmongers we’ve been the last eight years under the Bush administration. This is a new day, and I think this film fits right into that.