NYFF

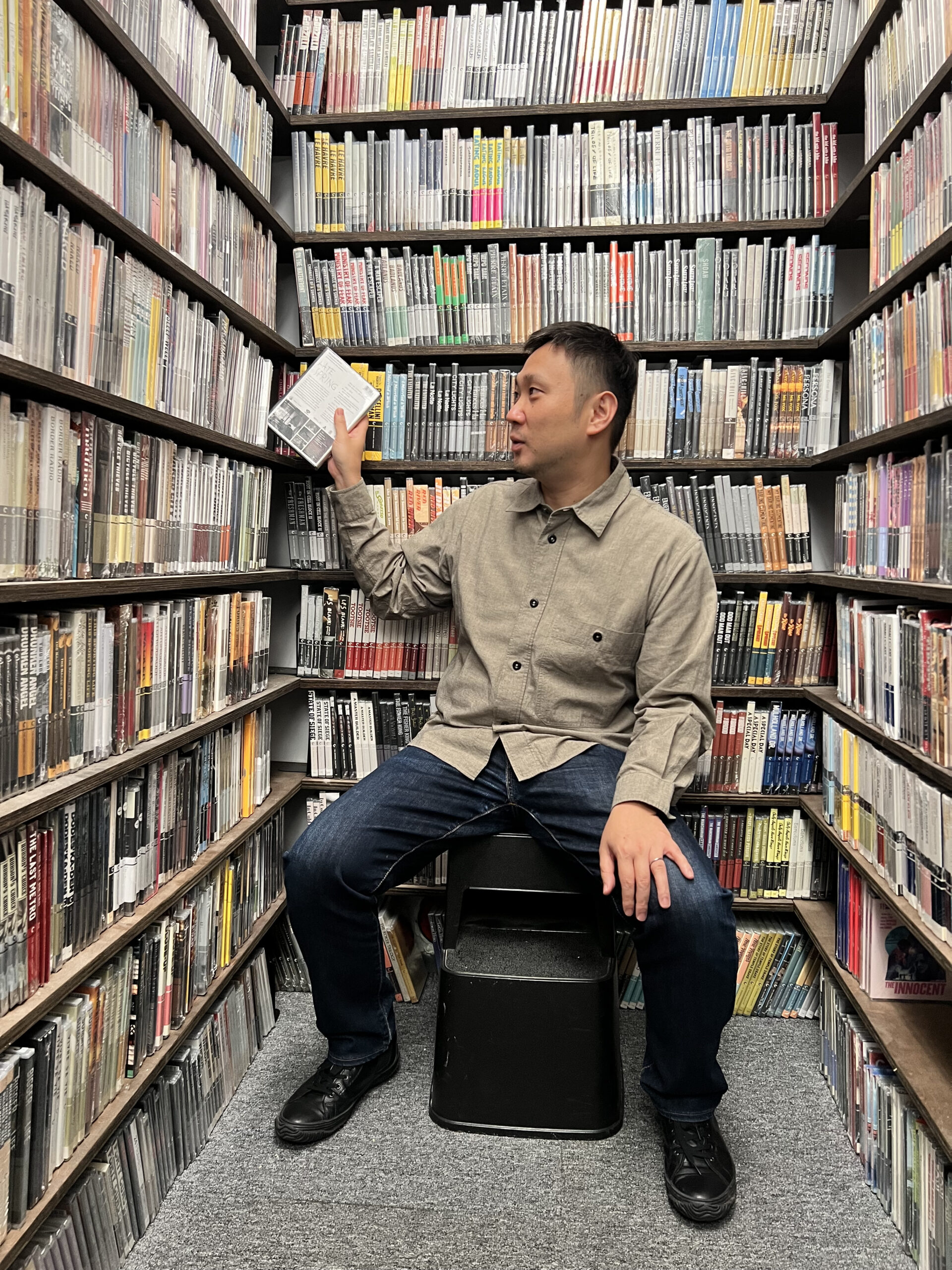

Ryusuke Hamaguchi and Jeremy O. Harris Link Up in the Criterion Closet

The poetry at the heart of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s films is often the poetry of the mundane: a missed connection, the chopping of a log, drinks out with colleagues. In his latest film, Evil Does Not Exist, this poetry is juxtaposed with a politic meant to unnerve us like a chill to the spine to the realities of how quickly capitalism is eroding not just our ecology but also our hopes for a future.

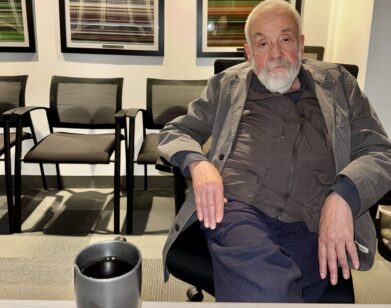

In the quiet Criterion offices in midtown, Hamaguchi and I spoke with the help of his whip smart translator, Monika (another gemini), about his work. Throughout the conversation we covered Scandavian playwrights, the limits of language, how film can fill the gaps, and if, or more precisely when, Japan’s most exciting new filmmaker will make his first English language feature.

———

JEREMY O. HARRIS: I am so in love with this film.

RYUSUKE HAMAGUCHI: Thank you very much.

HARRIS: You continue to astound. And the fact that you’ve only been doing these narrative feature films for a decade. You were so lauded for your first film, and that was a decade ago. You’re the third Japanese director to be nominated for an Oscar for Best Director, and very much a darling of Japanese cinema right now. How does that make you feel? Were you expecting this when you first started making docs and features?

HAMAGUCHI: First, I just want to thank you for knowing so much about my history. Of course, I can’t say that I was expecting any of this. From my perspective, I just want to diligently be able to continue my work. The reception, of course, is very surprising. On the other hand, I do feel like there’s a certain kind of progression in my career, and I am very thankful and accept any kind of reception towards my individual works.

HARRIS: One of the things that often happens when a director of your caliber from the international world starts to experience this sort of Western or American excitement is that people start knocking for you to do an English language movie. Is that on the horizon?

HAMAGUCHI: Yeah, I have received those kinds of offers, and it’s something that I’m very interested in. I’m actually curious to know how you work in a different language from your own language. The one thing that I worry about is kind of an inexactness that might emerge from directing someone in a language other than my own. So, if this were to happen, I think it would need to be very gradual, and maybe a work that actually includes Japanese as well.

HARRIS: Yeah. On my end, it was quite curious watching a play that was written for a Black American lead be done with fully native Japanese actors in Japan, and how much of the identity-based meaning-making that I thought was necessary got eroded there. What was very heartening was that so much that happened in the English production just naturally translated so well inside of this Japanese cast that I felt like I was watching my play, but as if I was on Netflix and just changed language. Misuzu Ozone played the mother, and she’s phenomenal. If an actor is great, I think they’ll channel the author’s intentions.

HAMAGUCHI: It’s very important, the kind of actors that you’re able to work with.

HARRIS: Yes. You are so interested in theater, and it makes you very happy. I’m obsessed with Asako I & II and Drive My Car. And now, Evil Does Not Exist. So many of them have this sort of love affair with Chekhov. Where did that start? Were you always a theater maker, a theater watcher?

HAMAGUCHI: It’s not that I was actually interested in theater specifically. I was interested in movies that incorporate theater. For instance, Jacques Rivette, or [John] Cassavetes, even Frederick Wiseman’s documentaries on theater. What I really enjoyed and felt so comfortable with in these types of films is that, in general, you see acting as a hidden and inconspicuous gesture, but in theater it seems like it’s revealed in a different way. They’re acting and they’re not pretending like they’re not acting. That’s where I started to be interested in Chekhov. I get asked a lot about Chekhov, actually. I do see plays, but I’m going to be very honest. I’ve seen stagings of Chekhov plays in Japan, and I’ve never actually thought they were very interesting. Finally, I read his plays, and it was as if I was being punched by every single word. It really, really resonated with me. But I have to say when, in Asako I & II, I drew from a line of Chekhov’s play, I didn’t even know that was a very famous line. I just incorporated it because it resonated with me.

HARRIS: I love that. Chekhov and Stanislavski were really trying to find out how humans are most honest with each other, and how honest they are by themselves. I feel you have this similarity to them, so I’m curious what you’re trying to learn about [in your work]?

RYUSUKE HAMAGUCHI: It’s really a complex intersection of ideas, but earlier I mentioned reading Chekhov and feeling punched by each of the words. It was really that I was sensing each character’s true emotions, that it was their guts emerging out of these words. Something I realized was that it’s just a series of monologues, that each character isn’t really thinking about the other people, compared with someone like Ibsen, who feels much more about dialogue. In Chekhov, it feels like it’s just a series of monologues, and that’s something that I thought about and was trying to incorporate in a movie like Drive My Car. And, just to go back to my interest in the theater, I think that there’s a certain kind of emotion that can’t be reached unless through the act of acting. It’s like being lied to, but in the framework of theater, the audience is very willingly participating and very supportive of creating that environment in which they accept this act. So, when you think of melodrama, and the fiction and false nature of melodrama, you can think of theater in the same way, how there’s this very active participation of the audience that has this willingness to believe what is happening on stage.

HARRIS: I feel like I’m about to cry because your artistic mode is so in line with my own, and I feel very seen by this. Also, you’re an amazing translator.

MONIKA UCHIYAMA: Oh, I appreciate it so much.

HARRIS: I know translators are supposed to be invisible, but I’m going to talk about you because you’re very, very good. Ryusuke, what is your relationship to having your words constantly filtered through translation?

HAMAGUCHI: It is a complex problem. Before I became a director, I was a cinephile, and what it means to be a person watching and receiving films in a language other than my own means is to be reading subtitles. And I’ve been moved by subtitles. I think my overall perception of translation and subtitling itself is very positive. Because I understand quite a bit of English, I’ll watch my films and read the English subtitles, and I understand that there is no real way to make a very direct and literal translation. There’s no way to transfer its true meaning in Japanese into another language. But one thing about films is that there are two things that never disappear, the image and the audio. So, when you’re watching the image, it could be about the body movement of the actor, or even when an actor is standing very still, the very small gestures. Those are all received. The voice is always directly received by the audience, even if the words are not. So, if you read a subtitle and 80 to 90% of the meaning is intact, the rest can be directly received through the quality of the voice and the movements. And I think that because subtitles and translation can act as a bridge for this understanding, all I feel is a very deep gratitude towards it. Something that [Haruki] Murakami said is that there has to be a very deep belief that I myself am capable of translating this work, that I can create this intimate tunnel between these two works, that I am the right person to understand this work. I think that that belief is very similar to acting. I write a script, and the actor receives this fictional character. And that character can be very different from the person that the actor is, but that actor needs to have that confidence and belief that they’re the right person to be acting [the part]. And there are going to be small changes or transformations that happen between what’s on the page and the actor, and that’s very similar to translation.

HARRIS: I love that. You mentioned Ibsen. That made me very happy because as I watched Evil Does Not Exist, I was like, “This is his Ibsen moment. This is an adaptation of Enemy of the People.” Was that at the top of your mind?

HAMAGUCHI: I’m quite embarrassed to say that I actually hadn’t read the play before. And when I screened at Venice, I was asked over and over again, “Have you read Enemy of the People?” And I said, “No, I haven’t.” There wasn’t any recent translation in the last 70 years in Japan, so that’s my excuse, but I did see a similarity once I read it. In fact, when I think about it, I would say that my true sensibilities as a writer are closer to Ibsen rather than Chekhov. I’m not really trying to isolate each character’s characteristics or perspectives. I’m more interested in the honest human nature that emerges through relationships.

HARRIS: Are there any Ibsen plays that you think you’d want to visit?

HAMAGUCHI: Ghosts.

HARRIS: Ghosts is amazing.

RYUSUKE HAMAGUCHI: Yes. I really love that play. I think about how so many of Ibsen’s plays have to do with truth as a very destructive thing, that truth actually has the power to destroy societies.

HARRIS: Yes. Okay, I’m going to ask a really quick question about your relationship to music. How did you come to this score? As you were doing some of these long takes, were you thinking, “Oh, this will be symphonic once I add the score”?

HAMAGUCHI: I would say that the way the music matches with the images was quite coincidental. There were things that I knew in advance. For instance, the main theme that you hear recurring throughout the film, I knew that needed to go in the beginning, and I also knew that it needed to go at the end. But because this is a film that incorporates a lot of music and is built around it, it was really just about trying to place different score elements with the scene and then just seeing what clicks into place. Ishibashi Eiko, who did the score, her pieces have a lot of points where there’s this kind of matching and clicking into place. And searching for those moments was one really exciting part of editing the film. I think that it allowed me to use a lot of music throughout the film without going overboard. It just feels like a very appropriate marriage of music and image. I wanted to ask a question, though. Have you ever done an adaptation or staged any Ibsen or Chekhov?

HARRIS: I’ve never adapted Chekhov or Ibsen. I’ve adapted Brecht. I’m a bit loud. I want to get to the quiet of Ibsen and Chekhov, but I haven’t yet. One of my very good friends, Amy Herzog, just did an amazing Ibsen adaptation of A Doll’s House with Jessica Chastain. And Annie Baker, who has a movie here, and who’s sort of America’s new Chekhov, has a really great adaptation of Chekhov that I love. And then Ibsen is that bitch. Ibsen is a dramatist. He gives us scenes, he gives us stakes, and it’s so hard to find that in so many contemporary writers.

HAMAGUCHI: It’s interesting everything that you said about both Chekhov and Ibsen, particularly about Chekhov, that they’re very funny when staged properly. I think that that contributes to the fact that I haven’t really been very interested in stagings that I’ve seen in Japan. And perhaps that’s an issue of translation.

HARRIS: That’s an issue in America, too. Americans can’t do Chekhov.

HAMAGUCHI: There are just very few directors who are able to interpret Chekhov in a way where that funniness is preserved, although I’ve seen a few interesting attempts. And as far as Ibsen, I agree with you completely. Every time I see an Ibsen play or read an Ibsen play, I just think, “What a horrific story.” But through that horror emerges a certain kind of truth, and I think that that kind of work is really difficult to do today. That’s something that I would like to challenge myself to do.

HARRIS: They’re going to kick me out, but two more things. Have you seen “The Bear” or “Normal People”?

HAMAGUCHI: I’ve heard of them, but I haven’t seen them.

HARRIS: Paul Mescal and Ayo Edebiri are two of my favorite actors right now. I think if you did a Haneke-style shot-for-shot remake of one of your movies, I’d want to see them in Asako I & II.

HAMAGUCHI: Oh, would you like to produce it?

HARRIS: I will produce it. Literally, if you want to sign the papers, I will do it right now. It’s my dream.

HAMAGUCHI: Thank you.

HARRIS: This is your second time at the New York Film Festival. What is your favorite thing to do in New York?

HAMAGUCHI: I go to The Metropolitan every time I’m here. The great thing about the Met is that it’s really impossible to see the whole thing, and I think that New Yorkers are so lucky to be able to go for free.

HARRIS: It’s amazing. This has been such an honor.

UCHIYAMA: Can I say something ridiculous?

HARRIS: Yes.

UCHIYAMA: You’re my celebrity birthday twin.

HARRIS: Oh! You’re June 2nd as well?

UCHIYAMA: June 2nd.

HARRIS: Andy Cohen is also June 2nd.

UCHIYAMA: No!

HARRIS: It’s insane.

UCHIYAMA: We’re an evil bunch.