Roger Corman

I LIKED THE LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS, BECAUSE IT IMPLIED A HORROR FILM, BUT IT ALSO IMPLIED THAT THERE WAS GOING TO BE HUMOR IN IT—IT WAS GOING TO BE SOMETHING DIFFERENT. I WAS SORT OF AIMING AT TWO DISPARATE AUDIENCES AND BROUGHT THEM TOGETHER WITH THAT TITLE.ROGER CORMAN

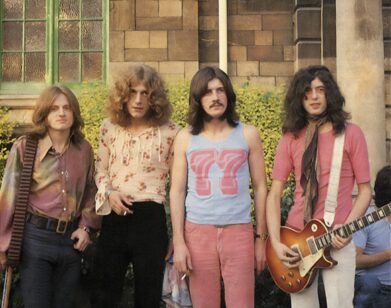

There are few players in Tinseltown who could write an autobiography called How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime and stand behind it as a statement of fact, but Roger Corman—sensationalist auteur, visionary of the drive-in flick, legendary B-movie kingpin—is most definitely one of them (and yes, he actually did write that book). As a director and producer, 88-year-old Corman is responsible for bringing literally hundreds of horror, sci-fi, and sundry exploitation films to the screen, many of which would go on to become classics, both cult and otherwise. During the early ’60s, Corman gloriously adapted more than a half-dozen of Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous stories with star Vincent Price. And while regularly turning out movies like She Gods of Shark Reef (1958) and A Bucket of Blood (1959), he also managed to whip together a soon-to-be-famous, low-budget thriller called The Little Shop of Horrors (1960)—a movie shot in just two days that introduced the world to a man-eating plant named Audrey. Corman’s rapidly expanding cinematic universe—a place populated by the undead, teenage cavemen, haunted houses, swamp women, wasp women, a great number of very busty women, gunslingers, and a variety of hastily assembled and not terribly terrifying monsters—also provided an unwitting reflection of the times. As the ’60s gave way to the ’70s, Corman’s productions increasingly reflected the growing counterculture. Movies like 1967’s drug odyssey The Trip (written by Jack Nicholson and starring Peter Fonda, Bruce Dern, and Dennis Hopper) were unwitting testaments to the LSD-soaked psychedelia and feelings of alienation and dread that seemed to dominate youth culture toward the end of that decade. Such wily cultural prescience—whether intentional or not—was on display in much of Corman’s output. In The White Album, Joan Didion recalls going to see Corman’s 1966 biker epic The Wild Angels (a film whose tagline reads: “Their credo is violence … Their God is hate … And they call themselves ‘THE WILD ANGELS’ ”) because “there on the screen was some news I was not getting from The New York Times. I began to think I was seeing ideograms of the future.”

Through his association with American International Pictures (a studio specializing in quickly produced, low-budget films) and, later, through his own independent film studio, New World Pictures, which he fronted from 1970 until it was sold in 1983, the Detroit-born Corman not only produced and directed a dizzying variety of films, he also gave jobs to a veritable who’s who of actors, producers, and directors who would later go on to become cinematic power players. Everyone from Ron Howard, Curtis Hanson, Joe Dante (who directed the 1978 cult classic Piranha for Corman), Martin Scorsese, and a young upstart named Francis Ford Coppola all got their formative breaks via a Corman production. It was also through Corman’s New World studio that a young writer and producer by the name of Jonathan Demme was able, in 1974, to distribute his directorial debut, a sordid classic in the much-maligned genre of “women in prison” films called Caged Heat. Eventually Demme would go on to much greater things, including picking up a best director Oscar for 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs (in addition to making what is arguably the greatest concert film ever made, Talking Heads’ 1984 masterpiece Stop Making Sense), but back in the early ’70s, he was still a newbie looking to make a name for himself, a feat largely facilitated by working with Corman. Last December, Demme spoke to his old friend by phone—Corman was in his office in Los Angeles, still working tirelessly as a producer at New Horizons Picture Corp. (His upcoming project for television, Sharktopus Vs. Mermantula, a sequel to 2010’s Sharktopus, proves there is still very much an audience for his classic monster vehicles). The two reminisced about the old days and talked about the one thing they both still love the most: movies.

JONATHAN DEMME: Roger!

ROGER CORMAN: Hello, Jonathan!

DEMME: How did they lure you into being interviewed for Interview?

CORMAN: I have no idea. [laughs] And I don’t know how they lured you!

DEMME: Okay, Roger, there obviously aren’t going to be any softballs lobbed your way here; it’s all going to be pretty hardcore questions.

CORMAN: Right, hit me with some hard ones.

DEMME: I’d like to start off with the following: You used to say that in order to succeed, a director had to be 40 percent artist and 60 percent businessperson. Does that still hold true for you, and if so, how did you come up with that formula?

CORMAN: The formula was made up. I would actually modify it now, although the business side seems to have taken over motion pictures. I would probably make it 50-50. Half artist, half businessman.

DEMME: Why does one have to be a businessperson in order to make a good picture?

CORMAN: For one thing, you have to go back a little bit into history. Say there were playwrights, there were painters, there were composers—all of these people could work by themselves and create a work of art. I think one of the reasons movies are the quintessential modern art form is that it is partially a business. The director needs a crew—the writer, the producer, etcetera—and to have that, he needs money. In order to create art today, you have to compromise your art somewhat and be a businessman.

ONE OF THE REASONS MOVIES ARE THE QUINTESSENTIAL MODERN ART FORM IS THAT IT IS PARTIALLY A BUSINESS. IN ORDER TO CREATE ART TODAY, YOU HAVE TO COMPROMISE YOUR ART SOMEWHAT AND BE A BUSINESSMAN. ROGER CORMAN

DEMME: Maybe that’s where the new art comes in—to somehow have your eye on the marketplace and harness your art to come up with something you can be proud of creatively. Did you ever see that Robert Aldrich movie The Legend of Lylah Clare [1968]?

CORMAN: No, I didn’t see that film, but I saw an Aldrich film about Hollywood. I forgot the name of it, but it portrayed the combination of art and business brilliantly.

DEMME: I think that film was probably The Big Knife [1955], right?

CORMAN: Yes. Exactly.

DEMME: Obviously Aldrich thought a lot about this kind of thing, because in The Legend of Lylah Clare, there’s this great exchange where Peter Finch is playing a very auteurist director, probably modeled after Josef von Sternberg, and Ernest Borgnine is playing a crass studio chief. Finch rails at all these philistine restrictions that are being placed on the director and what a low form of life these studio heads are. Ernest Borgnine tells him, “Without me, bums like you would be making homemade movies for an audience of one.” [both laugh]

CORMAN: Exactly. Someday I’d like to see a picture made about a sensitive studio head.

DEMME: Well, you know that would probably be your self-portrait, right?

CORMAN: I’d be somewhere in between. We’ll split the difference there.

DEMME: Speaking of you as a character, I’ve heard about Joe Dante’s new picture, and it thrills me. Is he really making a picture about you called The Man With Kaleidoscope Eyes?

CORMAN: Yes. It’s a picture about me when I made The Trip, and about The Trip. That movie had all kinds of psychedelic shots in it, and we used some old kaleidoscope lenses for certain sequences, thus the title.

DEMME: It’s a brilliant title. I know that Joe is going to make an extraordinary film. Who can play you, though?

CORMAN: His first choice was Colin Firth, which I thought was a great choice, and Colin seemed to be interested, but after he won the Academy Award, his price probably went up. I don’t know who he’s going to go with now.

DEMME: My hope for this film would be that it contains a good degree of sex, some violence, a bit of nudity, and perhaps a subtle social statement.

CORMAN: I have never objected to that formula.

DEMME: [laughs] That is something we had to understand when we were making pictures for New World, and I think some may have bristled at that. For me, it was fine because I loved all of those ingredients. Later, as one gets older and starts noticing all the other movies that are made, especially the successful, big-budget pictures that come out of Hollywood, it’s like, “Well, what do you know! They’ve got the Corman formula too.” You were always one of my favorite directors, whether you were working with a low budget or a higher budget. Whether it was A Bucket of Blood, which had its own extraordinary cinematic values or it was one of the best gangster pictures ever made, The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre [1967], it’s obvious in all your films that you are an intuitive, excellent director. But it seems as if a moment came where you made a choice and you essentially turned your back on directing. You have made a couple of other pictures, but it would appear that you exchanged showing up on set and doing all of the stuff a director does for being the supervisor behind lots of pictures. My fantasy is that you thought, “You know, directing is great fun and you can get a lot of fulfillment from it, but in terms of being able to really, really earn a living in America today, it’s a waste of my time to focus my energy on one picture. I would rather be enormously successful financially and get my creative fulfillment vicariously as a producer.” Do I have any of this correct?

CORMAN: That was the second part of the decision. The initial part of the decision was that I was shooting a picture in Ireland called Von Richthofen and Brown [1971], and I just became tired. I had directed more than 50 pictures in 15 years. I remember one time I was shooting a picture during the day, casting another picture during the lunch hour, and editing the previous picture in the evening. At that point I realized it was out of control. On Von Richthofen and Brown I was just so tired I thought, “What I’ll do is I’ll just finish the picture”—which I did, although I was so tired I barely managed to—”and I’ll take a year off and rest.” Then I got bored and I started New World Pictures. I became, as you say, sort of a producer and a supervisor of films. I found that role to be very fulfilling, and one thing led to another and I just didn’t go back to directing because it was so fascinating to be involved with all of these different aspects of filmmaking.

DEMME: Did you also get fed up with having to answer to the guys at AIP [American International Pictures], and hearing what they had to say about your work? I figured you just felt you could do what they were doing better anyway, and it would be great to remove that kind of bullshit from your life once and for all.

CORMAN: It was partially that. I did The Wild Angels and The Trip for AIP. The Wild Angels was the opening-night picture of the Venice Film Festival and was also commercially successful. I think The Trip was the only American picture invited to the Cannes Film Festival that year and was also successful. They made small cuts on both pictures that probably today I wouldn’t worry about, but I just didn’t like the idea that they had tampered with my films after I’d finished them. I thought, “When I’ve got my own company, nobody can come behind my back and do anything.”

DEMME: That’s kind of amazing, especially when one imagines the people who were making those cutting determinations, but that’s still going on all over the industry. You have worked for many years with your wife, my good friend Julie Corman, and I sort of feel that Julie has influenced you both as a producer and as a distributor.

I JUST DIDN’T LIKE THE IDEA THAT THEY HAD TAMPERED WITH MY FILMS AFTER I’D FINISHED THEM. I THOUGHT, ‘WHEN I’VE GOT MY OWN COMPANY, NOBODY CAN COME BEHIND MY BACK AND DO ANYTHING.’ ROGER CORMAN

CORMAN: I’ve grown to depend a little bit upon Julie. She did her first film with a whole lot of help from me, but on her second film she took over and was truly her own person as a producer. One of the major things she did for me and for the company was that she started making family films, which we had not made before. They were quite successful and brought us into a different area of filmmaking, and for the last few years we’ve been working together as partners, as co-producers, on the last few films.

DEMME: I wrote down a couple of questions. One is, what’s the best title you’ve ever come up with?

CORMAN: I’m not really certain. I like The Man With the X-Ray Eyes. It was actually X: The Man With the X-Ray Eyes. I thought that was a very evocative title. On the other hand, I liked The Little Shop of Horrors, because it implied a horror film, but it also implied that there was going to be humor in it-it was going to be something different. I was sort of aiming at two disparate audiences and brought them together with that title.

DEMME: Yeah, and I hope you’re reaping the rewards of all these manifestations of The Little Shop of Horrors, as it became a Broadway musical and was remade as another film. Did you make a nice deal for yourself on that?

CORMAN: I made a deal to get a certain percentage. It wasn’t as great a deal as it might be, because I thought it was just going to be a little off-Broadway thing and I was helping these young guys out. Maybe I should have been tougher.

DEMME: There was an off-Broadway play that is a satire of The Silence of the Lambs. I’ve seen it and it’s terrific. Most of us who were involved in that movie have seen it. They used all the lines from the movie and the performances are brilliant—all these great impersonations of the actors in the film. At first, we were just delighted that this was happening, we thought, “That’s terrific.” Then it moved uptown to a bigger theater and it’s become this gigantic hit. But, Roger, we’re not getting a penny from it. That just doesn’t seem right.

CORMAN: You were even nicer than I was. [laughs] But how did they do that without you getting anything out of it?

DEMME: I think it had something to do with it being in the category of “parody.”

CORMAN: Jonathan, I can recommend a couple of very good lawyers.

DEMME: I will get back to you on that. So you said before that you got tired of directing—physically tired of all the activity that went into the day. Do you ever get tired, as I do now, about having all of these ideas for movies?

CORMAN: I am having somewhat fewer ideas. Maybe it’s just a matter of getting older and being aware that the market for medium-budget and low-budget films, which is of course what I spent most of my life making, has diminished. And maybe the quality—I don’t know if quality is the right word, I meant to say quantity; you can figure out later the Freudian reason for saying that—maybe the quantity of ideas has diminished a little bit. I still have a couple of good ones, but I’m aware of how difficult it is in today’s market to even get a picture made. It’s easier for us because we’re an independent company and we’re low budget, but we’re aware just how bad the market is and most pictures are losing money. So I turn down most of my ideas on the basis that I have to be fairly certain that I’m going to have a success.

DEMME: Going back to titles for a second. My favorite title of yours is a film that started out being called The Intruder [1962].

CORMAN: Oh, yes.

DEMME: By the time I saw it, it was called I Hate Your Guts.

CORMAN: That was unfortunate. What happened was that The Intruder went to a number of festivals, including the Venice Film Festival, won awards at a couple of minor festivals, got wonderful reviews, and then failed commercially. And a guy I knew who distributed films primarily in the South to drive-ins said, “Let me take a shot at re-titling that picture.” He put that new title on it. I would almost say that it’s fortunate that it didn’t succeed with that title either, so that title faded away. If the picture would have succeeded with that title, I’m not certain I would have been pleased.

DEMME: Fair enough. Did you recently make a film titled something like Sharknado?

CORMAN: No, I did not. That was made by another company, but it got a whole lot of publicity. I had made a picture with an equally insane title called Sharktopus.

DEMME: Yeah!

CORMAN: I don’t often mention that title, Jonathan, but it was a huge success.

DEMME: Sharktopus! Wow, that’s just wonderful. In the New World days, I was under the impression that sometimes you would float a title to the distributors and the exhibitors, and if enough of them expressed excitement about the title, then you’d go ahead and have the script written and get the picture made. Is that accurate?

CORMAN: That was true with the very first picture we made, which was The Student Nurses [1970]. We had nothing but a title and I didn’t have much money then, so I talked to some independent distribution people about putting money into the picture based only on that title. That was the title that really got New World Pictures started.

ONE TIME I WAS SHOOTING A PICTURE DURING THE DAY, CASTING ANOTHER PICTURE DURING THE LUNCH HOUR, AND EDITING THE PREVIOUS PICTURE IN THE EVENING. ROGER CORMAN

DEMME: I remember those days well. I was just so lucky to have had anything to do with you and New World Pictures, but specifically to have been a producer in the first wave of pictures that came out of New World. There was Student Nurses, and I know Curtis Hanson was making a movie there during that time …

CORMAN: And you were in the Philippines doing great work for us, I remember.

DEMME: Yes, The Hot Box [1972]. And I worked on the Hells Angels movie before that [Angels Hard as They Come, 1971]. There are just so many. You also had women directors working for you at a time when I don’t think there were any women directors working on the Hollywood scene. You had Barbara Peeters making movies. George Armitage made a number of terrific pictures, and Joe Viola directed the first ones that I wrote and then produced. It was thrilling for us to just be a part of New World Pictures, but was it stressful for you? Having the considerable audacity to open up your own distribution company, to finance your own pictures, was it exciting or stressful?

CORMAN: It was a little bit stressful, but at that young age maybe you thrive on stress. It was exciting, too. Our first picture, The Student Nurses, was directed by a woman named Stephanie Rothman, then Jack Hill did our second picture, which was called Big Doll House [1971]. Both of these pictures were very big successes, and in something like six months we were being recognized as a strong independent company. I was a little amazed. That was one of the reasons I didn’t go back to directing. I originally thought I’d probably go back into directing after getting this company started, then the thing took off and I just went with it.

DEMME: It was a good trap because you were so successful with it. But eventually you did direct again. You made Frankenstein Unbound [1990].

CORMAN: Yes, that was the only picture I directed after I started New World, and it was something like 20 years since I had directed a picture. I wondered how it was going to be, but then I got out on the set and I thought, “It’s the same as it always was. I’m just working again.”

DEMME: It’s a beautiful picture. It’s sad to have someone as gifted as you turn your back on making more movies, so it was very exciting when Frankenstein Unbound came out and great to see how strong it was. Will you ever direct another?

CORMAN: Every now and then I think that I would do it again. It could be a picture I really loved and wanted to make, or maybe it could just be the next script that came off the assembly line.

DEMME: That would certainly please any number of film buffs and moviegoers. This is that time of year when everybody is playing the “Have you seen such and such” game. Have you been trying to stay abreast of all the new pictures?

CORMAN: A little bit. I’ve seen three pictures recently I liked very much. I liked Gravity, which starred Sandra Bullock, who actually did one of her first pictures with me. I thought Gravity was very good. I saw the Tom Hanks picture, Captain Phillips. I’ve had the pleasure of working with Tom as an actor as well. Recently Jack Nicholson had a screening of Alexander Payne’s picture Nebraska, which stars Bruce Dern, and I also liked that picture very much, particularly because of Bruce. It was an interesting screening because Jack invited all of the old guys. Jack was there, Bruce was there, Peter Fonda, and we were like, “It’s like the ’60s—we’re all back together again!”

DEMME: Bruce Dern had a big part in The Wild Angels and a couple of other pictures that you directed, right?

CORMAN: Yes. The Trip and a couple of others. I know you’ve just finished a picture called A Master Builder, which I had the pleasure of looking at last week. I think when it’s distributed, it’s going to be a major success.

DEMME: Oh, thank you! We finished that very recently and took it to the Rome Film Festival and it got a very strong reaction there. As you know, it’s based on Ibsen, and especially with what folks go to see nowadays—and I go along with them—I thought, “Gosh, is there really room for a two-hour drama of people talking to each other?”

CORMAN: There should be, and for this film, I think there will be.

DEMME: You went through a period of your life where you raised these wonderful children, and now they are out of the house. They now have their own careers. Does that whole extended moment of hands-on parenthood now seem a little like a dream to you?

CORMAN: It almost does, although everybody came home for Thanksgiving just last week, and it was nice having everybody together. The two girls live in New York. Normally the boys travel and the girls stay home, but our two daughters came home from New York, so it brought a little bit of it all back together. One of them brought up when I was coaching their Little League basketball team long ago, and I thought, “I hardly remember that, but I remember how much fun it was.”

DEMME: Well, Roger, what didn’t I ask you that I should have?

CORMAN: I think you mentioned everything we can talk about in public.

JONATHAN DEMME IS AN ACADEMY AWARD-WINNING DIRECTOR. HIS FILM A MASTER BUILDER WILL PREMIERE IN NEWYORK IN JULY.