Archives

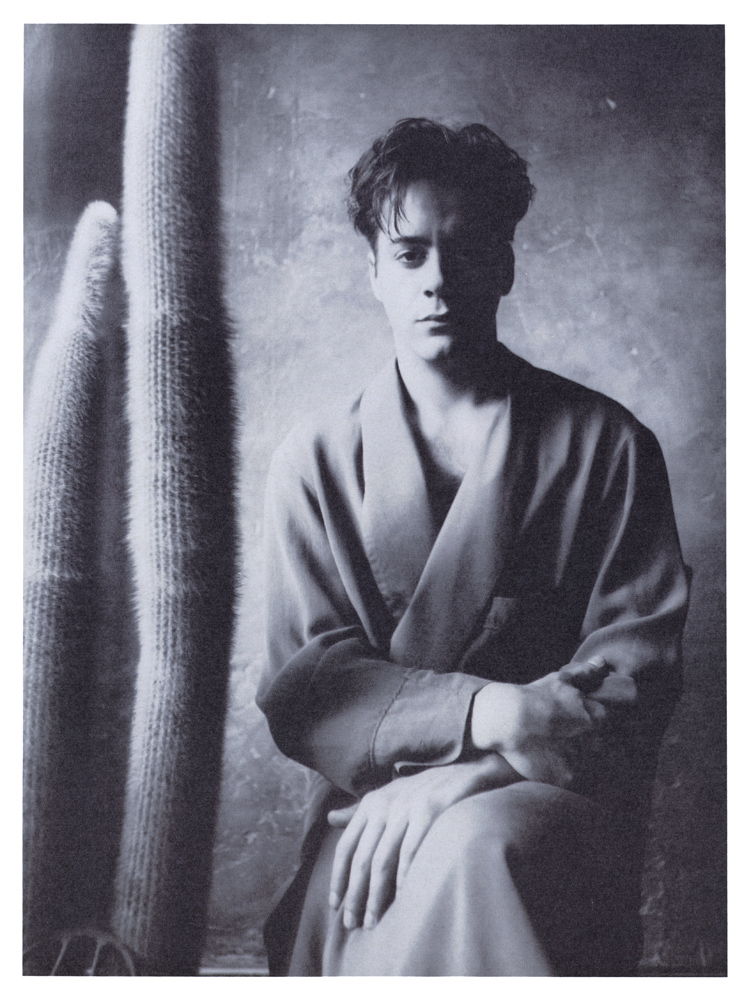

Robert Downey Jr. Has Always Wanted to Entertain

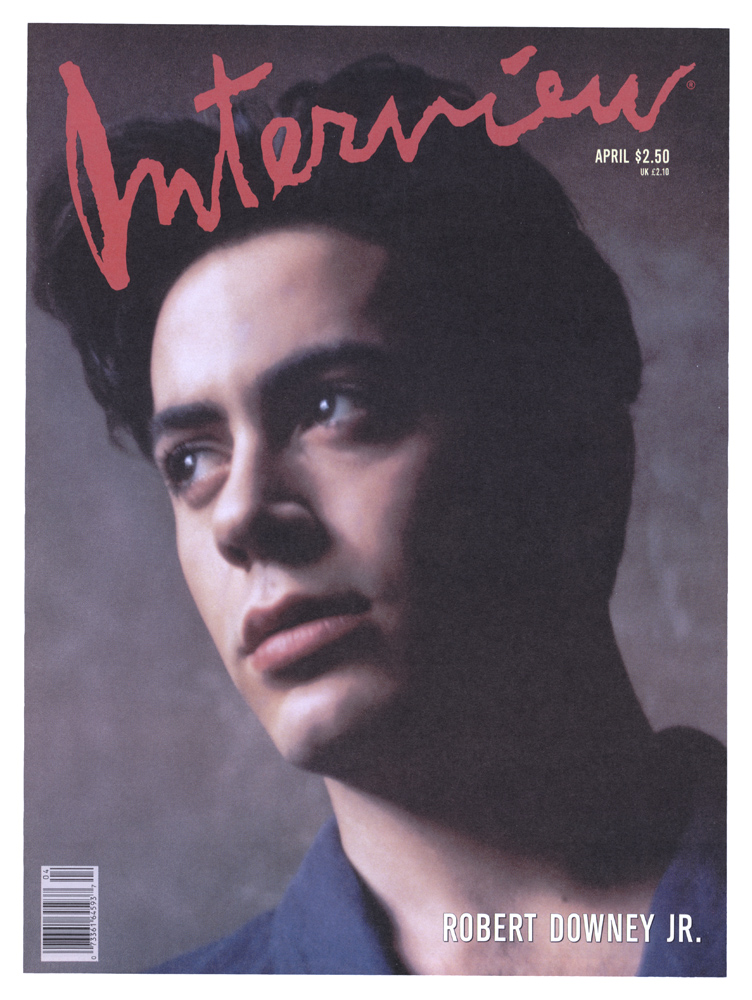

This week, we dip into the archives, all the way back to 1989, in celebration of the great Robert Downey Jr.’s very first Oscar win for Best Supporting Actor in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. In his 1989 Interview cover story, a 23-year-old RDJ hosts writer Kenneth Turan at a classic Hollywood house built for Charlie Chaplin, just a few years before his Oscar nomination for Chaplin. The wunderkind was searching for collaborators to resurrect a stagnating industry sleazing in wealth and artifice. “I think I was always someone who wanted to be entertaining or whatever, even when I was a kid,” Downey Jr. said. “But now you just start to realize that it’s pretty sad. Spending time by myself doesn’t have to mean having no one else in the house but just being able to slow down and have quiet times. I play piano, and that chills me out.”

———

Cinema Scion

By Kenneth Turan

The son of the maverick director of Putney Swope, Robert Downey Jr., at 23, is a veteran of 15 films. Kenneth Turan met with him in Los Angeles to talk about dropping out, selling out, and life on the run.

The house, pink and perfect, sits just a stone’s throw from the Sunset Strip. It’s classic Hollywood, reputedly built for one of the old legends of cinema, Charlie Chaplin. But ruling classes change, especially in the movie business, and its current occupant is one of the most sought-after new young actors, Robert Downey Jr.

Son of legendary rogue director Robert Downey (Putney Swope, Pound, Greaser’s Palace) Downey Jr. has not been shy about his work, appearing in 15 films in his 23 years, working with everyone from Molly Ringwald to George C. Scott. His performances have ranged from the startling effective, as in Less Than Zero, to the less memorable, as in The Pick-Up Artist and 1969. Still, his inimitable high-wire energy keeps everyone coming back for more. Most recently he could be seen in True Believer and Chances Are, which starts Ryan O’Neal and Cybill Shepherd.

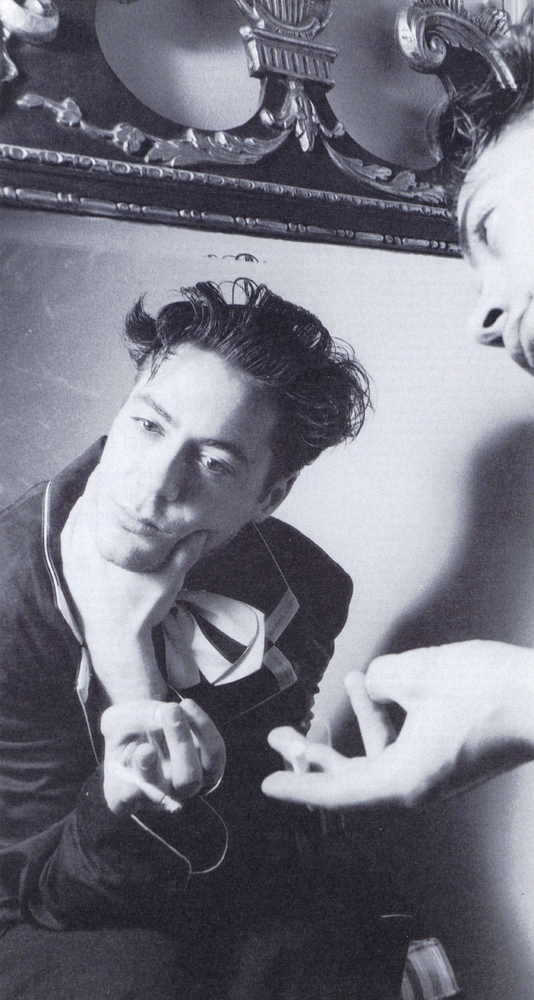

In person Downey is an appealing combination of sweetness and nervous energy. It’s fun being young and in demand, his demeanor seems to say, but perhaps not as fun as you think. He showed me around, played with his cats and on the bright red piano that sits in the front room, said hello to Judd Nelson (ensconced in a spare room), and tried to put me at ease, seemingly all at once. Wearing jeans and a white turtleneck, he settled in to one of the upstairs rooms and began to talk.

KENNETH TURAN: What is the history of this house?

ROBERT DOWNEY JR.: It was built by one of Cecil B. DeMille’s set designers for Charlie Chaplin, who lived here—or this was one of 90 places they built for him. I swear to God, you can go into a brand-new condo building and they’ll say, “Way back when, Barrymore…” It may be the same lot, but I don’t think they had track lighting in ’24.

TURAN: What position does Chances Are occupy in your body of work?

DOWNEY: Probably in the upper colon. No, it’s a nice film; he’s a nice guy, and he’s the most accessible character I’ve ever played. Now you’ll think I’m the person who’s in Chances Are, which is nice because he’s a nice guy.

TURAN: You were quoted as saying, “Cybill Shepherd taught me I don’t have to talk every minute.” Is there truth to that, or is it just something in the press kit?

DOWNEY: Well, I don’t think it was really phrased that way. I think it was more that she taught me to take my time. Because I got so used to playing characters who talk fast. In movies they take so much time setting up shots and stuff, and I understand they’re doing their thing. Some DPs [directors of photography] take an hour to light a cigarette. It’s O.K. to take your time, I’m not saying it’s all right to be self-indulgent, but that’s what you’re there for, and sometimes you feel hurried. Everything’s hurried so that you can go around and wait until they’re ready.

TURAN: Like hurry up and wait.

DOWNEY: Yeah, the Hurry Up and Wait Syndrome.

TURAN: How do you feel about True Believer?

DOWNEY: First of all, I liked the film just because I love working with James Wood, because he’s so fucking great. You learn a lot while you’re hanging out with him, but you wonder why he is so adamant that certain things be a certain way. And then you look back and you understand.

TURAN: Aside from admiring what he does, what can you learn when you’re working with someone who’s really good?

DOWNEY: Well, we were doing a scene together, and I was right on the edge of not acting but really making something happen, you know? It’s like trying to really make something spontaneous or great happen. I was saying my lines, and he was just looking at me, kind of like, You’re getting there. You’re getting there. And then I laughed because it was like masturbating. He got this weird look and cocked his head a little bit to the side, and he just reached over and fucking cracked me right in the middle of the take. And if it hadn’t been him, or if the timing hadn’t been right, I would have said, “What the fuck are you doing?” But he’s so smart, he slapped me on the side of my face that wasn’t to the camera, and he slapped me on my neck instead of my face so a big red mark wouldn’t show up. He even thought that out—I think I’ll slap Downey today.

I trusted him enough and was willing enough to learn—it wasn’t like I needed to be slapped or anything. He was saying, Here is the point where you can’t let the door close, and he put his foot in the door by slapping me, and something great happened. I don’t know if they used it or not, but to me it was a personal breakthrough because it was him saying: That’s why you’re doing what you do—right now—and the door is closing. Don’t let it close in the future. By putting my foot in here you’ll remember—you don’t want to get slapped again. But symbolically to me, it’s like putting the flag in the ground; it’s something monumental. You got to the top of the mountain, and now you don’t have to go back down.

TURAN: Is it true that he named you Binky?

DOWNEY: That’s because he thought I was preppy. Or because he said that I wore more silk than it took to land all the troops at Normandy. He would always make fun of me because I’d come to the set in a suit at 8 a.m. just because I bought all this shit and wanted to wear it. So he thought I was foppish, and he called me Binky. Pretty soon I’d go for lunch and they’d say, “What do you want today, Binky?” It was one of those Preppy Handbook appropriate male names. But I’m just happy because it means he liked me.

TURAN: How many films have you made? 15? 16?

DOWNEY: It’s probably less because I usually count Dad’s films, too.

TURAN: Why have you made so many?

DOWNEY: I could’ve made twice as many.

TURAN: Really?

DOWNEY: Sure. Well, there might have been some scheduling problems. First I was working because I could work. I liked doing it, and someone who I respect said to me recently, “It’s important to keep working.” Now I want to be selective, because I don’t want to be known as someone who’ll do just any film or keeps making the same mistakes. Even in the course of trying to be selective you make mistakes anyway.

TURAN: Do you have anything you regret, or is that just not your personality?

DOWNEY: My personality is to regret as much as possible. [laughs] But it depends on what mood I’m in on a particular day. Because there are regrettable things about every film I’ve been in. I’ve yet to be in a film where I’ve said, “Now that’s the kind of film I want to do.” I’ll bet when Cry Freedom was over Kevin Kline said, “Well, that’s the kind of movie I want to do.” But hardly anyone saw it, and when I met him I told him it was great. And he said, “Yeah, well, now maybe some people will see it because it’s on cable.” So I just want to be happy doing whatever I’m doing. Because they’re all going to say whatever they want anyway. I’m not going to be negative, but this business is so geared to Roman-candling people. “I’m going to Roman-candle you, and then we want to skeet-shoot you because, God, you blow up so good.” Then there are the ones who are untouchable because of their talent or because they’ve been smart enough not to let themselves get fucked over. But it’s really dangerous; it’s hard to even believe anyone anymore.

My dad is one of the people who really care and who are really objective. He’ll say: “That was good. Your work was good in that. You were trying something.” Or: “That was stupid. Why did you do that?” He gets angrier about interviews or TV things that I do than about anything else. He says: “You don’t need to do it, or if you do it, why do you talk about stupid shit? Or you say so much that there’s no mystery about you.” I always call my mom and ask her, “What should I do with this and that?”

What I want to do is work with my old friends. I’m not saying that I want to work with only the people I’ve already met, but I want to work with the people I trust and can really learn from, people who want to be catalysts for each other as opposed to: O.K. Insert Actor A here. He’ll do that because he’s done that before just as well and he can do that better here now.

TURAN: When you read first scripts what are you looking for?

DOWNEY: I’m looking for anything that doesn’t seem like the same skeleton with a different crew. “Well, this one is Raising Arizona meets Something Wild. This one is like Big meets Bigger.” I just want to do something that’s different. But then you want to be in a movie that’s good and successful. Then you gotta have 9,000 rewrites and nine directors.

TURAN: There’s an old film called Hollywood Boulevard. It’s about a studio called Miracle Pictures. Their motto is “If it’s a good picture, it’s a miracle.” Given what goes on, it really is amazing if a good picture comes out of the studio system.

DOWNEY: Well, it started off as entertainment and show biz—like cheesy, cigar-smoking, high-life stuff—and now it’s turned into such big business. But I don’t think film has really been used for what it was meant to be used for. It’s such a new medium.

TURAN: Everyone knew as soon as they saw Less Than Zero that this would be the film that would establish you as an actor. Did you know that when you read the script?

DOWNEY: Yeah, but I was thinking more, This is probably going blow some minds, probably my own too. And I thought, I really want to do it right. No one likes touching those weird subjects, and I think those are the kinds of roles that I want to do, but now they don’t have to be rich kids on dope. I could do a thousand films that are easy for me to do—that’s if I don’t fall in the next year, because everyone’s about to fall.

What’s so funny is you look at all us young guys and we’re already thinking, Well, I’m going to branch out into directing, and it’s going to be this and that. Well, we’re still kids. In a way we’re locked in now, you know what I mean? It’s as if you sign a pact with the Devil. [takes on a demonic voice] “You have a big house and a black German car. Keep making movies forever.”

Everything that I’ve worked so hard for is there. Acting is the most wildly overpaid position imaginable. “How much did you make for eight weeks sitting in your trailer?” “More than the President.” It’s really silly. I want to give myself the freedom not to have to be projecting my whole life ahead. But right now the idea of dropping out of the business for five years seems like a gloomy jail sentence. It’s a business that can keep you young forever, or it can make you old before your time, and it all has to do with your perspective, what your beliefs are and how strong you can stay throughout it all.

KT: You went to high school out here. Do you ever see anybody you went to high school with?

RDJ: Well, I dropped out in the eleventh grade. But a lot of them are still friends.

I still hang out with them all the time. They say about your friends from high school that you have an inherent trust in them, especially with the paranoia that can come along with being “successful.” They liked me before. …

KT: You were somebody.

RDJ: They knew I was somebody before I did. They bring you back down to earth.

KT: Did you ever take acting lessons?

RDJ: At Santa Monica High I had this theater-arts teacher who used to be jealous of me. And I read The Twelve Rules of Theater, and that’s easy stuff, but I think I did learn, because we did Oklahoma! and Detective Story. We did The Rivals by Richard Sheridan, and I played Captain Absolute. I learned how to tap-dance and sing. I was being trained to be in a bunch of revivals in regional theaters.

KT: Did people think you had talent then?

RDJ: They probably thought I was going to go over the fence after the third period, which I inevitably was. I’d sneak back in and hang out in the theater-arts rooms. That was pretty crazy, doing Richard Sheridan, doing The Rivals. It was in the round. Ah! And my friend Ramon Estevez taught me how to tap-dance for Oklahoma! And I had sung before, so that was cool; I had been in a group doing madrigals and stuff. Sometimes I miss those times when your whole focus of the day was school, and after school you would get shin splints from tapping around. You weren’t being paid, and it was only for two nights.

KT: Baby, It’s You was your first official film.

RDJ: I think I had three weeks’ work on it. I had scenes with Rosanna [Arquette], and I talked wild shit to everyone about how I was the next Dustin Duvall. Then they cut those scenes out, and I was in only one scene, being blocked by a very eager young actress leaning across the lens. So you can see me for just a second. My friends called it Maybe It’s You. So now I don’t say I’m in a film until I’ve seen it. “I hear you’re good in Chances Are, Robert.” “I don’t know if I’m in it. I’m going to wait till it’s on cable and be double sure.”

KT: What was working with George C. Scott in Mussolini like?

RDJ: We were all in Yugoslavia. It was horrible. And you think about the guy who’s been in Patton and all those fucking amazing movies having to be who he is in the shittiest fucking possible country to shoot in. We were all unhappy there. I’m not saying that he really even liked me, but he didn’t dislike me, which is why he might have taken any interest at all in me. But there was a scene we were doing. We were shooting in Yugoslavia; it was a small crew. The director was holding his place in a fishing magazine. Nice guy, but he prefers fishing. We were shooting George’s closeup, and I started running toward these planes. Some people get mesmerized by turning blades. I almost ran right into this fucking propeller. I’ll always send Gabriel Byrne a Christmas card because he saved my life. He pushed me out of the way of this thing. And I was suddenly down on the ground and said: “Jesus Christ, it made sense to me to run through that. It seemed like my mark was on the other side of it.” And George Scott just said: “Cut! You stupid prick! Always look where you’re going! What the fuck are you doing? Goddamn it!” He was pissed off that I almost made him have to watch me die on his closeup. But it was a general concern, too. It was cool. I did it again for attention.

Another thing about George-more important than anything else-was that he kicked everybody’s ass in that country in chess. People were flying in from all over. [with strong accent] “Must be play the George C. Scott.” He was like [imitates Scot] “Check!” [laughs] That was really great to see. And he wasn’t even really paying attention when he was doing it.

KT: What was it like growing up with someone like your father?

RDJ: I really do feel blessed, and I have a feeling, seriously, that we pick our parents before we come into life. I don’t think it’s at random, and I don’t think we’re a product of our environment after a certain age. I know that he was my only move. He broke ground. He inspires you to want to go one step further. And it’s so funny now, and typical, that the business really likes suppressing any ahead-of-its-time stuff because they want to keep everything right where it is, which is big movies about guns, dicks, murder, and blowing everything up. He also liked spontaneity, I have to say. The main things were independence and spontaneity. I’m so glad that I wasn’t an Army brat or something, because I think I was meant to be in the field I’m in. And I feel happy that I’m not like any other actor. Just as I don’t think my dad is like any other director. And it’s not as if he’s tried. It’s not as if he’s sat down and said, “How am I going to be wildly original today?” He sees me doing all the stupid shit that he did when he was my age, and he’s just not going to let me get away with being an asshole. He’s more of a dad than ever. And he doesn’t miss anything. His eyes have something going on behind them. He’s still such a kid.

KT: Your father remained his own person. Is that something that you want to learn from him?

RDJ: Oh, yeah. I really do. Also, if I go into directing I could learn a lot from him. Working with him on Rented Lips was great because he always called me by my character’s name. He went out of his way to make sure that there were no concessions made to me because I was his son. Meanwhile I was playing a porno star in fishnet underwear, doing a scene with Edy Williams—I don’t know where that came from. He’d let me sing songs and do improvs. It makes me feel good that he’s proud of me. I think he’s proud that I’m not as stereotypical as I easily could have been. God, I hope he likes this interview. He’s going to be really pissed off at me if I say anything stupid. Seriously, my main concern now is that my dad will not like this.

KT: Is there anything else that you want to do or want to avoid that comes from knowing him?

RDJ: There’s a real spiritual undercurrent in his work. Putney Swope was about how no one is free from corruption, and commercialism kills everything, but creativity can prevail. Or in Greaser’s Palace God is very much alive, but He could be as real as the sunset or as silly as someone in a zoot suit on his way to Jerusalem to be an actor/singer/dancer because Agent Morris awaits him. I don’t think Dad likes talking about it that much. But I think there’s a real spiritual integrity in his work, even though a lot of it just seems off the wall.

KT: What do you think people’s biggest misconception about you is, people who just see you onscreen or read about you in magazines? What do you think they’re most likely wrong about?

RDJ: I wonder what their misconceptions are. They think they know me on the basis of what they’ve seen of me in a film. I’m sorry, but you’re not going to see me walking out of a hotel room in Palm Springs looking like I’m out of it on drugs. Or maybe it’s that I’m not deep. Why are they wasting energy trying to come up with conceptions about anyone else if they haven’t found themselves?

KT: Is there anything about being a well-known actor that you’d like to change?

RDJ: I think I’m what I’m supposed to be. I wish I didn’t get detained on the streets so often. Or what I would change-even though I think it’s something that I need to learn to deal with more directly-is people thinking that it’s their right to be able to take up your time, get insecure, and be negative in front of you. Just because these people pay six dollars to see films I’m in, does that mean that I am something they can tug around by the arm and make sign napkins or deface fuckin’ Federal currency by writing a note to their aunt on it? That is what really makes me feel like a whore sometimes. I’m reading The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell. I’m not talking about myself, but you look down through the years. You think about myths. There used to be the Greek gods. Now there’s Mel Gibson. You know what I mean? They deify people in this business and in the music business. You take Bruce Springsteen-he could be fuckin’ Jupiter. I think it’s people’s own lack of connection with themselves.

KT: When I was a sportswriter I was once seated next to Heywood Hale Brown. It was a Redskin crowd, and he said, “To the eternal question ‘Who am I?,’ ‘I am a Redskin fan’ provides a convenient answer.” Do you ever have days when you get up and just want to be quiet?

RDJ: Yeah. But I get bored easily. I don’t really spend a lot of time alone. That’s my New Year’s resolution: spend some time alone. But have you noticed how many times this phone has rung?

KT: Several.

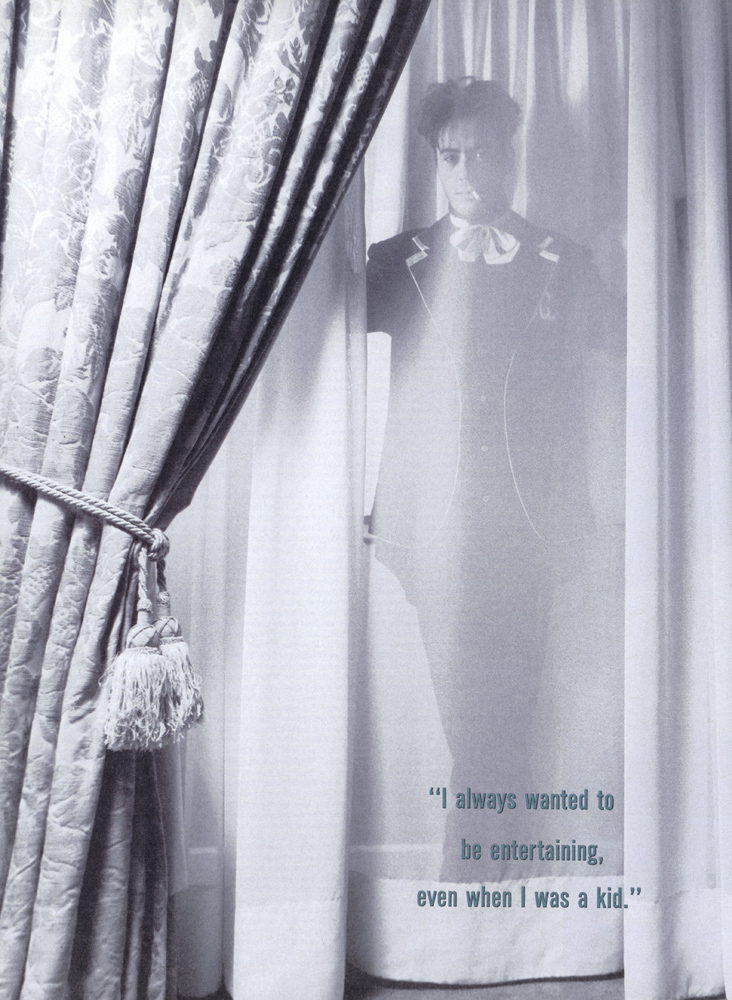

RDI: And it’s my own fault. Here’s what it is symbolically: either the phone’s ringing, or a million possibilities are calling. I usually seem to have the phone faxing to my brain. I think I was always someone who wanted to be entertaining or whatever, even when I was a kid. But now you just start to realize that it’s pretty sad. Spending time by myself doesn’t have to mean having no one else in the house but just being able to slow down and have quiet times. I play piano, and that chills me out.

KT: Are you getting to an age when you think about getting older and what you want to do?

RDJ: Yeah. You think about what you want to do with your life, and you want to do the greatest things imaginable. I guess it would be great personal satisfaction, but it is just trying to leave the world with a big middle finger, saying: Look what I did. I revolutionized the industry. Or: Look what I did. I came up with some form of sound pattern that cures AIDS, or whole cities run on my brilliant invention of the electric ice cube, or whatever. When I’m 80, when I’m thirty years older than my dad is now, I want to still have those happy, crazy Irish eyes, so that if some young kid comes and says, “Hey, you, old man,” I’ll turn around and say: “Shut up, you little fucker. I’ll tear your eyes out!” I want to be a wild, shit-talking, hearty old man. I want to be fuckin’ Popeye with a nice jacket on.

I hope not to be bitter and not to get fucked up. You think about what else you could do. I could write music; I could work with handicapped kids. But there’s something inexplicable between “Action!’ and “Cut!” which is a time that’s really so timeless. And I don’t want to explain it; I just like it sometimes. There’s been maybe a combined twenty minutes of pure feeling of creative expulsion that keeps me involved in it. And I’d probably be the most unhappy veterinarian imaginable, because I’d be looking in the papers, saying “Oh, look, another movie triumph.” By the way, isn’t it amazing how they’re going nuts over half-assed movies lately? “One of the great ones! Magnificent! Second to none!” Do you think these people are paid off?

KT: No, I don’t think so. If you never read a book and someone gave you a trash novel, you might think it was the best book ever written.

RDJ: I’m tired of complaining about it. We all know the facts. I should get off my ass and do something about it. So many of my peers have their own production companies. Don’t sit around and say: “This script sucks, that sucks. Why doesn’t this have any light in it? Why isn’t this one talking to me?” Stop believing that you can’t write, and do it. Or find somebody who can write. Change it. I think that we all have a serious responsibility. All of us young guys and older actors, actresses, grips, DPs, caterers-everyone has his responsibility to push it forward. It’s probably at its most lucrative ever, yet at its most stagnant. Maybe we’d all be happier if it were a little bit greater and we were a little less rich. [laughs] Maybe we should all be dirt poor and have the best string ever.

KT: Does it make you nervous when you don’t have anything coming up, or are you happy?

RDI: It’s like that pleasant pain you get in your feet when you’re standing on a ledge in your socks. Every actor wonders if he’ll ever work again. Well, who started that? Now they’ve got everyone believing it. Why don’t they say that as soon as you wrap on a film you have two great months? Instead you wonder if you’re going to work again.