in conversation

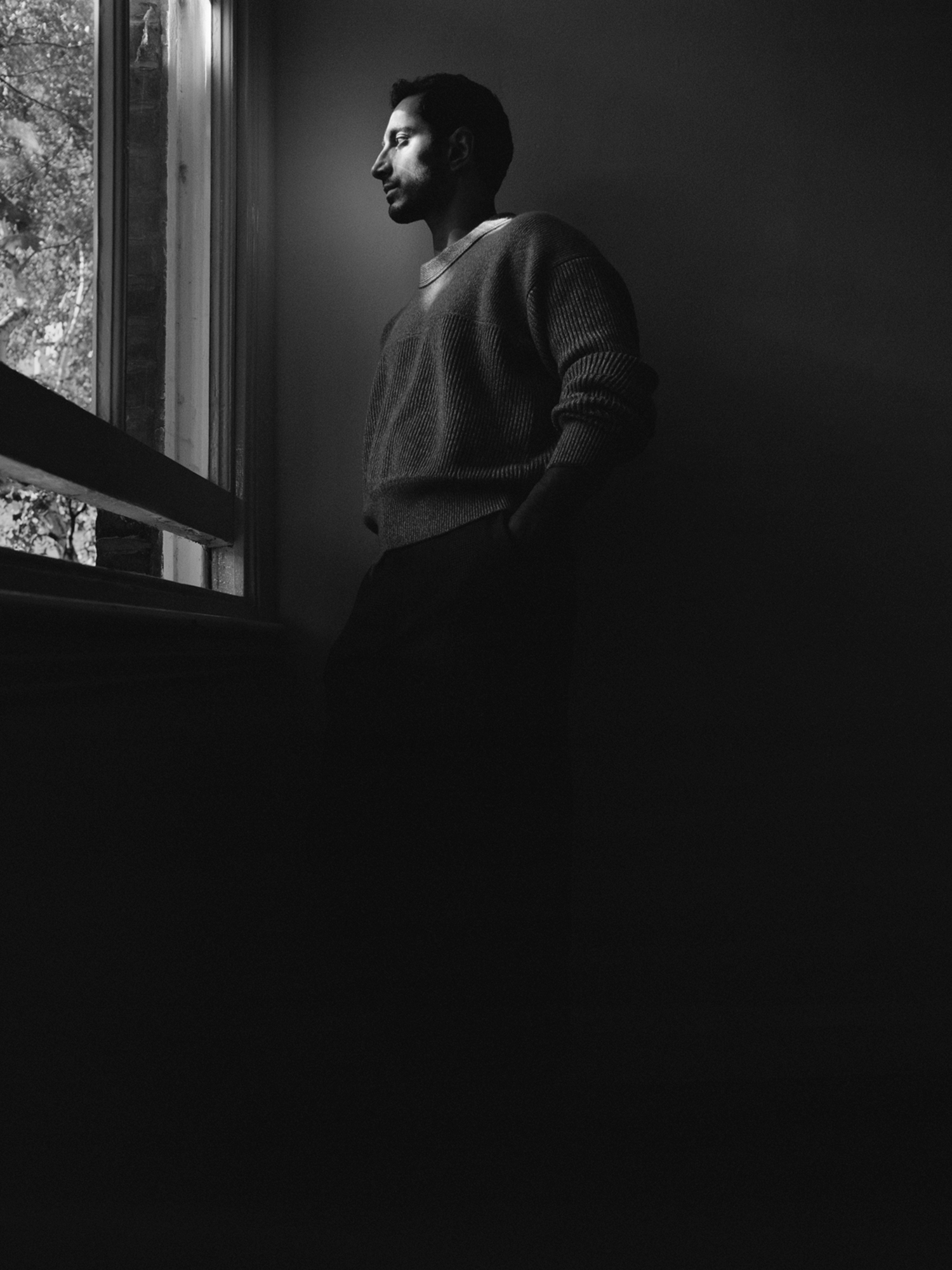

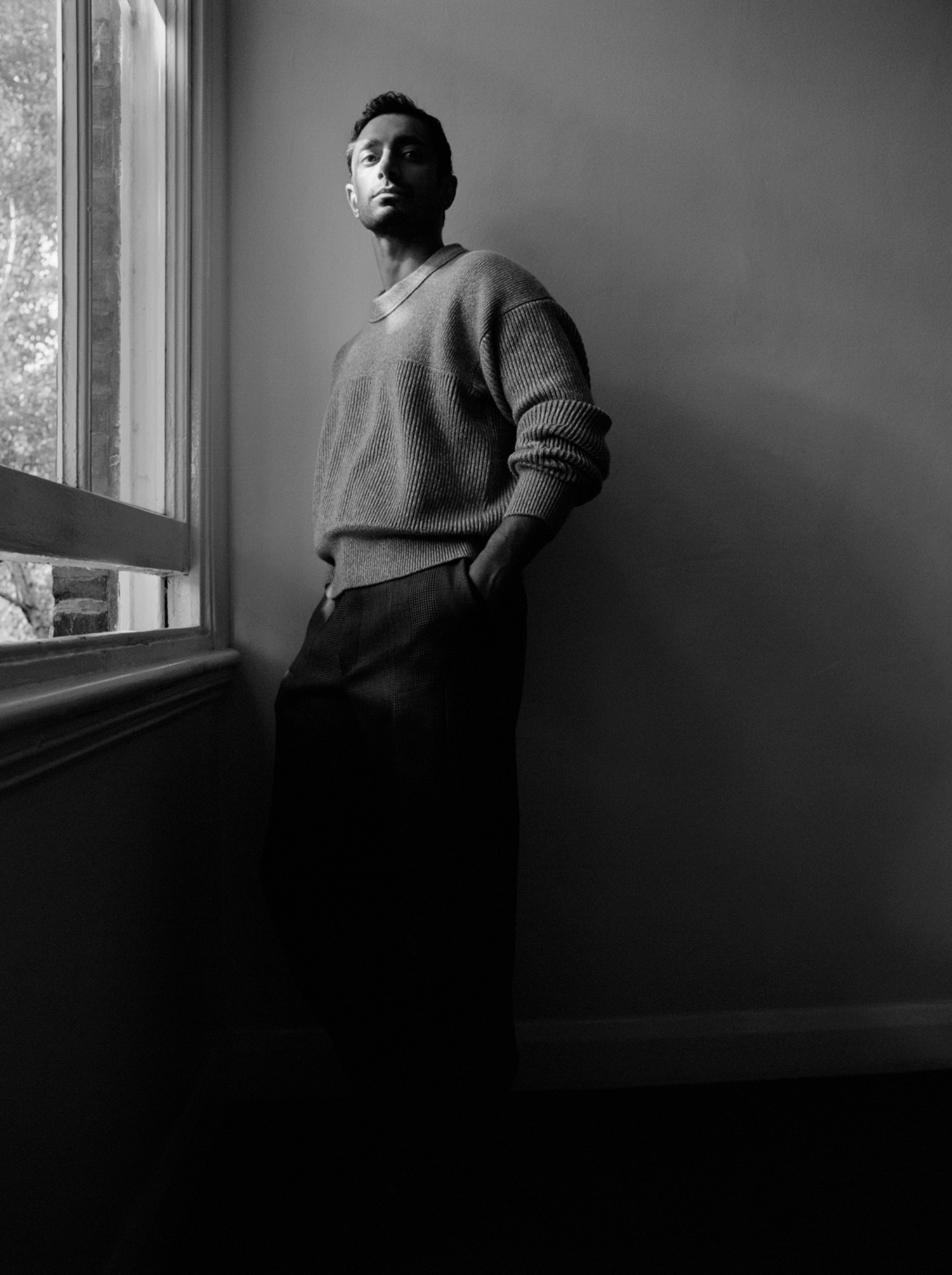

Riz Ahmed and Octavia Spencer on The Burden of Representation

At the Primetime Emmys in 2017, Riz Ahmed became both the first Muslim and the first Asian man in the ceremony’s 69-year history to bring home an award for Best Actor. Ahmed clinched the career-making accolade for playing Nasir Khan, a first-generation Pakistani-American student who finds himself at the center of a brutal murder case in the HBO miniseries The Night Of. Ahmed has long been aware of the responsibility that comes with being one of the few people representing a community of several billion in an industry that has long neglected the experiences of nonwhite storytellers. That awareness is reflected in his body of work, a stereotype-defying collection of gritty, delightful performances. From his breakout appearance as a fumbling hustler in the hardboiled thriller Nightcrawler to roles in blockbusters such as Rogue One: A Star Wars Story and Marvel’s Venom, Ahmed’s characters repeatedly complicate or transcend popular conceptions of the Muslim and Asian diasporas. But for the 37-year-old actor, musician, and activist, being among the first is not a sign of victory. It is a reminder of how far we have yet to go.

This winter, the North London–born jack-of- all-trades co-wrote, produced, and starred in the indie drama Mogul Mowgli, a darling of the 2020 festival circuit. In March, he released his debut solo album The Long Goodbye, a politically incisive, critically acclaimed rap record that chronicles the art- ist’s own Brexit-fueled breakup with Britain. And this November, he will star in Sound of Metal, an immersive drama that follows a heavy-metal drummer who spirals into addiction when he begins to lose his hearing. Though Ahmed underwent months of musical and American Sign Language training to prepare for the role, the biggest challenge came from tapping into his character’s rage and grief. Rejecting that feeling, he tells his friend and future costar Octavia Spencer, is something he understands all too well. —MARA VEITCH

———

RIZ AHMED: Hey, I’m looking forward to seeing you in a few weeks.

OCTAVIA SPENCER: I’m really excited. I have to tell you, you pick really wonderful projects and interesting characters. Performance-wise, I think Ruben [Ahmed’s character in Sound of Metal] might be your best work yet.

AHMED: That means the absolute world coming from you. I’m just upset that when we start filming Invasion, we’re not really going to have any days on set together.

SPENCER: It’s a shame.

AHMED: It is, because I love to learn from people who have real experience and talent that I admire.

SPENCER: Sweetie, you don’t need anybody teaching you anything.

AHMED: You mentioned choosing characters. I feel like every day I watch another film and I’m like, “What! Octavia’s in there!” The other day, I was watching Being John Malkovich and there you were.

SPENCER: Oh yeah. Those were the days when the role chose you, and you were excited just to get it. That was one of my favorite projects.

AHMED: What do you feel like that period of your career gave you? You say you weren’t choosing the roles, but what were your goals when you took on a role, and how has that changed now.

SPENCER: I see it as the education that got me to where I am now. Like you, I love watching other actors act, and I love to take direction. I think it gives me a stronger connection and a better short-hand when working with people whose practice I respect. I used to come in on days that I wasn’t scheduled, just so I could watch the other actors.

AHMED: Does that mean you’re an actor who watches the monitor a lot?

SPENCER: Oh no, I hate watching the monitor because it makes me realize it’s all pretend. Even though I’m a producer now, I don’t like doing that. But I want to hear you answer this question.

AHMED: Every time I take on a role, it’s like learning a new language. I have to remind myself how the whole system works. My relationship to watching my own playback changes from job to job. On bigger and more technical projects, it helps me to work out how all the moving parts fit together, but with Sound of Metal it was something we certainly didn’t have time for, which was kind of a blessing. It forced me to take off those training wheels, and work without that stabilization. To let the self fall over publicly. That’s often where the magic comes from.

SPENCER: Every character has a set of skills, and if you, the actor, don’t have them already, you have to do your research. Did it scare you to play a musician who loses the sense that makes him who he is?

AHMED: Absolutely. I was frightened on both the skill-learning and the emotional resonance levels. That’s why I felt like I had to do it. I had been working on bigger, more logistical projects over the previous few years, and I wanted to do something that would overwhelm me and unleash me. Yes, I’m a rapper, but I cannot play the drums, nor did I know any American Sign Language at that point. So I spent every day for several months learning how to play the drums, learning ASL, and going to that place of addiction and loss. It really struck a chord for me, because there was a period in my life when, due to my circumstances, I was unsure if I would be able to continue doing what I love. In a way, I feel like Sound of Metal is a COVID movie, because you’ve got this workaholic who is suddenly stranded in purgatory due to a health crisis, and he has to sit with himself. For many years, my addiction was my work, and I think this virus has helped many of us realize that our careers are a Band-Aid or a distraction. It’s difficult to sit with that silence.

SPENCER: Absolutely. That’s why I’m guided by roles that resonate with me personally. If I take on projects based on the social impact that I think they’ll have and it backfires, I lose my sense of self.

AHMED: That’s something I think about a lot: the duty, or burden, or desire to represent. I would love the freedom to just follow my curiosity without having to analyze what I choose to give a platform to. At the same time, it’s such a gift to be animated by a sense of mission beyond your own creative interests. How do you navigate that? Do you ever find yourself going, “I should do this job, but I don’t want to,” or, “I want to do this, but I shouldn’t”?

SPENCER: I’m an artist and a storyteller first, so I don’t make choices based on causes alone. If a project that feeds my creative needs also happens to entertain, enlighten, and allow for a little escapism, great. But I get asked to do a lot of things for a lot of causes, and if I lay my name to everything, then it has no value for those things that I truly need it for.

AHMED: This idea of boundaries is something that a lot of artists coming up now can really learn from. If we’re constantly rushing to represent, it disconnects us from our sense of self. It’s something I had to navigate when I was starting out 15 years ago, as one of the only members of the Muslim diaspora appearing in TV dramas and releasing music. It created a tremendous amount of support, but also a lot of pressure and very high expectations. I was acutely aware that any role I inhabited risked becoming an archetype— it’s not like you were going to see ten other Muslim dudes in films that year. But it’s quite liberating to know that you can’t please everyone. At this point in my career, I think a lot less about represent- ing and more about how to be present myself. I think that is what freedom looks like.

SPENCER: That’s exactly it. I’m in a Friday night group where we watch all the Best Pictures from the Academy Awards and dress up as one of the characters to discuss the movies. Some of them have held up, but some of them haven’t. I hope that, when I look back 20 years from now, I’ll feel that I made work that was progressive and still lives up to my ideals.

AHMED: So that’s how you’ve been spending lockdown: a Friday night fancy-dress film club! Send me an invite, I’m there. [Laughs] Thinking about legacy and impact is so tempting and so toxic, isn’t it? It’s a really easy way to paralyze your- self. Both Sound of Metal and Mogul Mowgli, another personal project I put together, deal with artists who are prevented from having a lasting legacy. In both films, my character realizes that one of the best ways to have an impact is to make space for others. I’m also a producer now, too, so I’d love to know what drove you to move into that space. Was it a sense of frustration that certain stories weren’t being told, or did it happen organically?

SPENCER: I always wanted to produce, but acting just happened first. I’m dyslexic, so every morning the first thing I have to do is wake up my brain with puzzles and brain teasers. I see producers as the people who fit all the pieces together. I always felt that if I relied on other people to get me work, then I’d be out of work rather quickly, because, like you said, people only see you in these archetypal roles. By producing, I get to hold the reins a bit tighter while providing opportunities for other marginalized storytellers. Did you have a similar reason?

AHMED: Very similar. My curiosity and appetite fall outside the boundaries that are placed around someone like me. I started working around those constraints very early on, just contacting people and saying, “Hey, I want to work with you.” I didn’t realize that what I was doing was producing, and eventually people were like, “You can get paid for that.” So, it started off as that personal hunger, but I think the reason I decided to formalize it into a company is that I realized how much amazing talent there is in communities of color in the U.K. and the U.S.

SPENCER: Exactly.

AHMED: We talk about the scarcity mentality—that there’s only room for one or two of us. But when you stretch the culture, you create more space for different kinds of people to tell stories. If there were more of us doing this, imagine what that freedom would feel like.

———

Grooming: Tara Hickman using Tom Ford Beauty

Photography Assistant: Sam Binymin

Fashion Assistant: Guy Miller