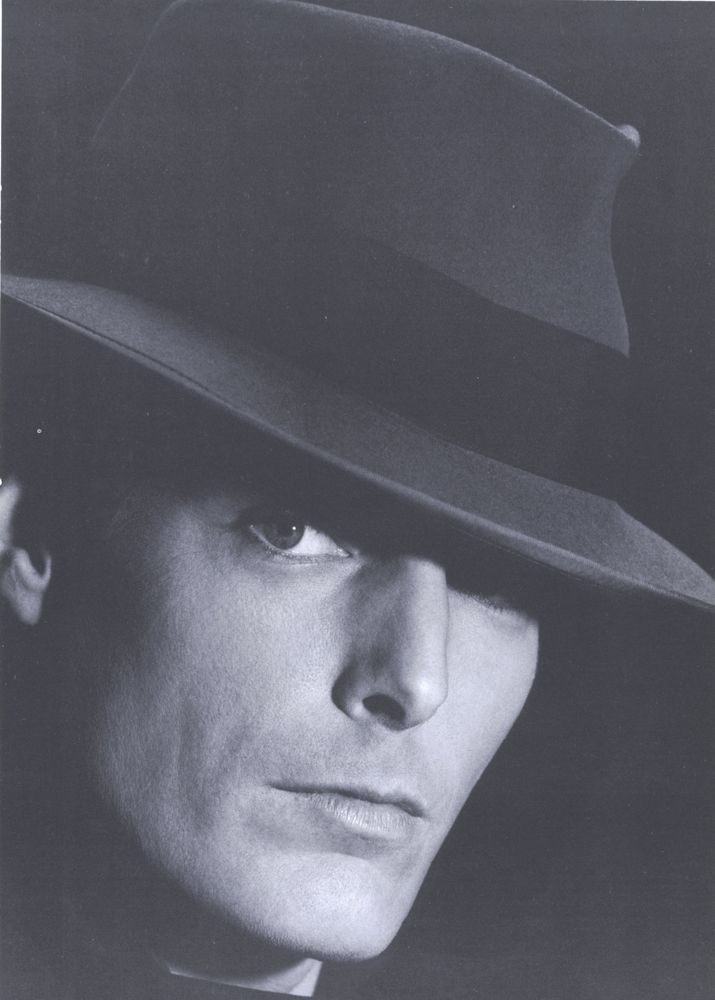

New Again: Remembering Christopher Reeve

In New Again, we highlight a piece from Interview’s past that resonates with the present.

“The bigger the canvas, the better I do. I’m not so good at understated, kitchen-sink kinds of parts,” Christopher Reeve told Interview in 1986. Born on September 25, 1952, Reeve was an American actor, film director, producer, screenwriter, author, pilot, and superhero. Raised by his father, Franklin Reeve, who was an activist and intellectual, and his mother, journalist Barbara Pitney, the significance of political theater was forced upon Christopher. Franklin pushed his son in the direction of an atypical acting career. In 1978, however, Christopher decided to go his own way and starred in Richard Donner’s Superman film. Handsome and sharp, Reeve strived for the recognition and appreciation of his classical ability as an actor. He accepted the momentous role of Superman because he saw it as “the closest expression to something of mythical dimension.”

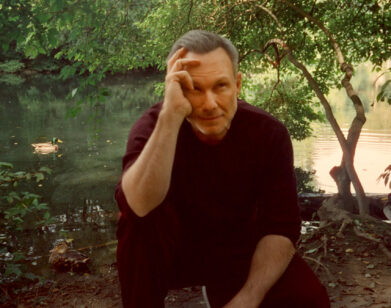

In 1995, Reeve fell from his horse during a competition and permanently injured his spine. He founded the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation and the Reeve Irvine Research Center to help find a cure for spinal cord injuries and paralysis.

Eight years ago today, we lost Reeve due to cardiac arrest at the young age of 52. In memory of the great actor and activist, we’ve reprinted our 1986 interview with Reeve. Here, Reeve explains his father’s influence, the significance of playing an idolized superhero, and the decline of film.

Leading Men: Man and Superman

by Gregory Speck

Having played the Man of Steel to worldwide acclaim in three major films, Christopher Reeve has been enduring the burden of that screen persona in his private life for seven years, nearly losing his own identity underneath the weight of the hero whom he in so many ways resembles. His fight against Superman has been a source of frustration, but Reeve’s fans will be happy to learn that he has reemerged as the real Chris Reeve and is prepared to resume his career with a rediscovered openness. In fact, a sequel in his celebrated defense of “Truth, Justice, and the American Way” may even be in the cards.

In New York for the Broadway run of The Marriage of Figaro, Reeve met with me at his Upper West Side triplex. The conversation that followed should go a long way toward dispelling the occasionally-voiced opinion that this actor is simply a physical phenomenon.

GREGORY SPECK: How do you see yourself?

CHRISTOPHER REEVE: That goes back to my upbringing. My father is an intellectual and physical man, which is a rather unusual combination. He’s great. As he brought up me and my brothers and sisters, he ingrained in us that your appearance is not your responsibility, other than that you should not be a slob. You should take some responsibility for the way you present yourself. But you should not be hung up on your looks, whether you are ugly or handsome, because it isn’t an achievement.

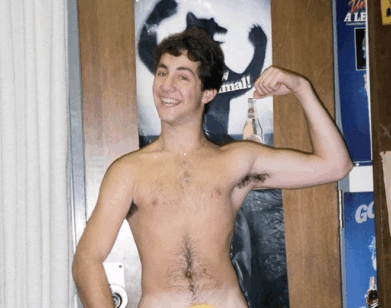

It never occurred to me that I was a leading man until I was 19 years old. I had been acting since I was 10, so that’s nine years and 30 or 40 plays, in school and summer stock, professional theater, too. I did my first apprenticeship when I was 15, then joined the union when I was 17. I worked every summer in high school and college. Actually, Ellis Rabb had to make little speech to me one day, when I was appearing in the San Diego Shakespeare Festival, doing three parts. One of them was Richard III’s older brother, Edward IV. Well, I was in a wig and full makeup and just acting my little ass off having a great time, and really doing a pretty good job of it. At the same time, I was playing Fenton, a sort of young romantic type in The Merry Wives of Windsor who comes out to tell the audience what is already known. So, Ellis came up and said to me, “Your Edward is very commendable, but your Fenton is a mess, and I simply don’t understand why you can’t come on and be six feet tall, and present yourself and be handsome and let us admire you.” So I said, “Oh come on, what are you talking about?” He was very firm, though, and got me to accept the idea, which up to that point had been completely alien to me, that it is okay to be your physical type, the truth about who you are. Before that I had always thought that acting was neutral ground, that your appearance didn’t matter, that you didn’t need to use your background or the truth about yourself in a role because you were playing something else. Then I really learned the lesson, 10 years ago, from Katharine Hepburn in A Matter of Gravity. She showed me that acting is not a way to hide, but to reveal the truth about yourself—that you aren’t the character, and you never will be. The character is a piece of fiction. You are yourself, however, and that makes you interesting, because you’re alive and you’re a human being. And if you can channel the truth of your own experience onto the stage, that’s what the audience wants to see. That point of view opened up a completely new world for me. That’s what she does. She uses her knowledge, her experience, her intuition, her intelligence, her life—all of that goes into the character she’s playing in such a way that you can’t tell where she leaves off and the character begins. Like all great stars, of course, she has a completely original personality, which helps to put things over to the public. Like Spencer Tracy or Gary Cooper, she is a conduit of truth, both about what the playwright wants to communicate and about herself. That’s what it’s about, that star quality. That’s what magnetism means; that someone is available to you, to allow the truth to come out. When I began to learn that lesson, I began to act better.

SPECK: Do you have the same star quality?

REEVE: Maybe one way I am original today is that at heart I really am a classical actor. I haven’t had my chance yet in the commercial world to show that. Movies aren’t really made about classical people so much any more.

SPECK: They don’t write scripts the way they used to, either.

REEVE: No, they don’t need to. The youth market demands something else. You know, in retrospect I’d say I probably ended up playing Superman because that’s the closest opportunity I’ve had to playing a classical role on film, the closest expression to something of mythical dimension. If you want to be serious about it, there are pseudo-classical elements to the character of Superman. There is a comedic and romantic strain in me that has not yet fully revealed itself, and I think I would do better with bigger characters. The bigger the canvas, the better I do. I’m not so good at understated, kitchen-sink kinds of parts. The people who populate the stage and screen today are very ordinary. In the second half of the 20th century, people are becoming more limited: Vocabularies are smaller, thoughts are smaller, aspirations are smaller, everything is very scaled down. Today everyone is typecast.

SPECK: When you say that writing and acting have been reduced to a level of banality today, is that the result of method acting or an increase in illiteracy or what?

REEVE: I don’t think actors are to blame for poor writing. The culture changes first, and the theater follows it. In the case of the movies, it’s the same thing. I’d say that the movies are made because the people making them are in the business of giving people what they want to see.

SPECK: Do you want to see most of the movies that are released?

REEVE: No, I don’t at all. Where are the romantic comedies that they used to make and no longer do? Where are the movies that depend upon wit, sophistication, style? Well, they don’t make that kind of film any longer, because first, you can see the real thing on the late show in revival, and second, the kinds of characters in these old movies are no longer identifiable in our culture.

SPECK: I thought you were the classic, all-American boy.

REEVE: Not by a long shot. I’m from another time. Definitely not from right now.

SPECK: You mentioned that your background had a major effect on the development of Chris Reeve.

REEVE: I was born in New York City and grew up in Princeton, New Jersey. Having that college-town atmosphere with a live repertory company available was a real gift. I found myself gravitating toward the theater from about the age of nine. I guess it was the environment that got me started. I was invited to play a small part in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Yeomen of the Guard. I was a soprano at the time. This was a very exciting departure from the routine, because I got to skip school and make up the homework. I guess all kids are looking for some way to get singled out of the crowd, some way in which to distinguish themselves, and this was mine. I got a lot of recognition for it early on. I didn’t know what I was doing, which was probably a good thing, because it came very naturally to me. Then, when I was 14, I went to a theater workshop in Lawrenceville for the summer. I remember a director I worked under named Milton Lyon. I had just been in a production of Finian’s Rainbow, which he directed. He said to me, “You better know what you want, because you might get it. I think you might be the one in 10,000 who really has the potential to go a long way, long way.” That encouraged me; handed to me at age 14 it made a lasting impression. I have had no reversals since then. I later found out that my father had always wanted to be an actor. But he became a writer, critic, and translator instead. I think it was a way of my thumbing my nose at the intellectual establishment I was supposed to join. It was a way of saying, “I’m going to try this on my own and see where I get.”

SPECK: Which leads to your phenomenal success in Superman…

REEVE: It was an oddball, weird, unusual thing for me to do. But it led to my dropping a lot of snobbishness about culture, the actor’s responsibility and my own ideals, because I began to see that it could turn around people’s expectations. It was a real break from family pressure, too. When I first began acting, I assumed an intellectual responsibility attached to my profession, which I had accepted for a long time. My father taught me that an actor had to have a social and political conscience, and that the work that he does has to reflect from that. From my father’s pint of view, I should have been going toward Peter Brook or Grotowski or The Group Theater. He seemed to expect me to be down in a little loft in SoHo doing a production of The Birds or Hail Scrawdyke! You know, something off-the-wall and giving society the finger, because this is his political perspective. I don’t blame him at all, because he was wishing the best for me.

Anyway, I got out of college, worked a couple of summers, went to Juilliard, and got to play with Katharine Hepburn. The year after that, though, is when I made a complete 180-degree about-face. The problem was that I was not comfortable with this intellectual responsibility that I was supposed to be carrying, so I dropped it by playing Superman. I screen-tested in London, after turning down the chance a couple of times, got the part and came back to New York. At the time I wasp laying opposite Bill Hurt in My Life at Circle Rep. So, I took my father out to dinner and he said, “So, what are you doing now?” And I said, “Well, it looks like I’m going to be playing Superman.” And he looked at me and said, “Oh, that’s good. Who’s going to play Ann?” I suddenly realized that he thought I was going to do a Man and Superman, that I would be playing Jack Tanner. “No,” I said, “the Superman I’m going to play has a girlfriend named Lois.” And he said, “You don’t mean…?” That dinner was a real breakthrough in my life. People may never understand this—and perhaps I should give up caring whether they do or not—but the idea of me playing Superman is so far away from what I was brought up to aspire to.

SPECK: From what you’ve said, I get the impression that you equate left-wing politics with intellectual integrity.

REEVE: I don’t necessarily, but my father probably does. This isn’t an interview about my father, but he’s a person who had a difficult time fitting into his own background. He came from society and money in Morristown, New Jersey, and he reacted against all that privilege by cutting himself off and going the other way. At one point he was teaching night school at Columbia and unloading banana boats on the Hoboken waterfront by day. He’s never made a dime in his life. He’s always lived at subsistence level, because the place he had to be was on the outside looking in. The kind of theater he’s interested in is political, activist theater. That’s where his ideas about me came from. I was pushed, pulled, stuffed with a shoehorn, moved in the direction of a kind of avant-garde or at least outcast theater, theater of revolt. And I said, “Now wait a minute. That is not me. I’m not that intellectual. I have no bones to pick and no fight with society. And I’m willing to be and interested in being in the mainstream of society.” I finally realized that I didn’t want to be freezing with the rats down in some SoHo loft. I wanted to be in the middle of where all the action was. If I’m performing, I want to be on stage in a Broadway theater or upfront in a movie. The thing that bothers me about the intellectual stance, which says, “Life isn’t fair, and I’m suffering,” is that most of the suffering is self-imposed exile. I think that the “intellectual,” with his self-imposed suffering, is particularly ungraceful and unnecessary, and certainly not for me. So with Superman I went mainstream, took control of my life, changed it, and moved off in my own direction. I’ve been taking responsibility for myself ever since. But the public perception is that I was born on the beach in Malibu, because the part works very well for me. This caused a period of a couple of years for me in which I completely miscalculated the camp side of it. The camp side of it is that Superman as a character is a kind of goofy idea. It’s kind of a relief to think of him like that—but he’s a relief from life’s problems. There are, of course, a lot of attendant jokes that go with him, and therefore with the person who plays him. I see on people’s faces that they don’t quite know how to react to me.

SPECK: How about your future political career?

REEVE: It’s been suggested to me a number of times. There’s still a lot I want to do in film and theater, though. There are many chances I haven’t taken yet, and I think that’s going to make up the next 10 years. If I were pushing for a political career, I should be spending those years building a political record. If I wanted a Senate race at age 45, I should spend 33 to 45 building up a record on the issues, building up connections with people who could get me propelled. I already have the spotlight as an actor. If I show up at a press conference, the cameras will be there, which is unfair for “Joe Bloggs” who has to spend every nickel to get on the radio. I’d have to do one or the other, either start preparing now for a political career in my forties, or say, “No, I’m really not finished with acting yet.” Right now I have my acting goals clearly defined, and I want to spend my next 10 years doing that.

Right after Superman opened it was difficult for me to accept the hero worship that came at me. And I immediately made choices of material that, in a way, gave everybody the finger. My actions were meant to tell the public, “Don’t look up to me. Don’t think of me as a hero.” For example, one of my immediate choices was to play a screwed-up homosexual playwright in Deathtrap. As an acting chance, it offered Michael Caine, Sidney Lumet, screenplay by Jay Allen—a really nice pedigree. And yet, the character I played was one the audience couldn’t possibly like or identify with. And then I played a homosexual again on Broadway in Fifth of July—this time a veteran with no legs. It was difficult for people who identified me with Superman to come to the theater and see me sitting on the stage, and in the first scene my boyfriend comes in and kisses me on the lips. The audiences used to gasp. They couldn’t deal with it. But they stayed through the course of the play, and its humanity and the emotion got to them, and they came backstage afterward totally blown away. It was almost necessary for me at the time to play characters who were gay, crippled, psychotic, neurotic, killers, whatever. It was almost a pompous, self-important way of telling the public, “Screw you, I’ll tell you who I am, so you don’t tell me.” That is what was going on in my head at the time. I have to admit that I was a particularly ungraceful and unsympathetic person at the time.

SPECK: You didn’t carry your success with honor?

REEVE: That’s it. So now it’s eight years down the line, a lot of water under the bridge and I’m now at a point where I am not fighting with anybody. I don’t have to prove anything to anyone. As a result, I am ready to take up again the characters who are closer to what I really am. And now we come full circle. I’m closer to using more of my own personality and getting back to the kind of acting of a Hepburn or a Cooper or a Cary Grant. Those people could say, “Yes, I can use myself without same as a I perform.” And this is the 10-year plan, though I hate to sound like an accountant.

THIS INTERVIEW INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE MARCH 1986 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again, click here.