The Fabulous Punk Rock Girls

“Some people think little girls should be seen and not heard. Well, I think, ‘Oh, bondage! Up yours!'” cried the late, great punk queen, Poly Styrene on her band X-Ray Spex’s classic track, “Oh, Bondage. Up Yours.” The song reflects the sacred attitude of punk: you don’t have to be what they want you to be. The identities forged through such punk rebellion make up the subjects of Punk Rock Girls, an 11-film series starting tonight at BAMcinématek in Brooklyn.

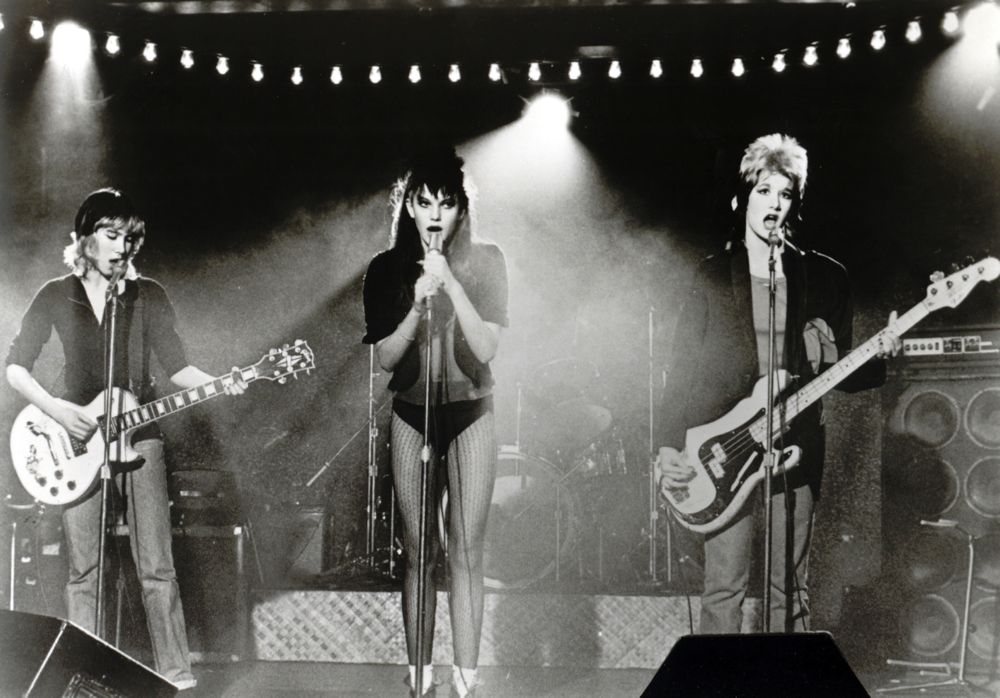

The series kicks off with a sneak preview of Lukas Moodysson’s (Show Me Love 1998, Lilya 4-Ever, 2002) We Are the Best!(2014) about three young girls who start a punk band in Stockholm. Other highlights include cult classics normally reserved for midnight screenings such as Lou Adler’s Ladies and Gentlemen, The Fabulous Stains (1982); Derek Jarman’s Jubilee (1978), featuring cameos by Siouxsie Sioux, Ari Up of The Slits, and Adam Ant, with a score by Brian Eno; and the punk melodrama about the rise and ruin of singer, Hazel O’Connor, Brian Gibson’s Breaking Glass (1980).

On the eve of the series’ opening, we caught up with curators, Nellie Killian and Gabriele Caroti to talk about their experiences of punk rock and their favorite films.

RYANN DONNELLY: How did the series come about?

GABRIELE CAROTI: I saw We Are the Best! at the Toronto International Film Festival last September, and fell in love with it. We found out that Magnolia Pictures picked it up, and have been in conversations with them since last fall.

NELLIE KILLIAN: We started running the idea of a series on women in punk off other people we knew who liked these kinds of movies, and it was one of these ideas where, as soon as you started talking about it with any sort of “cult” genre appreciator, everyone has their favorite that they felt needed to be in the series for it to be complete—like, Startstruck (1982). So it became this really fun collaborative process where we kept growing the series.

DONNELLY: What were your first experiences with punk?

CAROTI: I remember my first experience vividly. I had heard about punk music, and I was listening to a lot of New Wave– The Cure and The Smiths and stuff. A friend had a cassette of The Clash’s Give ‘Em Enough Rope; it was one of those Columbia cassettes with red on the spine. I hadn’t heard the other Clash records at the time, and I just thought it sounded like rock ‘n’ roll. Then I was listening to this radio station—I don’t know if it exists anymore—WDRE out of Long Island; it was pre-alternative radio. There was a DJ named Malibu Sue, and one night she played Anarchy in the U.K. I had never heard anything like it before. I thought it was the most amazing thing I’d ever heard as an eighth grader.

KILLIAN: I have a very vivid memory of my first punk film experience. As a middle-schooler I loved The Cure, I loved The Smiths; I was really into Dead Kennedys. But, I remember I was maybe a sophomore in high school in San Francisco, and I wandered into this alternative space in the Mission District called Artists Television Access. They were doing a program of Queercore music video. I had no idea what it was, and just sat down, and I guess it did everything. It made me uncomfortable, but it was also this very welcoming audience of experimental film aficionados. It was bands I’d never heard of, like Pansy Division, and it was a really fun show. There were these aesthetics of transgression that I was completely unfamiliar with that definitely blew my mind

DONNELLY: Do you think people relate to punk films differently than punk music?

KILLIAN: Most of the films we’re showing—as much as they’re beloved by people who love punk, they’re also part of this long tradition of alternative cinema and films that focus on sub-cultures. A film like Out of the Blue (1980) is really reflective of independent film of the 1970s—that sort of culture and how it manifested in the 1980s

DONNELLY: With so many films in the series, would you say women find greater ownership of punk through film rather than music?

KILLIAN: I think that in every one of these films there is a sense that the woman in the film are marginalized within the larger punk community, or they’re having to fight for their place in it. I think what’s interesting is that frequently, when you see movies where there’s an alternative culture that’s supposed to be more welcoming, issues of inclusivity get swept under the table. But for all these films, its really front and center that the way women enter the social circle is kind of fraught.

CAROTI: For all its criticism of 1970s disco and arena rock, punk was quite macho and masculine, and sometimes misogynistic. But, to counter that, there were bands like The Slits, The Raincoats, The Rezzilos, and Siouxsie and the Banshees, of course.

KILLIAN: A lot of these films do reflect women trying to make space in these male-dominated art movements. They’re really inspirational in that regard.

DONNELLY: Do you see the influence of these films in any contemporary work?

KILLIAN: I think Derek Jarman is hugely influential on this generation of artists. They did a whole season of his work at the British Film Institute this year. I think a lot of the ways these films combine politics, class concerns, and art is pretty timeless. They all stand up.

CAROTI: I’m sure a film like Todd Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine (1998) is taking a page from some of these films, or directors like Jarman.

DONNELLY: Can you pick your favorite among the 11 films you’re screening?

KILLIAN: I would say Out of the Blue is a really incredible movie. A must-see. It has a really dark edge. I also think Josie and the Pussycats (2001) is a really smart satire, and a fun movie. I’m happy we were able to put it on the list.

CAROTI: I like Ladies and Gentlemen, The Fabulous Stains. It has all the classic Punk concerns: selling out, not selling. There are members of the Clash and Sex Pistols in it, and they fight about reggae music. Diane Lane and Laura Dern are in it, and they’re fantastic.

“PUNK ROCK GIRLS” STARTS TONIGHT AT BAMCINEMATEK IN BROOKLYN. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT THEIR WEBSITE.