Phillip Youmans and Benh Zeitlin on Filmmaking, Curiosity, and New Orleans

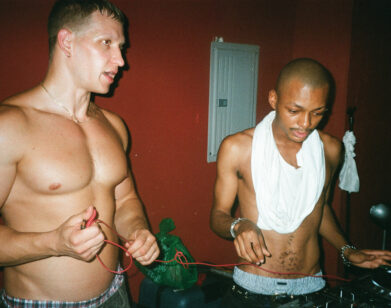

Phillip Youmans. Photo courtesy of Denizen Pictures/ARRAY.

Phillip Youmans is having his breakout moment. While he was still a film student at NYU’s prestigious Tisch School of the Arts, he scraped together funding for his feature film debut, Burning Cane, a raw and lyrical portrait of the effects of addiction on a religious community in Louisiana. The film, due to Youmans’ standout direction and screenwriting, and an electrifying performance from The Wire‘s Wendell Pierce, led him to become the youngest director to screen a film at the Tribeca Film Festival, and the first black director to win the festival’s top prize, the Founders Award. On top of all that, the film was picked up for distribution by Array, the company founded by Ava DuVernay. Burning Cane, which is streaming now on Netflix, has been met with widespread acclaim and received two Independent Spirit Award nominations, for Best Supporting Male, and the John Cassavetes Award, presented to a film with a budget of $500,000 or less. Youmans, now twenty years old, sat down with his mentor, and the film’s producer, Beasts of the Southern Wild director Benh Zeitlin, after Zeitlin’s new film Wendy made its premiere at Sundance. The two talked about what led them to make films, family, and their shared love of New Orleans.

__ __ __

PHILLIP YOUMANS: Tell me about how everything went [at the Wendy premiere], man.

BENH ZEITLIN: It’s a great weight lifted. It’s done. We had all the kids on stage. They hijacked the whole Q&A and turned it into a comedy routine.

YOUMANS: What do you think was your favorite part of making Wendy?

ZEITLIN: The most memorable moments for me I think were when the kids revealed themselves. Meeting the kids and realizing they were my characters, especially probably Yashua, who plays Peter. When I got to know him, before I really did an audition with him. He was so perfect for the character, the way that he plays, and just the way that he is. I was like, ‘There’s no chance this kid can act. He’s five years old. This would be the dream. Maybe I’m going to hang out with him to help me write this character, but there’s no way this kid could actually act.” Then we did the first acting game and when he dropped into character and nailed the scene, improving, it was about me trying to chop down his tree, that was the most… I don’t know, I’ll never forget that. I just couldn’t believe it was happening, you know?

YOUMANS: That’s great. I remember a while back, you were telling me about what your parents did. Your parents, were they antique travelers or something, they were traveled with art in some way.

ZEITLIN: No, man. Like, no one knows. My whole life, I just tell people what my parents did, and they’d be like, “What’s that? Are they teachers?” They run a nonprofit in New York that basically does all kinds of preservation, preserving sort of cultural spaces for communities and bringing artists into schools and putting on festivals about poetry, or street art. Things like that.

YOUMANS: In what way do you feel like your parents and their life has affected you as a storyteller? There’s so much about your style that’s so kind of otherworldly and ethereal, ‘magical realism’ is something that people often use to describe it.

ZEITLIN: All the time. I always wanted to not grow up to be like them when I was a kid, and now I’m just right in the wheelhouse. Our whole childhood was just filled with eccentric characters all the time. We went to birthday parties at the Coney Island Freak Show when we were five years old and got to know everybody doing those shows. We would be at Chinese operas, we would be at Gospel concerts, all these really different cultures. My parents have this incredible love for eccentric storytelling, and that certainly all finds its way into my films in huge ways. It was such a totally impractical career, they were constantly just writing grants, trying to get things funded. There was never a thought in my house that money was a reasonable motivation for doing anything. I think that that certainly gave me a lot of the courage to take huge chances, just setting out to make films. The way I make them is obviously really risky a lot of the time and not practical. How about you, man? When I first saw your film, I was just like, ‘Where did this come from?’ The themes are themes that someone at your age wouldn’t be able to talk about. I’m curious what your childhood was like. When you started thinking about working in film, being a filmmaker, being an artist in any kind of way, and how that was informed or not informed by your parents.

YOUMANS: It’s so interesting. My mom always wanted to be a screenwriter.

ZEITLIN: Really?

YOUMANS: She told her mother that, but then her mother always told her that she had to get a real job. My mom, I think, with her mother telling her that, made sure that she didn’t replicate that sort of sentiment with my sister and I. My sister’s had different interests. She’s an accounting major, she loves numbers, I do not, and it’s interesting how we’ve diverted in that way. I think there’s so much about my relationship with my family that I see in my work, even outside of my mother but of course incorporating my mother. It’s almost pointless to try to separate ourselves from our writing. It already happened, you know? Our writing is infused with us, no matter what.

So much of Burning Cane was inspired by stories that my mother told me, her growing up in Lowcountry, South Carolina. One of the first stories that she ever told me was about was the question of, a community being accountable. And this story about this pastor in Lowcountry, South Carolina, that beat his wife with a two-by-four and everyone in the church knew about it but no one said anything. To me, that was always such a… I don’t know, such a disheartening story. It definitely was in truth, a big inspiration for Reverend Tillman’s character (played by Wendell Pierce.) Preaching one thing and living another. I feel like my relationship with my mom has just developed my intention to humanize everything that I’m talking about, no matter if I agree with it or objectively disagree with it. Because I can understand why the individuals in my family are Christian, are religious, even though I personally don’t align with those beliefs, understanding why they need that emotional refuge, understanding why that’s important to them is important. If you come to any character—regardless if you agree with them or not—with any judgment, then you’re demonizing them.

ZEITLIN: Yeah. Your mom is awesome.

YOUMANS: She said you went to the Pelicans game.

ZEITLIN: Yeah, she got me tickets. It was great.

YOUMANS: She loves you, man.

ZEITLIN: Where do you feel like you started thinking about being a storyteller, and was that specifically connected to film, or was it more general?

YOUMANS: Initially, my first walk into art came as a painter, actually. I was a painter when I was a kid, and then after that I sort of fell out of love with visual art and then fell in love with acting and performing. At least I thought I was in love with it, you know. Then I realized as time went on that the creative control that I was really, really interested in was not in front of the camera at all. Once I realized that, then I feel like I opened up an entire lane of self expression. I was talking to a friend of mine about it recently, how art has been a therapeutic thing for me my entire life. To a point where it’s always seemed like the best therapy. That’s why I think at the [Sundance Screenwriting] labs, whenever we had those conversations about not separating yourself from your work and not being afraid to see yourself in your work, that was so big. Even before I’d say I was confident in my voice, I was making art. I was making art and drawing ever since I was six, seven years old. Then before that I was always trying to create characters. I used to get naked and wrap a cloth around my body and say I was Tarzan, and then Santa Claus. I’d put on a Santa Claus hat and run around the house and put toys in a bag, bro. I was always a very eccentric kid. I think a lot of that came from isolation early on. I was definitely more isolated than I am now. I think if anything, I’ve sort of slowly sort of grown out of the seeds of my introversion, but that’s still a part of it. How about you, bro, where did you start? I know you have a background in music. How did that all start for you? When did you first sort of pitch your fork into art?

ZEITLIN: I think for me it was always a reality. My mom was actually writing a book about children. My mom and dad wrote this book called City Play—what games kids invent and what worlds they invent when they’re playing in the city. My mom would sit there with a notepad and just let us do whatever we want and let us sort of go. We’d play in this alleyway where all the kids would gather. From that moment, we were inventing stories, turning cardboard boxes into pirate ships. I never remember that changing. I remember when my sister was born…we had a little puppet stage thing. My favorite thing, I’d write these plays with my dad that we would do with hand puppets and stuffed animals, and create these stories for my sister. They were heavy special effects, always. There always had to be a scene where one of the animals ziplined down to the stage. Things were blown up. That was a total continuity between just imagining and storytelling and making film. It was actually a disappointment as I grew up and realized that you had to pick an art form. At some point, you were going to have to apply for college and major in something. These structures were going to come into creativity. For me, there wasn’t any difference between making a haunted house and making a short film. It was all creative and was what I wanted to do on the weekends, and that was just life. I was in a band. I sort of thought for a long time I would sort of focus on music and writing music. I think what led me to film was actually that it was an art form where I could continue basically every single other art form that I love, which was writing music, writing stories, creating characters, directing, photography. It was an art form that I felt like encompassed them all. That’s what really got me to just make the decision that I would be a filmmaker as opposed to anything else.

YOUMANS: Ben, whenever we first met, what were your first thoughts whenever you got that DM that I sent you, man?

ZEITLIN: Whenever anybody sends me anything I try to look at it. A lot of the times it isn’t that great, but I always try to respond to people. When I got the message, it took me a couple days to read it, I remember. I don’t really know how to use Instagram, so I didn’t even really know what direct messages were. Then I think I found it months after you sent it to me, and I was like, “Oh, there’s this other button on the thing.” Then when I looked at it, I was astounded by the cinema of it. What really got me was—it was the cut from the preacher preaching, to him drunk driving in the car and the sermon continuing. I was like, “Wow, that is a bold choice. This is a filmmaker.” The shots were great, the acting was great, obviously all that I could see. I just saw that you were visually fluent in this way that is really rare. At this point I had no idea how young you were. The biggest part of my work outside of making films is I really love supporting filmmakers, and particularly filmmakers in New Orleans. and trying to help them. Also, just on a selfish level, because I just want there to be more filmmakers around. I’m never going to leave New Orleans and I just want to see more New Orleans movies in my life. All those things ran through my head. I was like, this is no question, whatever this dude needs, I’m going to do for him.

YOUMANS: New Orleans, it’s a cultural hotbed, man. That place is always home.

ZEITLIN: And there’s quite a few filmmakers that come from other places and live in New Orleans, but there’s not a lot of directing voices out there like you, that are from the city and have stories to tell that come from that experience that I would never have. Those are films that I’m just dying… I literally just want to watch the movies. All the help is just selfish, man. I just want to see your films.

YOUMANS: What do you think drew you to New Orleans most?

ZEITLIN: I keep on talking about my parents here, but we would go on these trips every year. We would drive somewhere where they knew a folklorist, and we’d go to different cities and experience the culture of the cities. I came to New Orleans when I was probably 12. I just remember a couple specific things. I remember just being art that was being made for its own sake. That’s something I really love about the city. People do all this incredible labor. Between the costumes, everything that happens around Carnival, people make all this stuff. Then they don’t take any pictures and then it gets destroyed, and then no one ever sees it. I don’t think I knew that then, but there was something about that that I really related to. I always want to feel like I’m making art for the sake of art and then not making it for my career or any sort of external success. I do it for its own sake. I think I felt that when I was 12, when I came for the first time. Then when I came down and started making the first short that I made in New Orleans, it was a story about people building a boat out of garbage that they found around.

YOUMANS: The movie’s incredible, Glory at Sea?

ZEITLIN: Yeah. It just started happening. It was crazy. Someone would come in for an audition, we’d tell them about the story, they’d do their audition. One of my great friends, he’s passed away, this guy Jimmy Lee, he drove up with a truck full of stuff and they totally made no sense. Pillars and bowling pins. It was just totally random stuff, and he’d be like, “I think this stuff needs to be on that boat.” I’m curious about the same thing with you. What’s your relationship with the city?

YOUMANS: It’s literally a conversation I have with myself all the time. I feel so much pride to bring stories back to New Orleans, bro, especially with my next one, with Magnolia Bloom, I feel not necessarily indebted, but it’s a prideful sort of debt in a way, where I feel like I have to shine a light back on the city through my perspective, through what I grew up with. I don’t know, man. It’s home, so I also feel like no one except us is really going to shine a light on this city. I feel like it’s kind of our duty to continue to do it. You know what I mean? Maybe you, the Ross brothers, Garret Bradley, anyone who comes to New Orleans is a New Orleanian, no matter if they’re born there or not. I think the city has also given me everything, man. It’s given me all the artists that continue to make a difference in my life. You, John Baptiste, Wendell, all of that came back to New Orleans. It always comes back to New Orleans in a way.

ZEITLIN: Yeah, it’s funny you talk about that. I feel the same. I feel indebted. It’s weird, but not in a bad way. I feel like it’s like I have like a duty. I don’t know how to describe it, but it is that feeling because the city gives you so much. I talk about New Orleans like it’s my wife. It has this personality that’s human almost.

YOUMANS: Dude, that’s so dope, bro. The city will love you forever, bro. I’m about to tear up, straight up, dude. In truth, every story that I think about, it always comes back to New Orleans. No matter where I’m pitching my tent, it always feels like it’s still about home. You went through the screenwriting labs, man. Tell me about what your experience was like with the labs.

ZEITLIN: It was crushing. They just tear you apart, and they tear in the best way. It feels like they take whatever part of you is the artist and they just shatter it. Then you look at it on the floor. Then you can see all the parts of it clearly.

YOUMANS: Then laugh at it.

ZEITLIN: It really taught me how to really look at what the central question I was trying to answer is in myself, and how that related to the story I was trying to tell. That was invaluable. Those were lessons I never got. Sort of similar to you, also. I didn’t go to film school and so I didn’t know… You know a whole lot more than I did when I went to the labs. I was trying not to get caught not knowing what a gaffer was, you know what I mean? For me it was both this incredibly intense and illuminating artistic experience. Then also it was just basic Film 101 for me where I actually learned how a set works and how to be a director on a basic level, so. How about you? What was your take-away?

YOUMANS: I realized how much I was writing a script just for myself, and how much I’m supposed to be writing a script for everyone in the department. The actor should be able to read the script and there should be enough sort of open-ended thing where they can bring their own interpretation and POV to a character. I feel like what they taught me was a lot more craft-oriented, also. Honestly, if you look at a page in one of my scripts, the action lines are 10 lines long. That’s how I’ve always written, but I also realize that I was, in a way, hiding behind camera direction to not face a lot of the problems in my story, bro.

ZEITLIN: I remember having the exact opposite experience. I had not used a screenwriting program. I came to writing scripts from writing songs, essentially, lyrics and stuff and short stories. I actually learned that there, that every line of a script is, you’re just describing your shots. I remember specifically that revelation of ,”Oh, this is just me writing down what I see.”

YOUMANS: They also tore it completely apart and pushed me to ask the same questions that you’re talking about, asking what my legitimate intention is with the piece outside of the idea of the piece. It’s like, “what is my relationship to the piece outside of just me liking the idea of making the piece?” Asking that question was huge. It’s almost akin to a question you have in a relationship. Sometimes we adore people and we really more like the idea of them than the actual substance and interactions with them.

ZEITLIN: Yeah, I believe you. It’s funny. Just the question of, “why do you want to do this?” I remember being so surprised by that question. It’s crazy that you just don’t ask yourself that.

YOUMANS: Dude, yes, and it’s always the hardest question to answer. You feel like you know it in your subconscious, but you have to fucking pull it out. You have to really dig.

ZEITLIN: Yeah, because there’s always a surface level of like, I want to tell this story because it’s going to be awesome. I want to blow this thing up and this is going to be really cool. What’s cool is when you have someone really challenge you to answer that on the deeper level. I’ve been in the bubble of this movie for seven years and people who’ve seen it have been people that I know and that I understand and seeing people come to it raw and hearing those first reactions and what interests them and how they’re interpreting the story, you get a lot. You learn a lot about your own work in this first pass of interviews. It’s actually pretty surprising and pretty fun. You talk about it too much and it starts to repeat itself, but the first time through is always really fascinating for me.

YOUMANS: Yeah, I feel like that’s something that I found with Burning Cane. It’s like I tried to make sure that I didn’t really want to ever repeat myself, but it feels like sometimes a lot of the questions are coming from a similar angle. I made an intention to try to discover new things about it and say new things about it in that way, but I understand what you’re saying. All in all man, I am just really gracious to have you as a friend and you’ve been a mentor and really… I don’t know, just a dope dude since the moment I met you, man. I don’t know, man. I’m proud.

ZEITLIN: Thanks, man. I feel the same. You’re an inspiring dude yourself, man, and I really appreciate our conversations every single time. It’s great to have people in your life that are all in, fully in like you are. Every time we talk I feel like I’ve got to work harder and that’s a good feeling.

YOUMANS: Hey, same here, man.