How Perfect Blue predicted all our social media anxieties

It’s the rebellious cult gem that set the benchmark for a whole new era of anime. Darren Aronofsky bought its remake rights and Madonna included clips in her Drowned World Tour. Twenty years on, one can appreciate just how prophetic this blurred-reality brain-bender was in anticipating the dangers of the Internet.

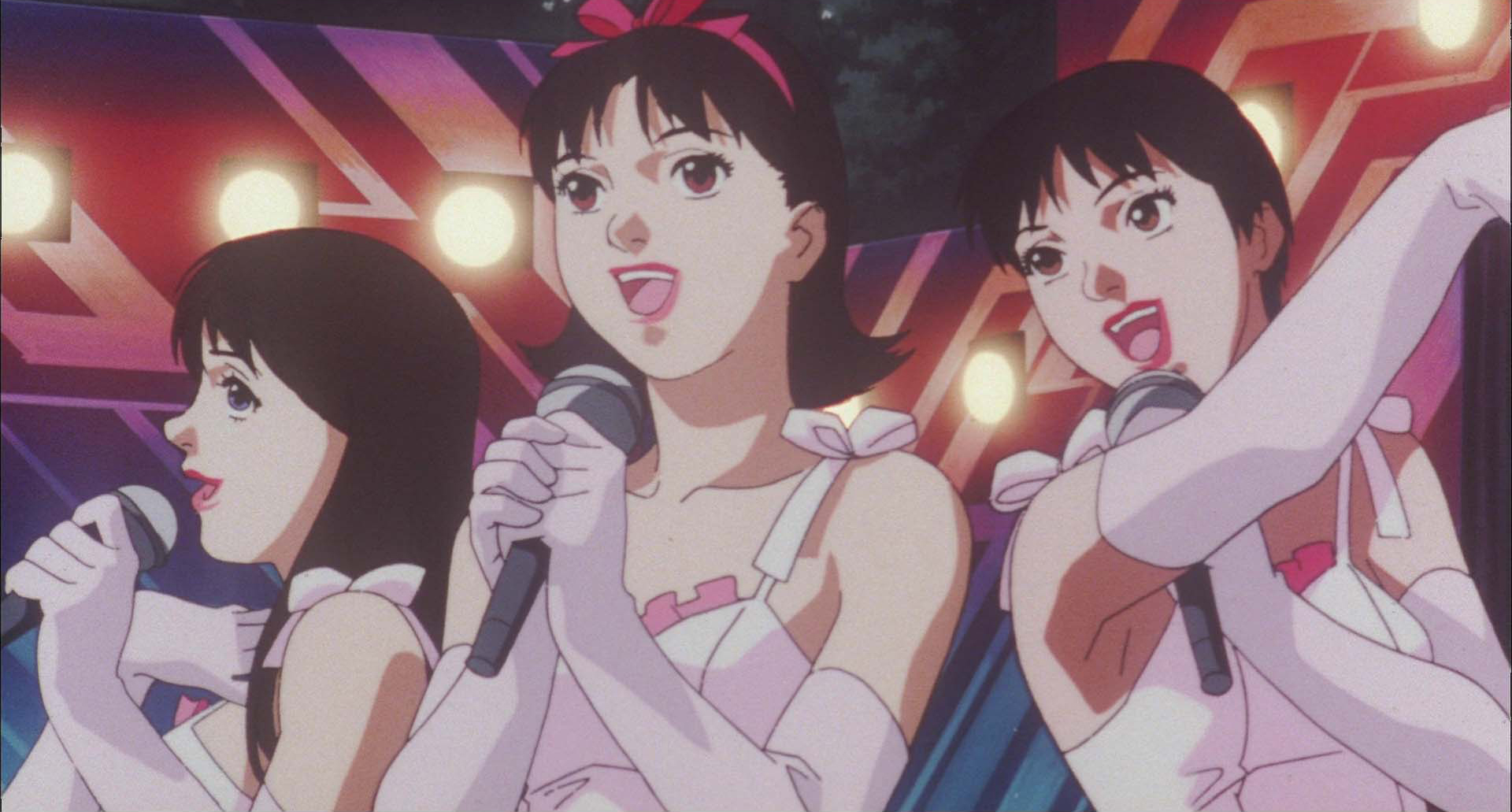

Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue charts the nightmarish downfall of Mima, a chart-topping idol who leaves J-pop trio CHAM! to pursue an acting career, to the dismay of some creepily dedicated fans. When she accepts a part in a controversial crime drama with a rape scene, her life begins to spiral out of control. A stalker site entitled “Mima’s Room” begins documenting her every move, a mysterious doppelgänger torments her with increased frequency and many colleagues turn up dead. This psychological fright fest allows us to experience Mima’s descent into madness from her highly unreliable point of view, as we question where reality ends and delusions begin.

“With Satoshi [Kon], we’d talk about how the scariest thing was being followed but not knowing who or what was following you,” recalls the film’s producer Masao Maruyama, on the occasion of Perfect Blue’s 20th anniversary re-release. “Mima starts out being followed by a man, but part way through, she no longer knows what’s following her anymore. Maybe she’s being followed by herself.”

The biggest tragedy about Perfect Blue is that its celebrated director is no longer around to comment on his exploration of a character living under constant surveillance, suffocated by her multiple identities. Having passed away of pancreatic cancer in 2010, Kon’s modest body of work (four films and one 13-part TV series) nevertheless lives on to inspire generations of filmmakers, including Christopher Nolan and Darren Aronofsky. “I was at a meeting between Christopher Nolan and Satoshi Kon,” remembers Maruyama, “and they’re both extremely talented directors from the same generation. Had Kon still been alive, they would probably have ended up working together on something.”

In fact, Nolan acknowledged Kon’s final film—the dream therapy fantasia Paprika (2006)—as an inspiration for Inception (2010). Aronofsky has paid tribute to Perfect Blue more than once. Numerous online anime shrines point to the Jennifer Connelly scene in Requiem for a Dream (2000) where her character screams into the bathtub, her head submerged in water, as a direct homage to Perfect Blue’s Mima doing the same. And that’s without getting into the contentious Black Swan (2010) comparisons, as there are clear parallels between Mima’s plight and that of Aronofsky’s ballet hopeful (played by Natalie Portman), whose attempts at artistic success and freedom are thwarted as she slowly breaks down, only to find herself stalked by her mirror self.

Kon—who cited John Carpenter and David Lynch as inspirations for the ways in which they probed the porous border zones between waking life and dream worlds, and authenticity and performance—only signed on to Perfect Blue after being granted the freedom to make considerable changes to the script (based on a 1991 novel by Yoshikazu Takeuchi). “In its original incarnation, it was a female protagonist following a male character, but that’s a story you hear a lot in anime, so we decided to change the viewpoint to that of a woman being followed,” Maruyama explains. “And we thought, what if it wasn’t just that, but also the fear that she was not only being tracked by him, but also by herself?”

In many ways, Perfect Blue serves a robust feminist critique of the tired virgin/slut dichotomy and other impossible standards society often holds women to. Mima-the-actress plays the part of a woman being raped. She triggers Perfect Blue’s psycho killer (aptly named Mimaniac) to carry out startling violence, and it’s all to preserve his untarnished fantasy of Mima-the-innocuous-idol at any cost. The repeated threats Mima faces eventually consume her thoughts, as her hallucinated doppelgänger reminds her: “Nobody likes idols with tarnished reputations.” But Maruyama isn’t interested in talking about how Perfect Blue condemns the hardcore fan club culture driving Japan’s idol industry or the ways in which it can infantilize and objectify women. “I don’t really know, because Perfect Blue used an idol as a character,” he counters. “To be honest, I’m not interested in her as an idol. I’m interested in her as a character, in her life as a person.”

As a cautionary tale about the pitfalls of fame, the game of cat and mouse played out by Mima and Mimaniac could potentially have drawn from a whole spectrum of real-life incidents. Chief among these was Björk’s infamous stalker Ricardo López, who in 1996 attempted to kill the Icelandic singer in a failed murder-suicide scheme around the time Perfect Blue was in production. Reports suggested López couldn’t wrap his head around the fact that the object of his unrealistic adoration was not a fantasized fabrication but a flesh-and-blood human. Maruyama says the team wasn’t aware of Björk’s ordeal at the time. “Of course, it sounds like the themes of our film were echoed in reality—the real universe versus your projected image. The theme of another self is something Kon explored again in Millennium Actress (2001) and Paprika (2006). This idea of an unknown self that goes beyond the image we project. It’s interesting how it could appear as though art imitated life here, but we didn’t base Mima’s plight on any real-life incidents.”

Stalker storyline aside, Perfect Blue’s eerie exploration of people peering into the lives of others and hence skewing their sense of self couldn’t be more on the nose in this age of Instagram influencers and envy-inducing Facebook feeds. In certain respects, the film makes its 1997 release date abundantly clear—Mima is initially threatened by way of a fax (!), and the perplexed pop star describes the internet to her agent as, “Ah, that thing that’s been popular lately!” But Perfect Blue’s overarching theme of blurred public versus private selves is all the more chilling when you consider such predicaments are no longer limited to celebrities. We all run the risk of assessing someone strictly by way of their carefully curated online identities. Which begs the question: would Maruyama consider updating Perfect Blue for the times? “I couldn’t do it without [Kon],” he says, thereby ruling out the possibility of a sequel. “I did talk to him about doing something at some point, prior to his passing, but unfortunately we weren’t able to.”

PERFECT BLUE WILL BE OUT IN THEATERS ACROSS THE U.K. ON OCTOBER 31, 2017.