Caught on Tape: Paul H-O on Cindy Sherman

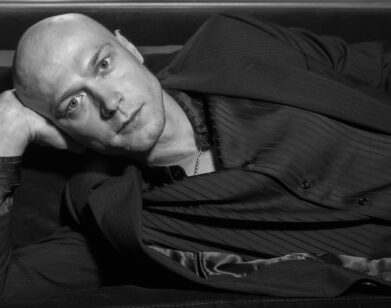

Paul H-O and Cindy Sherman

A few years ago, art-world videographer Paul H-O dated a famous artist. Now he’s made a movie about it. The irreverent protagonist and co-director (with Tom Donahue) of the new documentary Guest of Cindy Sherman tells Interview why his ex is “not comfortable” with his film, and why he’s been called both too sensitive and a “sexist bastard.”

DARRELL HARTMAN: How does Cindy Sherman feel about your movie?

PAUL H-O: She was very supportive of the film when we were together, but she had more bouts of discomfort as time went on and it started to shape itself into something. She realized at a certain point that the film was basically beyond her control—not just Cindy, but the people who handle Cindy’s career. They were not comfortable with this project because they saw it being potentially destructive to the image they’d spent 20 years creating. When you’re dealing with the gallery system and the museum system it’s all about how an artist is portrayed, and why it’s so terribly serious, what these people do, is because it actually doesn’t matter at all to the outside world. It has no effect on what the price of bacon is going to be. The ones that don’t take it seriously are really the artists. They see it in much better perspective—until they become part of the system.

DH: What exactly do you mean by that?

PH: Absorbed into what we would call management part of the art world. Then it’s one big happy family.

DH: How can you tell when an artist has crossed over?

PH: Just about anybody that moves into the Gagosian Gallery, I would say, has sold out.

DH: Did you ever think this film could damage Cindy’s career?

PH: Oh, absolutely not. We see it as a historic document. There is no other source like it. I have Cindy in the studio working, which not even her assistants were privy to. We were out in Sag Harbor and she was working in the attic and she just, I don’t know, just one day thought it was okay. Out of the whole film, that is the most historically poignant moment, to watch Cindy at work.

DH: At one point in the film someone says, “She doesn’t break a sweat.” Is that she way Cindy Sherman makes art, that she just kind of does it?

PH: She does just kind of do it, as a savant. She’s not a mad artist in the laboratory. A show is announced with her name on it, and then six or seven months before, she’ll say, “I think I better start working on this show.” She’s incredibly organized, and also very relaxed. It’s an everyday thing, but not on the weekend. She’s a consummate pro—a lot of the top artists I’ve spent time with are. They know how to get their work together in time for the catalogue. These guys operate like surgeons.

DH: I think a lot of the best creative types work that way.

PH: Stravinsky used to get up every day and write music. And at 11 he’d have tea or something like that, and then have people over for lunch and work a little bit in the afternoon.

DH: On the other hand, being too comfortable can work against you.

PH: Philip Guston is such a revered figure in art because he did something that was unbelievably gutsy: He changed his work when he was doing just fine. Artists would be much better off if they were free to take those kinds of chances. Making great art is not about doing the same thing over and over and over again, and I will criticize Chuck Close and Cindy, to some degree, because okay, we get it. We know what you’re going to do next. You’ve got the resources to do whatever you want. Why do you keep doing the same thing?

DH: You got to know a lot of artists, including Cindy Sherman and Chuck Close—through “Gallery Beat,” your public access TV show. Who else?

PH: We had Brice Marden, Andres Serrano. We followed Cecily Brown, a whole process piece, from the beginning of her first show at Deitch Projects to her first show at Larry Gagosian. Most of the name-brand artists who were TV-friendly showed up on Gallery Beat.

DH: Any who were not TV-friendly?

PH: Alex Katz, I would say he’s not TV-friendly. Chuck Close was completely TV-friendly-very affable. But as far as I was concerned, he was overexposed. I loved working with artists like Vanessa Beecroft, Sean Landers, Kevin Landers, Fred Tomaselli, Fred Wilson.

DH: But when you’re at that Vanessa Beecroft opening in the film, you turn to the camera and say something like, “Can anybody tell me what the hell is going on here?”

PH: Well, art’s pretty hilarious. I mean, come on. That Russian who locks himself in a cage for a month, naked? What’s not to laugh at?

DH: Julian Schnabel didn’t seem to appreciate it. He calls your show idiotic.

PH: I know, pure gold. I love Julian very much, actually, and I think he’s a pretty good artist. He might be who he is and he may not have any great love for me, but without characters like that, what do you have? It’s tension that makes a good story. If it’s all a big love-fest, it’s just boring. That’s why we have train wrecks in the film, because those are the moments people remember. They remember when we get kicked out of Pace Wildenstein. And Dia was totally reliable. If we needed a little action, we would go to Dia and they’d kick us out and we’d have some more material.

DH: And they probably didn’t bounce you just because you had a camera.

PH: We question what’s being placed in front of us. We do not just accept it as being you know, like, whatever’s in the press release. A press release may be helpful, but I mean, talk about bullshit!

DH: Have people criticized you for this movie?

PH: Sure. Pretty much whatever reaction you can come up with—from being called a sexist bastard to [being called] a too-sensitive male.

DH: You subject yourself to a pretty scathing critique when you tell Kelly Jones and Bronywn Carlton, the WFMU radio hosts, that you feel overshadowed by your girlfriend. They basically tell you to get over yourself.

PH: I listened to their show fanatically. I knew who I was dealing with. But I never dreamed that they would pick up this subject and run with it the way they did. It was a magic moment.

DH: They think that men have a problem dating successful women.

PH-O: Don’t you think they do?

DH: Sure. Men are men.

PH: What are we here for? Really, whatever it is we do is pretty much obsolete. We build all the stuff that wrecks everything. Women have a completely different point of view. And when you live in New York, it’s pretty common for a woman to make more money than you. Almost all the girls I know make more money than I do! And my male friends—I don’t know what the percentages are, but the women are the major breadwinners. We’re drones.

DH: To a lot of people, that’s kind of pathetic.

PH: They say that rich men make better lovers, for sure.

DH: Really? I haven’t heard that.

PH: I just made it up. But that’s always the excuse—”Well, yeah, he’s short and fat but man, he’s really good in bed.” [Laughs.] But what am I going to do? I’m in the business I’m in because I like it. It’s just not a big rolling-in-money situation. It can be, and you always hope you’re going to hit it. But the whole point is that you’re doing the work you’re passionate about.

DH: Did you have any reservations about making a film that’s so personal?

PH: At that moment I was really used to journalizing my life. It was a very natural thing for me to say, “Oh, at this point I’m sick; at this point, I’m going to move; at this point, I have a new girlfriend; at this point, I’m broken-hearted and depressed and want to kill myself.” But I mean, hell, it’s a highly edited piece of work. I don’t say everything I think.

DH: But everything you did say is now out there, forever.

PH: Those are moments that never come back, and you’ll be far more critical about them during the immediate period that you’ve done them. But boy, give it time—five years, ten years, fifteen years—and you and everyone will look back on it and go, “Hey, not so bad.” People’s opinions about themselves evolve-and definitely for the better. Believe me, Cindy’s going to look back on this 20 years from now see a different document.

Guest of Cindy Sherman comes out Friday in New York and Santa Fe.